LaFarm’s identity and place at Lafayette College has been influenced by the alternative agriculture movement, local food movement, and other campus farm initiatives. Our project, therefore, must be shaped by these contexts as well since it will be integrated within the LaFarm system and become part of its identity. We have determined several ways to connect the faculty, administration, students, and greater Easton community to this project and LaFarm as a whole through these formative contexts.

The main goal of raising chickens on LaFarm is to utilize their natural, soil enriching behaviors to revitalize a section of the field that is depleted from several years of traditional farming practice. LaFarm’s mission statement is on the Lafayette College website:

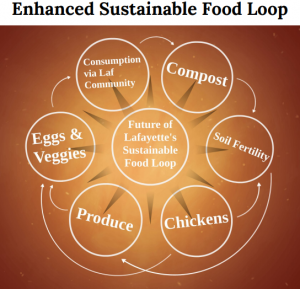

LaFarm is a sustainability initiative at the College and the cornerstone of the Lafayette College Sustainable Food Loop. Our mission is to integrate curriculum and practice in sustainable food and agriculture for the campus community. We grow produce for the dining halls, recycle nutrients from composted food back to the soil, and serve as a laboratory for collaborative student-faculty education and research (LaFarm, n.d.).

Traditional farming methods and chemical fertilizers, therefore, would not fit in with the mission and values of LaFarm and an alternative method must be found. One possible solution that does fit in within the context that LaFarm has established is solar powered mobile chicken coop. According to Alternative Agriculture (Committee on the Role of Alternative Farming Methods in Modern Production Agriculture, National Research Council [NRC], 1989), “The hallmark of an alternative farming approach is not the conventional practices it rejects, but the innovative practice it includes.” Though it is important that LaFarm would be rejecting traditional methods, it is even more crucial that there is innovation. While there is a natural compost process that serves as a fertilizer for much of the current LaFarm area, the innovation of using a solar-powered chicken tractor on a college farm, to fertilize a field that will be used to provide food to dining halls and the surrounding community would be an unprecedented achievement. The chicken tractor is a classic case of alternative systems, which “deliberately integrate and take advantage of naturally occurring beneficial interactions (NRC, 1989).” Lafayette College consistently demonstrates a commitment to constantly improve its stature amongst peers as well as its public image through sustainability (Our Values, n.d.). A chicken tractor could be a staple of the LaFarm and the College’s commitment to sustainability, particularly if it is solar powered. By naturally fertilizing and revitalizing a nutrient-depleted field, the college is not only rejecting conventional chemical fertilizers and embracing alternative energy, but creating an innovative, alternative agricultural solution that could potentially be implemented at other college farm initiatives.

Local food movements attempt to connect food producers and consumers who live and work in the same area (Starr, 2010); LaFarm is a classic example of this movement within our campus community. LaFarm provides vegetables and greens to the dining halls, and though it does not provide one hundred percent of the produce that is consumed (LaFarm, n.d.), it does force students to become a part of the local food movement (whether they know it or not). Local food is an alternative to the normative global food model, which typically utilizes industrial agriculture techniques and modern transportation systems so food can long distances to reach the consumer. By supporting local food movements, consumers and farmers are coming together to promote sustainability and food security within their respective communities (Dunne, Chambers, Giombolini, and Schlegel, 2010). According to the USDA, 7.8 percent of U.S. farms were participating in the local food movement to some degree as of 2012. From 2002 to 2007, the number of farms with direct to consumer (DTC) sales increased 17 percent, and from 2007 to 2012 it increased another 5.5 percent. Additionally, local food sales accounted for an estimated $6.1 billion in 2012; these statistics demonstrate that interest in local food, as well as its productivity, is continuing to rise (Low et al., 2015). Researchers have found that the local food movement is partially characterized by “its use of pleasure (Starr, 2010).” Most participants go out of their way (with their time and money) to contribute to local food, and they do so happily. Many farmers recognize the significant satisfaction they gain from the “sensual material embodiment of ecology and craft” while consumers are able to have a more personal experience through interaction with the farmer (Starr, 2010). Harnessing the joy and satisfaction one can experience through participation in the local food movement will be a key factor in the long term success of not only the chicken tractor project, but LaFarm as a whole.

