Imperial China Graphic

I found an old tattered b/w diagram of “Status and Power” hierarchy in Imperial China in my teaching folders. This diagram was produced by G. William Skinner. It was brought to my attention by Edward L. Farmer, at the University of Minnesota. I scanned it and used my Adobe Illustrator to update it. I’ve not found a better shortcut to explaining, in a simple way, how misleading the tag “peasant” can be as a social category. If you like this image, let me know and I’ll send you a file.

INDS 140: A History of Japanese Culture and Government

January 7th: Hiroshima Peace Park, Museum and Related Sights. This is a picture of the “A-Bomb Dome,” or 原爆ドーム. The building was erected in 1914 as an industrial promotion hall. It was near the hypocenter of the August 6th, 1945 atomic-bomb attack.

The A-Bomb Dome has come to symbolize the destruction wrought by the weapon. It is being carefully preserved as a monument to the attack, and has been under consideration for World Heritage Site status:

The A-Bomb Dome has come to symbolize the destruction wrought by the weapon. It is being carefully preserved as a monument to the attack, and has been under consideration for World Heritage Site status:

Here is the approach to the Peace Memorial Museum, which includes the Memorial Cenotaph (designed by Kenzo Tange). The students spent a few hours in the museum and looking at the various monuments in the area, also known as the Peace Memorial Park.

The monuments, parks and museums contain the world “Peace” but the content of all of these sites are related to war, and to a specific war at that. Within a general message that the bomb is a scourge of humanity, and that nuclear weapons must be destroyed to make the earth safe, is a competing story about why the bomb happened to fall on Hiroshima of all places (and not, say, Sidney or Rome). Several plaques in the museum, and at least one memorial statue speak to the role of the Japanese military as an aggressor in China and Korea leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor:

While the first ten or so panels in the museum’s chronological exhibits highlight Hiroshima’s military function in the wars against China, this next plaque indicates how the focus remains upon Japan’s suffering. Even in a discussion of the horrible wars that cost China twenty- to thirty million lives, the effects of economic belt-tightening at home are emphasized. Yet this plaque at least acknowledged the place of China and Korea in the larger story:

While the first ten or so panels in the museum’s chronological exhibits highlight Hiroshima’s military function in the wars against China, this next plaque indicates how the focus remains upon Japan’s suffering. Even in a discussion of the horrible wars that cost China twenty- to thirty million lives, the effects of economic belt-tightening at home are emphasized. Yet this plaque at least acknowledged the place of China and Korea in the larger story:

Throughout our in-country class, we’ve noticed that most signs for tourists appear in Japanese, English, Korean and Chinese. And we’ve heard all of these languages spoken at various sights and sites. Regarding the atomic bomb, there is also a sub-plot in the museum about Korea’s victimization at the hands of Japan. There is also a special monument built to the Koreans who perished in the blast:

Throughout our in-country class, we’ve noticed that most signs for tourists appear in Japanese, English, Korean and Chinese. And we’ve heard all of these languages spoken at various sights and sites. Regarding the atomic bomb, there is also a sub-plot in the museum about Korea’s victimization at the hands of Japan. There is also a special monument built to the Koreans who perished in the blast:

First memorial service for the Koreans who suffered from the attack (1968):

First memorial service for the Koreans who suffered from the attack (1968):

The monument to the Koreans who died or survived, built by an association of Koreans who are resident in Japan:

The monument to the Koreans who died or survived, built by an association of Koreans who are resident in Japan:

Taken as a whole, it would seem that students, tourists, and visitors of any sort are left to sort out the meaning of the museum, the park, and the various monuments in Hiroshima for themselves. While the preponderance of images of suffering and destruction focus the local Japanese, there are hints, texts, and suggestions sprinkled throughout the complex that suggest a reality about A-Bombs that is more difficult than simply declaring “no more Hiroshimas” in annual proclamations. As a history teacher, I hope that Hiroshima’s monuments and placards will continue to evolve until a more regional perspective can be presented.

Interestingly, the Shukkei-en, a large Japanese garden that was built by the Asano clan of “Chushingura” fame, has preserved even more evidence of the complexity of A-Bomb memory politics. This monument, which is sustained by the prefecture, invokes a story-line that is recounted in John Hersey’s book Hiroshima. Namely, that Japanese military and police authorities were quite slow to react to the bombing and help victims. Here is a sign at the “Shukkei-en,” presumably the “Asano Park” mentioned in Hersey’s book:

In addition to the a-bomb related activities, we also visited the prefectural museum of modern art, ate Hiroshima-yaki (a seafood/noodle/pancake/pork dish) and rode the street cars around town.

In addition to the a-bomb related activities, we also visited the prefectural museum of modern art, ate Hiroshima-yaki (a seafood/noodle/pancake/pork dish) and rode the street cars around town.

January 6th: Osaka Castle and the 4th Army divisional headquarters. Both built in 1931 w/public subscription. Osaka castle was originally the stronghold of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who is considered by most to be the unifier of Japan (ca. 1590). He also launched invasions of Korea and NE China in the 1590s, as did the Japanese Army in 1931. So there are linkages between the old division headquarters and the castle, though they are not apparent in the signage.

4th Army division HQ (1931-1945)

4th Army division HQ (1931-1945)

Northeast Asia Interconnections

Northeast Asia Interconnections

First photo for trip:

Course Description:

Between 600 and 1868 AD, the literary, religious, architectural, artistic and culinary elements of Japanese civilization were created, refined, and re-invented in tandem with a number of reconfigurations of Japan’s political structure. Over the course of these twelve centuries, before Japan’s political and economic center shifted eastward to Tokyo, most major developments occurred in western Japan, and revolved around the imperial courts in and around Kyoto.

