Economic Context

According to the 2016 Capstone, LaFarm has a number of ways in which they receive income for their annual budget of $11,000. The budget is accumulated through annual donations from alumni and various donors such as the Hendrickson family, selling crops to Bon Appetit during the growing season, and the college. However, the 2016 capstone focused more on a cost breakdown of various alternative energy power sources because its research goal was concerned with a carbon neutral system. Considering our capstone is more geared towards executing on the construction of a greenhouse and less geared towards off the grid power, the cost information from the 2016 capstone report is not as pertinent. In our economic analysis, we’ve used the estimated BTUs calculated to estimate the yearly cost of energy for a gothic greenhouse.

The 2015 capstone estimated the costs for three different greenhouse structures. These greenhouse structures include a hoop house design, a gothic design, and an A-frame design. The 2015 Capstone recommended implementing the most affordable option of the three structures. Since the release of the 2015 report, LaFarm has secured funding for a small hoop house that will be at LaFarm by March 2018. A hoop house is a similar structure to a greenhouse used for early seed starting, except is not equipped with ventilation and heating systems. Their other recommendations include pursuing a gothic or A-frame style in the near future to further maximize off-season harvests. In our analysis, we’ve used their analysis of the gothic greenhouse as a starting point. Our analysis goes more in depth into exact costs of the structure.

Throughout our project, the goal has been to generate feasible recommendations that can be used in the future to integrate a greenhouse at LaFarm. This economic analysis focuses on the material and maintenance costs necessary to build and support a greenhouse of the size and caliber we’ve recommended. We recognize that when considering the economic context of any engineering project, added benefits, both implicit and explicit must be considered. As such, we discuss the monetary benefit as well as the educational benefit for the Lafayette and Easton community in this section. Another key important factor considered was how long it would take Lafayette to earn back the total fixed cost of the greenhouse. The break-even analysis, estimates metrics for the costs, benefits, and the payback period for constructing a greenhouse for LaFarm.

Cost Estimate

Material Cost

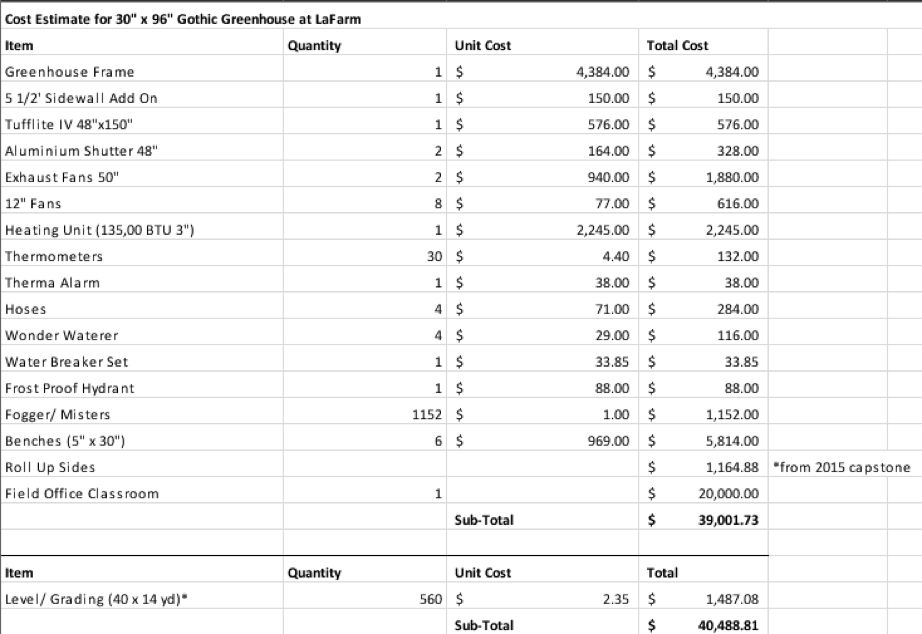

Throughout our analysis, we placed importance on building a greenhouse using locally sourced materials. All material costs were retrieved from Nolts Greenhouse Supply, a local greenhouse material distributor in Ephrata, PA. Cost estimates for the classroom, leveling and grading the surface are based on industry averages for those services plus an added 13% for the Lehigh Valley Area labor and material cost. Shown below is a detailed cost estimate for the materials needed to build and run a 30’ by 96’ gothic greenhouse.

