Smartly produced and attractive paperback and hard-cover copies available at: https://www.camphorpress.com/books/kondo-the-barbarian/

Or download a free .pdf version from my Research Gate site: link

Book Review in Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History by John Kanbayashi:

https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/946978/pdf

Book Review in Taipei Times by James Robert Baron: https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2024/01/18/2003812257

New Books in Japanese Studies Podcast, Hosted by Ran Zwigenberg: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/paul-d-barclay-kondo-the-barbarian-a/id1534347682?i=1000642468113

University of Minnesota Book Club Discussion with Hiromi Mizuno: https://mediaspace.umn.edu/media/t/1_ki7ci6qm

Jonathan Clements Blogpost Review: https://schoolgirlmilkycrisis.com/2023/06/04/tales-of-the-ticktock-man/

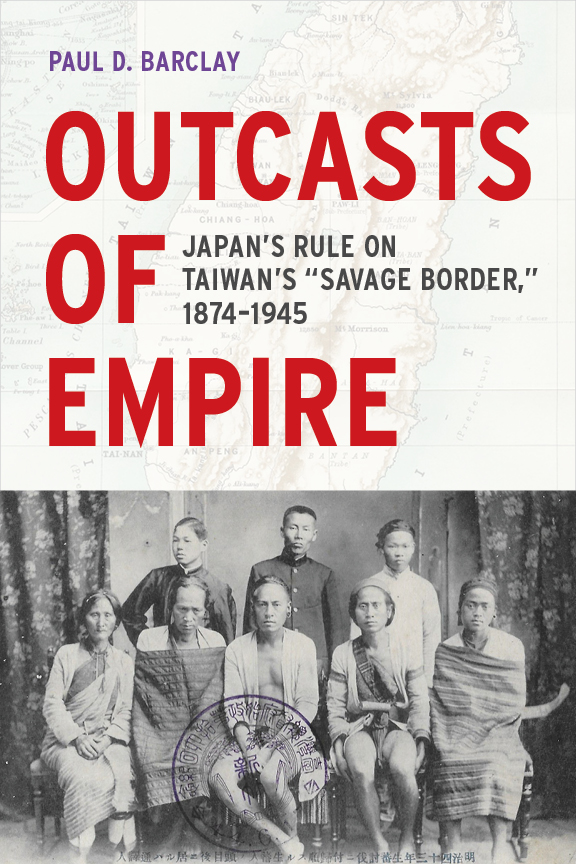

DESCRIPTION

Kondo the Barbarian is a gripping and revealing account of the colonial Japanese era in Taiwan, focusing on the Musha Rebellion and its brutal suppression by the Japanese military. The book presents the translated account of Kondō Katsusaburō, a Japanese adventurer who married into an indigenous Taiwanese family. Kondō’s journals offer an intimate and personal perspective on the events, though they can also be unreliable and prone to sensationalism.

To help readers navigate Kondō’s account, Barclay has provided a deeply-researched introduction, extensive notes, and context essential to understanding what really happened during the Musha Rebellion. The book sheds light on the cultural clashes and sporadic violence that characterized Taiwan during this period. Through the writing of Kondō, interpreted and contextualized by Barclay, readers gain insight into the complexities of colonialism, imperialism, and indigenous resistance.