This interim course will immerse students in the aesthetic and political history of a nation which gave the world its first novel, Zen Buddhism, epic war poetry, samurai castles, sushi, and a number of internationally admired performance and artistic traditions. Within Japan’s sometimes elaborate, and sometimes austere cultural structures, distinct codes of conduct and governance also flourished, and have survived well beyond the passing of the old feudal orders. Through a combination of directed readings, language study, site visits to major monuments, participation in cultural demonstrations, and lecture/discussion classroom activities, students will gain a basic grounding in this most complex and storied history.

While we are in Western Japan, we will also take a day trip to Hiroshima to visit the Peace Park and the sites related to the atomic-bomb attack. Below is a memorial to Hiroshima’s past as a departure point for naval vessels en route to East Asia theaters of war.

Korea in the World: Linkages and Legacies

A Symposium at Lafayette College

November 11, 2011 (Friday) 1:00pm-4:30pm Wilson Room Pfenning Alumni Hall

Korea’s role in international affairs since World War II has been as profound as it is well known. But the impact of international affairs on the history of the peninsula, and on the lives of over seventy million Koreans, has received comparatively less attention in the American academy. The purpose of this symposium is to add balance and depth to our understanding of Korea’s role in international affairs by moving beyond the frame that considers Korea as the stage upon which other people’s history is acted out. In this context, “linkages and legacies” refers to this symposium’s goal of keeping a traditional focus upon Korea’s connections with regional and global structures and dynamics, while putting equal emphasis on the longer history of how entanglements with the international system have impacted Korean society since the 1870s. In short, “linkages and legacies” asks how the history of Korea’s role in international relations would look if equal weight were given to studying the impact of international relations on the history of Korea.

Program

1:00pm: Welcome, Introductory Remarks:

Angelika von Wahl, International Affairs Program, Lafayette College

Panel One: Linkages

1:15 pm:

Andrew Yeo, Catholic University, Department of Politics

“Anti-U.S. Base Movements and the Politics of Peace on the Korean Peninsula.”

1:45pm:

Il Hyun Cho, Cleveland State University, Department of Political Science

“Nuclear Proliferation and Regional Orders: The Multidimensional Challenge of North Korea and Iran.”

2:15 pm:

Comments by discussant and questions from the audience

Panel Two: Legacies

2:45pm:

Seo-Hyun Park, Lafayette College, Department of Government and Law

“Korea’s Search for Sovereignty in the Late 19th Century.”

3:15pm:

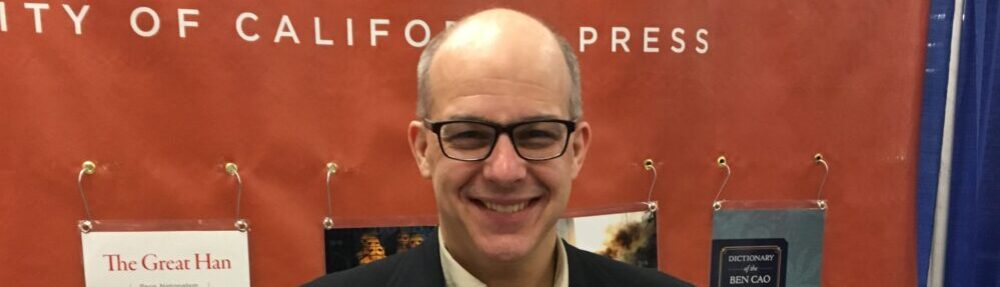

Paul Barclay, Lafayette College, History

“Korea in the Visual Economy of Japanese Empire: Comparisons with Colonial Taiwan, 1905-1945.”

3:45pm:

Comments by discussant and questions from the audience

Conclusions

4:15pm:

Robin Rinehart, Lafayette College, Chair of Asian Studies and Department of Religious Studies

Closing remarks and general discussion

This event sponsored by: Department of History, Department of Government and Law, Asian Studies Program, Skillman Library, Policy Studies Program, International Affairs Program and the Dean’s Office of Lafayette College.

a. Linkages

In 1945, with the defeat of Japan, Korea was divided at the 38th parallel by the United States and the Soviet Union. After disarming Japan, Washington and Moscow backed their respective “client states” in a three-year war (1950-1953) that left millions of Koreans dead while devastating the cities, farms and fields of the peninsula. Henceforth, the U.S. acted as guarantor of allied regimes in South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and South Vietnam. This global war against socialism, communism, and anti-imperialist nationalism put the United States and the Soviet Union on a permanent state of military preparedness known as the Cold War.

Today, the Cold War is becoming a memory in Europe and the United States, while Korea remains divided and finds itself at the epicenter of another dispute that involves both Koreans and outside powers. In 2011, the 38th parallel separates one of Asia’s most vibrant and wealthy capitalist democracies from the world’s most diplomatically isolated and impoverished socialist regime. No longer of value to its former communist patrons as a model for socialist development, North Korea (DPRK) has become reliant on the development of nuclear weapons as its only international bargaining chip. As one of the most infamous examples of a “rogue state,” North Korea has become a flashpoint for current international anti-nuclear proliferation disputes.

Whereas in the early 1950s Koreans played host to contending Chinese, Americans, and Russians whose major priorities were geo-strategic and only secondarily regarded the interests of Koreans, the Six Party talks of more recent vintage display a similar mixture of motives and agendas: some local, but most geo-strategic.

b. Legacies

While these two watersheds, the beginning and end of the Cold War, mark the most well known conjunctures of Korean history and international affairs, events on the Korean peninsula have portended epochal shifts in global balances of power and transformations of the international order for some 150 years. In the late nineteenth century, the United States, Japan, Russia, China, and England all targeted the so-called “Hermit Kingdom” for foreign investment, missionary activity, and diplomatic intrigue. In the face of foreign pressure, patriotic Koreans founded reform movements to secure popular sovereignty in the face of dynastic inertia and the imperialist threat. These movements sent Korean scholars, statesmen, and soldiers to East Asia, Europe, and North America in search of aid and solutions. Today, in the Republic of Korea, this late-nineteenth century burst of intellectual, political, and technological creativity is an important reference point for imagining a progressive, democratic Korean future that is not contingent upon externalities for its integrity and dynamism.

