March 31-April 3, 2011, Honolulu Hawai’i (Hawai’i Convention Center)

March 31-April 3, 2011, Honolulu Hawai’i (Hawai’i Convention Center)

Statue in front of the Convention Center

This was a great conference not only for the weather and beautiful surroundings, but also for the experience of participating on a panel with so many learned scholars, who are also wonderful colleagues. Here’s our panel:

Session 300: Behind and Beyond the Lens: Photography in Imperial Japan, 1896-1945

Organizer: Paul D. Barclay, Lafayette College, USA

Chair: Laura Hein, Northwestern University, USA

Discussant: Laura Hein, Northwestern University, USA

This panel examines photography in its multiple roles as instrument, beneficiary, and victim of empire. Specifically, the papers consider conquest photography in Taiwan (1890s), commercial photography in Korea (1910s-1930s), a newsreel photographer in China and Taiwan (1930s), and art photography during the Fifteen Year War (1930s and 1940s). As these case studies demonstrate, photography surely aestheticized violence, obfuscated power relations, and pandered to voyeurism to make empire emotionally plausible, even attractive. At the same time, we argue that the relationship between the gun and the camera in imperial Japan could be quite oblique, if not troubled. By considering imperial photography as a dynamic enterprise, engaged in by amateurs, professionals, and artists under varied technological and political constraints, we draw attention to discontinuities and dead ends. Though camp followers in 1890s Taiwan were urged to push the medium’s limits as an instrument of mobilization, for example, the state thwarted photographic engagement with war in the 1940s. Moreover, we argue that specific material forms were suited to different kinds of ideological work. While photographs of carnage in Nanjing and Wuhan filled commemorative albums, postcards and glossy brochures retailed images of exotic and contented fellow Asians. For all of its diversity, however, Japanese imperial photography produced a singular cumulative effect. Decades of variation upon a limited number of themes, the incessant reproduction of a pool of stock images, and the wavering support of an overweening state overdetermined imperial Japanese photography’s exhaustion as a vital force by the end of its 50-year career.

Colonial Itineraries: Japanese “Conquest Photography” in Taiwan, 1896-1899

Joseph R. Allen, University of Minnesota, USA

My paper explores early photographic production by the Japanese colonists in Taiwan as manifested in two halftone printed albums (shashinchō), dating from 1896 and 1899. I argue that the first of these albums, that documenting the military campaign to conquer the island in 1895, established a general structural and thematic shape for later albums, including for the travel guide seen in the second album. In part, this was in the photographic trope of “encampment.” Not only did this early “conquest narrative” inform later albums, it also offered a general heuristic model by which the island came to be known to both the colonizing power and the colonized subject. The island was construed as an entity to be known as an itinerary, not as a residence. Those early models continued to inform photographic constructions of Taiwan throughout the colonial and even into the postcolonial period, contributing to the island’s ongoing state of conditionality—that is, its social reality always being construed as dependent on another cultural agent.

Romancing the “Conquered Other” in the Korean Peninsula: Travel Myths, Images, and the Imperial Tourist Gaze

Hyung I Pai, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

Visages of dancing courtesans and white-robed peasants framed by decaying ruins of pagodas, temples, and palaces are the most recognized tourist images representing the time-less beauty of Korea’s cultural landscape. This study traces the colonial origins of travel photography, postcards, and guidebooks mass produced by Imperial Japan’s travel industry when they expanded into the newly acquired colonies in Korea and Manchuria in the early twentieth century. Following decisive military victories in the Sino-Japanese (1895) and Russo-Japanese War ( 1905), both public and private, large and small operators from international steamship liners, Japan Tourist Bureau (JTB), the Korea Branch of the Japan Imperial Government Railways Co., South Manchuria Railways Co. and local Japanese settlers’ owned businesses (trams, taxi cos. station hotels, hot springs inns, photographic studios, newspapers, department stores, geisha houses) in colonized cities and towns worked together to lure the growing numbers of colonialists, leisure tourists, students, soldiers, and businessmen to purchase round-trip packaged tours via Japan, Korea and Manchuria (Naichi). This paper analyzes how geo-political factors, aesthetic preferences as well as commercial agendas have determined the selections process of a handful of highly romanticized and exoticized ‘stock images’ representing ‘Koreana’ targeting a world audience for more than century.