Local food movements attempt to connect food producers and consumers who live and work in the same area (Starr, 2010); LaFarm is a classic example of this movement within our campus community. LaFarm provides vegetables and greens to the dining halls, and though it does not provide one hundred percent of the produce that is consumed (LaFarm, n.d.), it does force students to become a part of the local food movement (whether they know it or not). Local food is an alternative to the normative global food model, which typically utilizes industrial agriculture techniques and modern transportation systems so food can long distances to reach the consumer. By supporting local food movements, consumers and farmers are coming together to promote sustainability and food security within their respective communities (Dunne, Chambers, Giombolini, and Schlegel, 2010). According to the USDA, 7.8 percent of U.S. farms were participating in the local food movement to some degree as of 2012. From 2002 to 2007, the number of farms with direct to consumer (DTC) sales increased 17 percent, and from 2007 to 2012 it increased another 5.5 percent. Additionally, local food sales accounted for an estimated $6.1 billion in 2012; these statistics demonstrate that interest in local food, as well as its productivity, is continuing to rise (Low et al., 2015). Researchers have found that the local food movement is partially characterized by “its use of pleasure (Starr, 2010).” Most participants go out of their way (with their time and money) to contribute to local food, and they do so happily. Many farmers recognize the significant satisfaction they gain from the “sensual material embodiment of ecology and craft” while consumers are able to have a more personal experience through interaction with the farmer (Starr, 2010). Harnessing the joy and satisfaction one can experience through participation in the local food movement will be a key factor in the long term success of not only the chicken tractor project, but LaFarm as a whole.

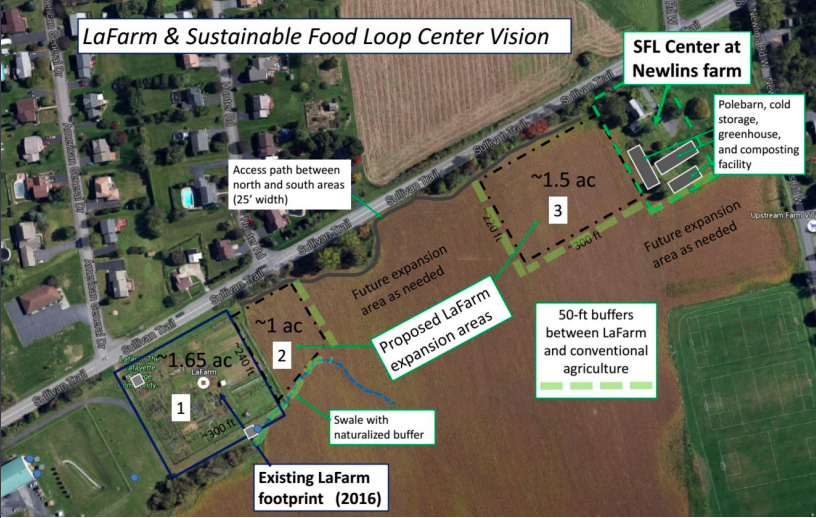

Student farm initiatives on college campuses are not new innovations; the first student farms were established in the early 1900s. With the advent of the counterculture movement in the 1960s and ’70s, college farms became more widespread. Recently, interest in sustainability, local food, and preventing climate change has caused a steep upward trend as more institutions begin their own farm initiatives (Hyslop, 2015). While there is not a singular set of rules or defining factors for successful initiatives, college farms generally share several common characteristics including their interdisciplinary nature and educational opportunities. They help to teach students about their environment, sustainability, and often alternative agricultural methods as well (Hyslop, 2015). LaFarm (Lafayette College Community Garden and Working Farm) was initially conceptualized after a “Corn on the Quad” garden project in 2008; students read and analyzed Michael Pollan’s “Omnivore’s Dilemma,” which sparked conversations about the role of food in our lives and at Lafayette (Edmonds, 2015). The farm began to really take shape in 2009 through the efforts of Jenn Bell (‘11), who eventually became the first Farm Manager in 2012. Through initial funding from the Clinton Foundation and partnerships with the Society of Environmental Engineers and Scientists (SEES) and the Lafayette Environmental Awareness and Protection (LEAP) organizations, Bell set the foundation for what LaFarm has grown into today (LaFarm Archives, n.d.). In 2015, LaFarm was 37,000 square feet (about .85 acres), produced over three thousand pounds of produce, averages three EXCEL scholars, and had over ten part-time student staff annually (Edmonds, 2015). Lafayette College owns the farmland surrounding LaFarm, and is currently looking at several expansion options; this process birthed the idea of using chickens to revitalize the soil in order to make expansion fit within the ideals and goals of LaFarm and Lafayette’s sustainability commitment. The proposed areas of expansion range from one to one and a half acres, pictured below. Through the use of the chicken tractor, LaFarm could increase the amount of production significantly and thus increase the visibility and productivity of the Sustainable Food Loop as a whole.

