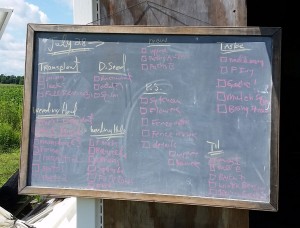

Here at LaFarm, we figured a good way to get closer to our land was to give our fields and plots their own names, rather than the traditional 1 2 3, or A B C. And not just any names were good enough for our fields, no we decided to make our whole farm a history lesson. Each field we have is named after a famous agriculturalist. We even chose a lot of the names for our specific fields because those fields connected to the legacies of the people they were named for. And then we also decided to name our shed Eliot Coleman and our Gazebo Jethro Tull to boot!

Eventually I’ll be going into some more detail about who each of these people are, but here’s a quick rundown of the important names we have at the farm.

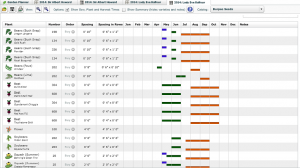

Sir Albert Howard

Many see Sir Albert Howard as the father of organic agriculture. Starting his work in England in the early 1900s, he was one of the first people to begin studying the effect of new agricultural chemicals on the health of the soil-and the nutrition of our food. Any familiar with Rodale over in Emmaus should know that it was information released by Howard that first shocked Jerome Irving back in the day to start all of his projects.

Lady Eve Balfour

If Sir Albert Howard was the father of the organic movement, Lady Eve Balfour was certainly the mother and, just like most mothers, ended up doing a lot more important things than Sir Albert in this humble farmer’s opinion. Howard started things off by studying them first, but Balfour started the Soil Association in England and really got the gears turning on an international alternative agriculture movement.

Masanobu Fukuoka

Because farming, and alternative farming, isn’t just a history of white people in the western hemisphere realizing that chemical agriculture isn’t sustainable, I made sure to bring up Masanobu Fukuoka (the original Japanese name order would actually make it Fukuoka Masanobu but he’s always referred to in the westernized order so that’s how it is here,) who pioneered what he calls “do-nothing” farming, which is a Japanese parallel to permaculture that uses no tilling, no chemicals, and not even pre-prepared compost. Doing this in Japan starting in the 40s and well into the 70s and 80s, Fukuoka was able to actual have yields that rivaled those of even the most chemically intensive farms in Japan. Also make sure to check out my small review of Fukuoka’s The One Straw Revolution on LaFarm’s Bookshelf.

Since he was very much about doing the least work for the most gain, we gave his name to our field of perennials.

Rudolf Steiner

Among this man’s many, many hobbies, he found the time to develop the idea of biodynamics a more extreme level of organic agriculture which has been both praised as amazing foresight and laughed at by others as complete insanity. The only people I know who’ve actually tried it all stand by the methods though. Just because hanging a deer bladder from a tree hasn’t been endorsed by modern agribusiness doesn’t mean it doesn’t keep pests away, and just because cow skulls aren’t in everybody’s compost doesn’t mean they don’t help aerate the soil.

We have a small field that does very, very well which we named after Steiner, because that’s kind of how biodynamics have been working.

Gary Paul Nabhan

First person on this list who’s actually still living, GPN is an amazing farmer out in the desert who emphasizes social connections and slow money for farmers in their communities. He came to speak here at Lafayette last year about the Monarch Butterfly Crisis, and found the time to make it out to look at our two humble acres. Since he’s so well known for keeping high organic matter in his soil (Seven Percent! Seven Percent! That’s astounding!!) we gave his name to a field that we’ve kept well maintained with cover crop and has more organic matter than most of our others.

Ruth Stout

Gardening in a similar tradition to Fukuoka, Ruth Stout was a proponent of “no-work gardening.” She was very actively part of the gardening scene for much of her long, 96 year life, and gets major respect from us for starting the roots of much of no-till farming in America in response to not wishing to be reliant on men to do the plowing before she could plant, or waste her own time doing what wasn’t necessary in the end.

Will Allen

The founder and leader of Growing Power, an urban agriculture group dedicated to helping feed Chicagoans with sustainably produced food, Will Allen is an important name in the local sustainable food discourse for all his great work. He focuses on equity (being a black man in an inner city, it is understandably a very salient issue for him and Growing Power), solving one problem at a time and not letting discouragement stop you, wisdom I think we could all follow. We named the closest plot to our entrance after this former professional basketball player, to remind ourselves that what we’re trying to do starts at the grassroots level, just like Allen did.

Joel Salatin

An expert in animal husbandry without using unsustainable practices, and well known among LaFarmers as the author of Everything I want to do is Illegal, Joel Salatin is a great farmer who is quick to point out the problems of big farming and the unnecessary obstacles facing local farmers.

Sandor Katz

Perhaps most well known for his ideas about wild fermentation, Sandor Katz is an openly gay culinary author who is well respected for his skill and innovation, and gains major props for being one of the Radical Faeries trying to shake up the establishment.

Wendell Berry

Although his Agrarian Populism is problematic in many respects (see the book Agrarian Dreams on our bookshelf for details on what I mean by that), we had to give a spot to the famous poet-farmer Wendell Berry. He’s been a voice for the alternative agriculture movement since the 1960s and 70s when he challenged USDA secretary Earl Butz in his support of big, chemical agriculture.

Karen Washington

If Will Allen is the face of urban farming in Chicago, this amazing woman is the face of urban farming in New York. She studied at the Center for Agroecology at the University of California Santa Cruz and took her skills back to the Bronx. She helped urban gardening in New York greatly with her aptly named Garden of Happiness.