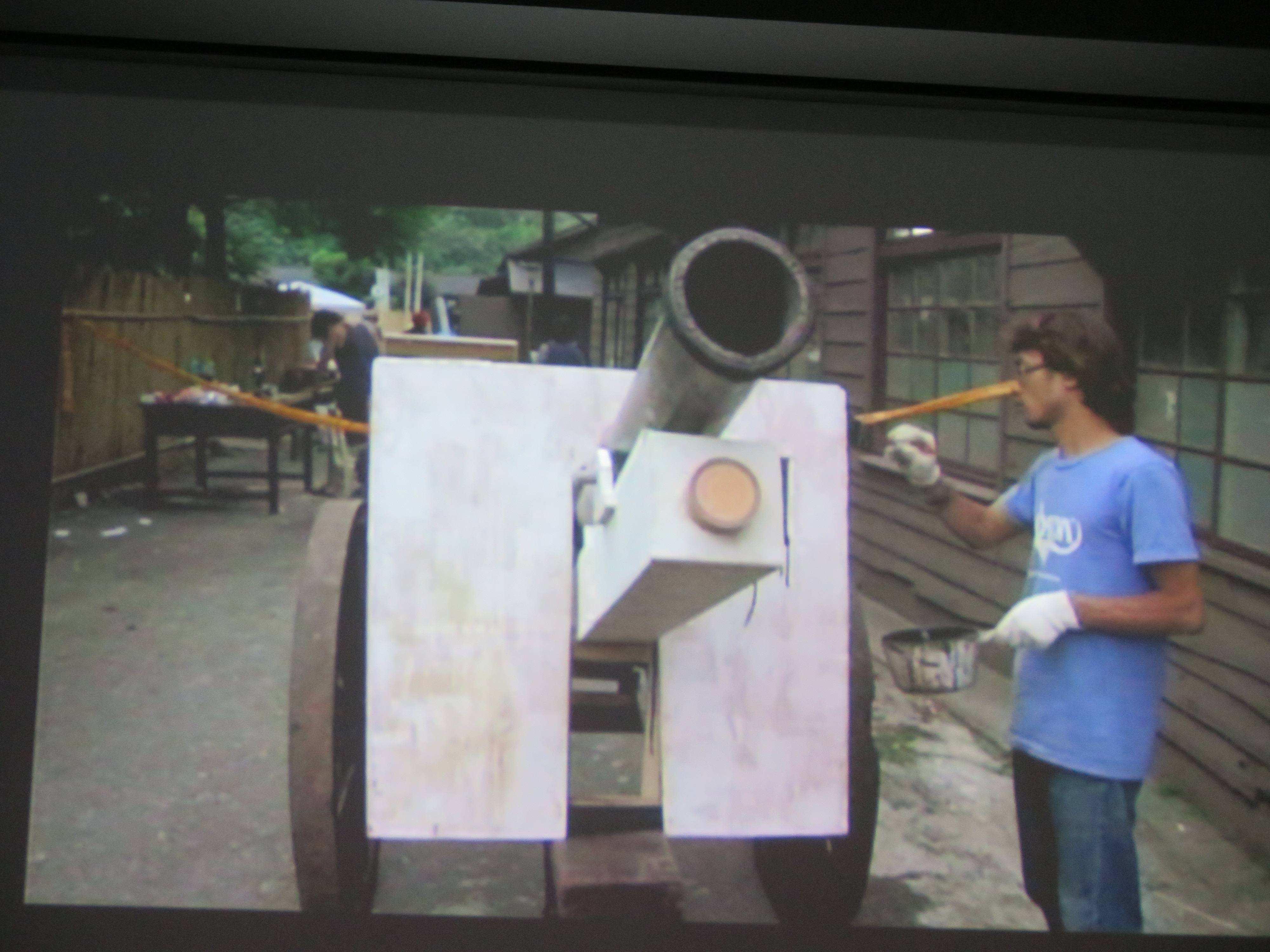

The Musha Rebellion was a pivotal moment in the relationship between the indigenous people and the Japanese colonial government. In 1930, after years of oppression, the Seediq people of central Taiwan, led by Mona Rudao, attacked a gathering of Japanese people at a local school, slaughtering over one hundred men, women, and children. The Japanese military responded with overwhelming force, employing tactics including poison gas, artillery, and aerial bombardment to quell the rebellion.

Barclay’s book offers a fresh and engaging perspective on a tragic chapter in Taiwan’s past, and the notes and context provided help readers understand the complexities of the events. The book is an important addition to the growing body of literature on Taiwan’s history, and it underscores the power of personal narratives to illuminate broader historical themes. Kondo the Barbarian is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of Taiwan, the contradictions of colonialism, and the challenges of interpreting personal accounts of historical events.

PRAISE

“Part fact, part fiction, an engrossing account of colonial benevolence and violence. Lucid, learned, and superbly translated, Kondo the Barbarian is an indispensable source for those interested in Taiwan’s colonial history, Japanese settlers’ writing and events leading up to the infamous 1930 Musha Uprising.”

—Leo T.S. Ching, author of Becoming Japanese: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation

“A fascinating account by a figure who lived a unique colonialist-adventurer life. Barclay’s expert introduction and notes demonstrate a first-rate historian’s skill to verify and contextualize Kondo’s account.”

—Sayaka Chatani, author of Nation-Empire: Ideology and Rural Youth Mobilization in Japan and Its Colonies

“This should become an essential source for understanding one of the most important acts of resistance to Japan’s rule of Taiwan and the complex relationships between Japanese colonizers and indigenous Taiwanese.”

—Evan Dawley, author of Becoming Taiwanese: Ethnogenesis in a Colonial City, 1880s-1950s

“Barclay not only gives us a masterful translation of Japanese colonialist Kondō Katsusaburō’s memoir but puts it into rich historical context. This book is an invaluable resource for understanding the ground-level dynamics of Japanese colonialism in Taiwan.”

—Seiji Shirane, author of Imperial Gateway: Colonial Taiwan and Japan’s Expansion in South China and Southeast Asia, 1895-1945

“Barclay’s beautiful translation brings Kondō the ‘Barbarian,’ a Japanese who lived with Indigenous Peoples in colonial Taiwan, back to life. Engaging, lucid, and illuminating. Highly recommended.”

—Hiromi Mizuno, author of Science for the Empire: Scientific Nationalism in Modern Japan

“Kondo the Barbarian ‘de-anonymizes’ the Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan, who are here individuals with names, life trajectories, and their own voices, in the process forcing the reader to reconsider the nature of colonial rule in Taiwan.”

—Nadine Willems, author of Ishikawa Sanshirō’s Geographical Imagination: Transnational Anarchism and the Reconfiguration of Everyday Life in Early Twentieth-Century Japan

“Barclay’s masterful research offers the reader critical context to understanding Kondo’s life and perspective, as well as the implications of Japanese colonial rule and the Musha Uprising for Taiwan’s history.”

—James Lin, Assistant Professor of International Studies at the University of Washington

“With the infamous 1930 Musha uprising as the historical underpinning of the book, Barclay introduces us to this world partly through the eyes of a Japanese adventurer – Kondō “the Barbarian” Katsusaburō – all the while never losing sight of the delicate interplay and agency of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples. A story that resonates beyond time and place.”

—Kirsten Ziomek, author of Lost Histories: Recovering the Lives of Japan’s Colonial Peoples

