Introduction

There are two important political components to consider when analyzing a societal problem. The first are the individuals or groups affected by the problem and those who could potentially be involved with the solution of the problem. The other are the policies that currently influence the problem and could possibly factor into the solution. This section of the report provides an analysis of these two political aspects by outlining the various stakeholders of the food waste issue and the Lafayette and Easton policies that influence both the problem and a potential solution.

Stakeholders

Many actors are involved in the process of increasing diversion rates, from those who are responsible for implementing a new system, to those who are affected by the outcome and by climate change in general. While every person on this planet is seeing some outcome of climate change, some populations are disproportionately affected. Minority groups and individuals with low incomes are often hit harder because either their neighborhoods and cities are exposed more to poor air quality, or their voices aren’t heard in the ongoing fight for clean air (Worland, J., 2019). Non-industrialized countries also see the impacts of climate change to a greater extent because they do not have the means to adapt to the ever changing climate. For these reasons, political action addressing problems that contribute to climate change, including the food waste issue, are important for those who do not have the influence to change how they are affected by climate change. This idea is especially prevalent when considering the other impacts associated with food waste, including world hunger and access to food. Despite the FAO reporting that one-third of the food produced in the world goes to waste and the EPA reporting that 96% of uneaten food in the U.S. ends up in landfills (Waliczek, T., McFarland, A., & Holmes, M), the world malnourished population rounds out to about 795 million people (World Hunger Statistics). Political actions could effectively address this inequality as well by reducing food waste and redistributing food resources to increase food access for the malnourished.

As for who has contributed to the problem, most people who have available access to food are largely responsible given the waste data from the FAO and the EPA. Studies have found that college students are large contributors to this food waste issue. Bon Appétit, the food caterer for Lafayette and 100 other schools and universities, recently conducted a study about college students’ food waste. A portion of the report can be seen in Figure 8 below. With a sample of twenty different Bon Appétit cafes across the country and plate scrapings from more than 12,000 individuals, the catering service found that college students waste more than twice as much food per meal as corporate employees. On average, college students were found to waste 112 pounds of waste per student per year. Moreover, the study found that people in an all-you-can-eat environments produce more food waste than in pay-as-you-order ones (Bon Appétit’s Bravo Newsletter 2019 Volume 3, 2019). All of these findings highlight an overall societal problem in college students’ dining choices. These findings also apply to the food waste problem at Lafayette since the students are mostly responsible. According to Resident District Manager for Dining Services, Christopher Brown, students at Lafayette are creating more food waste than ever before (personal communication, October 31, 2019). With the impending expansion of the school and the addition of another dining hall, the amount of student food waste will continue to grow. At buffet style dining halls, students frequently take more than what they’ll eat, or they’ll try a little bit of everything and then go back for the food they decided they liked best. If students were aware of how their plate waste affected the larger sustainable food loop, they might be more mindful of their dining habits. Otherwise, dining services cannot inform students how much food they should put on their plates. This is an important aspect to be aware of in the effort to increase diversion rates.

Since dining services at Lafayette are responsible for preparing and distributing food, they also play a role in contributing to food waste. Fortunately, the staff have already made major efforts to reduce back of house food waste to as little as possible. They use a practice called scratch cooking in which food is prepared as close to eating time as possible. When serving trays start to get empty, the next batch gets prepared. This way, there are no full batches of food that never makes it to the line. The food that is left at the end of the night unfortunately cannot be donated because there is a risk of contamination. Therefore, it is either discarded or put through the pulper. Any food that is leftover in the kitchen can sometimes be repurposed for the next day (Christopher Brown, personal communication, October 31, 2019). At grab and go style dining halls such as Gilbert’s and Lower, plate waste is less of a concern because students are given a set amount of food and the food is made to order. With predetermined portion sizes, waste at these location comes from food packaging rather than food waste since students cannot select the amount of food they receive. Buffet-style dining halls are the largest contributors, but dining services have adopted several practices to reduce their back of house waste.

