Impacts at Home

Reverting to the question of why we should care about two random prisons sixty miles from Easton is necessary if we want to avoid such injustice in our hometown. While many are unaware, the Northampton County Prison is located merely four minutes away from Lafayette College and houses nearly 1000 inmates. At 145 years old, the prison is not only one of the oldest in the state, but the one of the costliest to manage at ~$107 per inmate per day (Shortell, 2016). It goes without saying that, even after living at Lafayette for four years and having explored the downtown area more times than I could even begin to remember, the fact that myself and the water justice group was unaware of the Northampton County Prison speaks for itself. Like all prisons, it is surrounded by a chain-link, barbed wire fence that might as well be compared to another world. Although no reports have come to surface, the Northampton County Prison is as much at risk as these other prisons discussed.

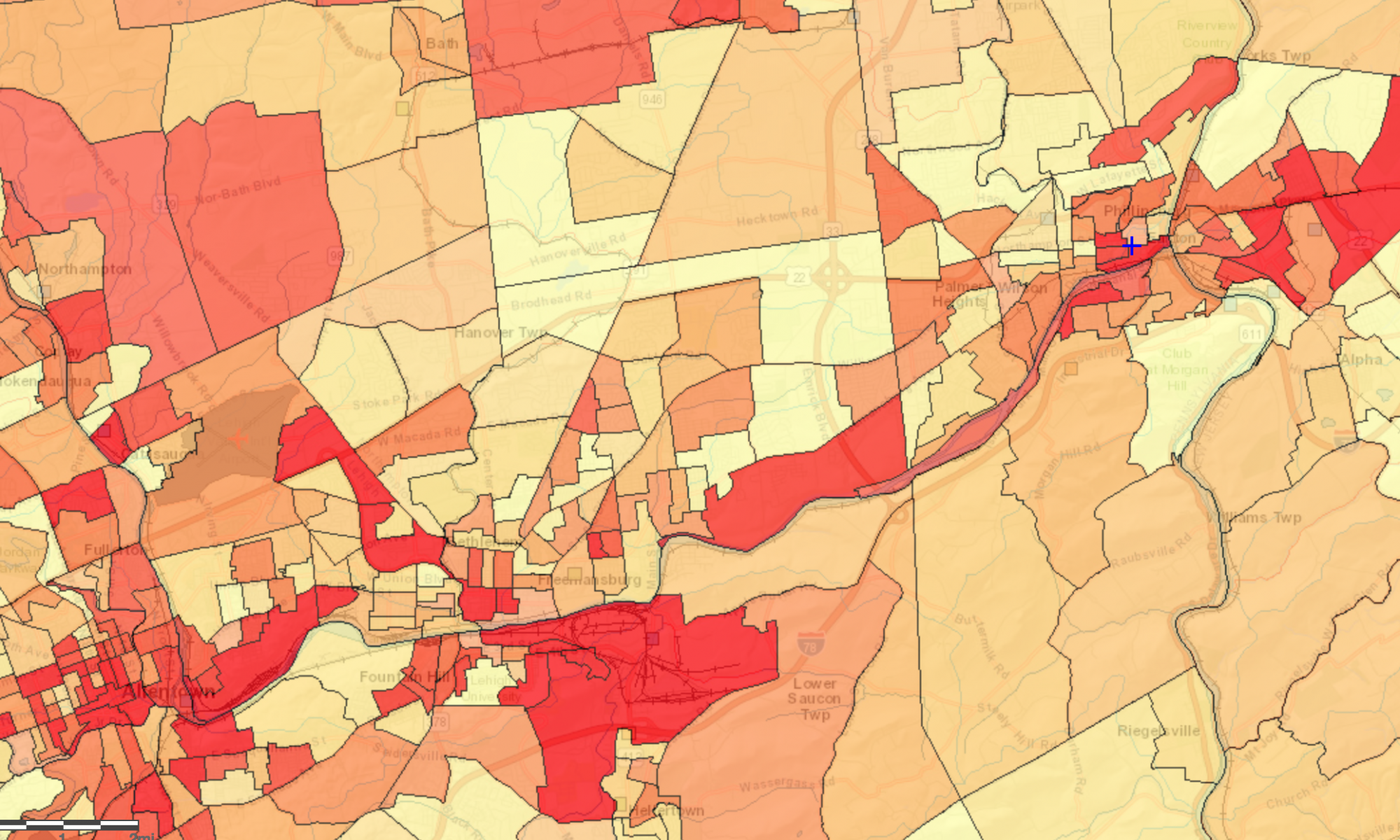

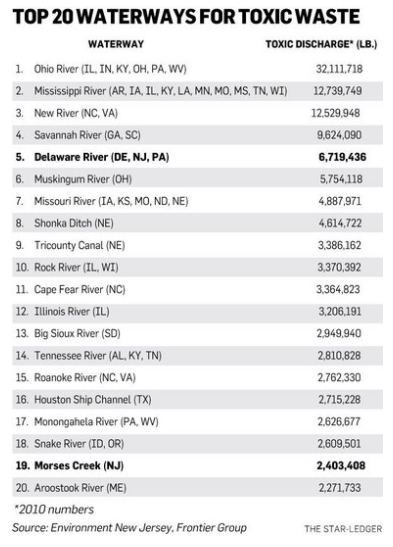

The prison, as does much of Easton, receives their water from the Easton Suburban Water Authority. The ESWA’s main source of water is the Delaware River, coupled with the Lehigh River as a major tributary. Although the Lehigh River was once considered an environmental waste dump from once being the private corridor of the Lehigh Coal Company, due to government and public activism, cleaning efforts have been very effective (Darragh, 2010). In fact, Wildlands Conservancy even nominated the Lehigh River for Pennsylvania’s 2016 river of the year. However, companies along the Lehigh River, such as the Northampton Generating Plant, still practice the dumping of waste and coal ash into the river. Similar to the John B, Rich Memorial Power Station, the Northampton Generating Plant is a co-generation plant fueled by anthracite waste coal. In fact, their offsite waste disposal of over 1,800 pounds per year trumps John B. Rich’s—however, they are similar in their historic violations of coal ash dumping into rivers (See Visual 6 and Visual 7). Thus, it is evident that in spite of the tremendous progress the Lehigh River has made in clean up efforts, dumping is still a very prevalent and serious problem. Likewise, the Delaware River currently ranks fifth in the nation for toxic dumping at 6.7 million pounds per year. In fact, according to Environment New Jersey, a non-profit