.

.

Currently, there are no livestock or poultry on LaFarm. In fact, “of the 27 colleges to which Lafayette compares itself, 2 have chickens on their farm (Hogan, Ratsimbazafy, and Ungarini, 2016 ).” Pomona College started a small flock in 2008 for their Animal Husbandry program and Macalester College started a four chicken flock of exotic breeds in 2011 for educational purposes as well (Hogan et al., 2016). At Pomona, the chickens are the responsibility of the Environmental Analysis department and are subject to strict animal welfare standards which are regulated by a national accreditation agency. Student coordinators and volunteers are responsible for the day to day care of the chickens as well; additionally, their farm holds a “Backyard Chicken Basics Workshop” to educate students about how to raise chickens in their own backyards (Pomona College, n.d.). Macalester College, as mentioned above, use their small flock to educate students about sustainable urban landscapes and foodsheds. The chickens are cared for by members of the garden club and the eggs are distributed amongst themselves (MULCH Chickens, n.d.). In addition to revitalizing the field next to Newlin’s Farmhouse, our chickens could serve a secondary educational purpose as well if the College models programs after those at Pomona and Macalester.

Adding chickens into LaFarm would not just change its identity, but would also impact the Sustainable Food Loop as a whole. Lafayette College’s Sustainable Food Loop (SFL) is “the central organizing principle for activity at Lafayette College aimed at pursuing sustainable food and farming practices.” In addition to the produce that LaFarm provides to Bon Appetit Dining Services, Bon Appetit provides LaFarm with organic waste to be used in conjunction with the composting facilities at LaFarm, thus creating the loop (Food & Farm, n.d.). Despite being provided with organic waste, the compost at LaFarm is not enough to re-nourish the soil in the proposed area of expansion, further emphasizing the need for alternative, sustainable methods of revitalization (Edmonds).

Integrating chickens into LaFarm will require more maintenance, oversight, and general labor. At the scale we are proposing, the chickens would require only minutes of care per day in order to feed, water, and collect eggs (Raising Chickens, 2013). However, there are several periodic duties that will require more effort, such as constructing and maintaining the coop if something breaks, as well as cleaning out the coop periodically. Sarah Edmonds, whose official title is “Metzgar Environmental Projects Coordinator and LaFarm Community Garden and Working Farm Manager” lives and works on the farm on a daily basis, and has experience working with chickens in the past. Edmonds does not believe a chicken tractor of the scope that we propose would be a considerable additional burden on her; however, Edmonds will need volunteers to help with all aspects of the chickens when she is unavailable (especially cleaning and maintenance) (Edmonds). This requires significant investment and involvement from students, ideally the commitment would be shared amongst a core group of consistent volunteers. One idea supported by Edmonds and members of the previous chicken study is the possibility of a a LaFarm Living Learning Community (LLC) group, which would be mutually beneficial for the students and Edmonds.(Hogan et al., 2016). A Living Learning Community is a three-person house that is “themed;” residents are expected to create their own learning opportunities and actively participate in the creation of programming centered around their theme. There are several LLCs, but there is a high potential for a group of students to come together and form one related to LaFarm. Currently, there is a “Foodie” themed house, and in the past, there has been a “Botany” house, a “Civic Engagement” house, and a “Social Justice” house; all three relate to themes that surround LaFarm and demonstrate that students are at least interested in the issues that LaFarm attempts to address (Living Learning Community Program, n.d.). These LLCs, in conjunction with the EXCEL scholars, the various volunteer organizations discussed below, and the part-time students that have worked with LaFarm in the past, suggest that finding three students to occupy a LaFarm LLC may not be as far-fetched as we initially believed.

