The creation of a bridge, any bridge, involves far more than just connecting two points. Likewise, the addition of a bridge to the KSAT concerns a variety of “social”, or non-technical, contexts. These contexts can be framed as arguments in support of developing this bridge. We will focus on 3 major contexts: a Recreation and Public Health Context, a Historical and Cultural Context, and a Community Context. In addition, we will focus some attention to environmental considerations as an important area to consider when considering the feasibility and benefits/disbenefits of this project.

Recreation and Public Health

Increasing the Connectivity and Usability of the Karl Stirner Arts Trail

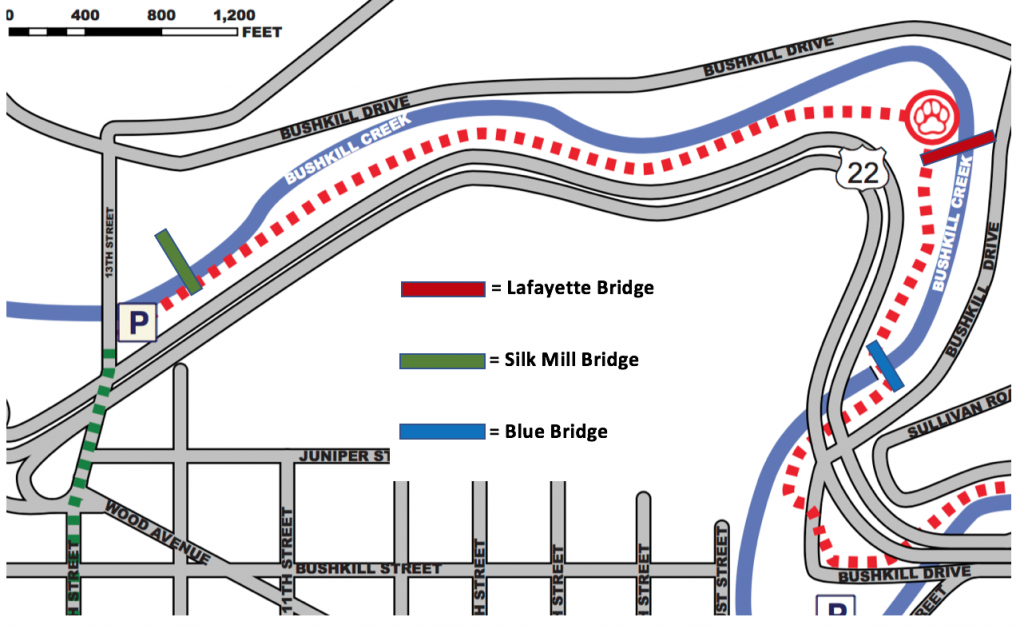

Map of the Karl Stirner Arts Trail, with current and potential future access points shown

The first and most obvious argument for proposing another footbridge on the Karl Stirner Arts Trail (KSAT) is to increase the connectivity and usability of the trail, a currently underutilized and underappreciated space. When we refer to the trail, we specifically mean the 1 mile section of the trail that lies on the western bank of Bushkill Creek (technically, the KSAT follows the river for 1.75 miles- see dotted red line on Figure 1). Currently, the trail has two entrances, at the blue bridge and 13th street . An additional proposed bridge would be placed approximately halfway between these two points (see Figure 1). We would argue that this bridge would create a more cohesive experience and more opportunities for usage of the trail. Additionally, it would have the opportunity to enhance and be enhanced by additional developments in the works for the KSAT.

The trail as it exists may appear inaccessible to users because of its lack of access points. Those who want to access the KSAT by car can park at the 13th street entrance parking lot, or at a small parking area about halfway between the blue bridge and our proposed bridge (we’ll call this the “Lafayette Bridge”, for clarity’s sake) (see Figure 1), then walk back and enter through the blue bridge. Both of these areas could also be accessed by foot, but the 13th street area is not currently pedestrian-friendly, and the blue bridge is only accessed by snaking through up to a third of a mile of other paths to get to it.

