Company History

The history of the Dixie Cup began when Lawrence Luellen first became interested in an individual drinking cup in 1907, through a lawyer named Austin M. Pinkham, with whom he shared the same business suite on State Street in Boston. Pinkham had investors who were interested in forming a company to manufacture a flat-folded paper drinking cup which would be delivered by a vending machine and connected to a water cooler. The object was to dispense a pure drink of water in a new, clean, and individual drinking cup. While Luellen saw the potential of such a machine, he concluded that in order for the machine to be successful, it would have to dispense a cup in open form rather than one which would have to be unfolded each time. Luellen conceived of a one-piece pleated cup, made of a circular blank of paper – treated with paraffin to hold the folds in place.

In early 1908, Luellen also began work on a two-piece cup made out of a blank of paper rolled into “frusto-conical” form with a separate bottom piece. He began consultations with patent attorney, Sylvanus Cobb about the patentability of his invention. Luellen also enlisted the assistance of Eugene H. Taylor, an engineer and inventor, of the Taylor Machine Works at Hyde Park, who was successful in devising a machine to manufacture such cups.

In addition to perfecting the cups themselves, Luellen also completed work on a dispensing apparatus in the early part of 1908. Luellen developed a vending machine that for a price of a penny would dispense a cool drink of water in an individual cup. This “Luellen Cup & Water Vendor” was a tall, white porcelain device divided into four parts: a glass jug of water on top of an ice container, a middle section for waste water, and a bottom receptacle for discarded cups. The cup dispenser was attached to the front of the vendor. He came upon the idea of nesting the cups together in a column, or compact form for better handling. Luellen conceived of a flange on the cup so that it might be separated from the adjacent cup.

With these various inventions and a group of investors Luellen incorporated his new company as the American Water Supply Company of New England on April 4, 1908 in the state of Massachusetts. Although Luellen continued to work independently on developing the one-piece, pleated cup, the directors of the company decided that the capital investment for the machine was too high. Instead the company voted to manufacture only the two-piece, smooth-sided cup because of the much lower manufacturing cost.

In the fall of the same year the company also began manufacturing the cup dispenser alone, which sold cups for a penny and were to be installed next to drinking fountains. The first “penny vendors” were made out of brass tubing with a horizontal cylindrical casing made out of heavy cast iron which held the cups. Herman Doehler of the Doehler Die Casting Company of New York was able to make a casing out of a lighter steel which replaced the earlier model.

It was Luellen’s original plan for the cup business to organize a number of local companies having territorial rights under his invention, and the American Water Supply Company of New England was to be the first of these companies with rights to New England only. In an effort to broaden distribution of their products Luellen also organized the American Water Supply Company of New York with Hugh Moore as secretary and treasurer, and the American Water Supply Company of New Jersey in 1908 or 1909 with Moore as the director. Neither of these companies manufactured cups, but sold cups and also the vending apparatus manufactured by the American Water Supply Company of N.E. under license from Luellen’s patent. On February 3, 1909 Moore and Luellen formed the Public Cup Vendor Company incorporated in New York, principally to lease their machines to railroads and railroad stations, and the cups were sold to their customers in bulk. Moore was named treasurer and general manager of the Public Cup Vendor Company. In this company as well as the others Luellen received stock and a salary.

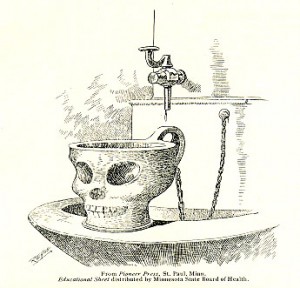

The paper cup business received a boost when the campaign to abolish the public drinking vessel gained several important endorsements. Lafayette biology professor Alvin Davison’s influential study on the contamination present in school drinking cups was published as “Death in School Drinking Cups” in Technical World Magazine in August 1908, and redistributed by the Massachusetts State Board of Health in November 1909. Davison’s experiments were carried out in Easton, Pennsylvania’s public schools.