Before these efforts could bear fruit, however, Japanese, Chinese and Russian armies fought each other in Korea to deny the peninsula to rival states. As a result of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, Korea lost its sovereignty, though not its relevance. As a colony or protectorate of Japan from 1905 to 1945, Koreans launched a popular press, authored modern literary movements, started up industrial enterprises, and fought armed resistance against the colonizers, creating the nationalist, capitalist, and anti-colonial impetuses that defined post-liberation politics after the Japanese defeat.

c. Linkages and Legacies

Thus, we argue, the history of Korea before the Cold War must be understood before the dynamics of contemporary Korean interactions with the world can be comprehended. Therefore, we dedicate our first panel to detailed analysis of two aspects of this lesser known, pre-Cold War period of “Korea in the World.” These papers will focus on pre-1945 “legacies” that have continued to shape developments and consciousness on the peninsula well into the 21st century. The second panel, “Linkages,” will focus on the Korea’s place in the global security system. Both presenters in this second panel will add new perspectives as scholars well grounded in the languages and histories of Korea and East Asia.

Northeast Asia Interconnections

From July 30 to August 16 Lafayette Students visited various cities in China and Korea as part of an interim course to study political, cultural, migratory, and historical interconnections in Northeast Asia. Luckily, the teachers for the course allowed me to tag along.

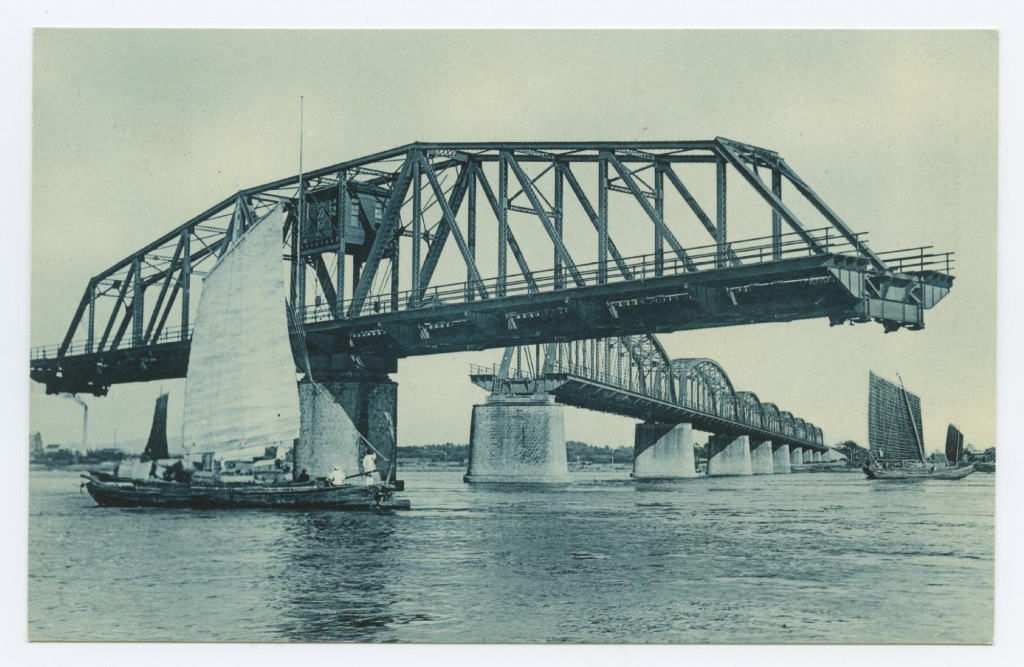

These photos are from the bridge that connects Dandong, China to Sinuiju, DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). One of the bridges carries freight and passengers between the two countries, and the other has been left damaged as a reminder of the American bombing campaigns of the war known as the “Korean War” (1950-53) in the United States.

