Interview with Joe Piette

Matt: What is your background in regard to addressing this injustice we are seeing in State Correctional Institutions Frackville and Mahanoy?

Joe: Well I worked for the U.S. Postal Service for many years as a mail carrier, and when I retired about ten years ago, I joined the International Action Center in Philadelphia [According to their website, the IAC is “committed to the building broad-based grassroots coalitions to oppose to U.S. wars abroad while fighting against racism and economic exploitation of workers here at home. With every mobilization or campaign, the IAC strives to draw from the leadership, connect the struggles, and bring together communities of color, women, lesbian, gay, bi and trans people, youth and students, immigrant and workers’ organizations in order build a progressive movement for social justice and change”]. So we get issues reported to us all the time regarding healthcare, the Trump Administration, wage inequality, etc. I first heard about the water at the prisons in 2015 when one prisoner, Mumia Abu-Jamal, reported the brown water and the lack of attention the inmates infected with Hepatitis C were getting. However, they were handing out bottled water at the time Mumia told us, so we didn’t report anything. When they stopped distributing bottled water to the inmates and the problem continued, we decided we needed to start reporting the issue to shed some light on what was happening over there. To date, we have organized a few protests outside the prisons, gathered some community advocates, and circulated a couple of petitions to get the prisons to test the waters.

Matt: Do you know why the officials suddenly stopped distributing bottled water to the inmates? Do the guards drink the tap water?

Joe: Well they were giving the inmates bottled water for about four months in 2015, but we project that it just got too expensive. The guards have bottled water in their dining rooms at all times, but the inmates are allotted about a gallon of the contaminated water each day. It’s funny because every prisoner we interview says that the correctional officers say they would never drink that water—but the guys behind the bars don’t have much say.