In a further development in 1909, Kansas passed the first state law to abolish the common drinking cup-the “tin dipper” in public places and the common glasses beside coolers in railroads. The campaign was led by Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine of the Kansas State Board of Health. The publicity given Dr. Crumbine’s campaign and Professor Davison’s survey eventually resulted in state after state passing laws that forbade the use of a common drinking vessel in public places. Railroads were among the first to recognize the benefits to the public of abolishing the common drinking cup, and they provided the American Water Supply Company with the first steady market for its penny vendor. As the use of a common drinking cup was forbidden in places like schools, offices and other public places, the company began to market an apparatus which would dispense the cups for free. In his own campaign against the “tin dipper,” Hugh Moore spoke at the Pure Food Show in Madison Square Garden on the dangers of the common drinking cup on September 23, 1910 and in 1909-1910 published a pamphlet called The Cup Campaigner.

Despite initial success with the territorial companies, Luellen and Moore decided to consolidate the operation into one organization. After an unsuccessful attempt to get new investors, the two men took up quarters at the Waldorf- Astoria Hotel using hotel stationary to impress potential investors. They opened a small account with the Title Guarantee & Trust Company, and operated out of an office in the Wall Street financial district, at 115 Broadway, adjacent to Trinity church. Through a suggestion from Arthur Terry, the treasurer of the bank, they approached Edgar L. Marston, the director of the Trust company. According to Marston, Moore put on quite a show with the vision of instant death on the rim of the common drinking cup. Marston, Terry, and several of their friends, including William T. Graham, president of American Can Company, offered a $200,000 capital investment which allowed the company to establish itself.

On December 15, 1910 the Individual Drinking Cup Company of New York was incorporated in Maine (The company was reorganized and incorporated in New York in 1917, and in the transaction acquired its predecessor). This time Luellen assigned his patents to the new company allowing it to manufacture cups. In turn, he received substantial stock in the company and cash. Moore was secretary, treasurer, general manager and finally president of the new company. The first manufacturing plant was at 118 East 16th Street-a loft space. In 1911, the company headquarters was moved to 220 West 19th Street. The plant originally occupied only one floor (6000 square feet), but eventually expanded to six before the move from New York. The early Dixie team included engineer and production manager Edwin Wessman, Harry Stone, Samuel Graham, Herman Carew, accountant Arthur Lillicrapp, and Cecil Dawson who joined the company to direct Sales.

By 1912 the Individual Drinking Cup Company’s product was called the Health Kup and the company had developed its first semi-automatic machine to produce them. In 1913, a related venture, the Individual Service Company was established to vend towels, soap, deodorizers, and sanitary napkins.

By 1916, more than 100 railroads throughout the country, including the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Lackawanna, The Chicago, Illinois Central, some New York Central lines, as well as the Pullman Company had entered into contracts to sell the Individual Drinking Cup Company’s products. The company soon expanded its market to drug stores and soda fountains. The flu epidemic after World War I put paper cups in even higher demand. Faced with the growing number of companies entering the cup-making business each year, Hugh Moore changed the name of his product in an effort to set it apart from the competition. In 1919 the Health Kup became the Dixie Cup, named for a line of dolls made by Alfred Schindler’s Dixie Doll Company in New York.

The growth of his company made it necessary for Hugh Moore to consider a new location. After approximately ten years in New York City, Moore began to inspect sites in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland, before he took a serious interest in a site located in Easton, Pennsylvania. Peter Burnett, Industrial Agent of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and Thomas Hay, a Lafayette College graduate, and the Secretary of the Board of Trade in Easton first showed Moore thirteen acres on the Lehigh Valley Railroad, on the corner of Washington and Northampton Street, but Moore’s engineers decided that the grade was too steep for railroad access. Moore became interested in a nearby property on the Easton-Bethlehem trolley line-part of a 400 acre farm owned by an Andrew Edelman, who at first refused to sell. It was located at the Southeast corner of Northampton Street at the Eastern & Northern railroad crossing in Wilson Township. Finally Moore bought 7 acres at $3000 an acre. With the support of Hay, Will Haytock, president of the Board of Trade, banker Chester Snyder, Judge James Fox, E.J. Richards, and James V. Bull, and backing from the Guaranty Fund of the Easton Board of Trade, Moore decided to build the new plant in Easton. This new venture was financed with a loan of $280.000 for eleven years from the First National Bank of Easton at 5% interest. White Construction Co. a New York firm was awarded the building contract for a plant of approximately 80,000 square feet of floor space. The plant was completed and opened in 1921 with 78 employees; 28 of whom came to Easton from New York, and the remaining 50 were hired locally the first year. Lawrence Luellen did not move with the company headquarters to Easton, but stayed behind to consult with the branch office in New York.

