Introduction

In order for us to understand Social, Political, and Technical contexts cohesively, it is important to complete an economic analysis so that the footbridge project can provide value to its users moving forward. With projects containing similar scopes, it is crucial that constituencies are able to grasp the contributions that the final product can make to the community. To gain a better understanding of the underlying context, research and community engagement became the most relevant resources. Ideally, information discovered through these two methods will reveal appropriate project “phases” and ultimately shape the ways in which the economics will play a role. Specifically, for this footbridge to come to fruition, city government must be convinced that a “Lafayette Bridge” can bring legitimate benefit to the city of Easton and its surrounding communities. This means that although the bridge will not necessarily bring in direct revenue to firms within Easton, it will connect communities in a way that can leave long-term positive impacts. As a group we felt that simply pricing different materials and construction costs would be an invaluable method in developing future of this project. As we read throughout this course, creating cost estimates and avoiding community involvement would prevent us, and anyone who works on this project in the future, to overlook crucial information. Constituencies will be much more interested in the benefits of this bridge, more so from a non-monetary standpoint, and thus be more inclined to support it if the bridge can be considered to have high value. In addition, if community figures value this bridge, it is more likely to be considered holistically and the final product can be developed to its full potential.

Initial findings

In the initial stages of this project it was clear that relevant background information would set up the subsequent steps of this young project. Through research, the economic context will naturally be shaped in a way that surpasses basic financial analysis (costs, funding, etc). By taking that research and analyzing similar projects, understanding the surrounding financial aspects can be clarified. According to the Commonwealth Financing Agency, Lafayette College was granted state grants that can be used for development projects like the footbridge. A portion of this grant was devoted to building a pedestrian bridge on the Karl Stirner Arts Trail (Lewis, 2016). This information became a basis for which possible funding information and recommendations could build upon. However, before funding can be considered, the surrounding contexts must be developed and the value of the bridge must have the capacity to outweigh specific costs regarding the bridge.

Additional external sources served as valuable tools that contributed to how our economic context will be shaped. In a place like Easton, where there is a natural divide between different communities, it is important that inhabitants have accessible walkways. If our bridge can facilitate the connection between College Hill, The West Ward, and Downtown Easton the possibility for economic growth can be substantial, creating pedestrian traffic into these places. That being said, neighborhood walkability is created internally meaning that community members are the ones that ultimately decide how enhance this connection (Leyden, 2003, p. 1546). Moving forward this is important for us to consider because this bridge not only needs to be approved by city government, but it needs to be accepted by the surrounding environment and its inhabitants for any sort of benefit to be produced. Users must be able to envision this bridge in a way that will create engagement between different communities, so that the overall perception of Easton becomes more positive.

For projects that involve two main entities, such as city government Lafayette College, engaging with important constituents helps ensure that subsequent steps are completed efficiently. Understanding how Jim Toia and Dave Hopkins conceptualize this project revealed the specific type of funding the footbridge might entail. Jim Toia’s economic vision provides potential alternatives, while Dave Hopkins’ ideas cater more towards feasibility and how this project might compare to others that he has been a part of. Most importantly, however, gathering information from community contacts helps expose the potential pushback this project might encounter from additional constituents. In Economic Development for Cities, John M. Leavy explains that the main strategy to combat conflict is by engaging opposition early in the process and to acquaint yourself with them in a way that expresses the purpose of the project. Again, this project is very young so the initial emphasis should intrigue community members and Lafayette students. The foundation of our analysis, from an economic standpoint, mirrors Leavy’s idea that economic growth promotes change– physically, socially, and politically (Leavy, 1990, p. 14). While economic context typically includes financial breakdowns, this analysis highlights the potential for growth within Easton and the opportunity to enhance community connectivity. The bridge can attract students to its new cafe and brewery and also facilitate traffic from The Westward into the College Hill community. All entities involved in this project must understand the value this bridge in order for them to support it and believe in its long term success.

In order to show constituencies, and any opposition, why and how this project should be completed, it is important to present an economic plan so that they can develop their own personal value. In The Economics of Planning, Eric John Heikkila lays out a generic layout of phases: define the project, determine who and what has standing, catalog changes to surroundings, and asses the value associated with those changes. While this project will likely expand on this outline, it is notable because decision makers will want to see long term effects that will follow the implementation of a footbridge. A concrete plan of execution is a method that can be used in persuading decision makers that the footbridge is needed and can add value. Jim Toia emphasized that there is large potential regarding the ways in which the new bridge can incorporate art. He repeatedly suggested that the bridge engage users in a way that differs from normal utilitarian use (Toia, personal contact). Long term, this project will not only serve as a connective tool, but it will allow for students to have unique educational experiences. In later steps of this project, contexts will shape around the ways in which the bridge can enhance Lafayette education artistically, within engineering disciplines, and even through geological studies. If contributors are opposed to this bridge initially, then a long term vision, like Professor Toia’s, will ideally create support, which ultimately can expedite the funding and construction phases.

Cost Benefit

When trying to think of the “Lafayette Bridge” in the context of a cost/benefit analysis, it becomes difficult because there are very few, indirect monetary benefits that can come from the implementation of a pedestrian footbridge. This means that this project’s must be considered in the sense of how well it will accomplish the goals of the KSAT, the City of Easton, and Lafayette College. The goal of the KSAT is to attract increased traffic to the trail. This will be accomplished by granting easier access to the trail for Lafayette students, which will entice them to perhaps use the trail more often. This could potentially build a greater appreciation for the KSAT among the Lafayette Student body, which could potentially lead to alumni generously contributing to the trail later on. This is not something that can be guaranteed or predicted in a quantitative manner, but it is a possible means of the KSAT deriving an indirect monetary benefit from the implementation of the “Lafayette Bridge”.

