What’s the issue?

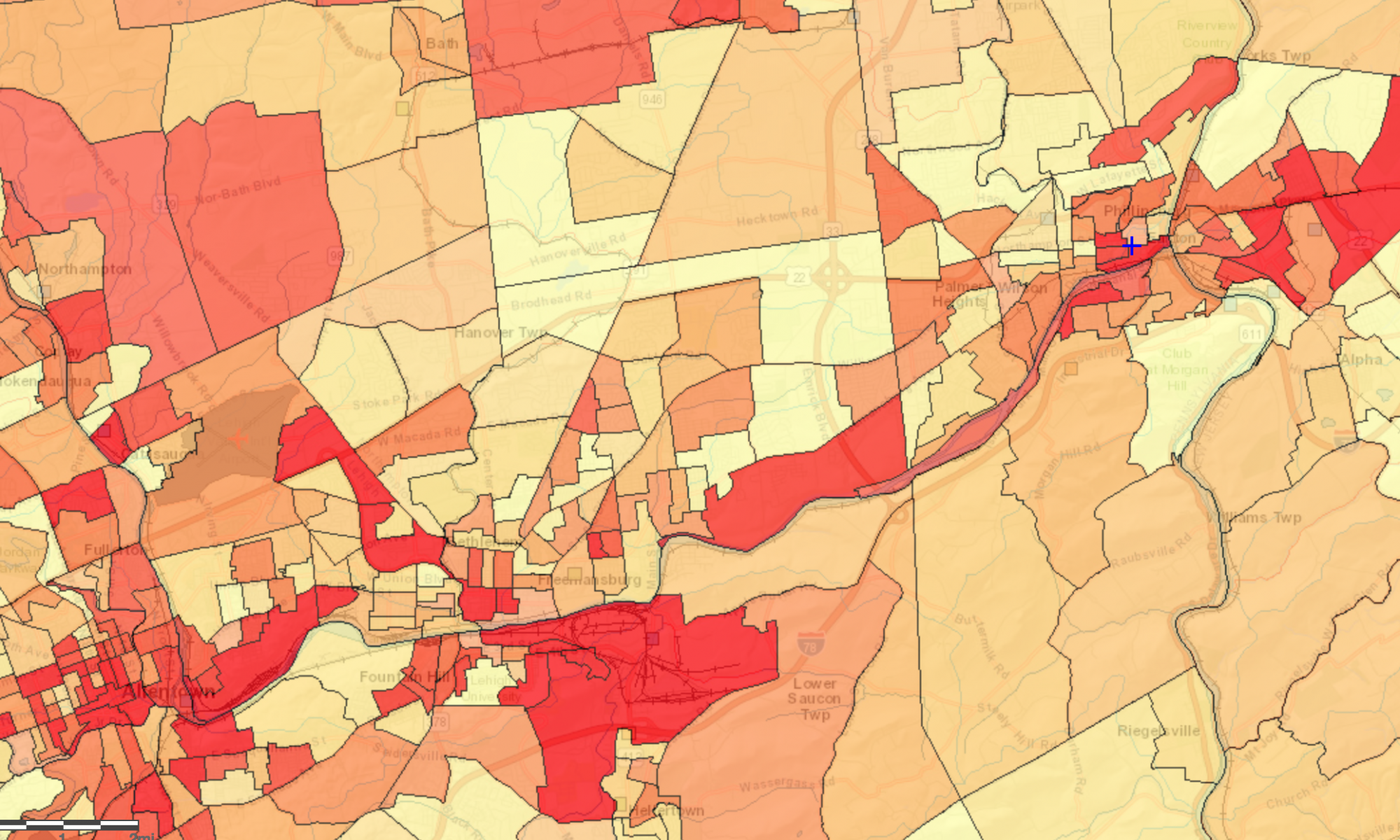

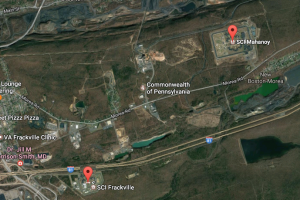

Synopsis: Located approximately an hour and fifteen minutes west of Easton (See Visual 1), the State Correctional Institutions Frackville and Mahanoy in Frackville, PA have been distributing brown/odorous water to their inmates for over two years, while guards and officials receive bottled water. An additional layer of the issue revolves around that fact over 2,500 of the combined 3,700 inmates have Hepatitis C and cannot appropriately follow medical procedures in regard to their necessary water consumption. With no conclusive causal evidence, we project that tributaries of the prison’s water system, the Schuylkill County Municipal Authority, are being contaminated by acid mine drainage from both abandoned mines and the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station (owned by Gilberton Power) situated next to the institutions. This complex case undeniably raises questions regarding distributive, procedural, and recognitional justice; however, it also relates to the broader question if similar issues of discrimination are happening right here in Easton. Considering the Northampton County Prison’s aging infrastructure, rising costs per inmate, and proximity to the polluted Lehigh and Delaware Rivers, the issues at SCI Frackville and Mahanoy pose a serious inquiry into the potentiality of such injustice merely five minutes away from Lafayette College.

Synopsis: Located approximately an hour and fifteen minutes west of Easton (See Visual 1), the State Correctional Institutions Frackville and Mahanoy in Frackville, PA have been distributing brown/odorous water to their inmates for over two years, while guards and officials receive bottled water. An additional layer of the issue revolves around that fact over 2,500 of the combined 3,700 inmates have Hepatitis C and cannot appropriately follow medical procedures in regard to their necessary water consumption. With no conclusive causal evidence, we project that tributaries of the prison’s water system, the Schuylkill County Municipal Authority, are being contaminated by acid mine drainage from both abandoned mines and the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station (owned by Gilberton Power) situated next to the institutions. This complex case undeniably raises questions regarding distributive, procedural, and recognitional justice; however, it also relates to the broader question if similar issues of discrimination are happening right here in Easton. Considering the Northampton County Prison’s aging infrastructure, rising costs per inmate, and proximity to the polluted Lehigh and Delaware Rivers, the issues at SCI Frackville and Mahanoy pose a serious inquiry into the potentiality of such injustice merely five minutes away from Lafayette College.