The Ferris Wheel is on the DPRK side of the river

The Ferris Wheel is on the DPRK side of the river

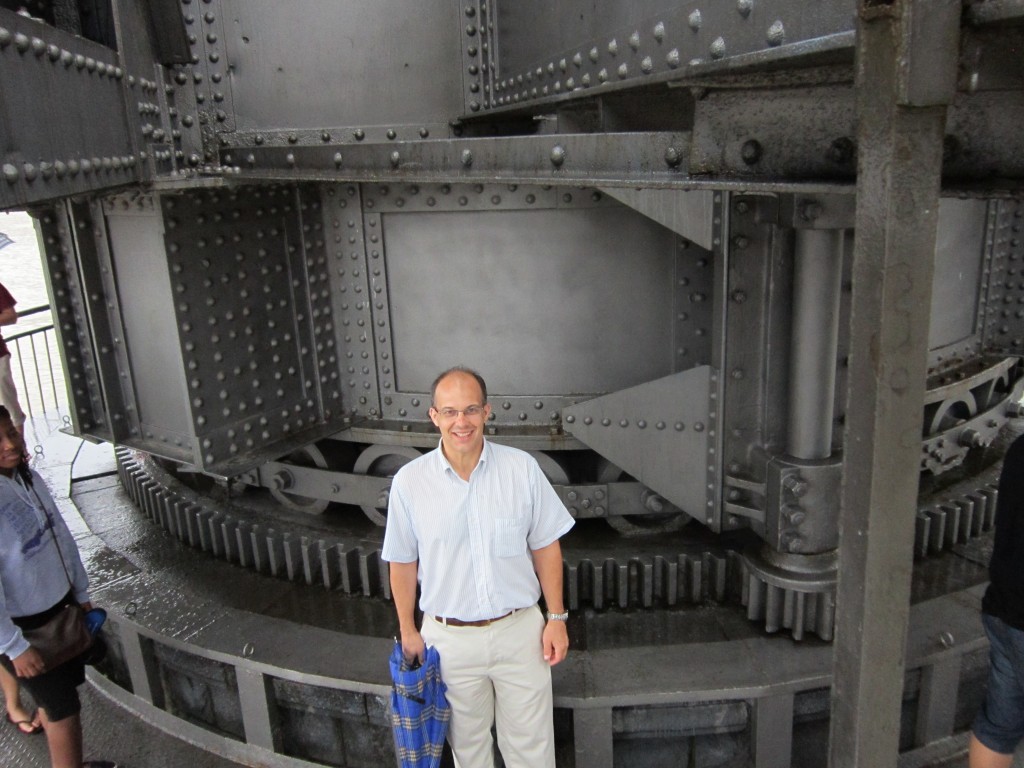

The un-reconstructed bridge was built by the Japanese after the “protectorate” was established in 1905. This bridge was the subject of many a Japanese publicity photo advertising the modernity of the colonial regime. This signboard explains this bridge as an “engineering marvel” because of the horizontal revolving beam that allowed a section of the bridge to become perpendicular to the rest of the bridge to allow the passage of tall ships. According to this sign, the bridge was built in 1908.

The un-reconstructed bridge was built by the Japanese after the “protectorate” was established in 1905. This bridge was the subject of many a Japanese publicity photo advertising the modernity of the colonial regime. This signboard explains this bridge as an “engineering marvel” because of the horizontal revolving beam that allowed a section of the bridge to become perpendicular to the rest of the bridge to allow the passage of tall ships. According to this sign, the bridge was built in 1908.

The gear works of the Dandong-Sinuiju Bridge have been turned into a mini-museum, which seems to be an unwitting tribute to Japanese colonial engineering

The gear works of the Dandong-Sinuiju Bridge have been turned into a mini-museum, which seems to be an unwitting tribute to Japanese colonial engineering

Japanese postcard of the Dandong-Sinuiju bridge ca. 1920

Japanese postcard of the Dandong-Sinuiju bridge ca. 1920

Another Japanese postcard of the “swing bridge” over the Yalu. ca. 1930

Another Japanese postcard of the “swing bridge” over the Yalu. ca. 1930

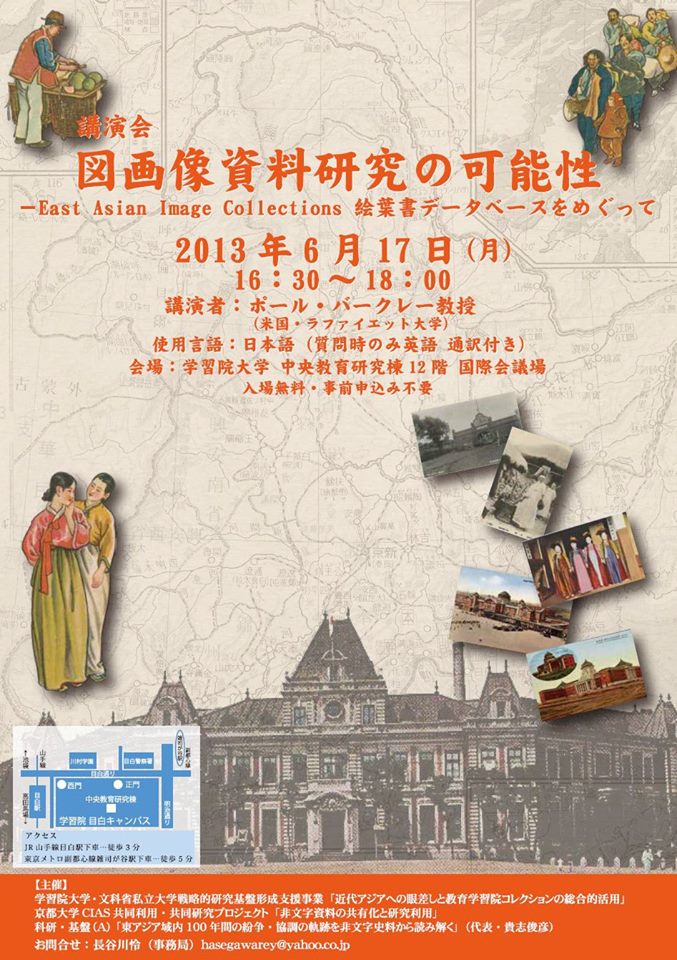

Asian Studies Japan Conference, Tokyo

Thanks to the organizers and my fellow panelists for an informative conference in Tokyo, and especially thanks to Yamamoto Masashi and Vicky Muehleisen for putting up with me for a whole week!

Thanks to the organizers and my fellow panelists for an informative conference in Tokyo, and especially thanks to Yamamoto Masashi and Vicky Muehleisen for putting up with me for a whole week!

Session 35: Room 316

The Exhibitionary Complex and the Police State: Imperial Pedagogy in Taiwan under

Japanese Rule

Organizer: Paul Barclay, Lafayette College

Chair: Robert Eskildsen, J.F. Oberlin University

This panel conceptualizes several examples of imperial pedagogy in colonial Taiwan as parts of an “exhibitionary complex.” Japanese visionaries, employing techniques explored in the papers, configured the peoples, places, and built environment of Taiwan as a series of exhibits to be viewed, categorized, and displayed for the purposes of statecraft, economic gain, and discipline. By shifting the focus of culture-studies inspired scholarship to individual “exhibitors,” and the agency of the “exhibited,” these papers also argue that colonial “exhibits” were constructed in a context of intra-governmental conflict and local constraints. Caroline Hui-yu’s paper shows how the 1925 Taipei Police Exhibition, ostensibly staged to instruct Taiwanese subjects in “everyday modernity,” could also serve as an arena of competition between recently arrived Japanese policemen and “Taiwan Hands” for influence in the colonial state. Sōyama Takeshi’s paper analyzes government-sponsored tourism as a mechanism for enforcing spatial boundaries between Japanese and Taiwanese in the realm of leisure, while tourism also sought to erase boundaries in the realm of political identity. During the post-1937 period, Taiwanese subverted this pedagogical enterprise by disguising trips to Chinese folk temples as visits to Shinto shrines. Paul Barclay’s paper argues that model villages in Taiwan’s “indigenous territories” failed as commercialized tourism “exhibits.” Nonetheless, they provided image-hungry foreigners with photo-ops that played upon shared Japanese and Western assumptions about the place of indigenes in the international order. These journalists portrayed Japan’s polices favorably abroad, thus vindicating a security apparatus often at odds with the tourism industry.