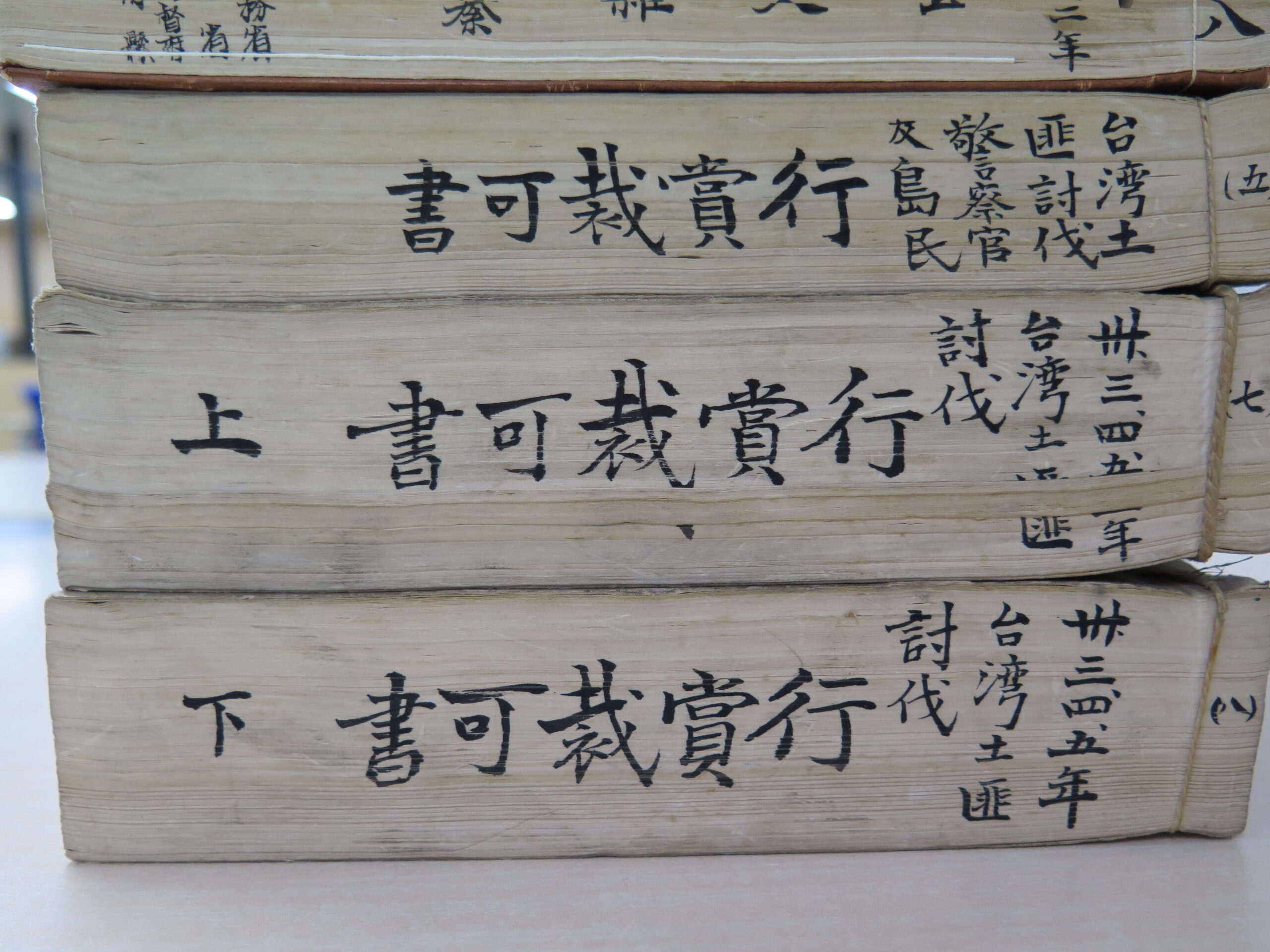

I was interested in battlefield honors for Japanese soldiers, and other forms of compensation, which are documented in a large collection of manuscript records in this repository.