Material Cost List

Based off of our research and conversations with Sarah Edmonds, the LaFarm Manager, we were able to estimate the amount of materials needed in our recommended greenhouse structure. In order to properly circulate the air in a 30” by 96” greenhouse, the greenhouse requires eight 12” fans (four on each side), two exhaust fans on one end, and two air vents on the opposite end. We estimated that in order to ensure proper circulation, the greenhouse requires eight 12” fans (four on each side), two exhaust fans on one end, and two air vents on the opposite end. An image of the greenhouse setup and explanation on ventilation can be seen in the Technical Analysis of the report.

The heating unit was chosen based on the number of BTUs the 2016 capstone estimated a greenhouse of this size would consume. A further breakdown of heating costs is found below in the Operational & Maintenance Cost Section.

Although greenhouses do not require automatic sprinkler systems, we recommend not implementing such a system as it adds an un-necessary level of complexity while still achieving the same goal as a manual system and did not fit the context of LaFarm. The cost estimate includes other materials needed to properly operate a greenhouse, such as hoses, a Thermalarm (an alarm set off by temperatures deviating from the set range), and benches. Although our recommended greenhouse is not as high-end as others (such as the Haverford greenhouse below), we want to ensure it functions properly so that the temperature and moisture stay within the intended range. All material costs can be adjusted slightly based on the make and quality of the materials purchased. We’ve estimated the total cost of greenhouse at LaFarm to be roughly $40,000, however, many costs are variable and could based on different material suppliers.

In our analysis, we’ve assumed our greenhouse will be a basic structure with a polyethylene exterior rather than constructing a more permanent structure with a concrete base and fiberglass windows as recommended by Sarah Edmonds. We did not add construction costs in our analysis because our greenhouse structure recommendation is very straightforward and therefore could be constructed by Lafayette’s Facilities & Operations department. The “off-the-shelf” greenhouse we chose from Nolt’s Greenhouse Supply comes with step-by-step instructions, meaning a professional construction crew would not be necessary to construct the greenhouse. However, if Lafayette decided to utilize professionals to construct the greenhouse, the labor would cost roughly $5,000-$10,000 (Capstone Report, 2015).

Operational & Maintenance Cost

All greenhouse structures run the risk of weather and damage over time. The polyethylene exterior has potential to tear in the event of severe weather conditions, however small tears can easily be patched. A greenhouse of this caliber would require marginal maintenance costs due to its simplistic functionality. The exterior polyethylene cover holds a life of about three years versus a polycarbonate or fiberglass exterior which can last over a decade. Other materials, such as the framing, benches, fans, and heating units should have a lifespan of at least a decade, given high-quality materials are purchased. The yearly maintenance cost is minimal once the greenhouse has been implemented, however, extreme weather must be taken into consideration for our proposed greenhouse with a polyethylene exterior. Inclement weather, such as harsh winds, hail, snow and rain storms could cause serious damage to the investment (Capstone Report, 2015).

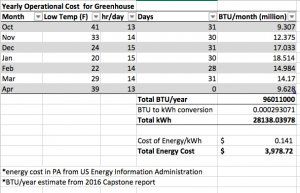

Using data from 2016 Capstone Report Appendix, we were able to estimate the yearly operational cost to heat the greenhouse. The 2016 capstone estimated a 30’ by 96’ greenhouse would require roughly 96 million BTUs per year to heat during the seed starting period between October through April. Assuming the current cost of electricity in Pennsylvania is roughly $0.1441 per kWh, we estimate the greenhouse will cost about $3,978.72 each year to operate, given constant electricity prices. A further breakdown of the analysis can be seen below.

