“…and if we don’t have it, you ain’t gon’ have it either, cuz we gon’ tear it up.”

~ Fannie Lou Hamer speaking on radical youth movements of the 60s

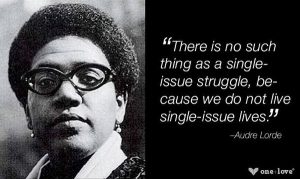

See, Fannie had the right idea – nobody is free until we’re all free. Nobody gets to be free until we’re all free. Black folk have been telling us this from the advent of this haphazard, violent project known today as the Western world. Black folk throughout history can teach us many things about liberation, but perhaps one of the most pertinent reminders is that the movement for liberation must be led by those who are most marginalized. How can white middle-class people begin to imagine the landscape of freedom when they have never known the dangers of the most treacherous social terrains? Liberation must always center those who are most dispossessed. Only they, knowing the societal boundaries of dehumanization, can restore us to a sense of humanity that is not bound up in the oppression of others. This is why intersectionality is important (and a love letter of sorts to marginalized black folks – queer, woman, trans, poor, child, elderly, undocumented, incarcerated). It reminds us to center those who are most vulnerable, a centering that not only means including more diverse narratives or theory, but DECENTERING those who occupy hegemonic power. Tokenization is not an option. Structural changes are needed to reimagine a world that is not poisoning itself with oppression. That is what decolonization looks like.

Enter: Digital Humanities.

I’m already skeptical of everything in this world, especially being of the Afropessimist school of thought that posits that this world is anti-black at its very foundation and until we grapple with that reality, we will forever be doomed to reproduce its oppression. In the first couple papers we read, I was not moved by the claims that Digital Humanities was revolutionary, at least not in the fullest sense of the word. Revolutionary in the sense that it offered an innovative alternative to the humanities as it was understood, sure, but even the humanities (prior to DH) was struggling to decolonize. Lafayette’s faculty today, for example, is still overwhelmingly white (including the Africana Studies department). So how can a truly revolutionary DH emerge from these conditions?

Risam was right to highlight that any Digital Humanities that wants to claim relevance must organize out of a black feminist and intersectional lens. The example she gave about coding is perhaps one of the most useful. That there are groups that exist such as Black Girls Code is testament to the paucity of minoritized groups in areas of technology, particularly because the learning of code is most often only accessible to upper middle class white men. What epistemologies have been obscured, peripheralized? The plain fact is that knowledge production is inherently political and any perspective or area of study that wants to claim an apolitical posture should be examined with deep skepticism for the danger that it poses in uncritically reproducing existing oppressive social dynamics.

I also appreciate Risam’s argument for the use of black feminism in praxis in that she suggests that every manifestation of Digital Humanities must be guided by the specificity (or locality) of its given context, not by monolithic, hegemonic methodologies. I thought about the places that most need the Digital Humanities, like Jamaica, where so much of our heritage is sitting at a precarious place, always at risk of erasure, but I struggled to imagine a DH that was uniquely Jamaican or Caribbean. Still, It’s a struggle on which we must embark if we are to have a truly liberatory, revolutionary DH instead of one that reifies the Global North’s dominance. Intersectionality does not present the risk of limiting the field, as Risam posited, but rather it extends the field into a new range of possibilities for exploration, like Dr Meredith Clark’s interesting work on Black Twitter (https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/04/the-truth-about-black-twitter/390120/)

I look forward to a DH committed to centering the Global South, people of color, women, the working class, queer and trans folk and others who have been othered. Or else we gon’ have to tear it up.