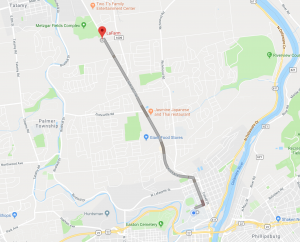

LaFarm: Located 3 miles off campus Via Sullivan Trail

Social Context

When considering the social contexts that shape the identity of a project, It is easy to see LaFarm as an entity on its own, however if we pull back, we start to see LaFarm as a part of larger systems & social movements which shape the direction of the project. First, we will contextualize LaFarm as a part of the small-scale local farming, particularly within the context of Easton & Forks Township. We will then move to understanding LaFarm as a part of the broader college farm movement, continuing with a section considering LaFarm as a part of the, Lafayette College Sustainable Food Loop, and concluding with an analysis of LaFarm and its relation to the Metzgar Athletic Complex.

Local Food & Farming

LaFarm is part of the Local Food and Farming movement. For decades, large scale, factory farms have existed in the United States and have become a the driving force behind the consumer food market. Produce that has been factory farmed lines the aisles of supermarket chains around the country, reaching millions of Americans each day. While factory farms offer convenience in the eye of the consumer, its benefits aren’t without consequence. Mainly, factory farming is degrading to the environment and while there are a multitude of practices that contribute to this, cattle production, feed production, and food transportation are 3 facets that add to the problem.

Cattle production is degrading to the environment, mainly because cows are a heavy producer of greenhouse gas emissions. In 2015 GHG emitted by cattle constituted nearly 20% of US methane emissions, equating to almost 24 billion pounds of beef production. On a global scale, a recent analysis by Goodland & Anhang finds that livestock and their byproducts actually account for at least 32.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year, or 51 percent of annual worldwide GHG emissions. (Goodland, 2009)

While cattle production constitutes a large fraction of domestic agriculture, an even larger portion can be attributed to feed production. In order to produce 1 pound of meat, it takes, on average, 16 pounds of feed. In the U.S., corn is the primary feed grain, accounting for more than 95 percent of total feed grain production and use, with more than 90 million acres of land are planted to corn per year. (Coffey, 2011) Dedicating such resources to cattle production has two main downsides. The first, is that planting corn year after year degrades the soil quality, forcing farmers to use harsh fertilizers and pesticides in order to grow the crop. Many of these chemicals are extremely harmful to the environment and only further degrade the soil quality. The second downside is that crop production for human consumption is severely limited. Dedicating such a large portion of viable land towards feed production takes away from consumer crop production, forcing consumers into purchasing non-local produce.

Because of the aforementioned issues with large-scale factory farms, there has been a shift in recent years towards supporting locally sourced, small scale farms, with a focus on farm-to-table and direct-to-consumer practices; farmers markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) facilitate these practices. The USDA reports that since 1994, there has been an uptick in the number of Farmer’s Markets domestically, rising from 1,755 to nearly 8,700 currently registered markets. Likewise, the USDA estimates that as of recent, there are as many as 3,000 CSA’s currently operating in the U.S.. (USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, 2017) Locally, LaFarm is a part of nearly 20 community farms in the Easton area. (Gardens of Easton, 2015) LaFarm fits perfectly into this narrative as it supports local farmers markets and continues to incorporate CSA into its programming through its community garden initiative. As part of this initiative, LaFarm offers 35 plots for community gardening, available for rent by the Lafayette Community. As part of its mission, the LaFarm community garden initiative aims to, “Strengthen [a] sense of community through a common goal of Stewardship & Cooperation is something that gardening can do, naturally. As members of this community we agree to steward the land, soil, food, water resources and plant biodiversity at Lafayette, in our gardens and beyond.” (LaFarm Community Garden Plots, (n.d.)) A greenhouse at LaFarm would only further these values as it would allow for increased crop production from early seed starting as well as provide an avenue for greater engagement with the Lafayette, and Easton communities.

community farms in the Easton area. (Gardens of Easton, 2015) LaFarm fits perfectly into this narrative as it supports local farmers markets and continues to incorporate CSA into its programming through its community garden initiative. As part of this initiative, LaFarm offers 35 plots for community gardening, available for rent by the Lafayette Community. As part of its mission, the LaFarm community garden initiative aims to, “Strengthen [a] sense of community through a common goal of Stewardship & Cooperation is something that gardening can do, naturally. As members of this community we agree to steward the land, soil, food, water resources and plant biodiversity at Lafayette, in our gardens and beyond.” (LaFarm Community Garden Plots, (n.d.)) A greenhouse at LaFarm would only further these values as it would allow for increased crop production from early seed starting as well as provide an avenue for greater engagement with the Lafayette, and Easton communities.