Our proposed bridge would provide an access point that would bring pedestrians directly from Bushkill Drive to the trail, arriving adjacent to the trail’s Dog Park. Another project occurring at the trail is a bridge about a quarter of a mile from the 13th street entrance, designed to connect the KSAT with the newly rehabilitated and developed Simon Silk Mill area (D. Hopkins, personal communication, November 2, 2017) (We’ll call this the “Silk Mill Bridge”- This bridge has funding and plans, and is expected to be complete during the Fall of 2018). The Technology Clinic, a course at Lafayette College in which teams of students from each academic division work together on imaginative solutions to real-world problems for clients (https://techclinic.lafayette.edu) is working to rehabilitate a train trestle that currently crosses the creek for pedestrian use, creating yet another access point, but we will discuss benefits of our proposed bridge as if this portion was not occurring (The addition of the train trestle rehabilitation would only strengthen our points, and since there is no anticipated start or end date for this project, we cannot consider it as an addition to our argument). The implementation of all of these access points will turn an out-and-back trail into a connected system of paths, with our proposed footbridge being key in providing variety and increasing the usability of this area.

The benefits of more connected and usable trails are numerous, especially with regards to the wellbeing of the community. A mixed methods research project conducted in Western Australia, published in EcoHealth, identified “significant relationships found between perceptions of green space and self-reported health” (Carter & Horwitz, 2014). Community members in this study who had access to green spaces that were perceived as being connected and usable quantifiably reported better mental and physical well-being and used the trails more often than community members who perceived the spaces near then as inaccessible. This shows that merely providing green space for a community is not enough; the space is only as good as the way to get there. Clearly, the perceptions of the residents of how usable, safe, and accessible a space seemed was valuable enough to significantly increase their feelings of mental and physical well-being. In another study, Michael Southworth discussed the value of city planning and design as it could help foster a greater sense of walkability. Designing the Walkable City looked at how a more walkable city could increase mental and physical health in the community. One issue that the study mentioned was the issue of obesity and how designing a more walkable community could potentially mitigate high obesity rates. As “walking is the most accessible and affordable way to get exercise” (Southworth, 2005, pg 248), community members would have equal opportunity and availability to exercise. Along these lines was another study done in Los Angeles to address the value of recreation in regards to physical health, which found that areas with more usable parks and nearby green space had kids with lower BMI’s (McDonald, p.180). Similarly, green space use has been connected to improved mental health. Rob McDonald dedicated an entire chapter of his book Conservation for Cities: How to Plan and Build Natural Infrastructure to Parks and Mental Health, where exposure to nature was credited with providing opportunities for socialization and recreation as well as decreased levels of anxiety, thereby improving the mental health states of users.

