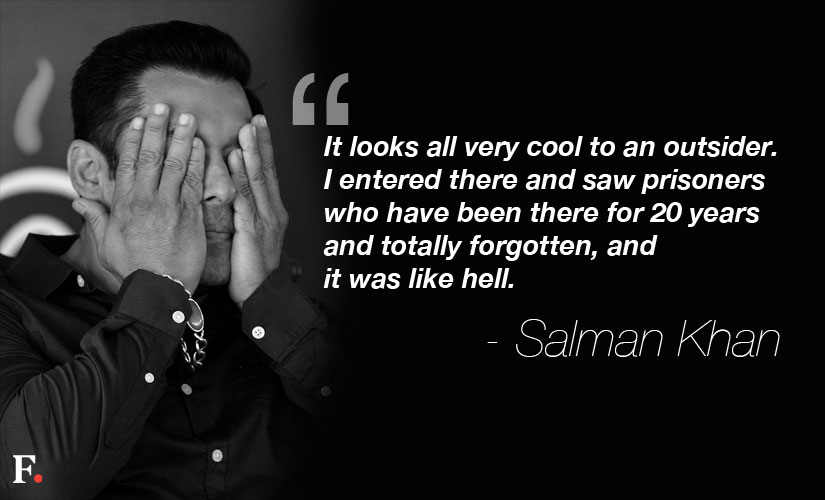

Where do we go from here? When studying issues of environmental injustice, marginalized groups are typically considered the low-income communities or ethnic minorities. This pattern is prevalent based on fundamental elements of institutional racism, which allows the voices and rights of minority communities to be easily overlooked. However, another significant population, about 2.2 million people in the United States alone, is also significantly neglected and often forgotten about in discussions of injustice. This is the inmate community, located in prisons across the country. The negative connotations associated with prisoners are often challenging to overlook; however, in order to holistically evaluate issues of maltreatment and oppression, we must change our perspective to acknowledge prisoner negligence as a human rights issue rather than an inmate rights one.

When studying issues of environmental injustice, marginalized groups are typically considered the low-income communities or ethnic minorities. This pattern is prevalent based on fundamental elements of institutional racism, which allows the voices and rights of minority communities to be easily overlooked. However, another significant population, about 2.2 million people in the United States alone, is also significantly neglected and often forgotten about in discussions of injustice. This is the inmate community, located in prisons across the country. The negative connotations associated with prisoners are often challenging to overlook; however, in order to holistically evaluate issues of maltreatment and oppression, we must change our perspective to acknowledge prisoner negligence as a human rights issue rather than an inmate rights one.

