Introduction

Along with the environmental factors associated with reducing the amount of food waste sent to landfills, there are also many economic factors that play an important role in deciding how this food waste should be handled. In 2008, Lafayette College decided to implement a composting program on campus for educational use. The college purchased two Earth Tubs from Green Mountain Technologies, Inc. These composting Earth Tubs, along with aeration piping, temperature probes, and biofilters each cost $9,650. Additionally, Lafayette College purchased two food pulpers to be used in the two main dining halls on campus, Marquis and Upper Farinon. By using these food pulpers, we are able to reduce the volume of food waste created in the dining halls. This allows us to double the amount of food waste going into the Earth Tubs (Arthur Kney, personal communication, October 25, 2019).

If Lafayette were to send food to the landfills like it does with the remaining food waste that cannot be composted on campus, it would cost the school $80 per ton. By current estimates, each main dining hall on campus produces between 150 and 200 pounds of food waste per day (“FoodWasteCollectionEarthTubs(Upper_Plate_Waste)”, 2019). By composting on campus, the school is able to save these tipping fees at the landfill and is also able to save costs associated with purchasing compost for use at LaFarm. However, in order to operate the two Earth Tubs on campus, food waste must be collected daily from the two main dining halls and brought to the Earth Tub location in the Bushkill parking lot. Since the compost tubs are turned by hand, there are no mechanical parts that require maintenance. The Earth Tubs, besides loading and unloading, only require periodic mixing and are therefore inexpensive to operate.

When trying to decide how to grow the size of the composting program at Lafayette, it is also important to consider how these projects are funded. The two Earth Tubs that the college currently uses were paid for by grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. Future developments in the composting program must be driven by desire from students involved in on campus composting. Because composting is not a profitable investment for Lafayette, the college will only purchase composting equipment for student education or campus involvement. In order to increase the amount of food that is diverted from landfills, the school may also have to rely on donations or grants from organizations such as the EPA or DEP. Since composting is an expensive investment that does not produce a profit, it is important for the college to receive grants to be able to afford to implement such systems (Arthur Kney, personal communication, October 25, 2019).

Alternative 1: More Digesters

If Lafayette chooses to invest in a digester system to increase food waste diversion rates, then there are significant costs to consider. The two digesters considered for this alternative contain large upfront costs for the system as well as payments for periodic replacements of parts. Also, the decision would have to be made whether or not we would keep the existing composting program in addition to implementing a new in-vessel system. The Intermodal Earth Flow from Green Mountain Technologies and the Model 500 from For Solutions are both capable of diverting at least 100% of Lafayette’s current amount of food waste from landfills. However, according to a representative at Green Mountain Technologies, removing the current system would require finding a buyer as well as renting a lift gate to physically move the system because they do not buy Earth Tubs back (personal communication, December 3, 2019). Otherwise, both of the systems considered are automated; therefore, the number of student compost managers needed and overall labor costs would be reduced. With automation, though, we have to consider the cost associated with the amount of energy required to power each system.

The Intermodal Earth Flow recommended by Green Mountain Technologies has costs associated with its equipment and implementation. The cost for the Earth Flow is $60,000. This covers the shipping container as well as the automated system. The auger, which is responsible for mixing the food waste and bulking agent combination, will need to be replaced every four years, and right now it costs $1,400. Otherwise, the Intermodal Earth Flow is designed to have a long service life with little to no additional maintenance costs (“The Intermodal Earth Flow”, n.d.). Since the company is located in Washington, a shipping fee ranging from $5,000 to $6,000 will be incurred upfront. A startup fee of $7,000 will also be included in the initial cost for the Intermodal Earth Flow. The startup fee covers the cost of sending a representative from Green Mountain Technologies to Lafayette who will teach individuals responsible for composting on campus how to use the system, and they will help get the composting process started. When these costs are considered together, the Intermodal Earth Flow has an upfront cost of about $72,000. All of these prices came from a phone call with a representative at Green Mountains Technology (personal communication, November 18, 2019).

