The stakeholders of a proposed footbridge are the Lafayette community, the Easton community and the Board for the Karl Stirner Arts Trail. By analyzing these three players, our group endeavors to present a cohesive picture of the political context of a footbridge on the KSAT. Though these three key components are analyzed separately, each entity impacts the rest. In other words, these stakeholders do not exist in a vacuum, so a true analysis necessitates their overlap and intersection. Furthermore, each entity will benefit differently from a prospective footbridge. In turn, each group will also shoulder a cost of the footbridge, whether a literal economic cost or an opportunity cost.

This context analysis outlines a comprehensive political understanding of this footbridge. In other words, what policies and politics are involved with such a project. Furthermore, this political context will place the footbridge within a holistic redesign for the area surrounding the footbridge, or the Bushkill Campus. According to Jim Toia, director of the KSAT Board, the footbridge project is merely a piece of a larger development of the area. This development would also include the construction of a visitor’s center and parking lot where, currently, a car dealership stands (Toia, 2017). Then, the footbridge would serve to connect these pieces to the KSAT. Similarly, in order to be an attractive investment for the city, Toia encouraged that the footbridge include educational, sustainable and artistic components. With this brief physical outline, the political context for the footbridge can be discussed.

In order to frame this political analysis, our group is utilizing the analysis of one prominent park, Seattle’s Olympic Structure Park. Holistically, partnerships between cities and their colleges can be fraught with challenges. This analysis of Seattle’s Olympic Structure Park outlines how a partnership between a private company and a non-profit or a partnership between two non-profits can be difficult due to different visions and priorities, especially when working with a public space. Here, although Lafayette College is technically a non-profit, the school often operates as a private enterprise. Subsequently, though Ashley argues that dual-non-profit (DNP) projects find greater success, with their collective proficiency in fundraising and planning (Ashley, 2015), the pitfalls of private-public partnerships (PPPs) may more aptly apply to this footbridge. Here, Ashley points to a difference in institutional vision that consequently “favor private rather than public interests” (Ashley, 2015), especially as funding often comes from the private counterpart. As Lafayette College would likely fund this footbridge project (Toia, 2017), these pitfalls must be considered. In particular, the vision of the college and the city must be parsed out.

Figure 7: Seattle’s Olympic Structure Park

Lafayette College

Before a discussion of their priorities, however, Lafayette College’s role in the development and proposition of a footbridge on the KSAT must be understood. Broadly speaking, colleges often play a role in the civic development of the communities that surround them (Bruning, McGrew, & Cooper, 2006). However, as demonstrated in the Social Context section, the relationship between a college and its town is often complex and fraught with conflict. To this end, Lafayette’s geographical placement exacerbates the potential for division. A daunting, steep staircase overhanging a cliff is the only physical connection between the college and the town itself. Though the physical seclusion of the campus lends itself to a student body isolated from its town, the hill cannot fully account for the apathy exhibited by the town and the college for one another. For this reason, over the past few years, Lafayette has worked to engage themselves within the community. Through volunteer efforts, LaFarm, and festivals, Lafayette students have engaged with the community. However, despite its efforts to meld the two communities together, Lafayette still appears relatively detached from its city. Subsequently, it is imperative to understand how Lafayette is situated socially and politically within Easton in order to look forward to the potential implementation of a footbridge on the KSAT.

In order to understand this positioning, our group looked to the college’s master plan, developed in 2009. This master plan was created to be a guide for the college to achieve certain goals, including the aim to enhance the connection between the Lafayette and Easton communities. This master plan prides itself on being a “collaboration between members of the Lafayette College community, including students, faculty, staff, City of Easton officials and community representatives,” but the plan is written largely from the college’s perspective and for the college’s benefit. Specifically, the authors of the plan employ distinctly egocentric language throughout the plan. For example, the master plan outlines eight master principles that theoretically shape and guide the plan’s contents. Of these principles, only two mention the community outside of Lafayette. Based on this small metric, the college does not see their role within Easton as an even split between the college and Easton; instead, the aims of the college revolve primarily around itself. Furthermore, the two purposes that do include Easton (“Enhance College-community gateways” and “Improve off-campus properties to reflect Lafayette’s commitment to improve city-campus transitions” (Master Plan, 2009)) emphasize the improvement of physical connections to college hill, rather than the enhancement of physical and psychological connections to Easton.

Additionally, this master plan is nearly nine-years-old and has not been updated, so it is difficult to gauge how Lafayette’s attitudes and aims have evolved over this time. As a whole, the inclusion and consideration of Easton in Lafayette’s vision for its future suggests a collaborative and bright future for the two entities. However, written word does not necessarily guarantee action. As a result, this nine-year gap allows our group to analyze the progress that Lafayette has made, especially regarding its principles surrounding the college’s connections to Easton. The initiatives that this plan specifies is summarized with the following statement: “Physical connections to College Hill were strengthened by tying into potential streetscape improvements, reinforcing business and campus connections, and opening up campus edges to pedestrian activity along the Cattell Street corridor” (Master Plan, 2009). Clearly, the footbridge, or anything like it, is never directly mentioned in the report. Despite the lack of a direct mention, the intent and spirit of the footbridge does coincide with the master plan’s aims to bridge the two communities.

