Introduction:

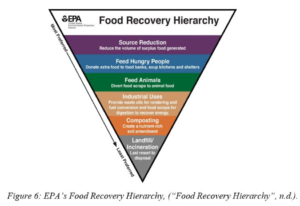

The reason we are concerned with diverting food waste from landfills is because a surplus of food is being generated in the first place, and not enough of leftover food is donated to populations in need. Composting is the last resort for recovering food waste before it is sent to landfills where it creates methane, which is a potent greenhouse gas. (“Food Recovery Hierarchy”, n.d.). Lafayette College’s focus on diversion rates comes from the Climate Action Plan 2.0. The school supported the implementation of a CAP for two main reasons. First, the CAP reduces Lafayette’s contributions to the devastating effects of climate change. Second, in a society where environmentalism has become increasingly valued, having a CAP can improve the standing of the school and make it more desirable to prospective college students.

Context 1: Consumerism & Other Reasons Food Waste is Bad

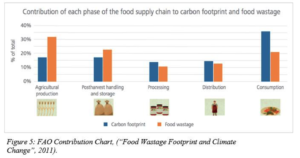

Without consumerism, we would not have to worry about diversion rates in the first place. Yet, in high income countries, we see patterns of wasteful food distribution and consumption. As the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations points out in Figure 5, on a global scale, consumption is responsible for the largest carbon footprint of the five steps of the food supply chain: agricultural production, handling and storage, processing, distribution, and consumption (“Food Wastage Footprint and Climate Change”, 2011). Most carbon emissions come from the final step of the food supply chain because “harvesting, transportation and processing accumulates additional greenhouse gases along the supply chain,” (“Food Wastage Footprint and Climate Change”, 2011). Therefore, before we increase diversion rates, it would be ideal to reduce the amount of food going to waste from individuals’ plates as this can reduce the amount of money and energy wasted along the food supply chain. Furthermore, reducing the amount of food waste from industrialized countries could lead to improved distribution of food to countries that need it (“Reduce Wasted Food by Feeding Hungry People”, n.d.).

These methods for dealing with food waste are outlined in the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy as shown in Figure 6. In summary, the hierarchy ranks methods for dealing with excess food from most preferred to least preferred. The most preferred method is reducing the amount of food being distributed, as this would in turn reduce the energy and money wasted on food production (“Food Recovery Hierarchy, n.d.). Next, any food that is leftover should be donated to populations that experience food insecurity. After this, it is preferred that food waste be given to animals. If the previous options are unavailable or unable to be completed, then the next preferred method is using food scraps to generate alternative forms of energy. Composting, which is what we are focusing on, comes after industrial use as the second to last preferred option for managing food waste. The last resort would be to send food waste to landfills. This shows how low our project falls in the order of preference for dealing with surplus food. Before we resort to composting, there are better ways to deal with food waste.

Implied within the first level of the Food Recovery Hierarchy is that wasted food results in wasted energy and wasted money. Therefore, the most ideal way of dealing with food waste is to eliminate it in the first place. According to the FAO, one trillion US dollars are lost each year due to food waste. These costs are associated with the labor required to produce, handle, and distribute food as well as the resources and energy necessary to generate food (“How to Prevent Wasted Food Through Source Reduction”, n.d.). Additionally, the amount of energy wasted as a result of food waste made up 2% of the United States’ annual energy consumption as of 2010 (Cuéller and Webber, 2010). Considering this data is from nine years ago and the fact that this number was a lower bound at the time, we can assume the wasted energy from food waste is in this ballpark with increased population and pushes to reduce greenhouse gases. When dealing with food waste, it is necessary to understand the money and energy that is also wasted.

Just as much as money and energy are a concern, so is the amount of people that do not have regular access to food. Not only is food waste an issue of the environment and economy, but it is also a moral issue. While many people are disposing of edible food, populations are at the same time lacking access to food (Papargyropoulou et al, 2014). In 2017, 11.8 percent of American households “had difficulty providing enough food for all their members due to a lack of resources” (“Reduce Wasted Food by Feeding Hungry People”, n.d.). At the same time, Americans were disposing of millions of tons of food, much of which could have been redistributed to populations that are in need. Organizations such as the Food Recovery Network, of which Lafayette has a chapter, makes efforts to redistribute food from dining halls that goes uneaten to communities in need. In this case, money and energy are still used, but more food is diverted away from landfills.