1) Hui-yu Caroline Ts’ai, Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

Everyday Coloniality, Social Networking, and Knowledge Production: The 1925 Taipei Police

Exhibition

The interwar years serve as an intriguing period for the analysis of “everyday coloniality.” Following current academic interest in questions of “vision,” this “new” turn of colonial studies tends to rest on a rich ground of “things visible” and “tangible.” The problem, however, is that history is more often than not being abridged or curtailed, and the attempt to seek historical facts is sometimes muted in the process. This case study of the 1925 Taipei Police exhibition illustrates just this need to bring history back to textual analysis. Since the 1925 Taipei exhibition was unique in the way that it seems to have been the only recorded hygienic exhibition initiated by the police in colonial Taiwan, the questions I will ask include arts and culture of the Taishō period (such as music, movies, radio, advertisements, and leisure entertainment), the supporting groups which helped or donated the displayed items, and the makeup of the “old Taiwan hands” (mainly, the police staff and the range of the social networking). Ultimately, I am interested in how Imperial Japan managed to produce its colonial knowledge about Taiwan.

2) Takeshi Soyama, Kyushu Sangyo University

Tourism under Japan’s Colonial Rule in Taiwan: From the Perspectives of Privilege,

Exclusion, Assimilation and Resistance

Japan’s colonial rule in Taiwan caused Japanese cultural concessions in Taiwan. For the Japanese who lived in Taiwan, Taiwan was an extension of the Japanese mainland, and of course, this was also true for the Taiwanese and native Taiwanese. This concept of an extension of the Japanese mainland was categorized into two types. One type was privileged spaces for Japanese people, such as Japanese-style hot springs and inns. The general Taiwanese population tended to be excluded from these attractions that had Japanese cultural characteristics. Elementary school excursions were the only opportunity for access to such places. At the time, elementary schools for Taiwanese children were to assimilate children into Japanese culture. These facilities for assimilation, such as elementary schools and shrines, constituted the second type of extension of the Japanese mainland. In 1937, when the Sino-Japanese War broke out, the Governor-General of Taiwan began to force the Taiwanese to visit and worship at Japanese shrines. In the meantime, the Taiwanese urged the Governor-General Railroad Section to conspiratorially conceal their “joss house” (Chinese folk temple) tours under the disguise of Japanese shrine tours. This situation shows that assimilation and compulsion were cleverly transformed into resistance in the context of colonialism and tourism.

3) Paul Barclay, Lafayette College

Ethnic Tourism, Wartime Surveillance and Public Relations: The Taiwan Photography of

Harrison Forman

On April 1, 1938, the photo journalist Harrison Forman began a tour of Taiwan. Forman’s visit came at a nadir in U.S.-Japanese relations, just after the Nanjing massacres. Although only a few photographs from Forman’s excursion were published, they provide, in conjunction with his unpublished diary and over sixty archived photographic negatives, a telling example of how Japanese officials and merchants utilized the infrastructure of tourism to manage the image of Japanese empire abroad. The great majority of Forman’s images depicted Taiwan Indigenous Peoples, who constituted less that 2% of Taiwan’s population. In general, cameras were tightly regulated and photography discouraged on the home islands and in Taiwan. Nonetheless, the colonial state encouraged the production and dissemination of photographs of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples. Pamphlets, postcards, and illustrated books were readily available at train stations, small shops, and the tourist bureau and freely distributed to foreign guests. This paper asks why Taiwan Indigenous Peoples were treated as the privileged face of Taiwan in the 1930s, while previously they had symbolized the failure of the government general to govern the island. I argue that image-conscious officials and thrill-seeking Westerners found common ground on guided tours to model villages in the “Aborigine Territory.” There, visitors recorded impressions of an orderly yet exotic colony while police officers monitored their movements on easily patrolled interior routes. In the bargain, visitors were diverted from Taiwan’s military installations and other vistas deemed embarrassing or sensitive by the colonial government.

Discussant: Robert Eskildsen, J.F. Oberlin University

Visualizing Asia in the Modern World

I participated in a wonderful conference held at Harvard under the auspices of the Visualizing Cultures project hosted by MIT. From the conference website:

“The Visualizing Cultures project at M.I.T. and the following programs at Harvard: Asia Center, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Korea Institute, and the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies are pleased to announce an academic conference focused on the relationship between visual imagery and social change in modern Asia entitled, “Visualizing Asia in the Modern World.” This will be the second in a series of academic conferences devoted to “image-driven scholarship” and teaching about Asia in the modern world.

We have selected scholars of history, art history, history of photography, and history of technology specializing in China, Korea, Japan, United States, and Europe to discuss how to integrate visual and textual media in research and teaching, using to the fullest the opportunities presented by the new technologies and the use of the internet as a publishing platform.”

The conference program has an outstanding list of participants with a fascinating diversity of projects that utilize original and revealing but hitherto largely inaccessible visual resources some of which may be suitable for further development as Visualizing Cultures units.”