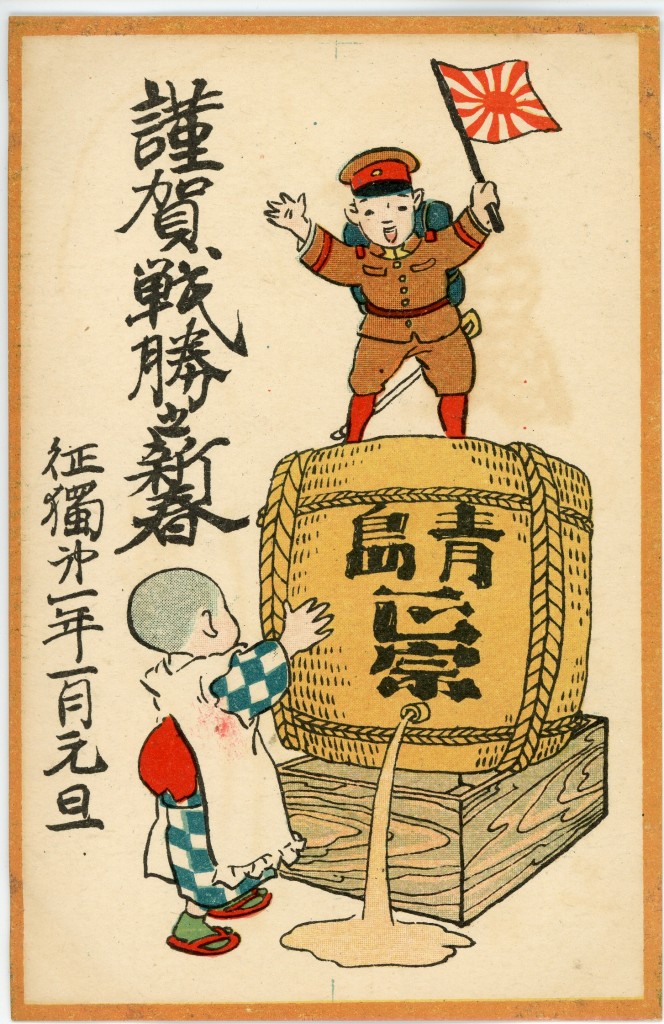

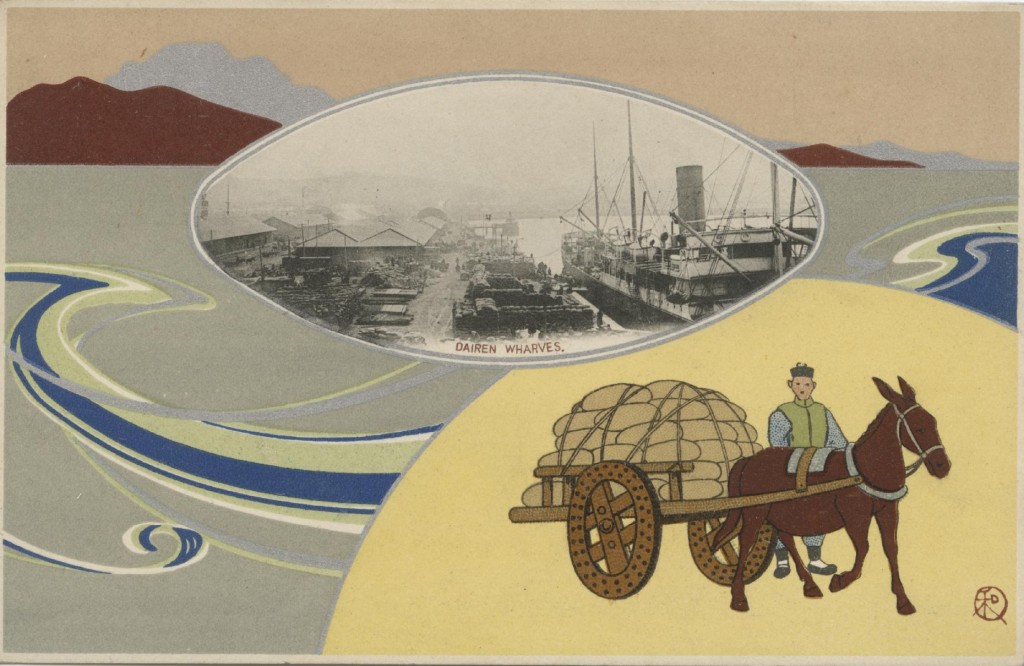

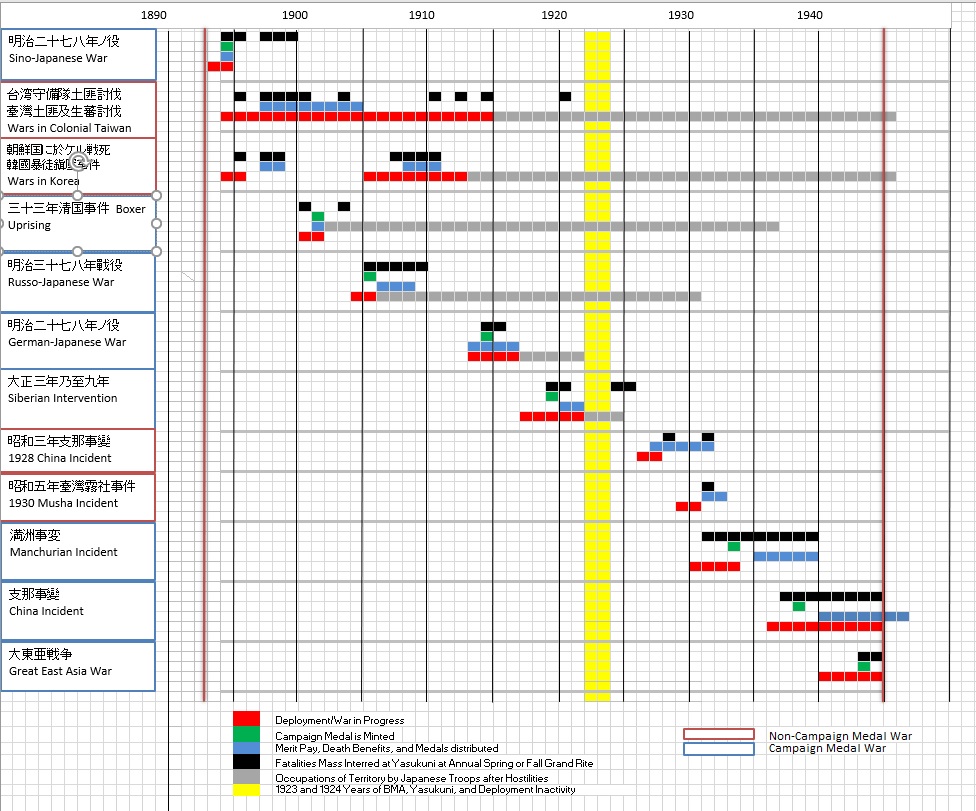

I was interested in battlefield honors for Japanese soldiers, and other forms of compensation, which are documented in a large collection of manuscript records in this repository. Based on the documents and catalogs, I made a chart to think about the temporal experience of “wartime” for families, soldiers, and sailors directly connected to military funerals, awards disbursement, and after-war occupations of foreign lands. This resulting chart suggests a nation at war from 1895 through 1945.

Based on the documents and catalogs, I made a chart to think about the temporal experience of “wartime” for families, soldiers, and sailors directly connected to military funerals, awards disbursement, and after-war occupations of foreign lands. This resulting chart suggests a nation at war from 1895 through 1945.

