Embodied Life of the Mind, October 2016: #amwriting

Writing this book has been a very different experience from writing my first, and I’ve found myself reflecting on the differences and the possible reasons behind them. I may very well think differently, but as an embodied mind, I can only do that thinking in time and space, so it’s worth considering how my engagement with time and space makes something like a book happen.

One huge difference is, of course, institutional: the first book started life as a dissertation, then went through considerable expansion (and in some cases, contraction) and revision to become Epic in American Culture, Settlement to Reconstruction. This new project, The Hymnal Before the Notes: A History of Reading and Practice, had no programmatic starting point—I just had to write it if I was going to have a book, that’s all.

The first book was organized around the academic calendar, on quarters, in particular: rough draft of a chapter per quarter for five quarters (counting the intro as a quarter), then a few quarters for revisions. Once I started at Lafayette, that rhythm was much more punctuated as I adjusted to teaching and service work alongside my research. All the while, it was a matter of taking notes in Word, bashing out drafts in Word, revising in hard copy, and typing in revisions in Word. As far as writing technology goes, it was fairly typical and not very imaginative.

Then I started considering how to write the next book. I had become a fountain pen hobbyist toward the end of the process with Epic, and while the research for Hymnal began in earnest in 2010, I didn’t start trying to draft major pieces of it until 2012, and then it was only for articles—which I wrote in Word. By the time I was thinking seriously about book chapters, it was 2014, and I had spent most of the previous two years doing little writing beyond the workaday writing of a college professor (emails, grading, course materials, more emails) and journaling with a fountain pen. I had started taking notes for teaching with a pen in 2011, and that has now become something of a habit. In fact, I miss having that near-daily, quick-visit writing as I shaped the plans for my classes, now that I’m on my second year of research leave. So I made the decision that this new book would be composed longhand.

My primary equipment for this task has been blank notebooks from Wrapped (who, sadly, don’t make them anymore) and a Pilot Custom 74 from Goulet Pens with Iroshizuku Asa-Gao (morning glory) ink. The materials were a bit of an investment, but it’s been well worth it. I wanted a relatively lightweight, full-size pen with a high ink capacity and a gold nib, my ideal recipe for long writing sessions. And I wanted a distinctive ink color that I would love looking at for the months it would take to draft this book. The high ink capacity means I don’t have to refill all the time, and the gold nib acts like a shock absorber, keeping the writing feeling as smooth as possible. Brian Goulet has raved about this pen for years, and since it was available in purple, I decided it was definitely the pen for me. The ink has been lovely, too. Taking this amount of care and investment with my writing tools has made this book a richly aesthetic experience in ways that the first book wasn’t. It’s also helped it feel more sacred, a practice with its own space I consciously step into as I prepare to write.

Some more profound ways in which the writing experience has changed were also intentional: I wanted to get away from the screen, the Internet, my notes (still taken on computer for copy-and-paste and search uses), and whatever else a computer/keyboard setup might involve that could distract me. There’s nothing like the “oh, I need to look up that date” thought to drag out a writing session. And this new book was not going to be an exhaustive treatise on hymnbooks, but a series of narrative-driven chapters meant to evoke the reading culture that revolved around these objects in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, so sticking to the story was paramount. If I couldn’t recall a date or a name or a number, I’d just make a note in brackets and keep going. I write slower than I type, so this also gave me a chance to shape my thoughts with a bit more nuance even as I kept a steady rhythm going. The result was that drafting this book has often felt a bit like walking, and walking sessions have naturally integrated with my writing sessions.

At home, I drafted in the libraries at Lafayette, at my college office, and in my home study. Since moving to Worcester, I’ve had to seek out new writing havens, starting with my bedroom and the sun room in our rental house—I don’t have a dedicated study there, so these are more for when the family isn’t home. I have a fetchingly Spartan study carrel at the American Antiquarian Society (exposed brick, a heating pipe, no windows), but no pens are allowed in the study areas, so I’ve explored the area for good writing nooks. When the weather’s good (and it’s been marvelous many days recently), I’d go out to here:

Or here:

These are both a mile or less from home. When the weather’s been not as good, the walks get longer, such as here:

and here:

and here, where I basically have to drive:

Dying malls can be remarkably peaceful places to work, and both Worcester Public Library and Holy Cross’s Dinand Library have lovely study areas. I’m actually kind of in love with Dinand, and will write a followup post on that soon.

This book has been much more about sustained attention while exploring thoughts and places, finding quiet at distances of a mile or more, and watching the ink flow with my thoughts. Not coincidentally, I have loved writing this book in a way that wasn’t quite as powerful with the first one, and I have a much clearer feeling that what I’ve done is good. It’s still rough at this stage, but there’s a quiet confidence in the work I didn’t have space for when writing against a graduate fellowship clock, and then a tenure clock.

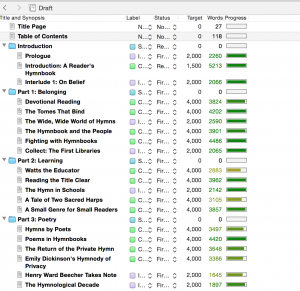

Once I drafted, I transcribed the text into Scrivener, my new word processor of choice. Its robust file-management system lets me keep all drafts and notes in a single place, while the project features let me do outlining, goal-setting, progress-tracking, and annotating in ways I couldn’t quite do with a standard word processor. I still use Word for smaller projects, but I’m hooked on Scrivener for the large-scope stuff. Doing this transcription had the added benefit of doing a first round of revising and editing as the words went on to the screen, making the draft already better than a mere one-pass draft would have afforded.

But now that the draft is done, I find I’m a bit sad. I’ll use a fountain pen to mark the hard copy, like I did with the first book, but most of the work left to be done on the book is in the screen-and-keyboard environment that I, frankly, have a lower tolerance for than I used to. And I don’t like hauling a computer on long walks like I do with a 5″x8″ notebook and a small pen roll. I may wind up doing more journaling in the mornings than I’ve been doing, simply to keep that pen-and-paper contact a part of my routine. And I think this means I’m going to have to keep writing books. In fact, I just ordered some new pens and inks for that very purpose.

I love hearing the process, Chris. Thanks for taking time to share it. I’m much faster typing and I can only write in smaller chunks of time most days, but I’m intrigued at your longhand book-writing. I’d love to hear more about the internal shifts that happened.

Thanks, Ashley! I’m hoping I can circle back to this topic with a bit more reflection soon. Trying to sort through a number of thoughts to get my blog back in gear. Thanks for reading, and for sharing the good words!