The “Lafayette Bridge” can also serve to make the community of Easton more walkable. Having a walkable city is very important because walkability adds social capital (“the social networks and interactions that inspire trust and reciprocity among citizens”) which enables a city to grow economically (Leyden, 2003, p.1546). Leyden has also discussed “empirical linkages have been found among social capital, the proper functioning of democracy, the prevention of crime, and enhanced economic development” (Leyden, 2003, p. 1546). Though the monetary value of this is not quantitatively countable, the inherent value of these benefits is very apparent and could serve to make the “Lafayette Bridge” a powerful tool in the development of this social capital.

While the costs are more easily quantifiable and can seem quite foreboding when considering a project that will not earn any direct revenue. However, that is no reason to believe that the “Lafayette Bridge” will not be able to offer any value to the City of Easton or Lafayette College. On the contrary, there are several social benefits (refer to “Social Context”) as well as potential for economic growth that possibly offset the monetary costs.

Funding

For projects that involve both City Government and College institutions, specific funding is usually needed. This step, however, is usually completed after the surrounding context is fully developed. As mentioned earlier, state public funding had already been provided to Easton for similar development work, and a portion of that funding had been set aside for the Karl Stirner Arts Trail. Moving farther into the research process revealed that all alternatives must be considered with a project as young as the footbridge. Specifically, private funding emerged as an option. Initial conversations with Professor Toia reiterated the potential for pushback, especially pertaining to funding. This confirmed that paying for the bridge is a process that will be dictated largely by how the preceding context develops. On the contrary, he made a point that the “need” for the bridge will outweigh any cost burdens, leaving the potential for private donors to consider providing the funds needed.

Dave Hopkins, on the other hand, accentuated the bridge’s ability to connect the community and engage its users. He shared with us relevant numbers and figures, and shared with us what he thinks the bridge will cost financially. While he spoke of another bridge, closer to the silk mill bridge, he believed that the utilitarian purpose resembled our vision of the Lafayette Bridge. The grand total of the silk mill bridge would total $250,000– half of which was accrued from the bridges foundation alone. Other costs came from activities such as mobilization, site restoration, and the repaving of the surrounding pedestrian paths (refer to figure 1). Unfortunately, similar funding to the silk mill bridge is a rather unlikely possibility for the Lafayette Bridge, in terms of state funding. These costs, however, provide a reference for which the range of costs for the new footbridge might be.

Jim Toia’s reaction to this new information confirmed Eric John Heikkila’s idea that changes must be cataloged and the value of the assets will adapt. By expressing the concerns regarding the information Dave Hopkins’ provided us, it was interesting to see how Jim Toia confronted that conflict. As this project is developed in the future, one step will be finding Lafayette alumni that are willing to donate upwards of $500,000 to fund a bridge that can tie a utilitarian bridge to art, athletics, and education (Toia, personal contact). The various components of this economic analysis need to be utilized strategically to ensure that donors understand the bridge’s value. In addition, we highlighted various materials in our technical section help people visualize a final product. This message needs to be conveyed at a large scale so that potential donors will value the potential of enhanced community engagement and ultimately provide the necessary funding for this to come to fruition.

Materials/Arts

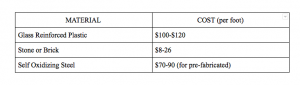

Understanding the actual costs of this bridge is an important next step. While there is no design for this bridge, three potential materials have been proposed. These alternatives possess qualities that can make the bridge attractive to users and donors and potentially mitigate costs. Unfortunately, the base costs of these materials range, which makes decisions tough as it pertains to incorporating an artistic component. As mentioned in the technical sections, we analyzed three materials: glass reinforced plastic, stone/brick, and self-oxidizing steel. Glass reinforced plastic would be economically efficient in terms of installation and maintenance but would likely limit artistic value. Stone or brick would provide artists with a unique “canvas” that will be long lasting and become stronger with additional load . Unfortunately, however, installing stone or brick usually takes a long time, which might be undesirable to donors that want to see this project erected quickly. The last alternative is self-oxidizing steel, which is the material Dave Hopkins chose for the silk mill bridge. This material is easily shipped and installed and also is a very cost effective choice. The cost per foot for each of the three materials can be referred to in the Figure below.

In addition to materials, there will be additional costs accrued that must be considered before funding can be solidified. Most of these costs will likely come from labor, construction, consulting services and maintenance. For a pedestrian bridge project with this scope, the process of precasting the structure, shipping, and installation can be done in a rather quick time period. The reason that Dave Hopkins chose weathering steel for the silk mill bridge was due to the convenience of the construction. With that project, consulting services and geotechnical analysis contributed to a large portion of the costs. Implementing the bridge’s foundation is the most cost burdening component, because once this is developed it is then a matter of getting the structure on sight. That being said, incorporating an artistically aesthetic structure has the potential to elongate this process. In the future, creating design proposals and collaborating with Easton’s local artists will dictate how effectively we can mitigate this auxiliary costs.

For a description of potential designs for this footbridge as well as a comparison of materials, and other technical considerations, follow the link to our Technical Analysis.