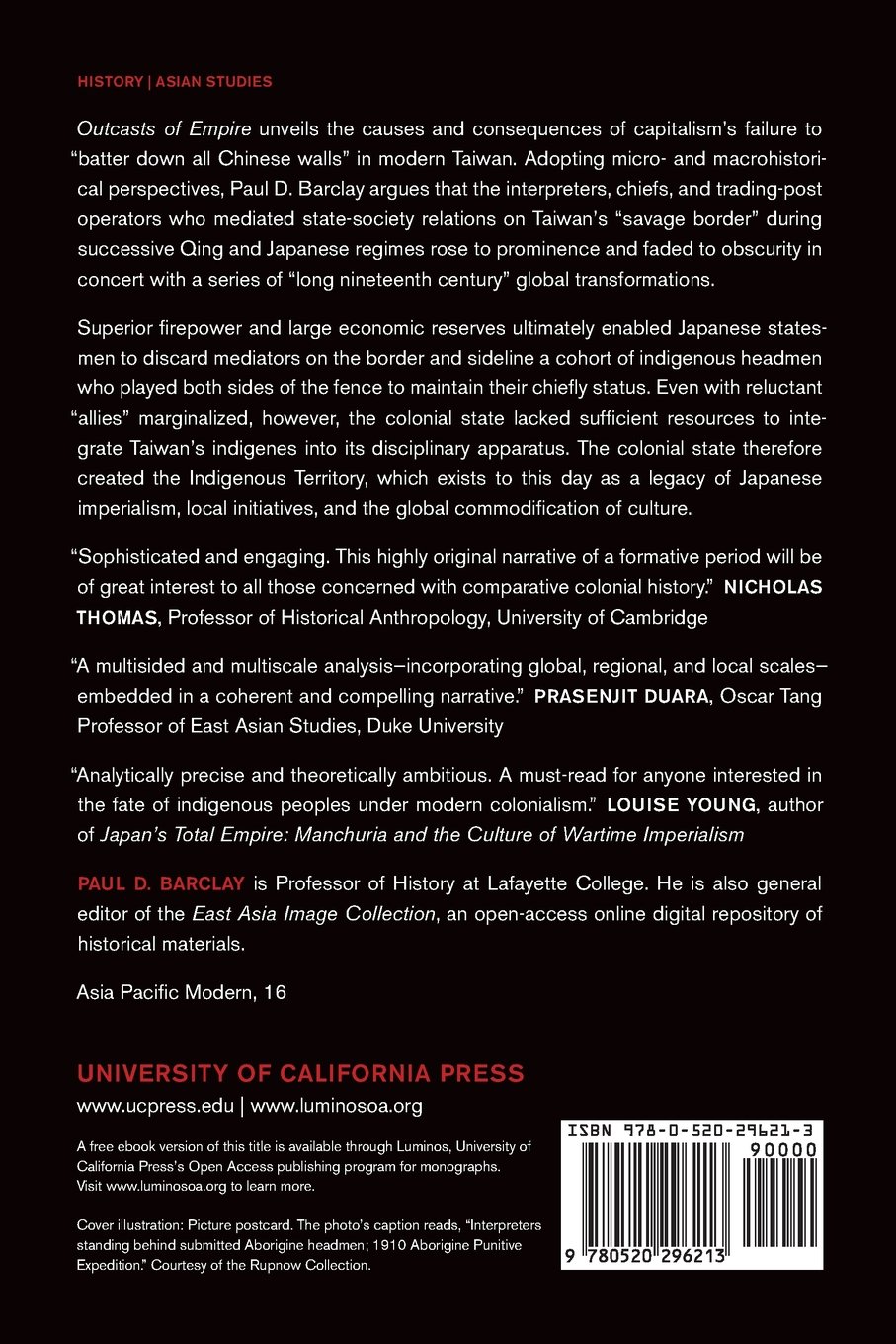

Front row: Kieu-fen Chiu, Darryl Sterk, Paul Barclay, Bob Tierney, Dakis Pawan, Wan Jen, Leo Ching. Middle Row: Jiajun Liang, Toulouse-Antonin Roy. Back Row: Michael Berry, Bakan Pawan, Deng Shian-yang, Wu Chien-heng, Ping-hui Liao