Why care about prisoners?

As you explore th e LEJI website, you will come across fascinating inquiries into issues of Climate Justice, Food Justice, and Energy Justice right here at home in Easton, PA. As such, you may be asking yourself: “Why would I care about two prisons in a town I’ve never heard of? Why care about those in prison anyway—they did this to themselves.” These questions are irrefutably valid. However, for a moment, imagine if a close friend or relative made a mistake in life that resulted in the imprisonment of 5 years. Each month, you visit him or her and they tell you things have been okay, except for the fact that the prison is giving them brown water that smells like sulfur. Would you care yet? Following, that person proceeds to tell you that he or she has contracted Hepatitis C—a disease that creates tiny scars in the liver that impedes liver function and greatly increases the chances for liver cancer. Your relative tells you that he or she refuses to drink the water and either remains thirsty or drinks soda even though they know it is further damaging to their liver. At this point, it is likely you would be outraged and strongly voice your concerns to the prisons, state, and maybe even federal government. This is exactly what people are doing and experiencing…and no one

e LEJI website, you will come across fascinating inquiries into issues of Climate Justice, Food Justice, and Energy Justice right here at home in Easton, PA. As such, you may be asking yourself: “Why would I care about two prisons in a town I’ve never heard of? Why care about those in prison anyway—they did this to themselves.” These questions are irrefutably valid. However, for a moment, imagine if a close friend or relative made a mistake in life that resulted in the imprisonment of 5 years. Each month, you visit him or her and they tell you things have been okay, except for the fact that the prison is giving them brown water that smells like sulfur. Would you care yet? Following, that person proceeds to tell you that he or she has contracted Hepatitis C—a disease that creates tiny scars in the liver that impedes liver function and greatly increases the chances for liver cancer. Your relative tells you that he or she refuses to drink the water and either remains thirsty or drinks soda even though they know it is further damaging to their liver. At this point, it is likely you would be outraged and strongly voice your concerns to the prisons, state, and maybe even federal government. This is exactly what people are doing and experiencing…and no one has been listening. Thus, while proceeding, I ask that you view this case not through an objective lens of one of two worlds, inmates and people, but that you put yourself in the shoes of the families of these inmates, and understand that serving time does not constitute the reclamation of a basic human right.