Joint Conference of the Association for Asian Studies & International Convention of Asia Scholars

March 31-April 3, 2011, Honolulu Hawai’i (Hawai’i Convention Center)

March 31-April 3, 2011, Honolulu Hawai’i (Hawai’i Convention Center)

Statue in front of the Convention Center

This was a great conference not only for the weather and beautiful surroundings, but also for the experience of participating on a panel with so many learned scholars, who are also wonderful colleagues. Here’s our panel:

Session 300: Behind and Beyond the Lens: Photography in Imperial Japan, 1896-1945

Organizer: Paul D. Barclay, Lafayette College, USA

Chair: Laura Hein, Northwestern University, USA

Discussant: Laura Hein, Northwestern University, USA

This panel examines photography in its multiple roles as instrument, beneficiary, and victim of empire. Specifically, the papers consider conquest photography in Taiwan (1890s), commercial photography in Korea (1910s-1930s), a newsreel photographer in China and Taiwan (1930s), and art photography during the Fifteen Year War (1930s and 1940s). As these case studies demonstrate, photography surely aestheticized violence, obfuscated power relations, and pandered to voyeurism to make empire emotionally plausible, even attractive. At the same time, we argue that the relationship between the gun and the camera in imperial Japan could be quite oblique, if not troubled. By considering imperial photography as a dynamic enterprise, engaged in by amateurs, professionals, and artists under varied technological and political constraints, we draw attention to discontinuities and dead ends. Though camp followers in 1890s Taiwan were urged to push the medium’s limits as an instrument of mobilization, for example, the state thwarted photographic engagement with war in the 1940s. Moreover, we argue that specific material forms were suited to different kinds of ideological work. While photographs of carnage in Nanjing and Wuhan filled commemorative albums, postcards and glossy brochures retailed images of exotic and contented fellow Asians. For all of its diversity, however, Japanese imperial photography produced a singular cumulative effect. Decades of variation upon a limited number of themes, the incessant reproduction of a pool of stock images, and the wavering support of an overweening state overdetermined imperial Japanese photography’s exhaustion as a vital force by the end of its 50-year career.

Colonial Itineraries: Japanese “Conquest Photography” in Taiwan, 1896-1899

Joseph R. Allen, University of Minnesota, USA

My paper explores early photographic production by the Japanese colonists in Taiwan as manifested in two halftone printed albums (shashinchō), dating from 1896 and 1899. I argue that the first of these albums, that documenting the military campaign to conquer the island in 1895, established a general structural and thematic shape for later albums, including for the travel guide seen in the second album. In part, this was in the photographic trope of “encampment.” Not only did this early “conquest narrative” inform later albums, it also offered a general heuristic model by which the island came to be known to both the colonizing power and the colonized subject. The island was construed as an entity to be known as an itinerary, not as a residence. Those early models continued to inform photographic constructions of Taiwan throughout the colonial and even into the postcolonial period, contributing to the island’s ongoing state of conditionality—that is, its social reality always being construed as dependent on another cultural agent.

Romancing the “Conquered Other” in the Korean Peninsula: Travel Myths, Images, and the Imperial Tourist Gaze

Hyung I Pai, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

Visages of dancing courtesans and white-robed peasants framed by decaying ruins of pagodas, temples, and palaces are the most recognized tourist images representing the time-less beauty of Korea’s cultural landscape. This study traces the colonial origins of travel photography, postcards, and guidebooks mass produced by Imperial Japan’s travel industry when they expanded into the newly acquired colonies in Korea and Manchuria in the early twentieth century. Following decisive military victories in the Sino-Japanese (1895) and Russo-Japanese War ( 1905), both public and private, large and small operators from international steamship liners, Japan Tourist Bureau (JTB), the Korea Branch of the Japan Imperial Government Railways Co., South Manchuria Railways Co. and local Japanese settlers’ owned businesses (trams, taxi cos. station hotels, hot springs inns, photographic studios, newspapers, department stores, geisha houses) in colonized cities and towns worked together to lure the growing numbers of colonialists, leisure tourists, students, soldiers, and businessmen to purchase round-trip packaged tours via Japan, Korea and Manchuria (Naichi). This paper analyzes how geo-political factors, aesthetic preferences as well as commercial agendas have determined the selections process of a handful of highly romanticized and exoticized ‘stock images’ representing ‘Koreana’ targeting a world audience for more than century.

When a Thousand Words aren’t Worth a Single Picture: Harrison Forman, The China War and Propaganda by Misdirection

Paul D. Barclay, Lafayette College, USA

This paper analyzes the uniquely detailed documentation left behind by newsreel photographer Harrison Forman regarding conditions for photographers in 1938 Taiwan. It attempts to explain how an otherwise enterprising investigative reporter became an unwitting mouthpiece for Japanese imperialists. For despite the damning observations recorded in his diary, Forman published a sympathetic account of the Government General’s work in Taiwan. Photography as a medium, I argue, tipped the balance. At the height of the second Sino-Japanese War, police restrictions on the movement of photographers operated in tandem with profligate image distribution. By shunting foreigners off to model villages in the interior and providing lavish hospitality in resorts, as well as numerous photo-opportunities, ever-present police minders helped recast Japanese colonial rule as a civilizing mission vis-à-vis Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples. Forman returned to America in possession of an ostensibly eye-witness photographic record of Indigenous Taiwanese customs and manners, buttressed by officially distributed photographs of Japan’s struggles to stamp out headhunting in the recent past. This thematically consistent visual record simply overpowered the doubt-ridden scribbles in Forman’s notebook. Not only was Taiwan’s role in the war on China thus obscured, but repressive policies in urban Taiwan were pushed to the background.

