In light of the social, political, economic, and technical analyses outlined in this report, our group has compiled several recommendations for the city, the college, and especially the KSAT Board as they each move forward with this footbridge feasibility study. These recommendations ultimately connect back to the research question stated in the Introduction. Therefore, these suggestions aim to forge the disconnect between Lafayette College and Easton and facilitate the identity of the KSAT.

Essentially, our group recommends that the next steps taken in this feasibility project involve a concentrated and collaborative coordination between the three entities involved, the college, the city and the KSAT Board. Based on our collective research, a shared vision for this footbridge and for any further rehabilitation of the area will be integral to the success of both the project and the relationship between the town and college. Furthermore, this coordination should involve a discussion of the various responsibilities involved in this project. For example, our project demonstrates that Lafayette College will likely fund such a project, either through an alumnus or through the administration. However, how will Lafayette funding the footbridge shape the vision of the footbridge? Will civil engineering students help in the design? Will art students work with Easton artists to design the aesthetics components of the bridge? These are all questions that will fundamentally impact the shape and success of the project.

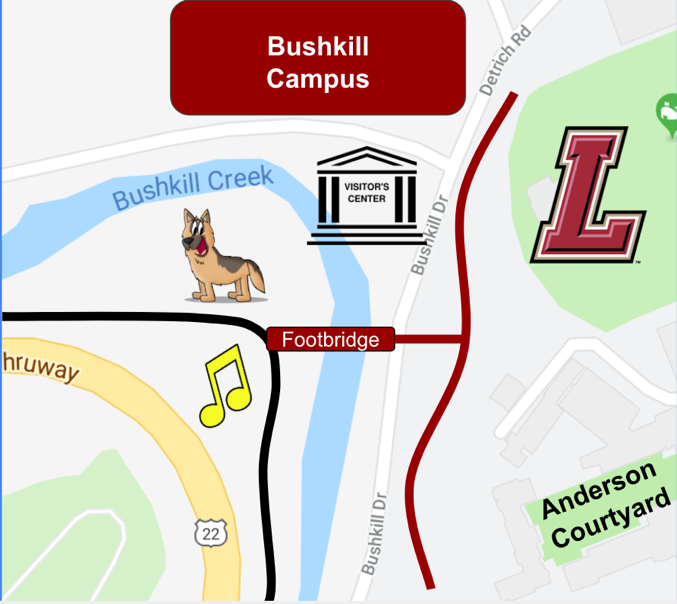

Furthermore, zooming the lens out, each of these three components need to carefully coordinate and curate a collective vision for the surrounding area. For example, the vision depicted in the introduction involves a visitor’s center in place of the existing auto-dealership. This plan depends on Lafayette buying and attaining the land of the auto-dealership, a company owned by Easton residents, employing Easton residents and serving Easton residents. To this end, the assumption that Lafayette will eventually own this land perhaps reaffirms Easton’s perception that Lafayette is expanding its reach too far into the city. Again, the careful curation of a holistic vision for the Bushkill Campus between all three stakeholders will hopefully ensure a positive and successful project that will represent the college and the town’s ability to collaborate. Subsequently, in this revision, the footbridge will represent a piece of a larger reconstruction of the area. Eventually, the footbridge could act as a conduit between the two communities and cement the KSAT’s role in the unification of the college and town.

Figure 12: Loose Outline of the Vision for the Bushkill Campus

Our group also recommends that, whenever this bridge is implemented, the pedestrian footbridge is more than just a physical footbridge. To this end, our group recommends that the bridge involves educational, sustainable, and aesthetic components. In terms of education, this bridge provides a unique opportunity to act as an educational space for both Lafayette and Easton students. Through programming between the two curriculums, Lafayette students could educate students in Easton about the history of the trail and the rope factory it sits on. Not only would these elements forge a connection between the college and the city, but it would expand the footbridge into an educational landmark.

In terms of sustainability, the bridge could provide data about the Bushkill Creek. Through this plan, sensors adhered to the bridge could measure water depth, turbidity, flow rate, pH level, etc. This information could be fed back to the college in order to inform Lafayette’s own environmental studies and sustainability education, especially as the Bushkill Creek periodically floods. Furthermore, this data could be seamlessly incorporated into educational efforts between Lafayette students and Easton students, with kits provided for third-graders to measure the pH of the water.

In terms of aesthetic appeal, we suggest that art is incorporated into the trail. First, this art will ideally fit into the ethos of the trail itself, thereby facilitating the trail’s identity. Second, the art will transform the footbridge into a visual event. With the incorporation of art, the bridge transforms into a destination in of itself, instead of merely a means to get from one side of the river to the other.

Collectively, these educational, sustainable, and aesthetic components will increase both the direct and recurring costs of such a bridge. However, the return on investment equally increases. With each of these programs, the merits of the bridge expand, as both Lafayette and Easton derive more intangible value from the project.

Circling back to the Introduction, our group posited that our goal would be to implement a footbridge that successfully synthesized sustainability, functionality, and aesthetic appeal. To this end, we again propose the following bridge as a model for a potential vision of a footbridge.

Figure 13: Mock-Up of a Bridge

This mock-up collectively incorporates all three criteria. First, it promotes sustainability as the bridge assimilates into the nature it surrounds. Furthermore, this assimilation adheres to the atmosphere and ethos of the trail itself. Second, the bridge is functional; it provides a way for walkers and runners to successfully move from one side of the bridge to the other. Third, this bridge provides aesthetic appeal. Not only is the bridge itself aesthetically appealing, but the space it provides allows for rotating art installations, a staple of the KSAT. As these three criteria coalesce, the bridge itself becomes more than just a physical footbridge; it becomes a gathering place for both communities, a visual event, and a destination in of itself. Again, these elements only increase a return on investment and a justification for funding. Subsequently, though our group is not recommending that a direct next step involve the immediate construction and implementation of a footbridge, we still have provided ample research to support our recommendations.

In summation, our group recommends that the KSAT Board’s next steps be a direct coordination between the three entities involved: the college, the city and themselves. This coordination will increase the likelihood that a footbridge will act, both in the process of its creation and in its actual existence, as a physical manifestation of the ability of the town and college to collaborate. Subsequently, the success of this project could serve to forge the disconnect between the two communities. Through this project, we have endeavored to demonstrate the intangible benefits of a footbridge and how these benefits could be best leveraged and optimized. In other words, how a pedestrian footbridge can both physically and metaphorically bridge the two communities.