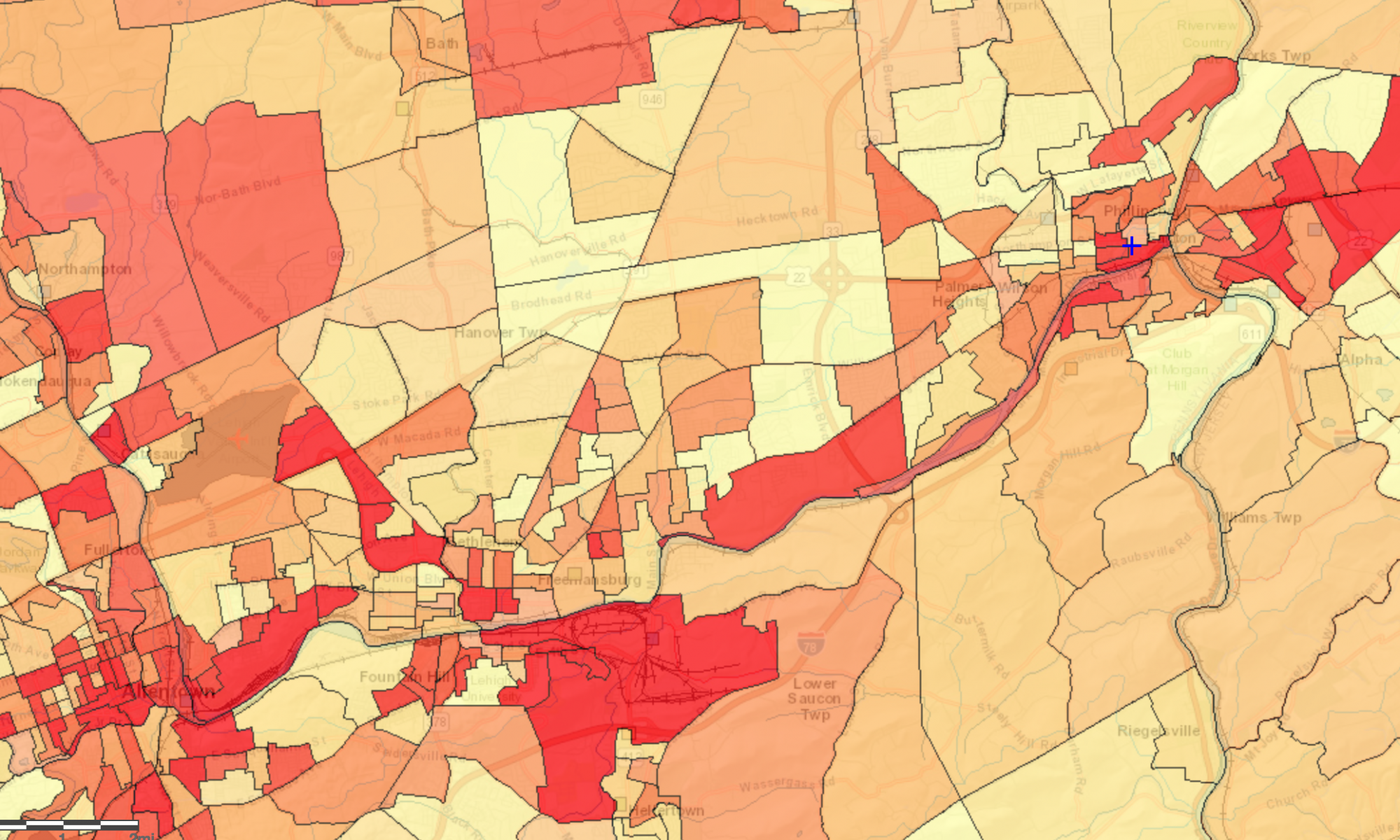

Matt: In our research we found that there were over 40 inactive anthracite coal mines that surround the areas of the prisons. On one hand, we project that acid mine drainage may be contributing to the water; however, there is also the problem of the John B. Rich Memorial Power Station dumping into Mill Creek. Has the IAC investigated the potential cause of the contaminated water?

Joe: I was unfamiliar with the inactive mines around the area, but that is something I will have to read up on. Currently, we are looking at the power plant as the main cause of the brown water because of the amount of coal they burn. They haven’t been very cooperative in our investigation. The town was actually going to build another coal plant next to SCI Mahanoy 10 years ago, but with the help of local advocacy groups and the signatures of over 500 inmates they actually got that permit denied. The water actually isn’t brown everyday—but rather might be slightly discolored and smelly on one day, foamy the next, then dark brown the following day. The inconsistency is why the cause is hard to pin down.

Matt: Have any organizations such as the Environmental Protection Agency, Pennsylvanian Department of Environmental Protection, or the Pennsylvanian Department of Corrections intervened by testing the waters?

Joe: We have contacted the EPA countless times and cannot even get a response. I don’t know if it is because we [IAC] aren’t a major business in the environmental industry or because it is an issue regarding inmates. The Department of Corrections only discussion of the institution at Frackville has been the potential closing of the prison because of PA inmate populations declining. However, they decided to keep it over to spare something like 400 jobs in the county. It’s not like it hasn’t been in conversation at federal levels, they just aren’t talking about the right things. In my opinion, I would have preferred if they closed it.

Matt: Do you fear that the issue has developed too much regarding the freedom for Mumia, as opposed to the idea of justice for all inmates in regard to the water contamination?

Joe: I do. The issues aren’t separate, but they are not entirely the same. Some people who protest for Mumia don’t even know about the water crisis in the prison he’s in—they just believe he’s innocent. At the same time, I don’t think we would be where we are in the process of fighting this issue if we didn’t frame it around Mumia. He makes the problem about human rights, and I think people like that. When people protest, they learn about everything going on in Frackville, and it is just more cause for them to support the issue.

Matt: So what are the next steps you and others are taking to combat the issue?

Joe: Well we just got in touch with a few radio stations in major cities that are helping report on the water in Frackville. Ideally, we hope to get someone like NPR run a story so news gets around. Because the water quality is so inconsistent day-to-day, we asked many of the prisoners to record which days are the worst. Last time I visited I collected a sample in the bathroom, but was told by a colleague that 48 hours was too long to test the water after its retrieved from the source. So when we know which days and times the water is at its worse, I plan on going in to grab a sample for testing. We still have to find a testing facility and are in contact with a couple colleges to possibly do so. Also, in a few weeks we are going to go around the community, ask people if they are using the Schuylkill County Municipal Authority, and see if they are experiencing similar water problems as the inmates. If we can make this a community issue, people will start to listen, and actions will be taken to address it.