Economic Benefit

The addition of a greenhouse at LaFarm would have environmental and economic benefits for LaFarm and Lafayette College. The main function of a gothic style greenhouse is seed starting in the winter when the ground soil is too cold for production. In order for seeds to germinate, which is when seedlings sprout, they must be kept within a specific temperature range for that specific species. Germination rates are much higher and more accurate when seeds are grown within a greenhouse rather than outside because greenhouses allow the flexibility and control to keep the soil temperature within the optimal range (ex: between 70-80 degrees F) for seed germination. Not only will it be easier for the LaFarm faculty to accurately estimate germination rates, but the volume of produce grown will increase due to the larger greenhouse area available coupled with the recent and planned expansion of LaFarm. It is hard to determine the exact increase in productivity from the addition of a greenhouse due to various factors such as the volume of seeds planted, specific species planted, germination rates, etc. However, we can infer that added greenhouse space will increase the volume of seeds started. LaFarm has increased its production space each year since its inception, nearly doubling in size. The “La Farm Phase III” intends to increase the production space further by purchasing back land adjacent to LaFarm currently rented to local farmers (EVST Capstone, personal communication, November 13, 2017). A large, functioning greenhouse would compliment this intended expansion by supplying enough seedling to support additional production at LaFarm.

In addition, there would be added economic benefit from the money saved by not continuing current operations transportation costs. In estimating the yearly cost for continuing current operations, we break down the expenses into two primary contributors; rental expense and travel expenses. According to Sarah Edmonds, LaFarm spends around $200 per month on greenhouse rental space at The Seed Farm, which includes six 10’x5’ benches (S. Edmonds, personal communication, October 18, 2017). All told this equates to roughly $2,400 per year. In terms of travel expenses, The Seed Farm is 30 miles from LaFarm, and according to Ms. Edmonds, she makes the trip an average of three times per week. Based on information provided by the Department of Energy and American Automobile Association, we assume that the average miles per gallon for a van (similar to the van she uses) is 15 and the current average price of gasoline in the state of Pennsylvania is $2.80. With these metrics established, we estimate that the total cost including rent and travel to be around $4,150 per year. This additional capital could potentially be invested in growing the production capacity of LaFarm. With this increased production capacity, LaFarm would have the potential to supply a larger share of produce to Lafayette Dining services, keeping in line with Bon Appetit’s initiative to serve locally sourced food.

Another added benefit to discontinuing operations is the time that Sarah Edmonds saves by not having to constantly travel to The Seed Farm. With this additional time, Ms. Edmonds would be able to be more productive on-site rather than spending it traveling. Beyond the intangible value of her spare time, we can also estimate the economic benefit of this additional time by factoring in a monetary value. We can monetize this benefit by estimating the value of her time and the amount of time she spends off-site. Due to a recent change in the Fair Labor Standards Act, the new minimum salary for a higher education faculty member is $47,476, according to the U.S. Department of Labor (Guidance for Higher Education Institutions on Paying Overtime under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 2016). Assuming a 40-hour work week, this equates to a minimum hourly salary of around $23. Considering Sarah travels to The Seed Farm on average three times per week and assuming she spends one hour there per visit, we can roughly estimate the value of her time at the Seed Farm to be $8,970 per year. This estimate is also undervaluing Ms. Edmonds salary so this value could potentially be higher as well.

One of the main goals of LaFarm and the Sustainable Food Loop is to combine sustainable agriculture and farming practices with LaFarm for both production and educational purposes. According to the LaFarm mission, “Our mission is to integrate curriculum and practice in sustainable food and agriculture for the campus community. We grow produce for the dining halls, recycle nutrients from composted food back to the soil, and serve as a laboratory for student-faculty collaborative research” (LaFarm, 2017). A greenhouse on the LaFarm campus would have an added benefit by enhancing educational engagement for any classes and interests groups that utilize LaFarm. The greenhouse could host a number of educational opportunities to teach students about green farming, the local food movement, sustainable, and more. Lafayette is an educational institution that focuses on the hands-on education of its students; this learning experience including opportunities such as research and field trips to LaFarm. Although this benefit is not quantifiable, the experiential and educational benefit coupled with the other economic benefits outweighs the high initial cost to construct the greenhouse.