Similarly, the Model 500 from For Solutions has upfront and maintenance costs that are necessary for consideration if this option is pursued. The upfront cost for this system is $187,500. When a shipping and installment fee of less than $5,000 is considered, the upfront cost of the system comes to about $188,000. Similar to the Earth Flow, this model was designed to be sustainable, and therefore requires minimal maintenance. The only parts that will need to be considered for replacement are the motors and blades. The four motors will need to be replaced every 10-15 years, and the blades for shredding will need to be replaced every 15-20 years. Otherwise, this digester does not require a pulper to chop up food waste since it already has a shredder attached to reduce input volume, which can be seen in Figure 13 of the technical section labeled with the letter A (“For Solutions Info Sheet”, 2018). Therefore, more research is needed to figure out what to do with the pulpers if this option is chosen. All of these costs came from Nick Smith-Sebasto, founder and executive chairman of For Solutions (personal communication, November 18, 2019).

Based on the upfront costs and processing capacities of the Intermodal Earth Flow and the Model 500, we concluded that the Intermodal Earth Flow is a more viable option. While there are other costs to consider such as maintenance and labor, both systems require minimal upkeep and are automated which reduces the need for labor. In terms of digesters, the Intermodal Earth Flow is a better option because it is able to compost 45% more food waste than the Model 500 at more than one third of the cost, and arrangements do not need to be made for the pulpers.

Alternative 2: Windrow Composting

The second alternative to increase composting on campus is windrow composting at LaFarm. Windrow composting takes more land than other methods of composting such as using Earth Tubs, but a much larger amount of compost is able to be generated by this method. Lafayette College currently owns around 80 acres of land surrounding LaFarm that is rented to farmers every year. This means the college would not need to purchase extra land to compost on.

There are several other large costs associated with this type of composting however. Compost from on campus dining halls would need to be transported to the composting area at LaFarm daily. In order to accomplish this effectively, there would need to be a dedicated truck for use by the student compost workers to transfer the food waste to LaFarm. The student compost workers already work for Lafayette, so the labor cost would not increase if food waste had to be transported to LaFarm, but it would take about two hours of their shift each day to collect compost and drive it off campus. Once the compost is piled in rows at the composting site, it is necessary to turn the piles every few weeks to several months depending on the internal temperature of the pile and to incorporate oxygen into the pile (Richard, 1995). This is the largest cost associated with windrow composting as the school would need to purchase a tractor and a turning implement. Based on similar equipment to Dickinson College’s windrow system, it is estimated that the combined cost of the tractor and turning implement could be as much as $65,000 plus yearly maintenance. The time spent turning the compost piles would also require several hours of labor to complete (Matt Steiman, personal communication, November 20, 2019).

One major benefit of windrow composting is the increased volume it can handle. This would allow the college to compost all of the food waste from every dining hall, and all the debris from campus grounds maintenance as well. This would reduce disposal costs for the grounds department and increase the total compost that LaFarm is able to create. LaFarm would therefore not have to purchase any additional compost, and would be able to sell excess compost back to the community to increase its revenue used to operate, or give compost to Easton community gardens. Despite the large initial costs of establishing a composting program of this type on campus, it could lead to monetary savings for the college in the long run. Some of these savings include reduced tipping fees at landfills, additional savings from reducing the amount of compost purchased by LaFarm, and as much as $1,200 per year from the reduced demand for garbage bags in dining halls which has been seen at other colleges of similar size (“Compost – Dickinson College Organic Farm,” n.d.).

Alternative 3: Outsourcing

The economic context and costs associated with outsourcing are completely dependent on the choices Lafayette and the Office of Sustainability makes with the technical aspects of the system described earlier. In general, all of the costs for the outsourcing alternative would come from the costs of transferring Lafayette’s food waste to American Biosoils and any added labor, transportation, or equipment costs if necessary.