However, this nine year gap has also involved less successful initiatives between the college and the town. First, as Lafayette intends to expand their campus, they sought to build a new dormitory. Despite their efforts, the city did not approve this project. This failed effort certainly does not improve relations between Lafayette and Easton. Next, Lafayette sought to construct an elevator by the stairway behind Ruef Hall. However ,“while the college makes on choice on what to do concerning its construction plans for dorms, its plan for an elevator to downtown Easton have been put on hold” (Kelly, 2017). Together, both the dormitory and the elevator represent failed projects attempted by the college. As a result, the footbridge has the potential to join this list of failed projects, only serving to exacerbate the tense relationship between Lafayette and Easton. Conversely, the footbridge could represent a successful project between the two entities.

However, the success of the footbridge swells beyond its physical implementation. Here, ‘success’ can be defined by the footbridge’s ability bridge the disconnect between the Lafayette and Easton communities. Unfortunately, this metric is difficult to quantify. As referenced in the Social Context, the psychological ownership of a public space often results in higher levels of participation. This psychological ownership could begin with a distinct change in language in Lafayette’s next iteration of a master plan, so that the interests of the community are more equitably represented.

Easton

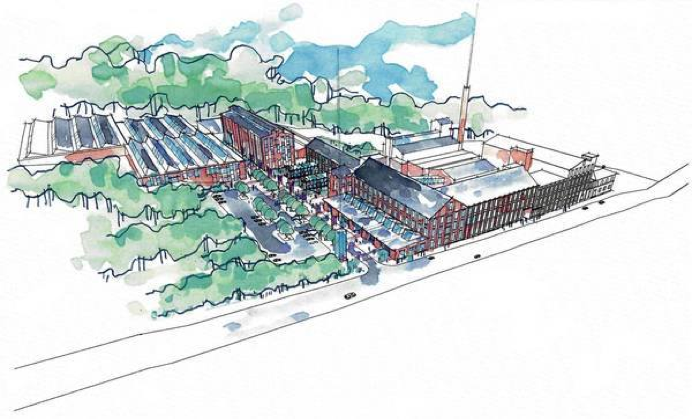

The second piece of the political context revolves around the Easton community, the missing voice in Lafayette’s master plan. Alluding to the private-public partnership previously mentioned, Easton’s position and vision must equally be considered. In light of this analysis, Easton’s Community and Economic Development Board states, “the vision of Easton’s future growth and prosperity is built upon its proud history as cultural, commercial, and transportation hub” (ECED). Following from this vision, the city of Easton has begun their Silk Mill Revitalization project. This project is “a $100 million redevelopment project with apartments, warehouse space and arts-related businesses” (Miller, 2017) that builds on the history of the silk industry that once employed much of Easton. Similarly, the proposed footbridge could connect to the history of the rope factory that the KSAT is built on (Toia, 2017). Subsequently, a footbridge could build on Easton’s mission to become a cultural and historical hub.

Figure 8: Rendering of the Silk Mill Revitalization Project

However, Easton’s political positioning reaches past the tight lines espoused by Easton’s Community and Economic Development Board. To this end, public opinion must be considered. Unfortunately, public opinion may be a difficult hurdle to overcome. Regardless of average public sentiment, those who oppose Lafayette’s expansion into College Hill are far louder than their sympathetic counterparts. As a result, based on the opinions and voices of our group and capstone cohort, the college perceives that Easton is notably against Lafayette and its expansion. This perception is solidified through opinion pieces that express how “Lafayette must execute its plans in a way that is either consistent with the vision that Easton’s residents have chosen for themselves or offers alternative value to compensate for the project’s risks. To date, Lafayette has not met this obligation” (Gaffney, 2017). Clearly, Eastonians’ potentially negative opinion of Lafayette’s initiatives should be considered in the construction of a footbridge. With a history of failed projects, such as the elevator and proposed dormitories, the footbridge has the potential to further divide these two communities and to highlight their differing views on and visions for the city. Conversely, the footbridge could act as a unifying agent between the Easton and Lafayette communities, as a peace offering between the two communities that represents their collaborative power.

With these varying opinions in mind, the footbridge has the potential to unify Lafayette and Easton’s often disparate visions. As discussed in Ashley’s research, when two organizations with differing goals work together, a project can swiftly fall apart. In order to mitigate this potential failure, the trail itself can act as a physical manifestation of the two communities’ ability to collaborate. For both Lafayette and Easton, “it has taken awhile for the community to realize the trail is there and what it offers” (Tatu, 2017). Subsequently, this trail could represent an opportunity for successful collaboration. To this end, the footbridge equally has the potential to be a shared successful project between the two entities and subsequently represent cohesion between Easton and Lafayette. With the trail as a foundation and an example of the potential for collaboration between the two communities, the footbridge can follow in its footsteps and subsequently serve to bridge Easton and Lafayette.