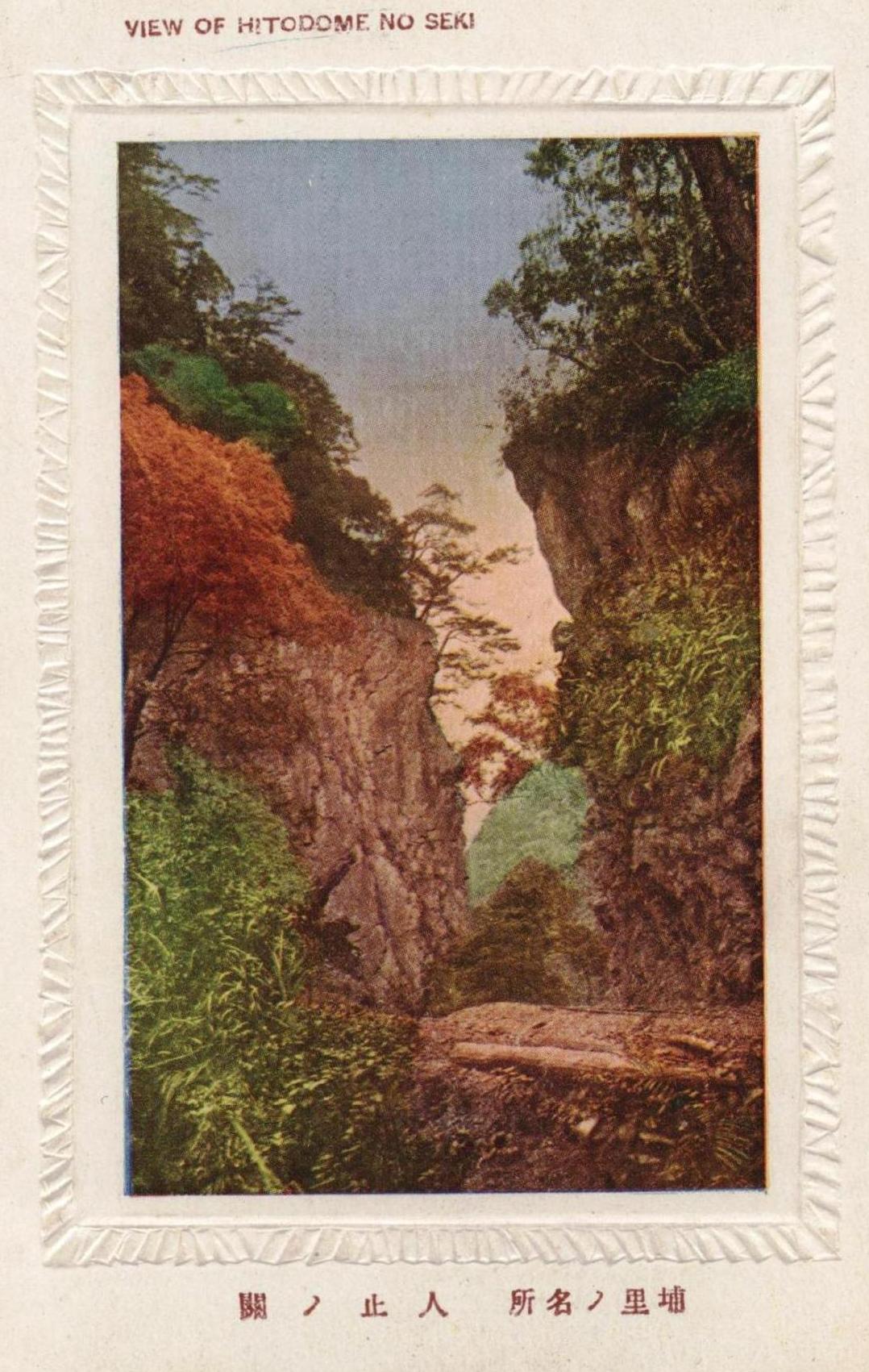

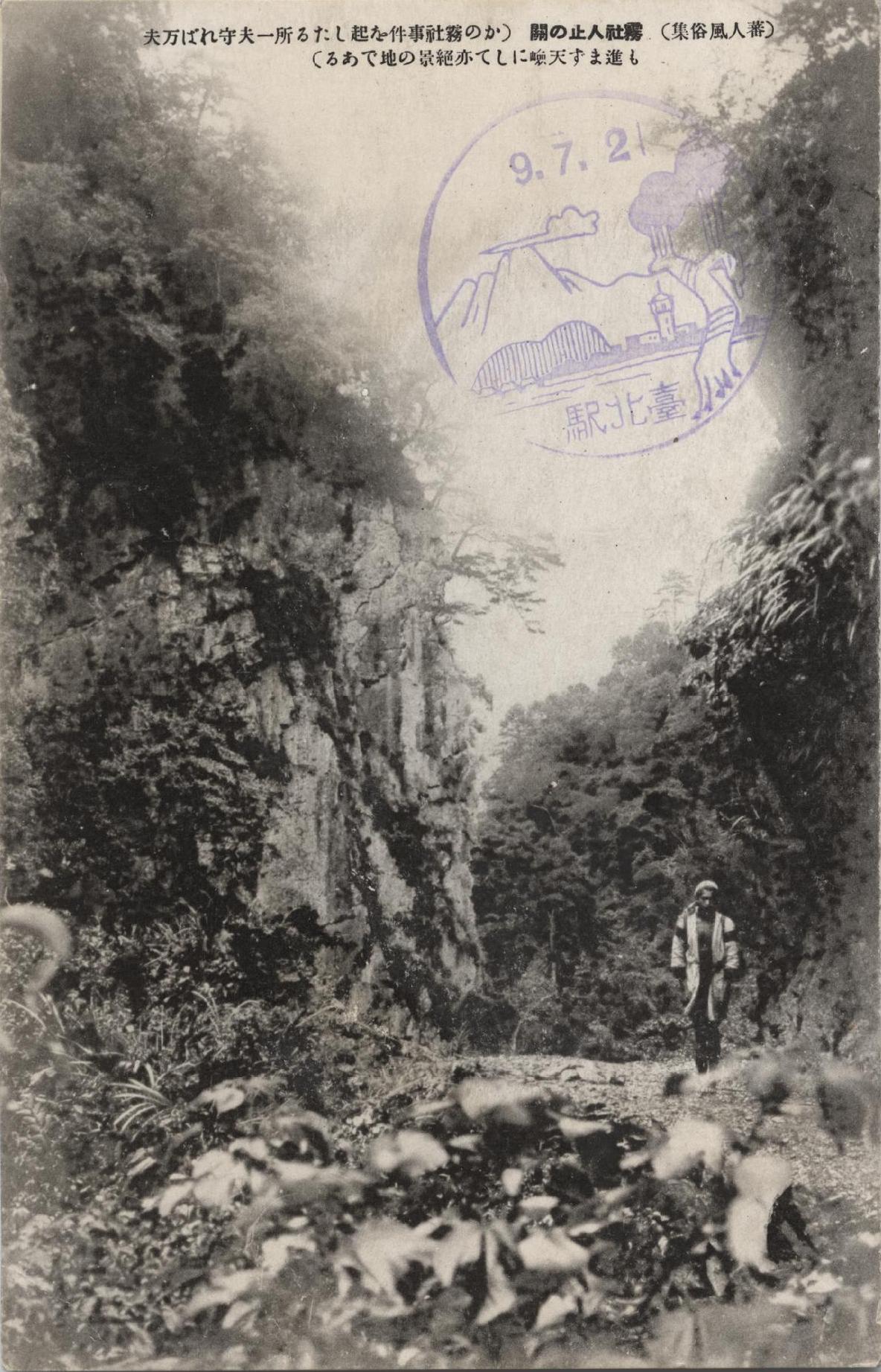

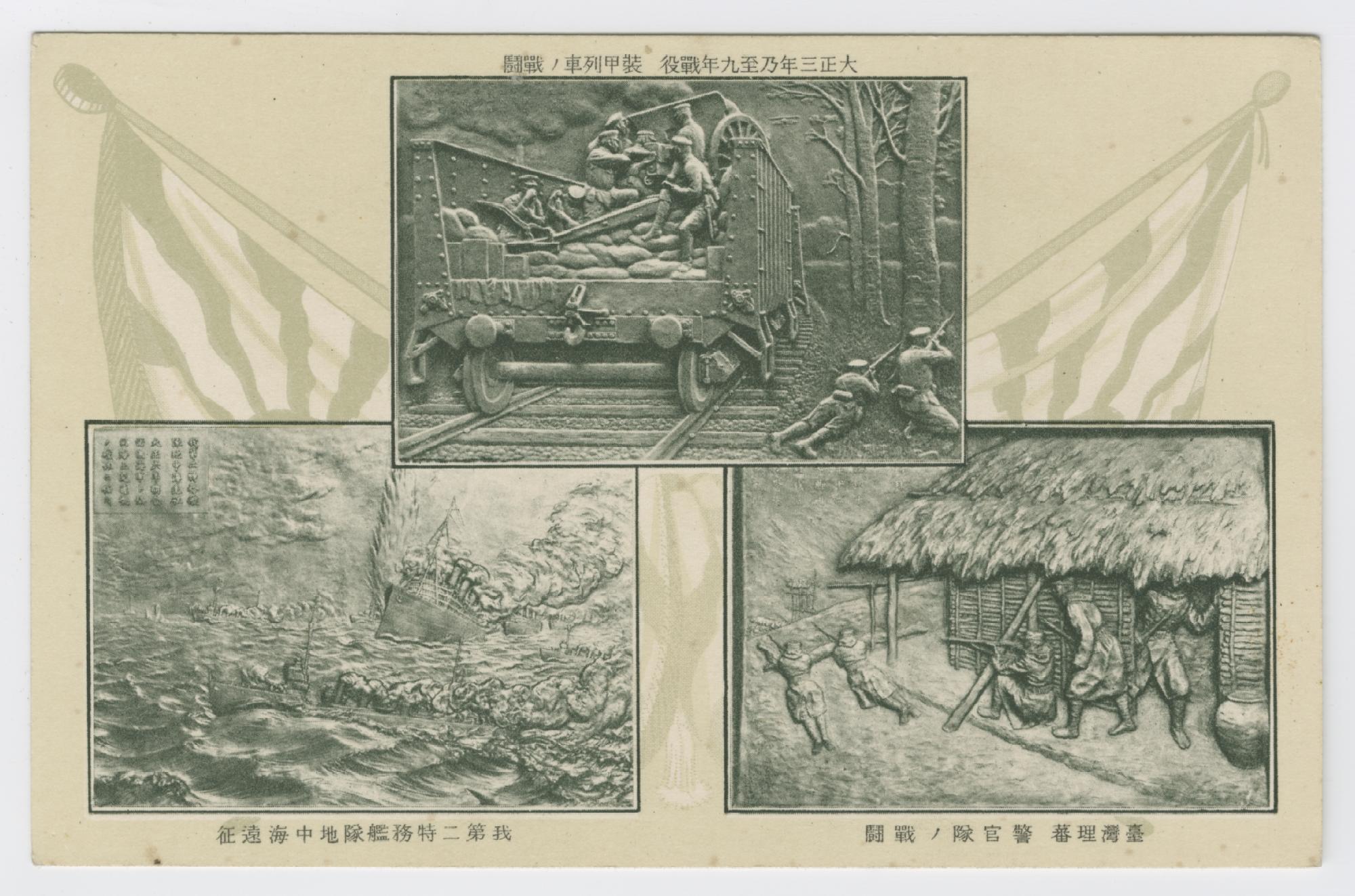

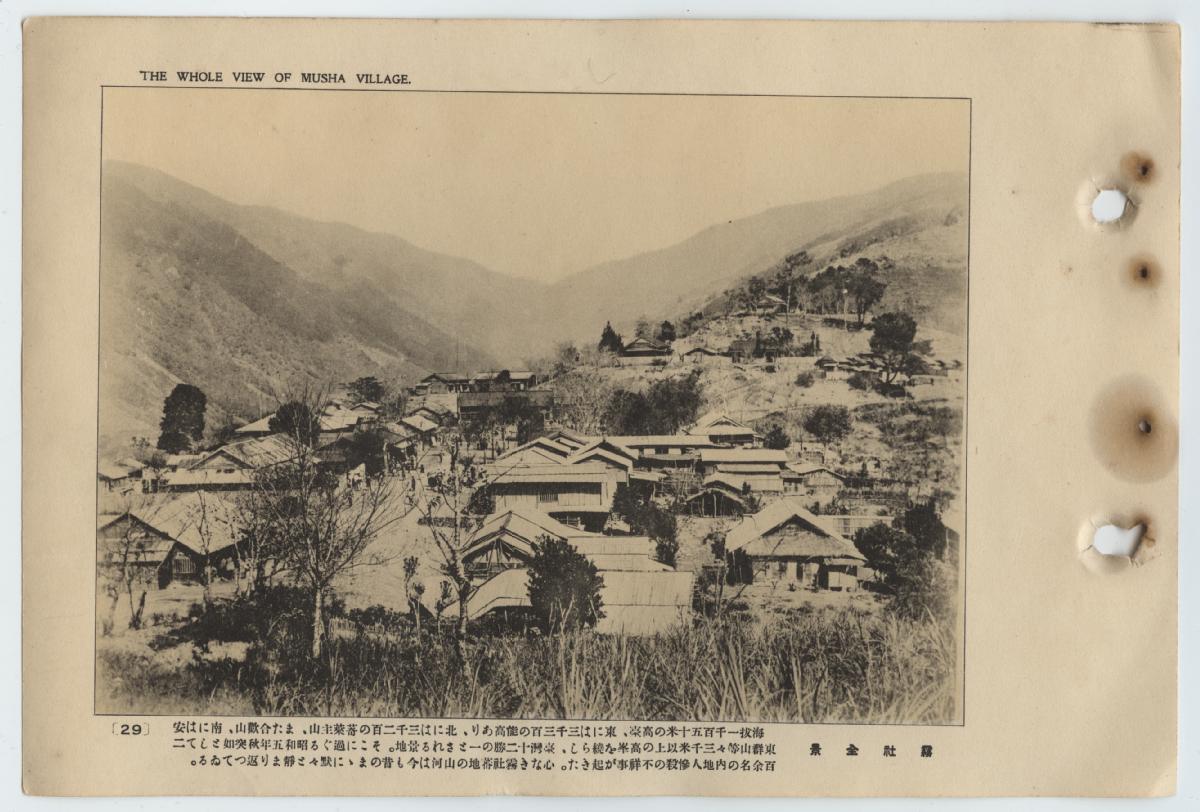

Front row: Kieu-fen Chiu, Darryl Sterk, Paul Barclay, Bob Tierney, Dakis Pawan, Wan Jen, Leo Ching. Middle Row: Jiajun Liang, Toulouse-Antonin Roy. Back Row: Michael Berry, Bakan Pawan, Deng Shian-yang, Wu Chien-heng, Ping-hui Liao 1930s postcard of the Japanese memorial to the fallen from the Musha Incident.