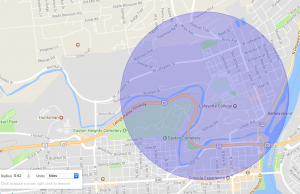

Figure 2: 0.62 Mile Radius from new bridge location

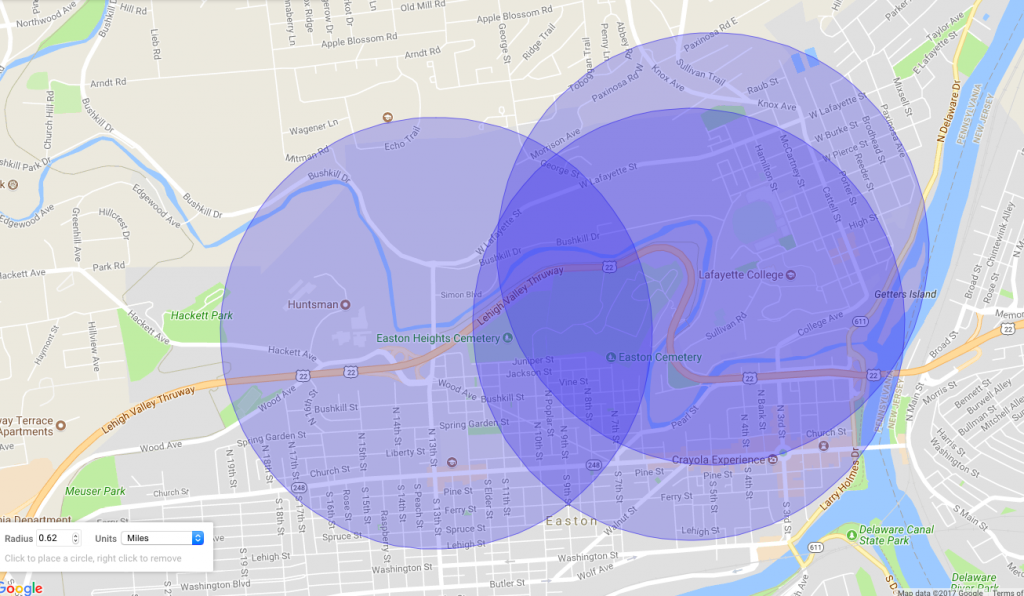

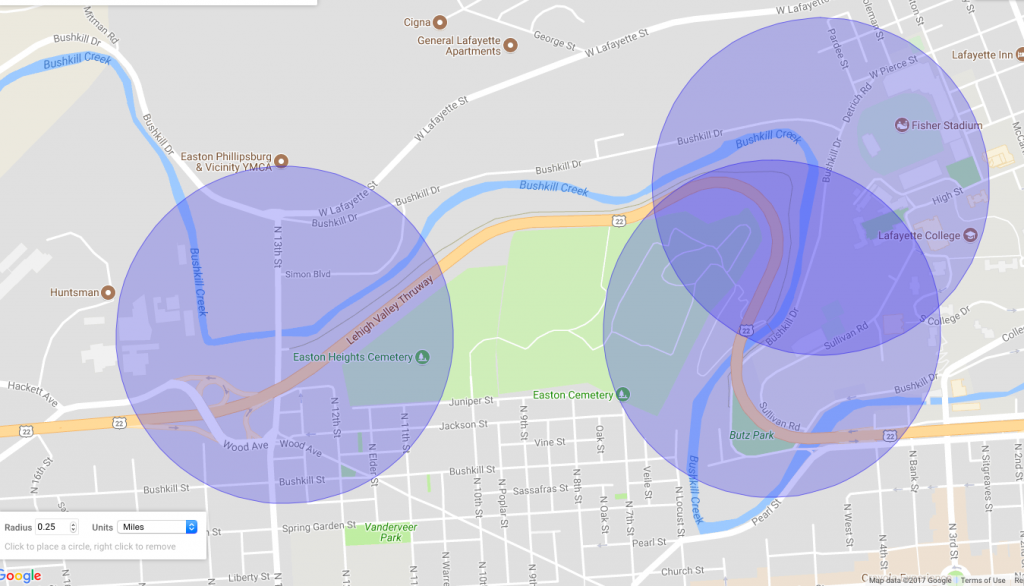

While these physical and mental health benefits can be realized with the use of the Karl Stirner Arts Trail, increasing the usability and connectivity of this space is key to provide the full potential of such benefits. Connected and usable spaces are defined as being in good condition, having visible access points, a clear pathway, and are perceived by users as safe and pedestrian friendly (Carter & Horwitz, 2014). Further, McDonald found that the majority of park users came from within 0.62 miles, about a 10 minute walk, and living 0.25 miles or less from the parks increased the likelihood of attendance even more. Our proposed footbridge would further both of these ends. Providing another access point would increase connectivity of the KSAT, providing more options for where to walk and more possible opportunities for recreation, provide another visible access point, portray the KSAT as more well-kept, and allow the KSAT to have a further reach of potential users. [Figures 2 and 3 show a 0.62 mile radius from the proposed footbridge and a 0.62 mile radius from the two current entrances and the proposed entrance, respectively. Figure 4 shows a 0.25 mile radius from these same 3 entrances.] In creating a more connected and cohesive environment at the KSAT, users of the trail from many Easton neighborhoods, who currently lie within this 0.25 or 0.62 access range, would benefit. Additionally, having a footbridge near an entrance to both the Lafayette Campus and College Hill neighborhoods makes them more a part of the KSAT narrative, with the bridge serving as an artistic gateway to this section of Easton.

Figure 3: 0.62 Mile radius from 3 access points: 13th street, blue bridge, and proposed new bridge. Users within 0.62 miles of a park are more likely to use it, according to Conservation for Cities: How to Plan and Build Natural Infrastructure by Rob McDonald.

Figure 4: 0.25 Mile radius from all access points. Living within 0.25 miles of a park increases likelihood of attendance (McDonald)

Historical and Cultural Context

Contributing to Easton’s Art Culture

The history and culture of Easton also inform the desire for a new footbridge. Easton has a very rich and present art culture, partially to the credit of Karl Stirner himself. Karl Stirner was considered a pioneer of the arts in Easton. Following his service in WWII, Stirner moved to Easton and converted an old factory, located in Downtown Easton on Ferry Street, into the Easton Art Studio. Here, he worked and taught, inspiring artists in the area. In the 1980’s, he held art showcases at the studio and encouraged artists to move to Easton. This flourishing of art and creation in the downtown area was a significant spark to the downtown revitalization that followed, and this art culture, largely started by Stirner, has prevailed. (Karl Stirner, 2015)

Today, you can see artists set up to paint by the intersection of the Delaware and Lehigh Rivers on a sunny day, or buy the work of local artists at Easton’s Annual Riverside Festival of the Arts. The existence of the KSAT itself is an exemplification of this culture, and deserves to be further celebrated and recognized, as it was this culture that helped make Easton what it is today. By acting as an additional art piece to the Karl Stirner Arts trail, our footbridge would further showcase Easton’s art environment. Further, the implementation and celebration of art in urban spaces has the ability to contribute to an area’s social and economic revitalization, and Easton is no exception.