Sustainable College Farming

Student run sustainable farming initiatives are not a new trend. Colleges and universities all over the nation have had successful, sustainability driven farming programs like LaFarm for decades. However, Lafayette’s LaFarm program is at a disadvantage due to the college’s small size of roughly 2,500 students, lack of agriculture department, and the Farm’s distance from campus, three miles from college hill. In our research, we looked into a number of student-run farming initiatives and used them as case studies to make recommendations for LaFarm. One great example of a student led farm initiative is at Yale University. The structure and inception has many similarities to LaFarm. The Yale Sustainable Food Program (YSFP) began in 2000 as a result of a class analyzing the health and environmental effects of pesticides on produce. This sparked the idea to launch a project a sustainable dining program, a college farm, university composting, and increased education around food and agriculture. Driven by this ambitious vision, a steering committee of students, faculty, and staff spearheaded the direction and growth of YSFP since 2004. The program hosts a myriad of programming focused on bringing the Yale and greater New Haven communities together such as Seed to Salad (an educational partnership with local New Haven public schools), Yale student interns, Pre Orientation Harvest and more. Lafayette currently has programming in similar nature, however we can find inspiration to expand LaFarm from examples like Yale. Much like Lafayette, Yale does not have a traditional agriculture school, therefore a student run farm operates completely differently than at a larger state school. The values of sustainable community farming, education on sustainable food production, and sustainable farming classes are pervasive in both Lafayette and Yale’s programs. We can look at the success of the Yale Sustainable Food Program from their increased education at Yale related to food and agriculture and credit it to the support and collaboration from their administration.

Like Yale, Haverford College in Haverford, PA has also entered into the realm of college farms, founding their “HaverFarm” in 2010 on recommendation from their 2010 EVST Capstone Report. Much like Lafayette, Haverford College is a small liberal arts institution with a student body less than 2,500 students. It is not a coincidence, then, that Lafayette’s LaFarm was used as a case study to help contextualize the HaverFarm project as a part of a bigger picture. Since its inception in 2010, HaverFarm has steadily increased its scope of production and the scale of its operation, installing a greenhouse, on-site, 3 years later. HaverFarm’s greenhouse project aimed at  addressing the disconnect between the college and its farm, placing a focus on interdisciplinary opportunities, educational experiences, and bridging the gap between HaverFarm and the community. HaverFarm achieved this through its programming with local food banks, CSA organizations, and its Haverford Mentoring and Student Teaching (MAST) programs. Looking at HaverFarm’s success at achieving these goals through its greenhouse project sets an example for college farms around the country to effectively foster relationships between the farm, the community, and the college.

addressing the disconnect between the college and its farm, placing a focus on interdisciplinary opportunities, educational experiences, and bridging the gap between HaverFarm and the community. HaverFarm achieved this through its programming with local food banks, CSA organizations, and its Haverford Mentoring and Student Teaching (MAST) programs. Looking at HaverFarm’s success at achieving these goals through its greenhouse project sets an example for college farms around the country to effectively foster relationships between the farm, the community, and the college.