has been listening. Thus, while proceeding, I ask that you view this case not through an objective lens of one of two worlds, inmates and people, but that you put yourself in the shoes of the families of these inmates, and understand that serving time does not constitute the reclamation of a basic human right.

Prisoners make up approximately 2.3 million people of the U.S. population, 50,000 of which are residents in Pennsylvania. Through the ‘objective lens’ mentioned above, we in everyday populace do not view inmates as part of society. The chain link, often barbed wired fences confining institution sites are often representative of this. Even when we think of the conventionally accepted definition of Environmental Justice as, “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies”, prisoners fail to adequately fit into this description. Often, we focus on impoverished, minority, or marginalized communities and fail to recognize the fact that putting a person in jail does not take away their humanity. It is without question that an individual in jail does not have all of the rights as a person not in jail. On the most basic level, the right to vote. People in prison and on parole or probation cannot vote in elections despite the 15th Amendment. However,  a right to vote, aside from the question of human dignity, does not hinder one’s ability to live or function. Those in SCI Frackville and Mahanoy aren’t being denied water, but they are being denied clean water. Is there a law against this? Absolutely. The Standard of Treatment of Prisoners section a. of Standard 23: Physical Plant and Environmental Conditions, states, “The physical plant of a correctional facility should allow unrestricted access for prisoners to potable drinking water and to adequate, clean, reasonably private, and functioning toilets and washbasin.” The key word being potable. So, if there is a clear violation of a law, and prisoners have used the right to complain about such distribution of water, then the obvious question is why have no actions been taken? Prisoners are people, and despite any past actions that they are serving their time for, they deserve the right to clean water.

a right to vote, aside from the question of human dignity, does not hinder one’s ability to live or function. Those in SCI Frackville and Mahanoy aren’t being denied water, but they are being denied clean water. Is there a law against this? Absolutely. The Standard of Treatment of Prisoners section a. of Standard 23: Physical Plant and Environmental Conditions, states, “The physical plant of a correctional facility should allow unrestricted access for prisoners to potable drinking water and to adequate, clean, reasonably private, and functioning toilets and washbasin.” The key word being potable. So, if there is a clear violation of a law, and prisoners have used the right to complain about such distribution of water, then the obvious question is why have no actions been taken? Prisoners are people, and despite any past actions that they are serving their time for, they deserve the right to clean water.

The Issue in Frackville

Beginning in 2015, an inmate by the name of Mumia Abu-Jamal, reported that SCI Mahanoy was distributing brown and sulfuric smelling water to the inmates. A few months later following the complaint, inmates at SCI Frackville, located five minutes away from SCI Mahanoy, began reporting similar instances. Inmates at both locations only have the opportunity to

buy bottled water in visitation rooms; however, guards and officials have cases available for them at all times in their dining room. Bryant Arroyo, a prisoner at SCI Frackville, claims that when the water is not brown, it is often foamy and chemically scented. While Bryant has contacted the Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvanian Department of Environmental Protection, he believes the officials that came to test did not test the water ‘on the block’ (an area where the majority of the cells are), but rather in areas of the prison where the water is somewhat cleaner (Ross, 2017). As previously mentioned, 2,500 of the 3,700 inmates between the two prisons have Hepatitis C and require a certain amount of water to drink per day. However, many of them resort to buying sugary Coca Cola or Juices from vending machines because of the lack of potable water. According to Amy Hamaker of Livestrong.com, “People with hepatitis C have a higher risk of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes because the virus affects how the liver processes sugar and fats. Eating foods with large amounts of sugar—such as desserts, full-calorie sodas and candy—can further tax the liver’s ability to manage sugar and fat metabolism and contribute to

the development of diabetes or prediabetes. These conditions can increase the rate of hepatitis C-related liver damage.” For a stint of four months in 2016, guards were distributing bottled water to the inmates—yet suddenly stopped because of the increasing expense. To date, advocates have framed the issue around Mumia Abu-Jamal in an attempt to make the issue a human right, as opposed to a right for the incarcerated.