KSAT Board

In particular, the KSAT Board represents the pinnacle of collaboration between these two entities. The KSAT Board makes decisions regarding the artistic contributions to the trail, expansions of the trail, and maintenance of the trail (Karl Stirner Arts Trail, 2017). The KSAT Board itself involves three main groups: the Arts Advisory Council, the Board, and the Lafayette College Advisory Group. The first element is comprised of Lafayette administrators, Easton artists, Easton curators, and Easton administrators. Similarly, the Board itself includes Eastonians and Lafayette faculty alike. Furthermore, this board seems to represent a synthesis of many of Easton’s initiatives, as it pulls together Lafayette College, the Nurture Nature Center, Eastonian administrators, and outside development groups. Last, the Lafayette College Advisory Group exclusively consists of Lafayette professors and faculty, with representation from all ends of campus: economics, English, engineering, art, geology, etc (Karl Stirner Arts Trail, 2017). These groups work in unison to make decisions for the whole of the KSAT.

While these three groups work together, primarily, the Board drives the direction and vision of the trail (Karl Stirner Arts Trail, 2017). In an interesting way, this Board represents a microcosm of an ideal version of the Lafayette and Easton relationship. Through this council, members of both the Lafayette and Easton community work together to make decisions for a shared public space. As both communities are represented on this board, theoretically, the interests of both groups would be advocated for. Furthermore, combination groups such as this work to collapse the strict lines drawn around each community.

In addition, precedent exists within the Board to further collaborate and fuse the two communities. For example, in June 2017, Phillipsburg, Belvidere and Easton high school students worked with Lafayette students to add several sculptures to the trail (Sturm, 2017). Jim Toia, Chairman of the Board and professor at Lafayette College, has spoken openly about his desire to continue to fuel work between high-school and collegiate students (Sturm, 2017).

In terms of the footbridge itself, politically, the KSAT Board already has authority and credibility within the town. According to a recent news article, “the KSAT Board has complete autonomy over the trail and The City of Easton Department of Parks and Recreation completely backs the KSAT Board” (Bart-Addison, Geraghty, Kyler, & Rack, 2015). This credibility eases the political tension, as the KSAT Board should be able to maneuver the Easton politics with relative ease. Furthermore, as the board represents the interests of both communities, ideally the general public should support the initiatives brought forward by the Board.

Specifically, Toia has openly and adamantly supported the footbridge initiative. In this way, the Board, as represented through Toia’s work, is already looking into the possibility of a footbridge. Subsequently, a footbridge project has the potential to clinch the agenda-setting moment within the Board, especially as the KSAT Board has just hired a part-time curator for the Arts Trail (Tatu, 2017). Conversely, the KSAT is currently expanding and exploring the rehabilitation of a trestle by the Silk Mill into a pedestrian footbridge. This pre-existing project should be taken into consideration with the design of the footbridge. The pedestrian bridge by the Silk Mill is planned to be fundamentally utilitarian bridge (Miller, 2017), so this footbridge should endeavor to separate itself from potential redundancy by being a visual landmark, an educational opportunity, or a beacon of sustainability.

In terms of how these decisions about the footbridge should be made, consultative, deliberative and collaborative leadership has been shown to be a much more successful and productive way to govern and make changes (Lees-Marshment, 2016). Clearly, the three groups within the KSAT represent this type of leadership. Speaking more broadly, these same practices can be taken and applied to the footbridge project as a whole. In other words, all three stakeholders (Lafayette College, Easton and the KSAT) should have a voice in the project. Conveniently, the KSAT Board makes this easier. A missing voice, however, would be the student population of Lafayette College, an integral part of the disconnect between the communities but of a difficult one to incorporate in long-term organizations like the KSAT Board due to the relative brevity of a student’s residence in Easton. Through this lens, our group proposes the necessity of student voices in this project–through a collaboration of Easton artists and Lafayette art majors, or Easton civil engineers and Lafayette civil engineering majors. As a result, the student voice could be incorporated into the KSAT Board and a subsequent conversation about the footbridge.

In the end, the KSAT Board will likely be the organization to propose and execute this potential footbridge, with funding from Lafayette College. Within Easton’s political scene, the KSAT Board, as shown, has a desire to further unite the Easton and Lafayette communities. Furthermore, the KSAT Board has the credibility within the context of Easton to successfully tackle this project. Through these measures and through the collaborative nature of the KSAT Board, the pitfalls outlined by Ashley in her research should be avoided, resulting in the successful execution of a footbridge.