Lafayette College Sustainable Food Loop

While LaFarm operates as a separate entity by itself, it comprises part of a larger system within the Lafayette & Easton communities. “LaFarm is one component in the Sustainable Food Loop, or SFL, the central organizing principle for activity at Lafayette College aimed at pursuing sustainable food and farming practices. The SFL connects organic waste from Bon Appetit’s Dining Services with the campus’ composting facilities. The compost is then used as fertilizer at LaFarm and on campus grounds.” (Lafayette Sustainability, (n.d.)) LaFarm’s participation alongside Bon Apetit’s in the Lafayette SFL is paramount in advancing Lafayette’s sustainability initiative, advocating for education in sustainable food and farming practices. In conjunction with LaFarm, student organizations including the Lafayette Food and Farm Cooperative (LaFFCo) and LEEP (Lafayette Environmental Awareness and Protection) provide educational programming for the campus community about the SFL. This ranges from Orientation Leader training, where O.L.’s pick crops at LaFarm and work to prepare them with Bon Apetit for a group dinner, to the ‘Weigh the Waste’ program which raises awareness of food waste issues on campus. LaFarm, LafFCo, and LEEP all contribute to the SFL and the educational experience at Lafayette College, but its reaches go beyond that into the Easton community. LaFarm in particular is a member of Buy Fresh, Buy Local Greater Lehigh Valley, and has worked in conjunction with the Nurture Nature center and the Pine St. urban farm in Easton. Having worked in direct contact with community organizations, LaFarm serves as a center point for sustainable food education in the community.

LaFarm and Metzgar

Looking beyond the small farm movement and Lafayette’s Sustainable Food Loop, another key aspect to the social context of the Greenhouse Initiative is LaFarm’s connection with the Metzgar Field Sports Complex. As discussed in the introduction, LaFarm is situated on southern edge of Metzgar Field Sports Complex. Several Lafayette outdoor sports compete and practice at the Metzgar Fields Athletic Complex, including cross country, field hockey, baseball, football, soccer, lacrosse, softball and track and field. This complex has permanent seating for over 1,000 spectators. Located about three miles northwest of the College Hill campus, the field is part of an 80-acre facility which also contains fields for many of the intramural and recreational sports programs.

We believe that, for reasons previously discussed earlier in this report, the most ideal location for a greenhouse at LaFarm would be on a plot on the north side closest to Rapport Field. This location can be seen in the image below:

Source: Google Maps

As is made visible in this image, the proposed Greenhouse site closely borders the Metzgar Field Sports Complex. This physical connection fosters a unique relationship between two facets of Lafayette College that have starkly different visions and interests. While the Athletics Department seeks to provide premier sporting facilities on par with competing schools, LaFarm’s mission is to integrate curriculum and practice in sustainable food and agriculture for the campus community. These diverging goals may lead to a future stalemate with respect to the allocation of land desireable to both parties. For instance, the area where we feel would be the best location for the greenhouse is also in consideration for use by the Athletics Department as well, according to Sarah Edmonds. Moreover, LaFarm manager Edmonds remarked that Athletics may view the presence of a greenhouse as an “eyesore.” The conflicting opinions of both parties will be a significant hurdle to overcome because the proposed Greenhouse location does not have a solidified designation. It is for this reason that our recommendation must be deliberate in its attractiveness to LaFarm and Athletics alike. In order to appeal to all shareholders, a mutual compromise would provide a lasting relationship comfortable for both parties. Taking this aspect of the social context into account, the prospect of a greenhouse may be more acceptable to the Athletics Department if the structure is less conspicuous. By planting aesthetically pleasing trees and plants adjacent to the north side of the greenhouse, Metzgar attendees may not notice the greenhouse.

The physical proximity of LaFarm and Metzgar clearly lead to social boundaries that directly affect the possibility of integrating a greenhouse. The inherently different missions of each interested party will undoubtedly stimulate a conflict of interest, but our group believes that careful planning and negotiations would be the most sound strategy in approach in a lasting initiative like the greenhouse at LaFarm.

Conclusion

It is without question that there has been a shift towards sustainable food practices in the past 15 years. As part of this trend, there has been a large uptick in the number of community farms across the country and LaFarm is very much a part of this growth. Community gardens have not only brought environmental and economic benefit to their respective localities, but also fostered relations amongst community members. LaFarm has worked towards engaging community members from both Easton and Lafayette through its community garden program & partnership with Bon Apetit, however these are only steps in the right direction. We consider the LaFarm greenhouse as a means of continuing to foster this relationship between the Lafayette and Easton communities.

Next Section: Moving Forward