Who is to Blame?

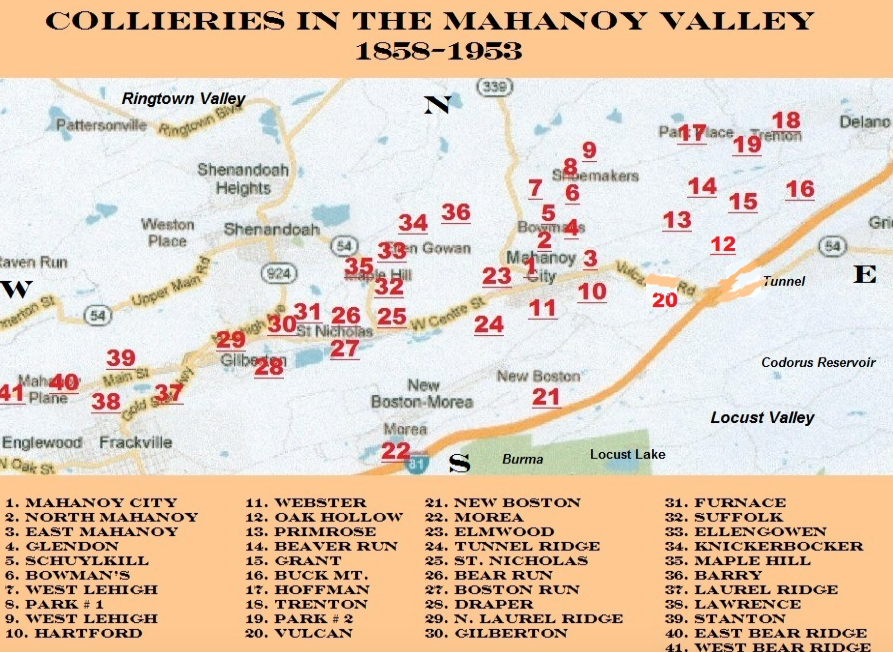

Granted the issue has only been observed and reported on for the past couple of years, no concrete reason has been determined to be the cause of the contaminated water at SCI Frackville and Mahanoy. However, based on our research, we deduce that the issue stems from either Acid Mine Drainage from abandoned anthracite coal mines in the area, or the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station’s dumping of coal ash into tributaries of the Schuylkill River. During the peak years of mining in Pennsylvania between the middle 19th and 20th centuries, the Mahanoy Valley was booming with over 40 anthracite coal collieries (Shown Below).

In the modern day, SCI Frackville and Mahanoy are now situated amongst these inactive coal mines, and may be suffering at the hands of acid mine drainage. Acid mine drainage, or AMD, refers to a process when iron sulfide, or pyrite, is exposed from mining practices, interacts with oxygen, and forms hydrogen sulfide. As rainwater seeps into the ground of these abandoned mines and interacts with the sulfide bearing materials, the run off brings acidic water into the ground that can further dissolve heavy metals into drinking water (See Visual 2). As such, streams and waterways become contaminated