Dixie’s first great success story after moving to Easton began in 1923, with an idea of merchandising an individual serving of ice cream in a Dixie cup. The company’s first contracts were with Weed’s Ice Cream Company of Allentown and Carry Ice Cream Company of Washington, D.C. to sell a 5oz. cup for ten cents. Although the first experiments were a disaster, the company soon developed a smaller, more rigid 2 1/2 oz.cup that would not absorb moisture, or crumble in the filling process, that would sell for five cents. To develop an adequate filling machine, Mojonnier Brothers, authorities on the engineering of filling devices, created an automatic machine to fill a paper cup with two flavors of ice cream at one time. Ice Cream Dixies earned almost instantaneous consumer acceptance.

The Individual Drinking Cup Company established a plan of franchise which permitted only ice cream manufacturers packing high quality ice cream to use the brand name on the Diamond Design Dixie cup. A Dixie trademarked lid carried the individual ice cream manufacturers identification.

An accompanying “Dixie Circus,” a highly successful radio show that aired every Friday night on NBC and later reappeared on CBS radio helped to make the Ice Cream Dixie a household name. In addition to radio, Dixies were also advertised in trade magazines, newspapers, and national consumer magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, Liberty, and Good Housekeeping.

Beginning in 1930, the Individual Drinking Cup Company also introduced a highly successful program by which children collected Dixie lids to receive “Premiums,” beginning with illustrations of their favored Dixie Circus characters, and then Hollywood stars, sports personalities, and in support of the war effort in the 1940s, scenes depicting United States and United Nations forces in action.

Spurred on by the success of the Ice Cream Dixie franchise program, a new line of Pac-Kup containers, and an expanding soda fountain market allowed for continued growth during the Depression years. The Individual Drinking Cup Co. merged with the Vortex Cup Company of Chicago in 1936, bringing that company’s headquarters building in Chicago and its cone-shaped cups, originated by David Curtin in 1912, sundae dishes and a dry-waxing process into Dixie domain. The new company was called the Dixie-Vortex Company, until 1943, when it became the Dixie Cup Company. The success of Dixie products during World War II gave the paper cup business even greater prominence. Dixie Cups and a newly developed portable watertank-cup dispenser were delivered on a priority basis to the Armed Forces, the Red Cross, and war industries.

Along with many other industries, Dixie witnessed considerable growth after the war. Dixie collaborated with Coca Cola in 1946 to market a liquid vendor, introduced the enormously successful “Home Line” in 1949, and not deterred by unsuccessful attempts in the 1930s and 1940s, came out with a popular Brew Master Beer Dixie in 1950. In addition to numerous expansions to its existing plants in Easton, Chicago, and Darlington, the company acquired the C.H. Cowdrey Machine Works (1946) in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, which had manufactured Dixie machines since 1919. The company also expanded to Fort Smith, Arkansas (1947), Brampton, Ontario (1949), Anaheim, California (1952), and Lexington, Kentucky (1958). In addition, the Kleen Products Division of the Modena Paper Mills, located in North Wales, Pennsylvania, became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Dixie Cup Company on April 28, 1957.

After considering numerous companies during the 1950s, including General Foods Corporation and the Scott Paper Company, Dixie approved a merger with American Can Company in 1957. Although Moore stepped down as an officer of the company, he continued to serve American Can Company as a consultant to its Dixie Cup Division. Clarence L. Van Schaick continued as vice-president and general manager of the Dixie Cup Division with its main office in Easton, Pennsylvania. Under the direction of American Can Co. the Dixie Division continued its growth and development of new products, including “Mira-Glaze” cups and dishes in 1959. In 1982, American Can was acquired by the James River Corporation of Virginia. The James River Corporation changed its name to the Fort James Corporation in 1997. Dixie Cup is currently a product division of Georgia-Pacific, a subsidiary of Koch Industries.