A War Without Pictures: Photography’s Curious Position in Wartime Japan

Julia Adeney Thomas, University of Notre Dame, USA

Between 1937 and 1945, Japan’s government and the military used almost every imaginable means to mobilize the nation behind the conquest of Asia. Technologically capable and aesthetically astute, Japanese photographers also sought to inspire public support for imperialism, and yet, as I will argue, photography never galvanized the nation. This paper raises two questions. First, why did photography not play a bigger role in the Japanese war effort, especially given the culture’s sophisticated understanding of the visual arts? In comparison with America and Europe, there are few canonical pictures of Japan’s struggle, sacrifice, victories and defeats during the years of fighting. The magazines produced for the domestic market were drab compared with the glossy, glorifying publications produced for the non-Japanese market. Aesthetic experimentation, rather than being harnessed to energize the war effort, was discouraged. In short, what does it tell us that Japan’s war was, in essence, a modern war where photography played a surprisingly limited role? My second question follows on from the first. Is photography the same the world over as many photography theorists insist? If photographs in wartime Japan played a different role than they did in other militarized nations, it shows, I argue, that this “universal technology” is far from universal. I will demonstrate how social and ideological conditions in Japan constructed a distinct place for the photographic image in the 1940s.

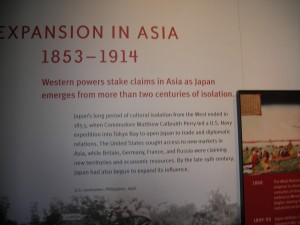

I also made my first visit to the Pearl Harbor historic sites run by the national park service. I visited the history museums attached to the USS Arizona memorial, also known as the “WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument.”

The historic sites include the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park, the Battleship Missouri Memorial, and the Pacific Aviation Museum. www.pearlharborhistoricsites.org

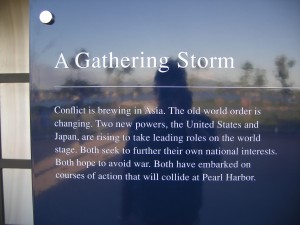

Of particular interest to me was the historical framing of the attack at the exhibit. The “sneak attack” idea has been considerably tempered by a much broader analysis of twentieth century history. In essence, as the gateway plaque below indicates, the attacks were prefaced by a century of Pacific expansion by the U.S. and Japan (1853-1941). This longer view is more consonant with that put forth by serious scholars of Japanese history, who try to understand how a more-or-less “normal” industrialized power (for the time) would embark on such a seemingly self-destructive course. Interestingly, I bumped into a historian on the shuttle boat to the memorial who had consulted for the museum as a Japanese expert. This historian suggested that the initial drafts of the textual component of the museum were in dire need of such expertise. On the whole, I think the park service did a creditable job on this museum.

“A Gathering Storm” is different than a “Day that will live in Infamy”

“A Gathering Storm” is different than a “Day that will live in Infamy”

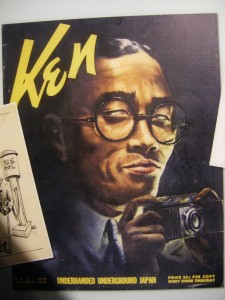

But the story of Yoshikawa Takeo, the spy who sent photographic information about Oahu (where Pearl Harbor is located) to Japan still gets pride of place.

But the story of Yoshikawa Takeo, the spy who sent photographic information about Oahu (where Pearl Harbor is located) to Japan still gets pride of place.

U.S. pop culture from the 1930s. Perhaps a “clever” people, Japanese were not considered by many to be capable of standing toe-to-toe with a the U.S. Navy in a real war. A classic case of misunderestimation.

On this poster, European activities in the Pacific are aggrandizing, while the American presence is characterized as a “search for markets.” And yet, a picture from the Philippines 1898, site of a bloodily aggressive U.S. territorial conquest, is affixed below the ambiguous captioning. Certainly an example of exhibit by committee. On the one hand, the United States is not the same kind of imperialist aggressor as the Europeans and Japanese, but at the same time, it is in global competition for resources, markets and territories. And so it goes.

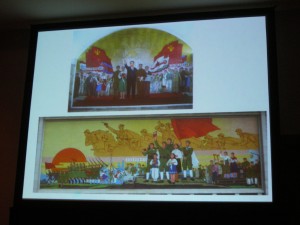

North Korean Art

At a joint Conference of the International Convention of Asia Scholars and the Association of Asian Studies in Honolulu, Hawai’i (March 31-April 3 2011), I attended a well organized and researched panel (session 600) titled “Picturing National Narratives of North Korea”. From a talk by Professor Koen De Ceuster of Leiden University, I composed this list of websites for North Korean art, which should be of use to members of the Lafayette course “Interconnections in Northeast Asia.” If you see this list and take it as an endorsement of the government of North Korea, please keep surfing and send your comments to someone else, thanks.

Mansudae Art Studio (North Korea)

Nord Korean Hidden Treasures Revealed (Lithuania)

Fine Art from DPR Korea (London)

Pyongyang Painters.com (Commercial)

Some issues raised during the panel:

North Korean art is not studied or collected in the same way that art by South Koreans, or from most other parts of the world, might be. It is clearly branded “North Korean” instead of by individual artist. Access issues, politics, and the expectations of viewers/collectors have resulted in an international exhibition complex that is marked by a lack of clearly defined collection criteria–i.e., collections in even the best museums are built opportunistically and have a patchy quality about them.

The emphasis on North Korean art as Propaganda or as socialist-realist kitsch has obscured the fact that North Korea does have artists who are not only highly skilled, but who delight in their craft. In North Korea, the craft entails celebrations of the regime and its history, but at the same time portraiture, landscapes and other genres give rein to other artistic intentions. And it is the view of the art from the artists’ perspective that is missing in international scholarship and exhibitions about North Korean art. It may well be that the sharp distinction many make between propaganda and art is not made at all by these artists, and thus may not be the best optic through which to view such art. In sum, the state of scholarly knowledge regarding North Korean art is still rudimentary, largely for political reasons beyond the control of curators, scholars and collectors, but also for ideological reasons having to do with what outsiders “need” from North Korea to shore up their own notions of normalcy, freedom, and individualism (this last point shades into my own gloss on the panel: please don’t hold panelists listed in the link responsible for this statement).