While eliminating food surplus and donating to hungry populations are the ideal methods for dealing with the issue of food waste, our project is focusing on composting, which is the second to last preferred option of the Food Recovery Hierarchy. Although, we recognize that options exist for reducing food waste that are better for the environment, economy, and overall population, composting is still a useful method for dealing with food waste that could significantly help Lafayette reach its CAP goals.

Context 2: CAP- Environmental

A major goal of the Lafayette Climate Action Plan is to educate students and be a leader for reducing climate change impacts. Recently, the effects of climate change have become very apparent in many parts of the world, and colleges across the country have begun to implement climate action plans as a way of reducing the negative environmental effects that the school and their students have on their surrounding environment.

The general idea of a climate action plan is to create an inventory of all the greenhouse gas emissions generated both directly and indirectly by the college’s campus. These include fuel burned on site for heating, facilities, and maintenance vehicles, as well as emissions that come from any off site power plants that generate electricity for use on campus. One major concern with climate action plans is that they do not work as intended, however if they are implemented correctly and have long term goals and solutions, then they can be very effective in reducing the environmental impact associated with large campuses (Moore, 2018).

The Lafayette College Climate Action Plan 2.0 includes several sections such as Buildings and Facilities Energy Use, Minimize Waste, Transportation, and Curricular Integration. Each of these sections outlines the current practices on campus and how their negative effects can be mitigated to assist in reaching carbon neutrality by 2035. The section of the Climate Action Plan that our reports focuses on is the ways to minimize waste. In this section, the college has set a goal of achieving 60% diversion rates by 2035. This means that by 2035, three-fifths of the amount of waste created on campus must be diverted away from landfills. When waste breaks down in landfills, it releases methane gas, which is a greenhouse gas that is more potent than carbon dioxide. Thus, a diversion rate of 60% will help reduce Lafayette’s contribution to atmospheric methane gas. In order to get to this diversion rate, Lafayette has implemented recycling initiatives such as green move out, in addition to increasing recycling and composting around campus (“Climate-Action-Plan-2.0”, n.d.).

In 2008, Lafayette College purchased two Earth Tub Composters, which are able to handle about half of the food waste generated from one of the two major dining halls on campus. In order to increase this amount to reach the 60% diversion rate goal, the college will need to implement a larger composting program, educate students about the negative environmental effects of food waste, and encourage them to produce less food waste (“Climate-Action-Plan-2.0”, n.d.)

In 2005, a Bon Appétit manager at Saint Joseph’s College of Maine realized he could cut plate waste in half just by removing trays from dining halls (“Lafayette Dining Service’s Sustainable Practices, Sustainability, Lafayette College,” n.d.). Several years later, Lafayette caught on to this movement and removed trays from all dining halls on campus. This helped to reduce food waste as students were limited by the amount of food they could carry to the table at once. However, the two main dining halls on campus are buffet style, as shown in Figure 7, where students serve themselves. Especially at these two locations, students are inclined to take large servings so they do not need to stand in line multiple times. This is going to become an increasingly large issue as the student body continues to increase.

Context 3: CAP – School Standing

The other main reason Lafayette created and approved a Climate Action Plan was to enhance the school’s reputation and bolster its standing compared to other schools and universities. This has been a developing trend among schools and companies as the climate change issue has become more established. More organizations have pushed for environmentally related efforts because they look good to the public and may attract more customers, or students in the case of schools. The increased attention to being an environmentally conscious establishment has produced competition, especially among colleges and universities. This can be seen in almost any school ranking system nowadays. For instance, College Magazine publishes a yearly article about the top ten environmentally friendly colleges and universities (Croy, 2019). Similarly, The Princeton Review produces an annual Guide to Green Colleges that profiles 413 colleges with commitments to green practices and programs (“The Princeton Review Guide to Green Colleges: 2019 Edition Press Release”, 2019). The guide also includes a yearly list of the top 50 Green Colleges (“Top 50 Green Colleges”, n.d.). With all of this competition, it is important for Lafayette to compare its green initiatives against what other schools are doing. The rest of this section will summarize what some of the top green schools are doing, what some of the differences between these schools’ environmental goals and Lafayette’s are, and why these differences may exist.