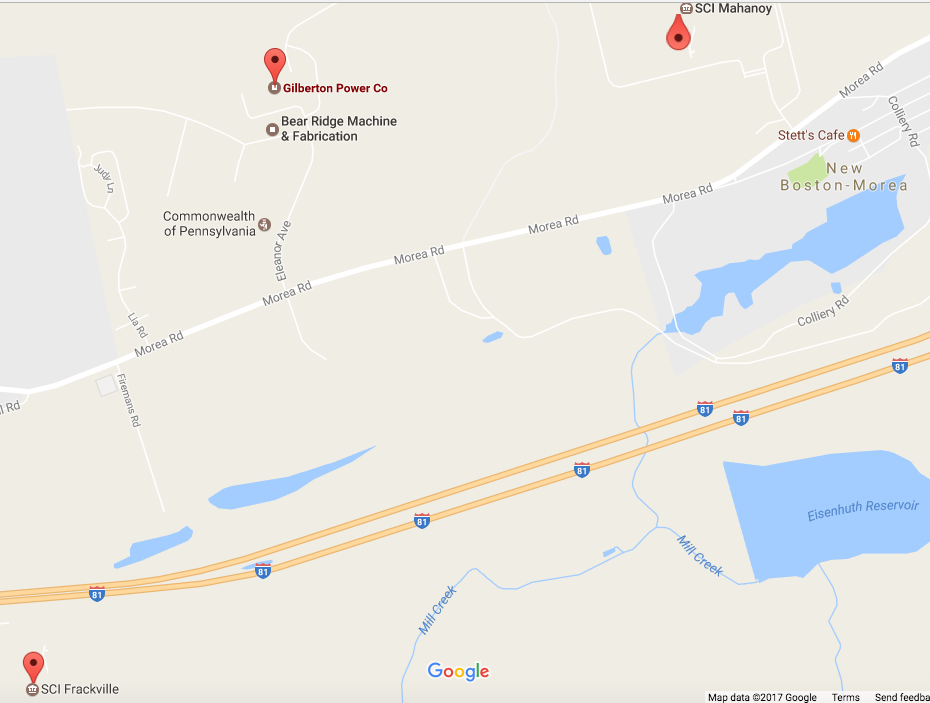

and display an orange/yellow color from the amount of heavy metals in them (pictured right). Both the Frackville and Mahanoy institutions use the Schuylkill County Municipal Authority water system (See Visual 3). We argue that because the Eisenhuth, Kauffman, Mt. Laurel Reservoirs of the SCMA water system are also situated on these historic coal mines, AMD may be seeping into the water system and causing the issues at the prisons.

On another note, we project that the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station, owned by the Gilberton Power Company, has been dumping plant waste/coal ash into the Mill Creek and other tributaries of the Schuylkill County Municipal Authority, which runs directly into major SCMA Reservoirs (Shown Below).

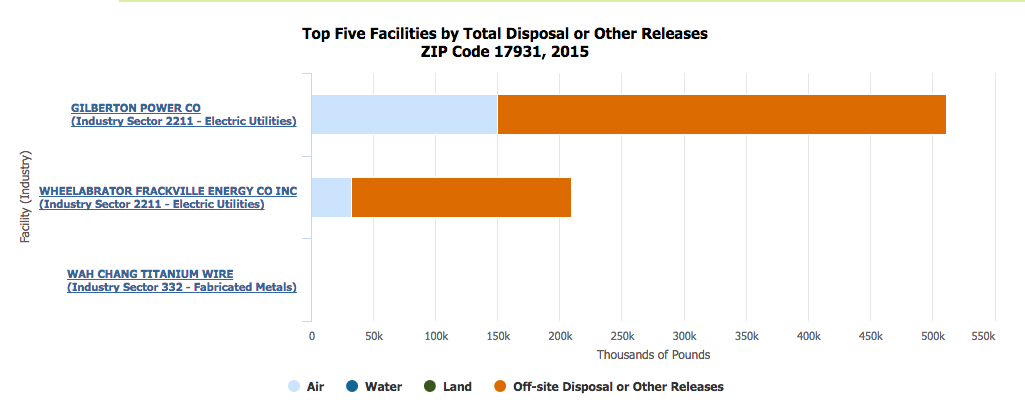

This anthracite culm burning plant, situated in between the prisons, generates approximately 590 million kilo-watt hours of energy per year by means of burning coal in a boiler to produce steam, which flows under pressure into a spinning turbine to generate electricity (See Visual 4). Since 2014, the power plant (with the purple pin) has had numerous violations (blue dots) of coal ash dumping since 2014 (See Visual 5). In addition, according to the EPA’s 2015 Toxic Release Inventory, the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station produces over 350 thousand pounds of waste that is disposed off site (shown below).