A short discussion and slide show with Nick Bonner, and highly regarded (by scholars) art collector, author and exhibitor.

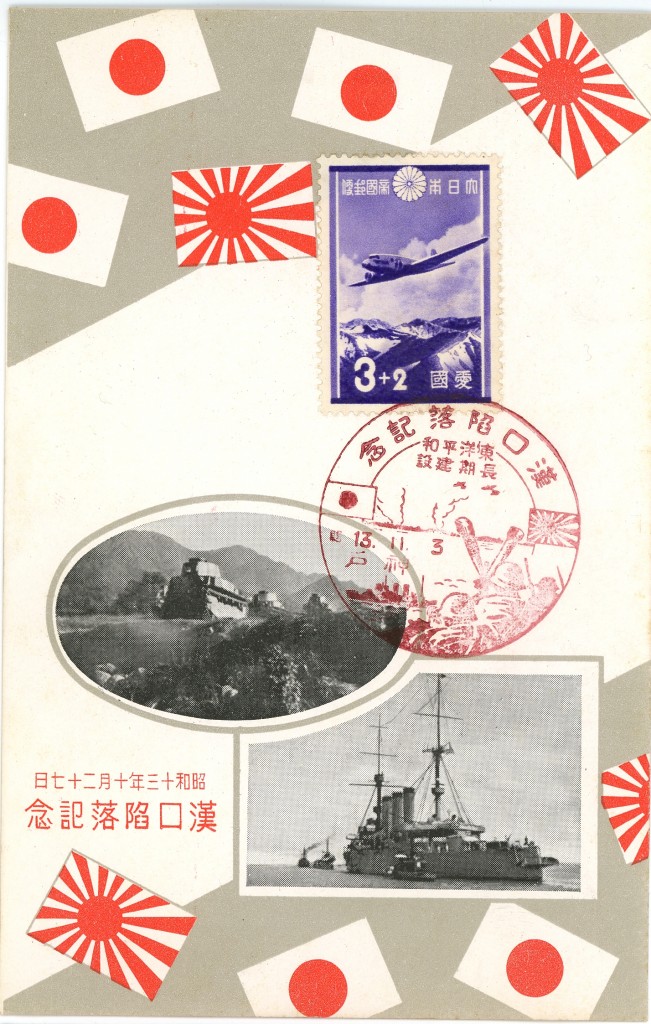

Imperial Calendar(s)

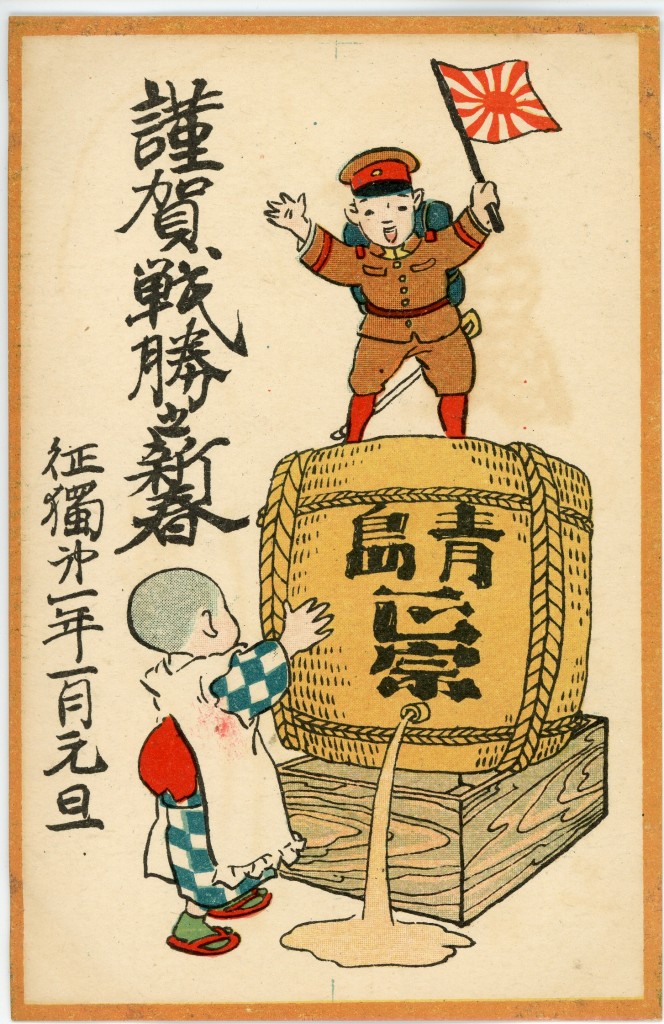

Postcards commemorating milestones in Japanese imperial rule in China. These images and captions reveal that almost any action that aggrandized Japanese empire in the early twentieth century was deemed worthy of serial commemoration by postcard manufacturers and Japanese consumers. What was/is the significance of this proclivity, and the form it took? Coming soon from the East Asia Image Collections at Skillman Library, Special Collections

http://digital.lafayette.edu/collections/eastasia

“The First New Year after the Conquest of Germany.” (Qingdao)

“The First New Year after the Conquest of Germany.” (Qingdao)

“Year 3 of the outbreak of the “Manchurian Incident” September 18th [1931]

“Year 3 of the outbreak of the “Manchurian Incident” September 18th [1931]

The Manchu Emperor’s Imperial Visit to Tokyo April 6, 1935

The Manchu Emperor’s Imperial Visit to Tokyo April 6, 1935

“3d Year of the China Incident Poster: July 7 [1937]”

“3d Year of the China Incident Poster: July 7 [1937]”