Breakeven Analysis

A break-even analysis provides another perspective on the viability of undertaking the Greenhouse Initiative. This particular analysis aims to determine the time it would take to “break even” on the potential investment. That is, how do the direct costs of purchasing and constructing a greenhouse compare to the costs of continuing to rent space from The Seed Farm in Emmaus, PA. This examination can ultimately be leveraged as a tool to demonstrate the long-term benefits of investing in a greenhouse. In order to perform this break-even analysis, we must first consider how much it costs per year to continue operating in the current manner. Next, given the total costs calculated above, we will analyze how many years it will take to make the money back relative to the costs of continuing current operations. This break-even process is a variant of the analyses performed in prior engineering studies classes, such as Engineering Economics and Management.

In order to build out the metrics for accurately estimating the break-even duration, we consider a number of contributing factors. Some of these factors include the rent and travel costs of continuing current operations, while others include the materials and construction costs for integrating an on-site greenhouse. However, beyond the monetary costs attributable to each factor, there are addition intrinsic considerations to remain aware of. For instance, one intangible expense is the opportunity cost that Sarah Edmonds incurs from driving out to the Seed Farm each week. As we project the monetary costs of integrating a greenhouse versus maintaining current operations, it is important to give both monetary and intangible costs equal consideration. That being said, the most quantifiable portion of an economic analysis is the measurable, monetary costs, which is why we highlight these particular expenses first and foremost.

Given the aforementioned methodology of estimating the costs of continuing operations, we project the yearly cost to be around $4,150. When looking at the costs for integrating a new greenhouse as referenced above, we estimate total expenses to be $40,488. With both of these values established, we estimate that it will take just under 10 years to break even on our investment. As we can see in our analysis, it is more cost effective not to move forward with the greenhouse initiative in the short term, but more attractive in the long term. Given the School’s expansion plans and commitment to a sustainable campus, the implementation of a greenhouse would get more and more use for years to come. It should also be noted that the $40,488 value includes the cost of a potential educational space next to the greenhouse. So even though it would take 10 years to break even, there will be greater educational value to LaFarm from the classroom space that will help foster greater human capital and practical knowledge amongst the Lafayette community. The value of this educational aspect may also indirectly contribute returns on the greenhouse investment because it would attract more students to attend Lafayette through an image of enhanced sustainability.

If we were to consider not allocating funds for a classroom space and focus strictly on greenhouse crop production, then the total costs would be closer to $20,500, which would bring the break-even time to be around 5 years. Furthermore, if we consider the monetized value of the time Sarah Edmonds saves by not going The Seed Farm to be around $9,000, this break-even duration would be cut even shorter.

Another intangible factor to consider in our analysis is the environmental cost differential between integrating a greenhouse and continuing to rent. If LaFarm continues to rent greenhouse space as it currently does from The Seed Farm, there would be a significant environmental cost. According to the United States Energy Information Administration, about 19.6 pounds of CO2 are produced from burning a gallon of gasoline. Provided again with the information that The Seed Farm is 30 miles away from LaFarm and Sarah Edmonds makes the trip on average 3 times per week with a 15 MPG van, it can be estimated that roughly 235.2 pounds of CO2 are produced per week, or 12,230.4 pounds per year. On the other hand, LaFarm manager Edmonds would have to walk a few hundred feet to transport the plants. Although this difference does not equate to a specific monetary cost, environmental factors must be taken into account if Lafayette College strives to maintain its commitment to climate control. Considering Lafayette is the only college or university in the Lehigh Valley to have signed the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment, an initiative aimed at reducing greenhouses gases, it would make sense to incur additional expenses to achieve this mission.

What must also not be overlooked is the time that Sarah Edmonds dedicates to traveling out to the Seed Farm each week. The opportunity cost is extremely valuable because Sarah is the LaFarm manager and her time would be more effectively spent staying on-site compared to driving 60 miles round trip. Not only do these constant trips consume unnecessary fuel, but they also inhibit Farmer Sarah’s productivity towards the development of LaFarm.

From both a monetary and environmental perspective, the economic facets of this break-even analysis point to the viable prospect of integrating a greenhouse, provided the appropriation of proper funding.

Next Section: Political Context