What Is the Bay Psalm Book, Anyway?

I’m on a roll now–two posts in a week! I couldn’t pass up some big book-geek news: the auctioning of the Bay Psalm Book for $14.2M last week, making it the most expensive printed book ever purchased. (Bill Gates shelled out $30M for a Leonardo Da Vinci notebook known as the Codex Hammer–bet the auctioneer loved that one.) Even if the gavel price of $12.5M fell short of the speculations that the book would fetch between $15M and $30M, it’s an extraordinarily expensive book, and therefore more alluring than it was a year ago. The hype surrounding the book has led to a storm of blogging, news coverage, and even gatherings such as the American Antiquarian Society‘s pizza party to watch the live video of the Sotheby’s auction. I’ve been fascinated and a bit bemused by the hype, and I wanted to share a few observations about this book from my perspective as a scholar of hymnbooks.

Most of the bloggers I’ve read have included two points in their writing: the book appeared twenty years after the Mayflower sailed, and the poetry is dreadful. These are both quite true, but they distort what the book is about; these points set up the narrative of a flawed but ancient founding text tied to the very earliest wafts of the winds of American freedom. It has been said that the Puritans who produced the book hated the King James Bible as well as the Book of Common Prayer; that this book was an early hymnal; that the book is a monument in the history of printing. Let me offer some alternatives.

The key date for the Bay Psalm Book’s backstory is not 1621 but 1630, the year John Winthrop, Simon and Anne Bradstreet, and other Puritans arrived in Boston Harbor on the Arbella. These people had been part of the Church of England in one way or another but were on their way to what would become congregationalism in New England. The Pilgrims, who had already been in Plymouth for nearly a decade, were Separatists who wanted nothing to do with the Church of England, and who wanted nothing more than to be left alone to worship their God, using the Ainsworth Psalter as their preferred liturgical text.

The reason why everyone used psalters in these early New England settlements was because they, like the Church of England and the Huguenots in France, were Calvinists. Calvin had taught that the only texts appropriate for corporate worship were inspired texts, I.e., from the Bible. Hymns of human origin were used for private and family devotions but not for church services; that fact would not change in most churches until the Great Awakening and the Methodist movement in the mid- to late-18th century. You had to have psalms if you were going to sing in church, and Calvin had also taught that Christians should be singing Christians.

Thus the Puritans in Boston needed a psalter. Their neighbors’ Ainsworth books were already considered creaky and the psalter used in the Church of England, Sternhold & Hopkins, was at least as bad. Puritans, though many had an interest in poetry (remember Anne Bradstreet, married to a lieutenant government of Massachusetts Bay), were not looking for aesthetic value, however. They wanted to sing the Word of God, as closely to the spirit and sense of the original Hebrew as possible. The Authorized Version of the Bible, usually called the King James Version, had been around for a generation, and was widely accepted among Puritans on both sides of the Atlantic as a highly literate and literal translation. The problem was you couldn’t sing it: the Psalms had been rendered into quasi-metrical prose that wouldn’t fit any tunes that a group of English folks would be expected to know. That meant a metrical version was needed, and the versions available (Ainsworth, Sternhold & Hopkins, and a few others) did not accurately reflect the original. Thus the project of the Bay Psalm Book was born.

It’s probably fair to say that the book is more a feat of translation than it is of printing. The book was produced to supply a public need, not (primarily) to make a cultural statement. While the printing job was not a small one–the book used twelve sheets of paper per copy at a time when ten sheets was considered a big project–it was made to be carried and used, not admired. Those sheets were folded down into a format known as duodecimo, in which one sheet would be folded and cut to make twelve leaves or twenty-four pages. That meant it would likely be more at home in a pocket or on a small table than in a bookcase.

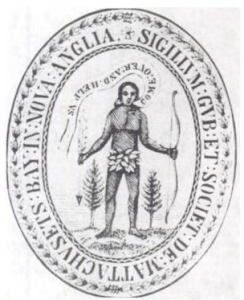

The true monument of early New England printing came decades later in John Eliot’s Algonquin translation of the Bible, printed from 1661 to 1663. Massachusetts Bay, unlike Separatist Plymouth, was founded as a missionary colony, meant to raise capital for the crown and convert the natives. The seal for the colony depicted an Indian saying, “Come over here and help us,” a reference to the dream St. Paul has that convinces him to start preaching to the Gentiles. Eliot and a team of Wampanoag converts spent over eight years completing their translation, and since the English Bible could only be printed by royal contract, it would be the only Bible printed on a New England press until the Revolution. While the analogy might be a bit of a stretch, it could be said that the Bay Psalm Book was to the Eliot Bible what the indulgences Gutenberg printed in single sheets were to his Bible project–smaller, more utilitarian jobs that funded and slowed grander undertakings.

One of the reasons this book is so much rarer than the Gutenberg Bible, Shakespeare’s First Folio, and many other prestige collector’s books is that it was actually used, at least weekly in most cases, nearly daily in many homes. Over time, with exposure to the elements, hand oils, clumsy handlers, mold, and fire, many copies simply disappeared. This often happens with the most popular books: there is no surviving first edition of the New England Primer or John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, while the first edition of Isaac Watts’s Hymns, long thought destroyed, is now known in three copies worldwide. The Bay Psalm Book became precious not just because it was first, but because it was read nearly to death.

Many of the destroyed copies may have become something else over time: wallpaper, wrapping paper, toilet paper, paper for testing quill pens, starting fires, or binding other books (paper was scarce in early America, and has always been the most expensive part of book production). And now the Old South Church‘s second copy of the Bay Psalm Book has become something else as well. Buyer David Rubenstein has already announced that he intends to tour the book at major libraries before arranging for a long-term loan at one of them, ensuring that the public will have access to a book highlighted as a cultural treasure. The book has become a relic that people can make pilgrimages to, whether for religious reasons or not. And, as Casey N. Cep has pointed out, the book has become repairs to an aging building, food for the hungry, aid for those suffering in Boston, Haiyan, and elsewhere. The Bay Psalm Book began as a liturgical project meant to galvanize the pastoral ministry of a new colony; now, after being superseded by generations of psalters and hymnals, it has transformed back into the means for pastoral ministry, through exchange value created by being nearly consumed by its initial success.