An economic analysis of a bridge requires an analysis and judgement of its value. However, much of the value of a footbridge is derived from the purpose it serves a community, rather than its monetary returns. Subsequently, return on investment will be judged based on the intangible results of such a footbridge. As our Social and Political Contexts have outlined, a bridge could serve to unite the Lafayette and Easton communities through its physical manifestation of their ability to collaborate. Though a dollar sign is difficult to put on this asset, one might say this benefit is priceless. Furthermore, any educational programming or environmental benefits would be equally difficult to fiscally quantify. Last, as the footbridge represents a piece of a larger redesign of the area, the footbridge can be understood as an investment towards a larger, cohesive, and future project. Despite the benefits of a footbridge being largely intangible, the direct and recurring costs of a footbridge are explicit. In this sense, as a design is chosen for such a bridge, its economic impact will become increasingly integral to the success and validity of the project.

In an effort to understand what these direct and recurring costs would be, our group looked to similar projects as a point of comparison. First, our group looked to the footbridge proposal by the Silk Mill Revitalization project. The goal of this bridge is to “connect the trail to the newly renovated Silk Mill project.” At the beginning of the project, Toia expressed, “it’s a pedestrian bridge, but it’s also an arts piece” (Lewis, 2016). However, over the course of the project, the bridge’s functionally began to preempt its aesthetic; as a result, the eventual bridge design represents an fundamentally functional and utilitarian pedestrian footbridge. This functional bridge cost $250,000 and was funded by grant from the Commonwealth Financing Agency. As a result, our group can predict that this project’s footbridge would meet and exceed the cost of a purely utilitarian bridge, as our bridge hopes to realize Toia’s aims of an artistic bridge. To this end, we estimate that $250,000 will be a minimum cost for this bridge.

Furthermore, this Silk Mill footbridge provides this future bridge with opportunities for grants. In other words, it seems feasible that a future footbridge could receive similar economic support, as this proposed bridge would be providing a similar purpose to its Silk Mill counterpart. For example, the Silk Mill received its funding in part because it connected the trail to a developing area. Theoretically, this proposed bridge would connect the trail to the Bushkill Campus, in some future version of the area. However, as of now, the footbridge would connect the trail to an auto repair shop. Subsequently, our group recommends that this footbridge is delayed in its construction, so as to become a part of a larger redesign of the area. Thus, if the auto repair shop becomes a visitor’s center, per Toia’s vision, then this proposed footbridge could cohesively connect the two areas. As of now, however, spending $250,000 to merely connect the trail to a sidewalk does not seem as economically feasible.

Funding:

Most of the costs will be in the upfront construction of the bridge and its prolonged maintenance. However, the intangible value of educational programming and aesthetic components have the potential to offset the costs of the bridge. In this way, combining a physical footbridge with a holistic vision of educational and artistic components will make a footbridge significantly more appealing to a future benefactor. To this end, in our conversation with Toia, he expressed,“it’s going to take the college, and maybe some academic programming, or an alumnus who sees the value of this, both as an educational moment and vehicle for the college as well as a reach out to the community” (2017) to receive funding. Subsequently, the intangible value of this footbridge will primarily serve to justify its construction and to counteract its costs.

In lieu of an independent donor or benefactor, the KSAT Board could equally be considered an option for funding. However, the economic context of the board would need to be considered. Toia expressed that a $3 million endowment would allow them to achieve a $160,000 working budget for every year. That working budget would then give them the freedom to make any improvements they see fit, like a footbridge. An argument against spending money on the footbridge right now would be for a better allocation of these desired funds. For example, a part-time curator is desired, and Toia estimates that would cost them $50,000 (Tatu, 2017). Thus, the funds of the footbridge, if accrued, would not necessarily be the most effective use of funds for the KSAT Board.

The third option for funding involves Lafayette College sponsoring the footbridge. This option provides the most conspicuous positive social implications. Alleviating the financial stress from the KSAT would allow them to move towards their other goals of the full time curator, $3 million endowment plans, and any other improvements they find fit to best benefit everyone. Not having the city of Easton pay for the footbridge would hopefully be repaid in political cooperation for its construction. Despite these benefits, if Lafayette were to solely finance the project, this funding could be perceived as Lafayette attempting to expand their control over a developing Easton area; this source of funding has potential to feed into the “Lafayette takeover” sentiment rejected by many residents. However, this drawback assumes the most extreme version of negative public opinion surrounding Lafayette’s potential sponsorship.