The solution to increasing diversion rates has a variety of stakeholders. The Office of Sustainability is currently the most involved with composting on campus. The responsibility for the program falls under Assistant Director of Farm and Food, Lisa Miskelly. She would be responsible for implementing any changes to the system and maintaining connections with any third parties involved. Lisa also manages a group of five student compost managers who deal with maintaining the compost system. Specifically, the student compost managers are responsible for picking up food waste from Upper, loading food waste into the Earth Tubs, operating the Earth Tubs, and monitoring and recording the compost temperatures. Student compost managers who want an expanded role can also develop and manage research to improve the system and presenting information about the compost program to classes, clubs, events, or conferences (“Now Hiring Student Compost Managers!”, n.d.). The student compost managers will be impacted by any changes as their job description will most likely change as the system changes.

Closely connected to the Office of Sustainability is LaFarm. LaFarm is Lafayette’s two acre cultivate plot located three miles from campus on Sullivan Trail in Forks Township. It is part of Lafayette’s Sustainable Food Loop since it produces food for the dining halls, recycles nutrients from the on-campus composting program, and serves as an educational opportunity for students and faculty research (“LaFarm”, n.d.). Right now, LaFarm covers about half of its 6,000 pounds of produce with compost created by the school and the other half is purchased from an outside source at a discounted price from American Biosoils (“Food & Farm”, n.d.). If the compost created by the school is increased, which is the goal, then there will be more compost than LaFarm can use. Lisa Miskelly suggested that other farmers who use the land around LaFarm could be encouraged to use Lafayette’s increased compost output (personal communication, November 7, 2019). The rest of the compost created by the school is used around campus for landscaping purposes. Grounds Maintenance is responsible for distributing the compost around campus, so they would also be impacted by an increased output.

Any company that is involved in the suggested solution will be a major stakeholder. If outsourcing is the best option, then the third party responsible for taking our food waste will be involved with the school frequently. It will be important to maintain a strong relationship with the outsourcing company because the composting schedule at Lafayette is variable. This variability is due to the multiple dining locations on campus and the catering events that take place outside of the dining locations. Often times, companies that offer pick-up services have trouble dealing with multiple pick-up locations and changing pick-up times or locations. Therefore, Lafayette establishing one place for waste and maintaining a positive relationship with an outsourcing partner would contribute to a successful composting process. Further, any problems can be dealt with more easily if Lafayette has a close connection with the company. The same applies for any companies that Lafayette would purchase a digester from. As they are machines, digesters are likely to experience malfunctions and require operations and maintenance work. Again, establishing a solid partnership with the digester company will lead to more productive outcomes if any issues come up with the systems.

In the end, the composting program is an initiative for the students. Although the program does have its environmental benefits for the school, it also provides valuable educational and research opportunities for Lafayette students. This second trait is a key reason behind the composting program’s existence. According to Professor Kney of Civil Engineering, the composting program at Lafayette does not generate money (personal communication, October 25, 2019). The reason the program got started in the first place was because of student interest and faculty support. The program has also inspired other student programs related to food waste including Lafayette Environmental Awareness and Protection (LEAP), and the Food Recovery Network. LEAP is Lafayette’s student environmental advocacy group that uses rallies and campus projects to promote discussion and awareness of environmental issues (LEAP). The Food Recovery Network is a national non-profit organization that helps students at colleges and universities recover perishable food that would be wasted at dining halls and donates it to those in need (“Food Recovery Network”, n.d.). With these programs in place, students have already begun to address the food waste issue at Lafayette and would likely be part of any future solutions. As long as students continue to push for composting on campus and gain educational experience from the program, then Lafayette has a reason to maintain campus composting. Student run clubs such as LEAP and the Food Recovery Network reflect the values held by students around issues of sustainability and food waste. As much as students are part of the problem, they are also part of the solution.

Lafayette Commitments & Policies

Lafayette has a number of commitments and policies related to sustainability and energy conservation. For instance, the Lafayette Energy Policy serves as a comprehensive document that identifies energy and water conservation and efficiency as a campus issue and develops better ways to operate to reduce Lafayette’s environmental impact (“Energy Policy”, n.d.). The policy addresses a multitude of areas including buildings, new renovations and construction, lighting, heating, cooling, water usage, transportation, and others. Depending on Lafayette’s control within each area, the policies for each section can be either general policies, like Lafayette’s LCAT should be promoted, or specific, such as room temperature should be maintained at between 76 and 78 degrees Fahrenheit during air-conditioning season (“Energy Policy”, n.d.).