One college that is consistently in the top ten green school rankings across a variety of publications is Colby College in Waterville, Maine. Colby College achieved carbon neutrality in 2013 and was one of the first four colleges or universities in the U.S. to do so. Colby started tracking its success in environmental sustainability with its Climate Action Plan, published in 2010. The plan called for carbon neutrality by 2015 and outlined an assortment of commitments to improve and monitor Colby’s progress to carbon neutrality. Besides becoming carbon neutral by 2015, the plan also included goals such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 41%, designing new facilities to achieve a minimum LEED silver standard, and to develop aggressive education and outreach programs (“Colby College Climate Action Plan”, 2010). For waste management and recycling, many of the initiatives for this area were already in effect before the publication of Colby’s plan. Thus, the plan does not have any specific diversion rate or recycling goals that can be compared to Lafayette’s. Nevertheless, Colby’s recycling programs and policies have been effective contributor to Colby’s environmental goals. Colby purchases 100% recycled paper products and has a RESCUE (Recycle Everything, Save Colby’s Usable Excess) program that donates and recycles clothing, furniture, appliances, and other items (“Colby College Climate Action Plan”, 2010). In terms of food waste, Colby composts over 100 tons of pre- and post-consumer waste through outsourcing and implemented tray-less dining in 2008, which saved approximately 79,000 gallons of water and 50 tons of food waste (“Sustainable Dining”, n.d.).

Another college that has traditionally performed well in green school rankings is Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Like Colby College and Lafayette College, Dickinson signed the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment in 2008. This led to the publication of Dickinson’s Climate Action Plan in 2009. The plan states a central goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2020. Dickinson’s plan has a different organization from Lafayette, though, and divides its initiatives into four main areas: purchased electricity, on-campus fuel combustion, transportation, and offsets (Sheriff, 2019). Dickinson has since then established targets and focused more on progress in these four areas. For recycling and waste management, Dickinson’s only statement is that the school is committed to reducing materials consumption, reusing materials, and recycling and composting (“Dickinson College Climate Change Action Plan”, 2009). Other than this, Dickinson does not provide a specific diversion rate goal. For its food waste program, Dickinson relies on windrow composting at its five acre college farm. As part of its Farm to Fork to Farm program, Dickinson is able to collect and compost all of its food waste. Dickinson also has an established monitoring system for tracking campus waste in its Waste Minimization Sustainability Dashboard which is updated every fiscal year (“Sustainability Dashboard: Dickinson College”, n.d.).

Compared to other schools’ Climate Action Plans, Lafayette’s CAP has fairly similar goals and milestones, but with different target years. Lafayette’s diversion rate section is much more detailed and has a specific diversion rate goal that most other schools do not have. This could be explained by two reasons. The first is that Lafayette is a highly residential school which means a large percentage of its students and faculty eat on campus. Therefore, dealing with food waste and increasing diversion rates may have more of an impact on Lafayette’s sustainability goals. Another explanation for this disparity is that other schools already have successful waste management and recycling programs in place. Among the top 50 schools for the Princeton Review’s Green Colleges rankings, every school diverts at least 50% of its waste from incinerators or solid-waste landfills (“The Princeton Review Guide to Green Colleges: 2019 Edition Press Release”, 2019), compared to Lafayette’s current 14% diversion rate. Both Dickinson and Colby, schools that are similarly residential to Lafayette, divert 100% of their pre- and post-consumer waste. Based on this overview, Lafayette has effectively defined what needs to be achieved for diversion rates. However, Lafayette could mirror some of the other colleges’ recycling practices in order to achieve the same success other schools have experienced, and to improve its environmental standing among colleges and universities.

In the next section we analyze the political context of increasing food waste diversion rates.