Early America and the Digital Humanities: Some Modest Proposals

To kick off this blog, I’ve decided to return to a piece I worked on some six months ago as a paper for Jim Egan’s Society of Early Americanists panel on early America and the digital humanities. The title of my paper was: “Placing Criticism in Realms of Reading and Visualization.” As is my usual m.o., I gave the paper as a notes-based talk rather than as a formal essay to read, and this is the first time I’ve worked out my talk in fully-paragraphed form.

Let me start with a few observations about the place of DH in a setting like the SEA conference. Compared to the evidence-and-argument basis of the standard literature/history conference paper, DH presentations at venues like the SEA tend to sound like either thinking out loud (what will the future hold?) or a commercial (look what I made and how it can work for you!). It’s hard for the conference’s core membership to find the evidence, the analytical work, the critical conversation, or the rhetorical payoff in these kinds of presentations.

And yet the inellectual work behind building a tool or an archive is palpable to those who have done such a project. The trick is to make that work visible in a rhetorically meaningful way for those who use more theory- or archive-based methods—making it easier to understand how much theory and archival work goes into DH projects on the early Americas.

This need for translation points to an important absence in the traditional paper: the work of researching, transcribing, searching, and browsing go unnoticed in the course of making a scholarly argument. To find a sentence like:

I stumbled on [insert article here] while looking through a set of newspapers from 1822, and my next thought was to search for instances of [insert keyword here] using the Early American Imprints database.

would be a novel, if not bizarre, moment for a conference audience. We don’t often explain or describe our methods, our epiphanies, or our sources.

Should anything be done about this? And if so, what? I’d like to offer three modest proposals, followed by a coda based on my own DH research on an early-republic Pennsylvania library.

First, early Americanists should include methods sections in their essays. This standard component of papers in the natural sciences as well as several social sciences would make much more visible and useful the work that we do in any approach, digital or otherwise. Early Americanists rely on a hodgepodge of databases, printed scholarship, and archives in a wide range of locations, institution types, conservation and cataloging resources, etc. Not revealing how or where we find a document might save a writer some work (and occasional embarrassment—do I really want to admit I used Google Books to find that Franklin quotation?). But it ultimately does all of us a disservice, as it masks the work we have actually done, it makes locating sources more difficult for others, and it makes the craft of research more occult to newcomers in the field. If we want to say that digital resources are democratizing access to research materials, we need to relate best practices for working with those materials to a larger audience than those personally apprenticed to the most renowned scholars in the field.

Second, we need to acknowledge how much the digital already undergirds what we do as scholars. Many early Americanists no doubt share my experience of having URLs and other cues that an online version of a text was my source stripped from bibliographies prior to publication. While this is by no means a universal experience, it’s common enough that some scholars, such as myself, forget even to indicate whether a source was in digital or hard-copy form. The richness of our field’s media ecology is often invisible, potentially making “born digital” methods seem more foreign than they may in fact be.

Third, we need to take a hard look at what constitutes an argument in our field. To me, this means not only considering how tools and archives are arguments (and I would contend that they are) but also how things like editions, anthologies, and textbooks are also significant arguments. It doesn’t seem entirely coincidental that the MLA’s guidelines for evaluating digital scholarship appear directly below the guidelines for preparing scholarly editions on the MLA website. We don’t have a rhetorically effective template for presenting editions at a conference either, though Tom Hallock’s presentation on editing William Bartram at the 2011 SEA conference could very well serve as a model in that genre—opinionated, evidence-based, and focused on a conclusion while engaging explaining the work of editing. Integrating DH work into early American studies may change much more than merely adding the digital to our list of methodologies.

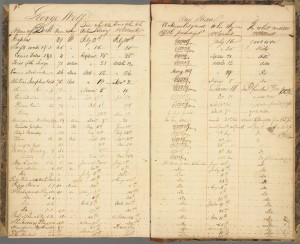

A page of George Wolf’s account, of interest to political historians as well as historians of reading: Wolf later became governor of Pennsylvania.

To give some idea of how I think this third point might play out, I’ll talk about the theory of reading I’m working with in developing a database of loan records from the Easton Library Company (1811-1862). One of the great difficulties in the history of reading, as Leah Price and others have pointed out, is that capturing the act of reading from the past is nearly impossible. We can examine sales records, marginalia, loan records, patterns of wear on books, and other data to determine how a book was acquired, transferred, handled, talked back to—but what about reading itself?

As I’m working with loan records in my project, I have asked myself these questions while looking at scans of two-page spreads covered in 19th-century handwriting. One answer that I’ve come to work with is that reading is, particularly in a social setting like a shareholding library, an aspirational act. We buy and check out books we want to read, or be known to read; at a certain point, whether we read the words on all the pages or not is beside the point. While determining individual motives for reading, social patterns surrounding certain titles, authors, or genres can offer insight into what the community was interested in.

Another intervention I hope to make with this project is that we can tell different kinds of stories about reading if we follow the books or the readers. The search capabilities of a database allow for both. Did a certain title circulate through a neighborhood or a church congregation or a circle of business associates? What did library users tend to choose after returning, say, Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia or Amelia Opie’s Tales? Were users more loyal to specific genres, or formats, or authors, or subject matter? Is there a pattern to which books were “read to death,” or turned up missing, or were overdue? Some of these questions are helpful for the light they shed on relationships between books, others about the behavior of users—often both. A database such as this can thus help to bring together the text-based interests of literary scholars and the behavior-based interests of historians.

This last observation points to another key intervention into the history of reading: this database not only allows for pursuing questions from several disciplinary perspectives, it also serves as the occasion for scholars in various fields to encounter and respond to each other’s work. One potential feature of the database’s website in the future is a bibliography of scholarship drawing on the database, possibly even open-access copies of scholarship available at the site. Interpretation, aggregation, and computation all grow much closer in this kind of environment, meaning that the history of reading, at least in this instance, can become more interdisciplinary than it already is by virtue of linking scholarship to its sources.

Much of this will be old news or even naivety to veteran DHers, and it may very well meet with skepticism from early Americanists. What I hope is that we can expand our dialogue about the future of a new methodology and of an older (though still fairly emergent) research field in ways that bring benefits to both.