Long Term Considerations

Beyond the direct costs of the footbridge, recurring costs must also be considered. As the trail operates as a non-profit, its maintenance poses a potential challenge for the proper installation and upkeep of a footbridge. While the long-term costs of a footbridge would vary based on its design, they still must be taken into consideration.

Weatherproofing. Weathering of the bridge will occur as it outside, but the extent to the weathering will occur is directly linked to the materials chosen for the bridge. Flooding also needs to be taken into consideration when it comes to that material choice, as the Bushkill is prone to flooding. For example a fiber reinforced plastic would increase the initial cost of the project by about 10% when compared to concrete, although it would weather less (Nishizaki, Takeda, Ishizuka, & Shimomura, 2006).

Maintenance. Similar to weatherproofing, maintenance is also intertwined with the actual material of the bridge. Taking weathering into account, the FRP’s are waterproof and would require less upkeep in the long run, compared to concrete. In a life cycle cost study of both FRP and prestressed concrete bridges in Japan, results concluded that “FRP bridges [have] a competitive edge over other types of construction in spite of its initial cost and that FRP footbridges are more efficient when longer life is required in severely corrosive environments” (Nishizaki, Takeda, Ishizuka, & Shimomura, 2006). In terms of bare minimal construction, FRPs seem to satisfy the Bushkill’s need for a corrosion-free material and require less overall maintenance. However, FRPs may not fit the needs of artistic designs, so yet again a cost benefit analysis needs to be done by the decision makers to optimize their desired vision and budget.

Responsibility. A deciding part of the feasibility of the bridge will be its contingency plan, especially as the Arts Trail is run by volunteers. Volunteers pose a potential difficulty, as they hold no financial stake in the success or failure of the footbridge. Without funding for the bridge, finding consistent volunteers to provide care and maintenance for the bridge could be difficult. However, if the KSAT Board acquires a curator for the trail, the curator could provide a monthly inspection system for such a bridge.

Lighting

The economic impact of adding lights to the bridge depends upon their purpose: whether they exist to be functional, sustainable, or part of the art itself. After discussions with Toia, the cost of lights should be minimized, as the lighting would exist for the sake of lighting the trail (Toia 2017).

In light of this restriction, the simplest option would be basic electricity feed outdoor lighting. The average cost for electricity in Pennsylvania is 13.2 cents per kilowatt-hour. While this low cost does not seem like much, it would add to the recurring costs of a footbridge. This cost of energy also does not include the upfront cost of the lights themselves, as well as the required power lines. Without other incentives, the KSAT will not gain significantly from the addition of these lights.

Conversely, solar powered outdoor lighting would adhere to the KSAT’s commitment to sustainability. Furthermore, solar lighting would provide visual and conspicuous confirmation of the KSAT’s commitment to sustainability. Online, backyard solar lights greatly range in price, which gives the KSAT Board the flexibility to weigh the actual cost of solar lighting with their social benefit. However, portable lights can be stolen, forcing the KSAT board to replace them. Furthermore, there are several potential lighting options, each with their own merits and drawbacks. For example, LEDs are more expensive but environmentally friendly compared to a typical halogen light. However, the most sustainable option remains using the natural daylight hours, leaving the trail unlit the rest of the time.

The last point of consideration, which would be the most realistic way to incorporate light into the trail, would be using lighting as the art itself or in some element. Here, the light type itself and power source are the most problematic elements. Considering the pedestrian bridge is near the road, the lighting must not be too distracting. Guzzon’s analysis of a bridge using “low-wattage LEDs” was that they “are response to ambient light levels,” making them appropriate for use near cars and use for pedestrians (Guzzon, 2013). In terms of power, these low-wattage lights could use solar sources. This element would provide an incentive with its sustainability, while simultaneously removing a recurring cost by participating in the traditional electric grid.

Other Bridges

In order to estimate the cost of a footbridge, our group chose to use other bridge designs as points of comparison. To this end, looking at different per unit costs for different footbridge designs from commercial sources shows the range of expected costs, depending upon different options.