environmental activist group, the majority of this pollution comes from “DuPont Chambers Works in Salem County, which is legally permitted to emit 5.3 million pounds of effluent into the watershed.” Second on the list was ConocoPhillips’ Bayway Refinery, who is reportedly allowed to dump 2.4 million pounds of toxic chemicals into a nearby creek (Augenstein, 2012). The problem is not the companies, who, although raise an ethical question of dumping in the tributaries of the Delaware River, are simply abiding by the provisions granted to them. Put simply in the words of Tracy Carluccio, the deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, “the problem is that government agencies allow these discharges to continue by issuing permits to pollute, a perverse interpretation of the Clean Water Act” (Augenstein 2012).

While the prison has reported no issues to date, we argue that because of the old infrastructure, high cost per inmate, and persistent pollution in the Delaware River, an injustice such as those in SCI Frackville or Mahanoy may very feasibly arise at Northampton. The most interesting piece here is obviously the rising costs per inmate—as ensuring appropriate water a nd health standards for inmates in the event of water contamination would inarguably not take precedent if food/living costs are already some of the highest in the state. In addition, with the new Trump presidency, streams and river dumping will likely become more lenient for companies and initiatives, such as what we have seen with the approval of the PennEast Pipeline, will further pollute such waterways (Please visit the Energy Justice page for further details). As members of the LEJI, we must remain vigilant to ensure that if community water issues do arise, the inmates are treated just as every other citizen of Easton.

nd health standards for inmates in the event of water contamination would inarguably not take precedent if food/living costs are already some of the highest in the state. In addition, with the new Trump presidency, streams and river dumping will likely become more lenient for companies and initiatives, such as what we have seen with the approval of the PennEast Pipeline, will further pollute such waterways (Please visit the Energy Justice page for further details). As members of the LEJI, we must remain vigilant to ensure that if community water issues do arise, the inmates are treated just as every other citizen of Easton.