The importance of art in public spaces is undervalued. The existence of this bridge as an art piece in conjunction with the other KSAT sculptures would create an even stronger public art space and enhance the Easton art culture. In Art Spaces, Public Space, and the Link to Community Development, Carl Grodach argues that community art spaces can “enhance social interaction and engagement” (Grodach, 2010) and generate economic activity, as Karl Stirner’s studio did in the 1980’s. Further, Grodach explains that “the ability of art spaces to realize these outcomes is linked to their role as public spaces”, and “their community development potential can be expanded with greater attention to this role”. In other words, recognizing an art space as a public space, defined as a “common ground where people carry out the functional and ritual activities that bind a community (Carr, Francis and Rivlin, 1992, p. xi)” (Grodach, 2010), can enhance its ability to enhance the community it is in and generate beneficial activity. The Karl Stirner Arts Trail by nature is the intersection of art space and public space, and our footbridge would be designed to enhance this art space, potentially involving local artists, and furthering these means.

By implementing art in public spaces, surrounding areas have the potential to realize significant benefits. Within the past few decades, the introduction of “the arts” in cities has been recognized as a successful strategy in “revitalizing America’s urban centers” (Rosenberg, 2005, p.6). An excellent example of this phenomenon in practice is the construction of Lincoln Center in New York City’s Upper West Side. Lincoln Square was chosen as a site of urban renewal in 1955, where the construction of the Lincoln Center of the Performing Arts would occur. In barely a decade, this Lincoln Square transformed from a piece of a rough neighborhood, the same neighborhood depicted in Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story” (Rosenberg, 2005, p.7), to a cultural hub. In the years following, crime rates reduced, activity and investment in the area increased dramatically, and as a result, “Taxable property in the Lincoln Square area appreciated 1,724 percent between 1963 and 1999-a growth rate three times that of Manhattan” (Rosenberg, 2005, p.7). This is just one example of the many times art has driven social and economic change. The nature of revitalization spurred by art is strong; such that its effects are capable of completely transforming an area, and numerous following generations can benefit from the effects of that transformation. As Easton desires to and makes strides towards becoming an increasingly friendly, walkable, and desirable city, the usage of art can only assist in this endeavor.

Community Context

Enhancing Community Relations: Looking at the Lafayette College- Easton Town-Gown Relationship

Our third relevant context to be considered focuses on the community surrounding the trail, specifically Lafayette College and Easton, which are problematically viewed as separate communities. The current relations between Lafayette and Easton are not operating at their full potential, especially now as the College attempts to march forward with its expansion plans and is met with resistance from College Hill residents. (see Figure 5). We will argue that the proposed footbridge at KSAT could be a tool to help enhance this relationship.

Figure 5: College Hill Neighborhood Resident displays signs protesting Lafayette’s expansion. Photo courtesy of team member.

The relationship between a university and the area which it is in is often referred to as a town-gown relationship. This relationship has been likened to an arranged marriage that can not be ended, no matter how the respective partners feel about each other. As with any kind of relationship, there are some very successful relationships between towns and universities, and others that are not so much. As Gavazzi and Fox argue, the most desirable and fruitful type of town-gown relationship is a harmonious one- or one that involved high levels of effort and comfort on both the town and school’s part (Gavazzi & Fox, 2015, p.190). It lends itself to the greatest potential benefits, as opposed to relationships where effort or comfort levels are low. The Lafayette- Easton relationship could currently not be described as harmonious- however if this could be reached, both Easton and the College could benefit greatly.

The Lafayette-Easton town-gown relationship has a lot of room for growth. Aside from the unwanted expansion, Lafayette may be perceived poorly by members of the community for a variety of reasons. This is not uncommon among many universities and their “gowns”; historically, town-gown relationships have been tense. Part of this stemmed from the adoption of the campus model, when colleges and universities transitioned to being self-sufficient spaces where students could eat, sleep, be educated, and be entertained without leaving the confines of their campus. This created an invisible barrier (Bruning, McGrew, & Cooper, 2006) around campuses, making them appear closed off to community members. This same phenomena occurs on College Hill. There is a feeling among community members that the neighborhood is divided into Lafayette and then everything else, so when Lafayette threatens to expand, it is natural that the community would feel threatened. Additionally, many university towns, especially those that have tight budgets, “have grown wary of providing services to institutions that are immune to local zoning regulations and absolved from paying taxes (Steinkamp, 1998, p. 24)” (Bruning, et al., 2006), deepening the town-gown divide.