1930s postcard of the Japanese memorial to the fallen from the Musha Incident. Ren’ai Township, 2010, possible site of the former Japanese monument.

Ren’ai Township, 2010, possible site of the former Japanese monument.

Ren’ai town in 2010 (formerly Wushe).

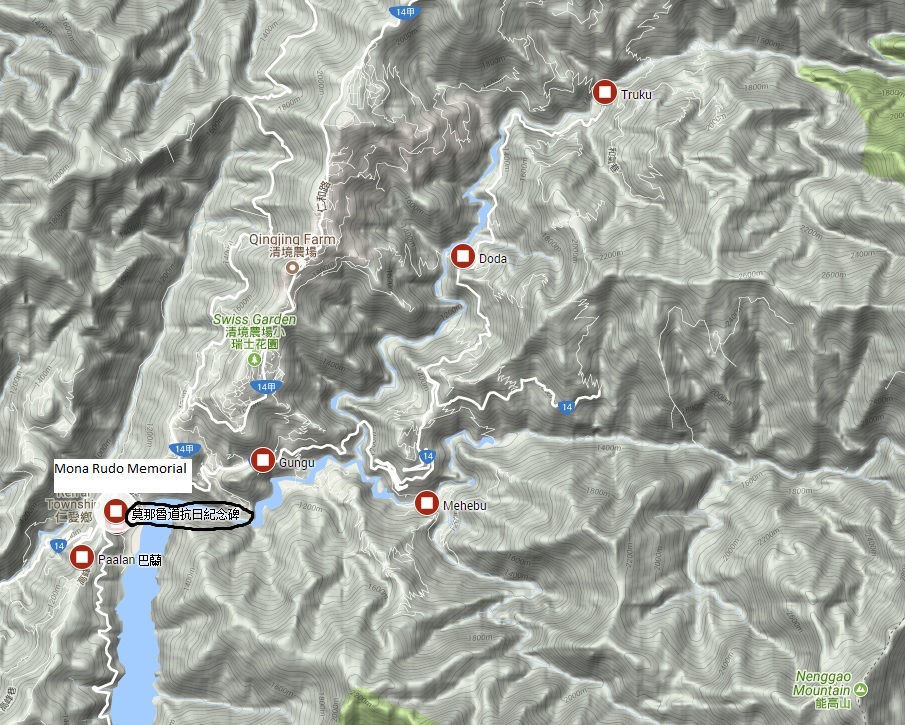

Ren’ai town in 2010 (formerly Wushe). Site of the Mona Rudo Anti-Japanese Commemoration Monuments (above on google maps; the next five images are from this site)