Using commercial bridge companies, estimates can be deduced using any measurements for a potential bridge design. Excel Bridge is a commercial custom bridge fabrication company that also builds prefabricated bridges. Their structures range anywhere between “$500 a linear foot to over $2,000 a linear foot” (Excel Bridge Manufacturing Co., 2017) but are dependent upon what the actual desires of the bridge are. Anderson Bridges is an expert in creating prefabricated bridges for easy assembly. On their website they state that their structures range from “$400 a linear foot to over $1,500 a linear foot, depending on the numbers options” they provide (Anderson Bridges, 2015). When comparing the per unit cost of the Silk Mill bridge, assuming all $250,000 went to the 120 ft long structure, the per unit price is roughly $2,000 a linear foot. So, although it is towards the high end of these ranges, based on Excel and Anderson, it can be assumed that the realistic per unit price is less, when it includes the other aspects require for the bridge. If the decision is made to move forward both these companies can be consulted for a more accurate estimate.

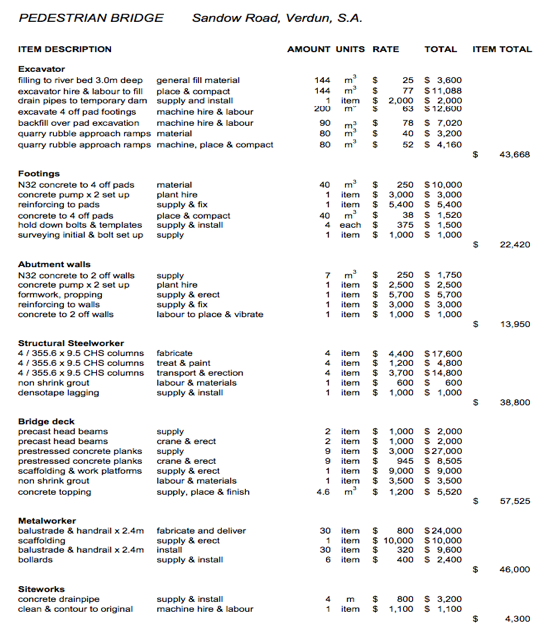

Compared to a much larger project in Australia, a pedestrian bridge was proposed for a crossing over the Onkaparinga River at a park in Verdun, Australia. The bridge cost $303,575, a price that includes everything from materials to implementation. A cost estimate report for the bridge accounted for excavating, bridge footings, abutment walls, structural steelwork, the bridge deck, metalwork, and the sitework. This bridge project is much larger than ours, with a length of 36,000 meters, and ends up including more parts than our footbridge project would entail, like having column supports. For unit cost comparisons part of their report can be found below.

Table 1: Information retrieved from http://www.walkingsa.org.au/

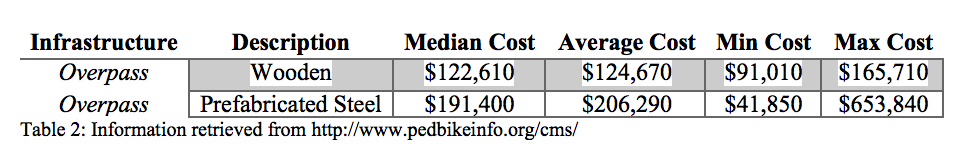

Another source is the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center, dedicated to creating “safe walking and bicycling as a viable means of transportation and physical activity” (Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center, 2017). Their organization is much more interested in the movement of people and route management. In their estimates “wooden bridges are approximately $125,000 on average, and prefabricated steel bridges approximately $200,000” (Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center, 2017). Using this resource, they have a database for costs for different options that could be used by their bicyclists and pedestrians. The PBIC created their own database for the cost options that can be used for pedestrian and bicycle safety based off of their own observed uses across the country. Below is a table of the different material bridge types; however, a link to the database is located below for any options that may be desired in the future.

Table 2: Information retrieved from http://www.pedbikeinfo.org/cms/

Economic Conclusions

Funding is crucial for this project, and the strongest argument for a footbridge involves an emphasis of its intangible benefits to the surrounding communities. Furthermore, within a holistic redesign of the area surrounding the footbridge, the bridge itself becomes merely a piece of the entire revitalization project and serves to increase its benefits to the community. Our group recommends that the funding comes from Lafayette College, but the distribution of those funds revolves around the KSAT Board, so as to maintain neutrality and minimize the perception of Lafayette’s invasion of Easton. Based on a comparison of various bridge projects, we predict that the bridge’s estimated cost will be between $250,000-$300,000, not including the art. The long term considerations of recurring costs would hopefully be addressed by a separate responsible party, like the curator. Again, the specifics of the costs depend upon the bridge design itself, but any fiscal cost will be outweighed by the bridge’s social and political benefits to both communities.