According to the Sierra Club and the EPA, 72% of all toxic water pollution comes from coal fired power plants dumping of heavy metals such as arsenic, selenium, boron, and mercury into waterways (Sierra Club, 2017). In addition, the majority of these power plants have no limit as to how much they can dump. To date, the majority of complaints about the plant have been air related in respect to asthma attacks; however, we argue that this persistent dumping of waste from the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station may be solely responsible, or in accordance with AMD, for the water contamination at the prisons.

Who is Acting to Combat the Issue?

Despite the severity of the issue, no single organization or individual has emerged as a leader in fighting for the rights of these prisoners. However, there have been several local organizations that have made efforts to raise awareness of the issue. Local prison advocates have held protests and petitions to raise awareness. One particular group that has been a key actor is, the “Friends and Family of Mumia Abu-Jamal” group. Mumia Abu-Jamal is an inmate at SCI Mahanoy serving a life sentence for the murder of a Philadelphia

police officer in 1981. As the first inmate to report the issue of contaminated water, the advocacy groups are utilizing him as the ‘face’ of the issue. By giving the injustice an actual face, organizations have turned this issue from one of inmate rights violations to one of a violation of human rights. Generally, the efforts made by all of the different groups have been pluralistic approaches such as protesting outside the institutions, coordinating public hearings regarding Mumia and water justice in prisons, and circulating online petitions demanding water testing at the facilities. While no deliberative acts have taken place, our contact, Joe Piette, claims that more academic and legal professionals have been asking how they could help the case. As such, as long as there is a mutual respect between both parties, deliberation tactics are the next step into seeing that inmates are treated as humans in regard to their water quality in prisons.

Who Should be Acting?

On the most local level, prison officials should be accommodating inmates, at least those infected with Hepatitis C, with bottled water. This was being done to accommodate all inmates; however, the cost soon became to much to bear for the prisons. If anything is to be done to put an end to this injustice, the EPA or the Pennsylvania Dept. of Environmental Protection need to take priority, accurately test the waters, and see to it that whatever is causing the contamination is fixed at the source as to avoid another happening in the future. However, despite notification from local advocacy groups, both have failed to properly intervene. Ultimately, on a more macro scale, if we are to resolve the issue of unclean drinking water in prisons, we need to stop polluting water in the first place. The Stream Protection Rule was once a piece of legislation that restricted coal companies from dumping mining waste into streams and waterways. This rule, although not always enforced with the best poli cing, was drawn up significantly restrict coal companies from destroying the ecosystem. According to Vox, the final rule of the legislation was passed in December 2016 and included both that “a company that wants to open a surface or underground mine needs to avoid causing damage to the “hydrologic balance” of waterways outside of its permit area and companies and regulators have to do a baseline assessment of what nearby ecosystems look like before any new mining begins. They then have to monitor affected streams during mining, and the company has to develop a plan for restoring damaged waterways to something close to their natural state after mining is done” (Plumer, 2017). While the bill showed promise, unfortunately, the Trump administration recently repealed the Stream Protection Rule to ease pressure on an already declining coal business and to avoid a possible domestic job loss from the increased costs companies would incur. As such, companies will now exploit the cheaper option of dumping and polluting our waterways, rather than utilizing pollution control.

cing, was drawn up significantly restrict coal companies from destroying the ecosystem. According to Vox, the final rule of the legislation was passed in December 2016 and included both that “a company that wants to open a surface or underground mine needs to avoid causing damage to the “hydrologic balance” of waterways outside of its permit area and companies and regulators have to do a baseline assessment of what nearby ecosystems look like before any new mining begins. They then have to monitor affected streams during mining, and the company has to develop a plan for restoring damaged waterways to something close to their natural state after mining is done” (Plumer, 2017). While the bill showed promise, unfortunately, the Trump administration recently repealed the Stream Protection Rule to ease pressure on an already declining coal business and to avoid a possible domestic job loss from the increased costs companies would incur. As such, companies will now exploit the cheaper option of dumping and polluting our waterways, rather than utilizing pollution control.

