Hello Farmers!

August has rolled in and we at the farm are seeing the benefits of all the work we put into our land, enjoying our pickings and looking forward to all the great autumn harvests we know we’ll have this year. Those harvests will be going to the dining hall, to the veggie van, and we will be selling at market on campus again when classes start.

Through all my work with LaFarm, interacting with the Veggies in the Community and other farms, and all my other Lafayette work that has brought me in contact with the Easton Farmers Market, Buy Fresh Buy Local, the Easton Hunger Coalition and others, I have always been most astounded by how much food and agriculture can so easily create a sense of community. Wherever I meet farm workers, farmers, gardeners, food distributors, cooks, or anyone else whose life revolves around food, whether it is at market, them visiting LaFarm, me visiting another farm, at a kitchen or anywhere else, there is always conversation to be had, information to be exchanged, goals to accomplish, and a friendly feeling of being in this life together with a shared purpose. That is one of the main advantages of centering one’s life around such a quintessential part of the human experience, the sense of community we all share.

Being in this community has brought me to look back at all the work we’ve done on the farm and take even more pride in what we’ve produced. So I took the time to bring together many of the pictures I’ve taken (and a few that I’ve been in) during this work:

- Zucchini Transplanting in mid July

- LaFarmers Miranda Wilcha and Peter Todaro look over the completed Zucchini bed

- Peter walking to the morning harvest while the Reiters work their community plot

- A desperately needed weeding in the cabbages

- Early morning potato harvest by Miranda as well as Leslie Tintle and VIC worker Rachel Young

- Peter manually watering newly planted Brussells Sprouts

- The LaFarm crew gathers to pull the last of the garlic

- Leslie, Miranda and me hauling the garlic harvest out of the field

- Miranda and Farm Manager Sarah Edmonds sitting under our hung-to-cure garlic

- The whole LaFarm crew taking a well deserved lunch break. From left to right it’s Sarah, Leslie, Alexa Gatti, Rachel, and Fletcher Horowitz.

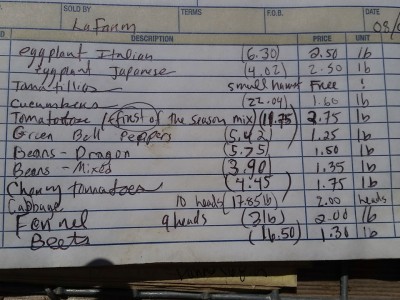

What we all can accomplish together is amazing. look at this harvest from just one day this summer:

- Garlic, laid out to cure

- Stacked heads of Savoy cabbage

- The first real beet harvest of the year

- A fine assortment of several different varieties of cucumber

- Beautiful fennel, ready for delivery

- Our invoice to BAMCO, listing everything we harvested this day.

From the ground work we have laid this summer, we expect harvests like this once or twice a week for the next few months, albeit with the exact types of vegetables changing a good deal over that time. Out of the rather small chunk of land we have, I definitely find this impressive, and I know that despite our struggles this is all possible because of the many, many hours of hard work that all of the people working or even just helping out once at our modest farm. So many thanks to Peter, Leslie, Miranda, Alexa, Rachel, Haley, Brandon, and all the volunteers and visitors we’ve had this summer, and of course a special thanks to Sarah, without whom none of this would happen, and Profs Lawrence, Cohen, Germanoski, Brandes, and all the others who help make the farm a part of Lafayette! I look forward to another great year as I enter my last Fall semester at Lafayette in this community of food workers.

Joe Ingrao, Summer 2015 EXCEL Scholar