To date, Lafayette has three main commitments and policies that affect the on-campus composting program. The first is the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment which former president Weiss signed in 2008. Institutions involved with this group agree to conduct an emissions inventory and energy audit, declare a target date for carbon neutrality with set milestones, integrate sustainability into the school’s curriculum, and publish a climate action plan (“The Presidents’ Climate Leadership Commitments”, n.d.). Thus, this commitment led to the other major Lafayette environmental policies. One of these is the Climate Action Plan that includes the three target diversion rates for 2020, 2025, and 2035. In regards to composting practices, the Climate Action Plan provides broad suggestions but no specific strategy for achieving the diversion milestones, especially for addressing excess food waste. The other Lafayette environmental policy is the campus energy policy which includes a recycling section with fairly general policies. Specifically, the recycling section states that the Office of Sustainability and Facilities Operations are responsible for the campus recycling program and should expand the program when it is economically feasible (“Energy Policy”, n.d.). The Office of Sustainability has used this policy to create a number of recycling initiatives. Most of these initiatives, like the Recycling Strategy, have aimed to teach students what can and cannot be recycled and where certain items can be recycled. A part of this Recycling Strategy can be seen in Figure 9 below. In terms of composting initiatives, there have not been any efforts outside of the creation of the on-campus composting program described earlier in the report. If the college were to expand the composting program resources, a composting policy or educational composting initiative could help the college build student awareness and achieve its diversion rate milestones.

Lafayette College could institute stricter policies related to recycling, waste management, and food waste that could have a significant effect on the amount of waste going to landfills. There are several examples of waste management policies is cities that do just this. New York, Seattle, and some cities in California have enacted laws that make it mandatory to sort organic waste from garbage for both organizations and homeowners (Waliczek, T., McFarland, A., & Holmes, M, n.d.). Although Lafayette already sorts its waste efficiently, having a concrete rule published by the school could provide solid backing for green waste management at the school. Having a rule in place now could also establish a precedent that affects future waste practices. In particular, a waste rule now from Lafayette could influence the waste practices of students from the upcoming expansion or in the new dining location for the McCartney expansion. There are also policies in Massachusetts that have banned businesses and institutions from improperly disposing of one or more tons of commercial organic waste a week (Waliczek, T., McFarland, A., & Holmes, M, n.d.). A Lafayette policy like this that sets a limit on the amount of waste that can go to landfills per week could serve as a powerful regulation that supports a strong composting program.

Easton Codes

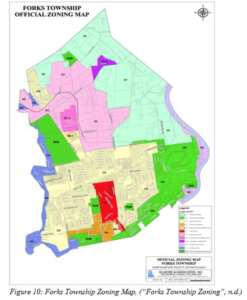

Any initiatives from Lafayette dealing with energy conservation or climate change are also subject to any relevant Easton codes. This could apply to a number of potential alternatives that Lafayette could choose for its composting program. For instance, if the college decides to increase their composting program by moving the composting to the college farm, there are certain zoning ordinances that must be considered. Both Earth Tub style composters and windrow composting would require certain permits or petitioning to be placed at LaFarm. The college currently owns about 80 acres of commercial farmland surrounding LaFarm and the Metzgar Fields Sports Complex. This land is zoned as Recreational / Educational / Municipal (REM) as can be seen in Figure 10 below. Although there is plenty of land to implement a larger composting program at LaFarm, this land does not specifically allow composting on a commercial scale (“Forks Township Zoning”, n.d.). Forks Township, the area where this land is located, allows commercial farming, but does not mention commercial composting for areas zoned as REM. There are other areas that specifically allow composting with certain setbacks and requirements such as minimum lot area of 25 acres. Because the school would be able to use this composting as an educational program for students and the Easton community, the school might be able to get the composting approved considering the large amount of acres that the school owns (“Forks Township Zoning”, n.d.). The same situation could potentially apply to the addition of composting sites on-campus if Lafayette were to be a part of Easton’s expansion to its own composting program.

In the next section we analyze the technical context of increasing food waste diversion rates.