Historical Precedent

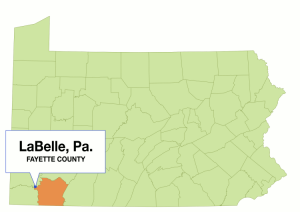

A strikingly similar injustice occurred in 2014 in La Belle, Pennsylvania. La Belle is located in Fayette County, near Pittsburgh. State Correctional Facility Fayette shared land with the Matt Canestrale Contracting Company – a business with a coal-refuse site, coal-ash dump and two coal-slurry ponds that served a nearby mine. Despite complaints from La Belle residents regarding the drift of coal ash around their homes, the prison was still constructed in 2003 on the land. By 2005, the prison was approximately 300 inmates over capacity with a population that was over fifty percent African American. In 2010, Eric Garland, one of the guards at the prison, contacted the Center for Coalfield Justice, an organization that “fights for coalfield communities through advocacy, education, and organizing”, after he himself was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism (Rakia, 2015). The CCJ forwarded the complaint to the Abolitionist Law Center, public-interest law firm that focuses on cases involving human rights abuses in prisons. The ALC conducted inmate interviews and found a striking amount of skin disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, thyroid issues, and even tumors. Not surprisingly, the exposure to coal ash, which contains toxins such as lead, mercury, and chromium, is usually associated cancer, lung disease, respiratory problems, and a variety of other potential issues.

A strikingly similar injustice occurred in 2014 in La Belle, Pennsylvania. La Belle is located in Fayette County, near Pittsburgh. State Correctional Facility Fayette shared land with the Matt Canestrale Contracting Company – a business with a coal-refuse site, coal-ash dump and two coal-slurry ponds that served a nearby mine. Despite complaints from La Belle residents regarding the drift of coal ash around their homes, the prison was still constructed in 2003 on the land. By 2005, the prison was approximately 300 inmates over capacity with a population that was over fifty percent African American. In 2010, Eric Garland, one of the guards at the prison, contacted the Center for Coalfield Justice, an organization that “fights for coalfield communities through advocacy, education, and organizing”, after he himself was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism (Rakia, 2015). The CCJ forwarded the complaint to the Abolitionist Law Center, public-interest law firm that focuses on cases involving human rights abuses in prisons. The ALC conducted inmate interviews and found a striking amount of skin disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, thyroid issues, and even tumors. Not surprisingly, the exposure to coal ash, which contains toxins such as lead, mercury, and chromium, is usually associated cancer, lung disease, respiratory problems, and a variety of other potential issues.

Coupled with their investigation, the ALC found that the infirmaries at the prisons often neglected or doubted the inmates’ complaints regarding the impacts of coal ash exposure. In spite of a follow up investigation by the Department of Corrections that reported that the water was safe to drink, environmentalists believed that the DOC was skewing their tests  and measurements (Sounds like Flint, MI). In reality, the DEP reported that the Tri-County Joint Municipal Water Authority had been exceeding the accepted safe level of trihalomethanes, a carcinogenic by-product of water disinfectant from chlorine, in the water. Although the community had been notified via quarterly notices about these high levels of trihalmethanes, the water company had failed to send notice to the inmates at Fayette. In 2014, the DEP renewed Matt Canestrale Contracting Company’s permit to continue dumping and despite the persistent minor lawsuits that the company receives, headway has been lost on the case.

and measurements (Sounds like Flint, MI). In reality, the DEP reported that the Tri-County Joint Municipal Water Authority had been exceeding the accepted safe level of trihalomethanes, a carcinogenic by-product of water disinfectant from chlorine, in the water. Although the community had been notified via quarterly notices about these high levels of trihalmethanes, the water company had failed to send notice to the inmates at Fayette. In 2014, the DEP renewed Matt Canestrale Contracting Company’s permit to continue dumping and despite the persistent minor lawsuits that the company receives, headway has been lost on the case.