A LaFarm LLC is purely speculative at this time, however there are several volunteer organizations that currently exist and work to help with the operations of LaFarm, as well as general sustainability initiatives around campus. Lafayette Environmental Awareness and Protection (L.E.A.P.) has worked directly with LaFarm in the past, but they are oriented towards promoting awareness of environmental issues through educational public displays (LEAP, n.d.).While L.E.A.P. may not help directly in the chicken tractor operation, they could potentially advertise and promote events relating to the chicken tractor. Delta Upsilon sends volunteers every other Saturday or as needed, and could be an excellent resource for Edmonds to utilize when the coop needs cleaning and maintenance. The Lafayette Food and Farm Cooperative (LaFFCo) works closely with Sarah Edmonds to operate LaFarm; they often volunteer their time to do odd jobs and handiwork around LaFarm and is problem the most central organization to the continued operation of LaFarm. Through communication with Jen Giovanniello, the student contact for LaFFCo, we found that her organization would actually be able to contribute several facets of the chicken tractor. In addition to potentially contributing towards the costs and expressing interest in having LaFFCo help set up the chicken tractor, Giovanniello believes that they could incorporate care into their preexisting volunteer events. Additionally, she mentioned that though she was unsure about interest in a LLC or designated person, the 2017 Environmental Studies Capstone mentioned an EcoRep position that would serve as a student – to – farm liaison, and that perhaps this person could include the chickens in their responsibilities (Giovanniello, 2017). These organizations, especially LaFFCo, would be those that could supply volunteers if the LLC or work-study plan does not work out. These organizations are heavily involved and invested in the LaFarm initiative, and many members could be reinvigorated and excited by the possibility of raising chickens. For the initial construction work, it could be done as part of the engineering curriculum or by a set of volunteers. The Society of Environmental Engineers and Scientists (S.E.E.S.) also works closely with LaFarm and has been heavily involved with the design and implementation of technical systems in the past, especially the composting system (Lafayette College Society, n.d.). S.E.E.S. would be an ideal organization to oversee and perform the construction of the chicken tractor if the College and faculty decide against including the process as a part of the curriculum. The aforementioned volunteer organizations will be crucial in integrating a solar powered chicken tractor socially; the success of the project depends on the willingness of the student body to keep it up and running. The good news is that since we are proposing an initial flock of 25 chickens, Sarah will be able to take care of the chickens daily and there should be more than enough volunteers to help with periodic tasks amongst the previously listed organizations.

Raising chickens at LaFarm could generate more interest, willingness to learn, and volunteers. One way to incentivize faculty, students, and others to be more emotionally invested to the chicken project would be to have chicken “sponsors.” These sponsors could name a chicken, and get periodic updates on their health and activities. Sponsors would be more likely to care about the chickens then the average person, and more predisposed to volunteering at LaFarm. A partnership with a locally owned restaurant or coffee shop, which could advertise “Locally sourced organic eggs from Lafayette’s LaFarm” would create a deeper community connection, in addition to the obvious economic benefits, and is a perfect example of the local food movement coming alive at Lafayette. Admittedly, there are several potential issues with both of these ideas. Chickens are quite prone to predators, and death in general; it is a natural and common occurrence (Edmonds). Chicken sponsors may be excited to sponsor and become involved at first, and then become dismayed when “their” chicken passes away. This could be countered through proper education about chicken farming and perhaps some sort of guarantee (i.e. if your chicken is killed by a predator, you get to name another one for free). Additionally, there are more stringent regulations when using poultry products commercially which could provide a barrier to the restaurant partnership (Edmonds); these will be discussed further in the Policy Context Analysis.

A flock of chickens, raised in a solar powered chicken tractor for their eggs and fertilizer as part of a sustainability initiative, would undoubtedly change the social identity of LaFarm, the Sustainable Food Loop, and Lafayette College by having wide ranging impacts throughout the arenas of the local farm movement, alternative agriculture movement, and college farm initiatives.