Site of the Mona Rudo Anti-Japanese Commemoration Monuments (above on google maps; the next five images are from this site)

Statue of Mona Rudo, 2010, near Ren’ai township, Nantou Province

Statue of Mona Rudo, 2010, near Ren’ai township, Nantou Province The grave of Mona Rudo, 2010

The grave of Mona Rudo, 2010

Derryl Sterk, Dakis Pawan and Bakan Pawan make plenary remarks

Derryl Sterk, Dakis Pawan and Bakan Pawan make plenary remarks (Above) Workshop organizer, film and literature scholar Michael Berry, filmmaker Wan Jen and historian Deng Shian-yang discuss Wan Jen’s 20-hour TV series Dana Sakura, based on story by Deng Shian-yang (next two photos)

(Above) Workshop organizer, film and literature scholar Michael Berry, filmmaker Wan Jen and historian Deng Shian-yang discuss Wan Jen’s 20-hour TV series Dana Sakura, based on story by Deng Shian-yang (next two photos)

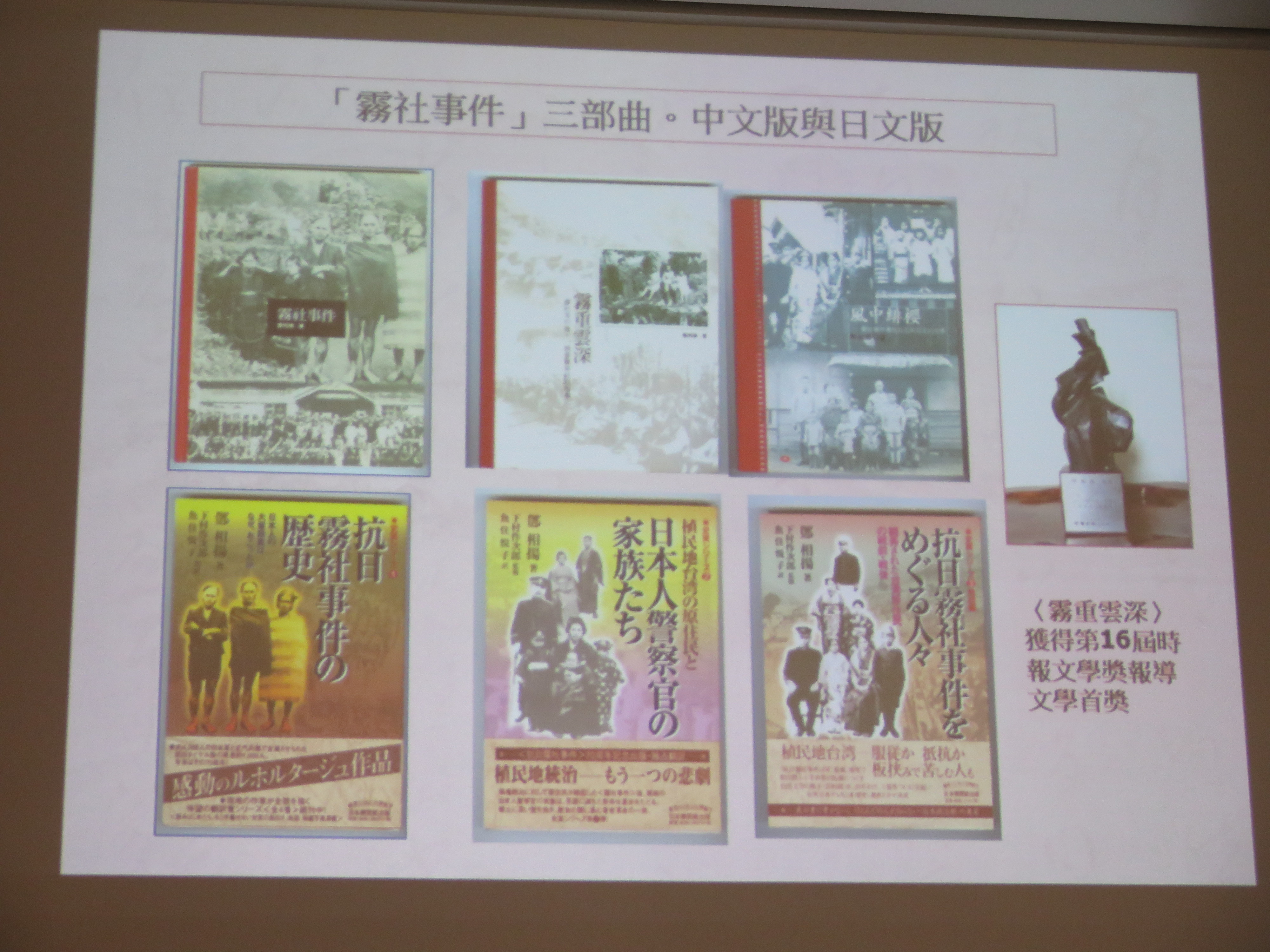

Deng Shian-yang’s pioneering books about the Musha Incident

Deng Shian-yang’s pioneering books about the Musha Incident Leo Ching, author of the first English-language scholarly treatments of the Musha Incident and the famous book Becoming Japanese.

Leo Ching, author of the first English-language scholarly treatments of the Musha Incident and the famous book Becoming Japanese.  The lodging for the workshop attendees, right on campus.

The lodging for the workshop attendees, right on campus.