When a Thousand Words aren’t Worth a Single Picture: Harrison Forman, The China War and Propaganda by Misdirection

Paul D. Barclay, Lafayette College, USA

This paper analyzes the uniquely detailed documentation left behind by newsreel photographer Harrison Forman regarding conditions for photographers in 1938 Taiwan. It attempts to explain how an otherwise enterprising investigative reporter became an unwitting mouthpiece for Japanese imperialists. For despite the damning observations recorded in his diary, Forman published a sympathetic account of the Government General’s work in Taiwan. Photography as a medium, I argue, tipped the balance. At the height of the second Sino-Japanese War, police restrictions on the movement of photographers operated in tandem with profligate image distribution. By shunting foreigners off to model villages in the interior and providing lavish hospitality in resorts, as well as numerous photo-opportunities, ever-present police minders helped recast Japanese colonial rule as a civilizing mission vis-à-vis Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples. Forman returned to America in possession of an ostensibly eye-witness photographic record of Indigenous Taiwanese customs and manners, buttressed by officially distributed photographs of Japan’s struggles to stamp out headhunting in the recent past. This thematically consistent visual record simply overpowered the doubt-ridden scribbles in Forman’s notebook. Not only was Taiwan’s role in the war on China thus obscured, but repressive policies in urban Taiwan were pushed to the background.

A War Without Pictures: Photography’s Curious Position in Wartime Japan

Julia Adeney Thomas, University of Notre Dame, USA

Between 1937 and 1945, Japan’s government and the military used almost every imaginable means to mobilize the nation behind the conquest of Asia. Technologically capable and aesthetically astute, Japanese photographers also sought to inspire public support for imperialism, and yet, as I will argue, photography never galvanized the nation. This paper raises two questions. First, why did photography not play a bigger role in the Japanese war effort, especially given the culture’s sophisticated understanding of the visual arts? In comparison with America and Europe, there are few canonical pictures of Japan’s struggle, sacrifice, victories and defeats during the years of fighting. The magazines produced for the domestic market were drab compared with the glossy, glorifying publications produced for the non-Japanese market. Aesthetic experimentation, rather than being harnessed to energize the war effort, was discouraged. In short, what does it tell us that Japan’s war was, in essence, a modern war where photography played a surprisingly limited role? My second question follows on from the first. Is photography the same the world over as many photography theorists insist? If photographs in wartime Japan played a different role than they did in other militarized nations, it shows, I argue, that this “universal technology” is far from universal. I will demonstrate how social and ideological conditions in Japan constructed a distinct place for the photographic image in the 1940s.

I also made my first visit to the Pearl Harbor historic sites run by the national park service. I visited the history museums attached to the USS Arizona memorial, also known as the “WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument.”

The historic sites include the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park, the Battleship Missouri Memorial, and the Pacific Aviation Museum. www.pearlharborhistoricsites.org

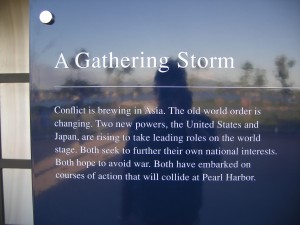

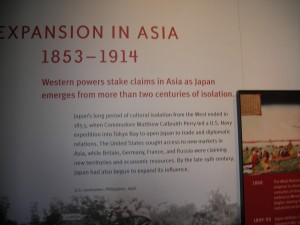

Of particular interest to me was the historical framing of the attack at the exhibit. The “sneak attack” idea has been considerably tempered by a much broader analysis of twentieth century history. In essence, as the gateway plaque below indicates, the attacks were prefaced by a century of Pacific expansion by the U.S. and Japan (1853-1941). This longer view is more consonant with that put forth by serious scholars of Japanese history, who try to understand how a more-or-less “normal” industrialized power (for the time) would embark on such a seemingly self-destructive course. Interestingly, I bumped into a historian on the shuttle boat to the memorial who had consulted for the museum as a Japanese expert. This historian suggested that the initial drafts of the textual component of the museum were in dire need of such expertise. On the whole, I think the park service did a creditable job on this museum.

“A Gathering Storm” is different than a “Day that will live in Infamy”

“A Gathering Storm” is different than a “Day that will live in Infamy”

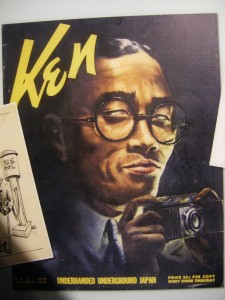

But the story of Yoshikawa Takeo, the spy who sent photographic information about Oahu (where Pearl Harbor is located) to Japan still gets pride of place.

But the story of Yoshikawa Takeo, the spy who sent photographic information about Oahu (where Pearl Harbor is located) to Japan still gets pride of place.

U.S. pop culture from the 1930s. Perhaps a “clever” people, Japanese were not considered by many to be capable of standing toe-to-toe with a the U.S. Navy in a real war. A classic case of misunderestimation.

On this poster, European activities in the Pacific are aggrandizing, while the American presence is characterized as a “search for markets.” And yet, a picture from the Philippines 1898, site of a bloodily aggressive U.S. territorial conquest, is affixed below the ambiguous captioning. Certainly an example of exhibit by committee. On the one hand, the United States is not the same kind of imperialist aggressor as the Europeans and Japanese, but at the same time, it is in global competition for resources, markets and territories. And so it goes.

what a nice information