At its location on the fringes of both Lafayette’s campus and downtown Easton, the KSAT exists in this in-between space, which has potential to foster interaction between residents of College Hill, Lafayette College, and Downtown Easton. Arguably, Easton’s communities may have a poor perception of the College because they are not familiar enough with it, don’t spend any time on campus, and have little interaction with the students. The footbridge we are proposing has the potential to be a common space for Easton and the Lafayette community. With a bridge that backs up to campus, students, as well as residents of the College Hill neighborhood, would have a closer, more direct, and safer access to the trail. Considering that the Simon Silk Mill, near the end of KSAT off of Bushkill Dr, is in the process of being redeveloped, there is a potential for the proposed bridge to serve as an easier way to access the Silk Mill, as well as the Silk Mill’s existence to encourage more people to use the trail.

The benefits of more interactions between the college and the community extend to both parties, however we would like to acknowledge that an important perspective that is often lost when looking at town-gown relationships is that of the community member. Instead, the focus is often on how to further engage colleges, which provides more immediate benefits to the universities and its students. To turn it around, the benefits of a more engaged community can benefit those communities members, the town-gown relationship itself, and the colleges. A study done by Bruning, et al. looked at these benefits that could be realized when community members took advantage of campus benefits, such as attending cultural, intellectual, and athletic events. The study, which surveyed community members in one town, found that engaged community members tended to view the school more positively and as more of an asset to the town than a nuisance, as they often benefited and felt enriched by their involvement with the school and attendance at events. The universities that are engaged benefit from this as well, as they are better able to deflect criticism from the community, and integrate the teaching, research, and service missions of their college. (Bruning, et al., 2006)

Often, in order to engage universities and towns, the strategy that is often employed is to provide students with access. Instead, “supporting efforts that link the town and the college/university to a common destiny by enhancing the physical assets of the institution while concurrently preserving the heritage of the community” (Bruning, et al., 2006) can better connect towns and universities. When a common interacting space and a common goal is established, the natural thing that follows is a better engaged and positive town-gown relationship. The new KSAT footbridge could further this goal, as it could connect the two, showcase the heritage of Easton, and contribute to its cultural development.

Environmental Considerations

Environmental considerations also help to frame the motivations for a footbridge. The Bushkill Creek is a known spot for trout fishing, making it a unique ecosystem that we would not wish to interrupt. In addition, the trail area itself functions as part of a delicate and specific environment, and any man-made addition has the potential to impact this. While the KSAT has room for more visitors and is currently underutilized, it is important to keep in mind that introducing too many people to this area is not a good idea either. With an increased amount of people on the trail, it could ultimately have negative effects on the surrounding area due to the increase of foot traffic. Potential issues to consider could be associated with the maintenance of the trail as well as the possibility of increased littering along the trail. With further research which extends beyond the scope of this project, an ideal range of people that could be users of this trail without interrupting the ethos of the area, and an estimate of how many more people might use the trail as a result of implementing this bridge could be found.

The benefits of having such a bridge could also help reduce automobile use in this area. As a new access point, creating greater connectivity and providing more pedestrian-friendly routes to access the trail, the bridge makes travel to the arts trail by car unnecessary for members of the surrounding neighborhoods. As discussed in Michael Southworth’s Designing the Walkable City, having a more walkable community could lead to a more sustainable community where people feel more inclined to walk rather than drive. This bridge has the potential to encourage people to use “greener’ modes of transportation such as walking, biking, etc. and stave away from the use of vehicles. “Walkability is the foundation for the sustainable city; without it, meaningful resource conservation will not be possible” (Southworth, 2005, pg 248). The bridge has the potential to reduce the amount of vehicles on the road and promote a healthier and more environmentally friendly way of transport for community members. Going further, with a decrease in vehicle usage, Easton could also reduce its overall fuel consumption. It would also limit the amount of noise pollution from vehicles on the road which would be supported by nearby community members. This bridge could help transform Easton into a more sustainable city that will improve the well-being of the community.

To read about the political narrative surrounding this project, please follow the link to our Political Context.