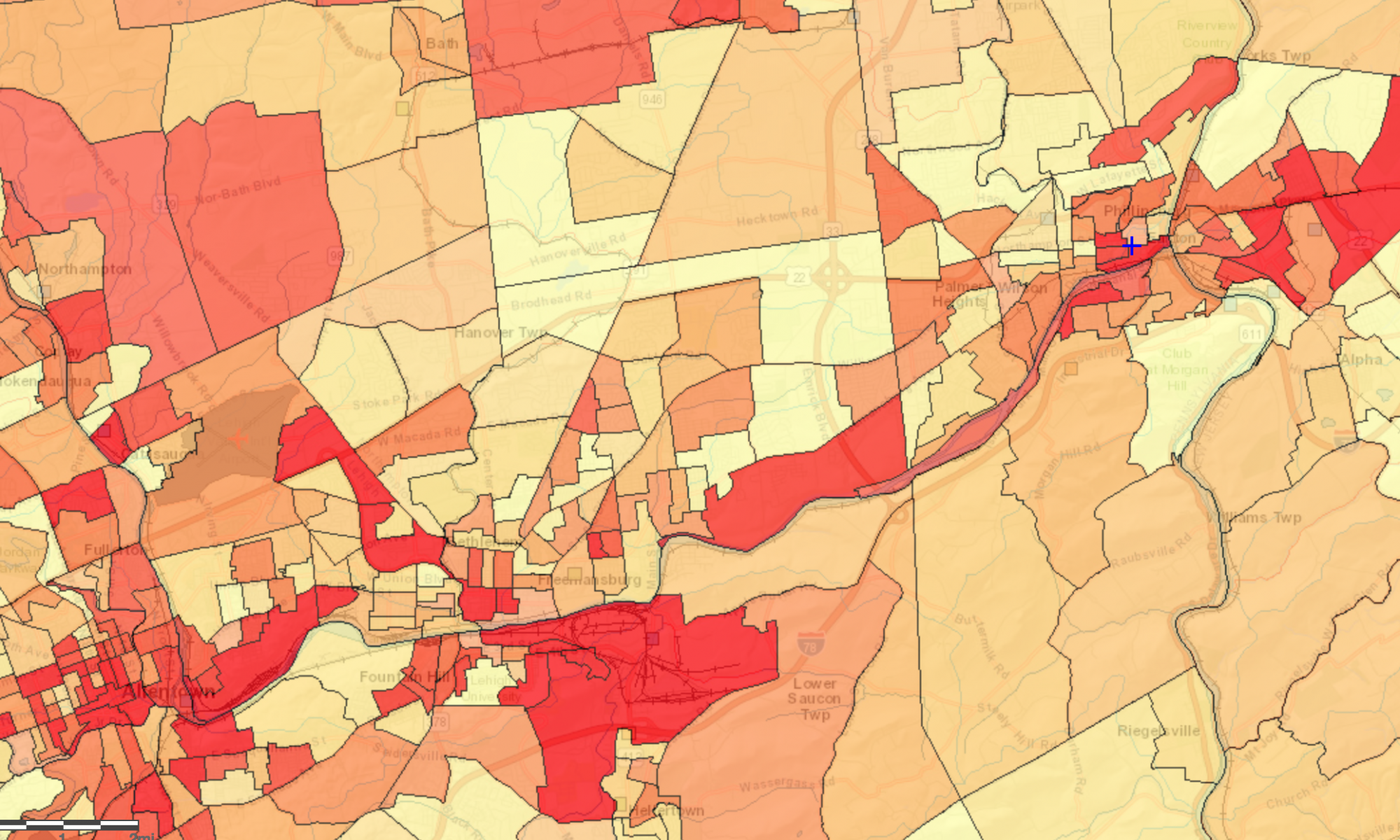

After studying the injustice occurring in State Correctional Institutions Frackville and Mahanoy, we have found a plethora of potential future research to be done. A variety of cases pertaining to inmate mistreatment exist, although they often relate to abuse on behalf of prison staff. However, as the state of the environment deteriorates due to pollution, it is likely that more environment related issues will begin to percolate into prisons, severely impacting the lives of prisoners. For example, as the Penneast Pi peline crosses various tributaries of the Delaware River, a main source of water for the local Northampton prison and Easton in general. As previously discussed, the construction of the pipeline will inarguably contribute more to the already 6.7 million pounds of pollution dumped into the Delaware River each year. Collaboration with the Energy Justice team could be effective in not only helping to prevent this possibility, but also working towards efforts to ameliorate the potential outcomes. For further discussions of this potential, see ‘Why We Should Care: Action in Easton’ and visit the research on the implications of the PennEast Pipeline conducted by the Energy Justice team.

peline crosses various tributaries of the Delaware River, a main source of water for the local Northampton prison and Easton in general. As previously discussed, the construction of the pipeline will inarguably contribute more to the already 6.7 million pounds of pollution dumped into the Delaware River each year. Collaboration with the Energy Justice team could be effective in not only helping to prevent this possibility, but also working towards efforts to ameliorate the potential outcomes. For further discussions of this potential, see ‘Why We Should Care: Action in Easton’ and visit the research on the implications of the PennEast Pipeline conducted by the Energy Justice team.

Here are some of the research questions we propose for future inquiry:

- Are there other United States prisons facing similar issues?

- For issues that have already been reported to the public, a simple web search for issues of water contamination or human rights infractions in prisons would provide the researcher with a wide array of cases.

- As we are doing now, identifying similar warning signs across cases is crucial to preventing future injustices. This also yields the possibility of pairing up with or delegating a team to analyze different aspects of infrastructure justice.

- By looking at the aging infrastructure of prisons across the country, both in respect to dilapidated prisons and the piping networks, research teams may be able to deduce certain water injustices before the issue becomes severe.

- Do prisons with greater amounts of ethnic minorities have a higher number of injustice issues compared prisons that are mainly white/upper class?

- By researching prison demographics and comparing the results, we predict a researcher would find that upper class prisons are more updated, cater more to their inmates, and do not allow prisoners to suffer at the hands of environmental injustices.

- In addition, we also predict that depending on the type of security prison (e.g. medium versus. maximum), the injustices would be more prevalent across higher security institution. The more these inmates are cut off from society, the more marginalized they will be.

- Further, and in connecting this topic to class discussions, this research also raises questions of why some companies choose to build their industrial plants near prisons in the first place. We hypothesize that similar to early cases of environmental justice we have studied, such as in Chester or Kettleman City, polluting industrial plants follow the path of least resistance. As such, an economics sector of the LEJI can aid the water justice team by evaluating the issue from the infringing company’s side in regard to costs and benefits of plant location.

- How is the public informed on issues that happen inside prison walls? Could there be more cases that have yet to be reported?

- By interviewing prison officials or even prisoners themselves, researchers could gain information not made visible to the public. Often, prisoners are advised to not disclose certain happenings within the city walls due to threats of poor treatment. However, with enough research concerning potential environmental injustices within prison walls (e.g. if the prison is built near polluted water systems or heavily polluting companies), one could gain enough traction to put serious pressure on the prisons to disclose the actuality of inmate’s living conditions and amenities to the public.

- Likewise, utilizing the prisoners families and friends by bringing them into the conversation regarding the potential inequitable treatment toward inmates can help gain a community backing that the majority of prison injustice cases lack. No one group could ever possess enough clout to put significant pressure on decision-makers/local officials; however, as we have seen in numerous environmental justices cases, grassroots coalitions and the banding together of communities has been the most beneficial method of implementing and igniting change.

Although some of these questions involve more pervasive efforts than others, finding answers to these questions is imperative in beginning to address marginalized lives of prisoners. It is feasible that as these issues become more pronounced within the media, efforts will be made to address questions such as these. However, until then, it is likely that dedicated students and researchers with a passion for remediating critical issues of inequity will lead the struggle to publicize and improve upon prison injustice.