In terms of payment to American Biosoils, American Biosoils charges $55 per pickup and $50 per ton of organic waste collected (American Biosoils & Compost, n.d.). Although this price could change if Lafayette agreed to create a closed food loop system with American Biosoils, we will assume the $55 and $50 price tags for any cost estimates. Further, based on data collection from Upper Farinon and Marquis Dining Hall, we estimate that Lafayette produces between 2,000 and 2,500 pounds of food waste per week between the two dining halls. If Lafayette were to leave all of its food waste non-pulped and specify a once-per-week pickup schedule for American Biosoils, the cost of pickup and tonnage fees would amount to $3,150 to $3,525 per 30 week academic year. This cost may increase or decrease depending on some of the routes Lafayette could choose to go. For instance, the cost would decrease if Lafayette decided to pulp some of its food waste and restrict the amount of food waste that it outsources. Likewise, if Lafayette decided on a pickup schedule involving two pickups per week, the costs would significantly increase. Finally, if Lafayette chooses to create a closed food loop system with American Biosoils, Lafayette would also have to pay for the compost American Biosoils produces; but, American Biosoils could potentially reduce the pickup and tonnage costs if this were the case.

Any labor, transportation, and equipment costs associated with outsourcing would be contingent on the delivery system Lafayette would select. If Lafayette used American Biosoils for pickup, there would most likely be no added costs for labor, transportation, or equipment as the existing student compost managers could move the waste from dining halls to the pickup location. Conversely, if Lafayette decided to transport the food waste to American Biosoils on its own, the college would have to invest in more labor, transportation, and equipment for this process. For labor, the transfer process would require employees or student compost managers to load the food waste into a truck and drive the waste an hour to the American Biosoils facility in Douglassville. The costs of this labor would depend on which type of employees Lafayette would select for this process. The loading process would require a truck with a lift gate because of the weight of the food waste collection bins. If Lafayette’s facilities does not have a truck with a lift gate available for this process, Lafayette would need to invest $2,000 to $9,000 into a lift gate for a truck (Staff, W.T.). Finally, Lafayette would have to pay for the fuel costs of the trip between the campus and American Biosoils site.

Economic Conclusion

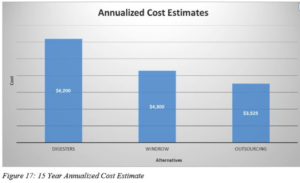

Although each of these alternatives would be a viable option for increasing food waste diversion rates on campus, it is important to look at the yearly cost for each of these options to help determine what the most economically feasible option for Lafayette is. For this analysis, we used a 15 year cost analysis which can be seen in Figure 17 below. Although these alternatives can all last longer than 15 years if properly maintained, the Climate Action Plan calls for a carbon neutral campus by 2035, which is approximately 15 years away. If these main systems are paid for by then, the college will be able to focus on increasing efficiency and size of the system implemented.

When considering the initial startup costs as well as operating and maintenance costs of each of these alternatives, outsourcing to a third party company has the lowest cost per school year. When including fee per ton of food waste as well as a weekly pickup fee of $55, it would cost the school around $3,525 per year based on current food waste estimates. Equipment costs for windrow would cost $4,333 per year, but this system would also be able to handle nearly all the waste generated on campus from both the dining halls and grounds debris. The most expensive alternative, investing in more digesters, would cost nearly $6,200 per year to pay for the startup costs and yearly maintenance. Since outsourcing is the only alternative that is cost per ton, the other alternatives would have a reduced cost if the equipment used has a longer life than 15 years. Likewise, neither of the economic analysis for the windrow or digester alternatives take into account depreciation of the equipment.

Regardless of which alternative the school chooses for the composting system, the college would be saving around $3,000 a school year in tipping fees at landfills assuming $80 per ton, as well as reducing the amount of carbon emitted during the transportation to landfills. Additionally, the college farm would not need to pay for compost if the college is able to produce its own compost through windrows or digesters. These savings could amount to almost $1,000 depending on how much compost is required at LaFarm each year.

Although the cost of the outsourcing alternative can be a relatively cheaper composting method for Lafayette, the yearly costs associated with this alternative could dramatically increase if Lafayette chooses to do multiple pickups on a weekly basis. A future partnership with the Easton composting program could also significantly reduce the costs of outsourcing Lafayette’s food waste.

In the next section we conclude our report.