Introduction

Corpus is a collection of written texts that mainly focus on a particular author or subject. In this paper, I will discover and analyze the language usage in economic journals via the use of corpus. Exploring linguistics in economics helps students better understand relevant articles in the future. In addition, I will compare the difference in vocabulary and language used in journals that were published in 2012 and between late 2021 and the beginning of 2022, which is almost a ten years period. It explores how the choice of words in the economy will differ within ten years. I chose this topic because I want to know the similarities and differences linguistics used within ten years. I will mainly discuss four research questions based on eight articles to comprehend the economy better.

Research Questions

There are four research questions that I am interested in from these eight articles. The following questions will be investigated: (1) How often do the terms “risk” and “risky” appear in the articles from 2012 and the articles from 2022? From the results, which year the article published has more words of “risk” and “risky”? (2) What are the percentages of Academic Word List (AWL), General Service List (GSL) words from articles in 2012 and 2022? (3) What are the top-5 common phrases that appeared after “risk” from the article in 2012 and 2022? What do the results show about the differences between comparing articles from 2012 and 2022? (4) Are first-person pronouns used in these eight journals? If yes, what are the percentages of first-person pronouns within articles from different years? Comparing the articles from 2012 and 2022, which year is the article published more subjective?

Expectations

Before I use “AntConc” to analyze the data from articles, some expectations correspond with four research questions. For the first question, I expect more words of “risk” and “risky” in articles from 2022 because there are more risks through the development of society, and every investment will take risks. In our discussion, the percentage of AWL would be about 8% to 10%, and that of GSL is about 75%. I believe that our expectation percentage may be higher than the actual ratios of AWL and GSL.

However, these percentages will not be too low regardless of the articles from 2012 or the reports from 2022. For the third question, I cannot make specific assumptions about the top-5 common phrases after “risk” in all eight articles because there are different risks. But I am sure that the top-5 common phrases after “risk” will be distinct compared to articles in 2012 and 2022. In the last question, I trust that these articles will use first-person nouns because authors will express their perspectives with low percentages within the articles. Comparing the articles from 2012 and 2022, I believe that the articles in 2012 have more first-person nouns than those in 2022 because people pursue more objective information nowadays.

Methods

Research Procedure

I spent a lot of time collecting articles for the corpus because it was hard to find the same topics from reports in 2012 and 2022. But it was a necessary and helpful step for creating a corpus. I went to Lafayette College’s online library to find articles in the economic field. I clicked on “Catalog” and selected “Journal Title” from the dropdown menu. I searched “American Economic Review” directly in the search box. Before a corpus was composed, I downloaded “AntConc,” an application that analyzes the corpus.

I watched tutorials online and learned specific techniques during classes. After I downloaded this software program, I put the articles from 2012 and 2022 into “AntConc,” respectively. Next, I used functions in “AntConc” to collect data for answering my four research questions. In this case, I used these data to compare with my expectations, which I made before, and had a conclusion.

Corpus Description

In this project, I chose eight articles from “American Economic Review,” four of them were from 2012, two of them were from late 2021, and the other two were from the beginning of 2022. This is because I wrote this paper at the beginning of 2022, and there are not many relevant items about adverse selection and moral hazard. To have a clear and straightforward paper, I will only write the term “articles in 2022” to include all 2021 and 2022 in this paper. The academic journal “American Economic Review” is a monthly peer-reviewed journal published since 1911. There is no doubt that this journal is one of the distinguished journals in the economic field. Since it will release articles every month, there are many reports I can find there, which is why I choose this journal. Because I hope that the data from articles will be more accurate and objective, I decided on the same topics from the articles in 2012 and 2022. In this case, these articles will talk about one specific thing and have the same word and knowledge, which will help do the corpus.

Research Instruments

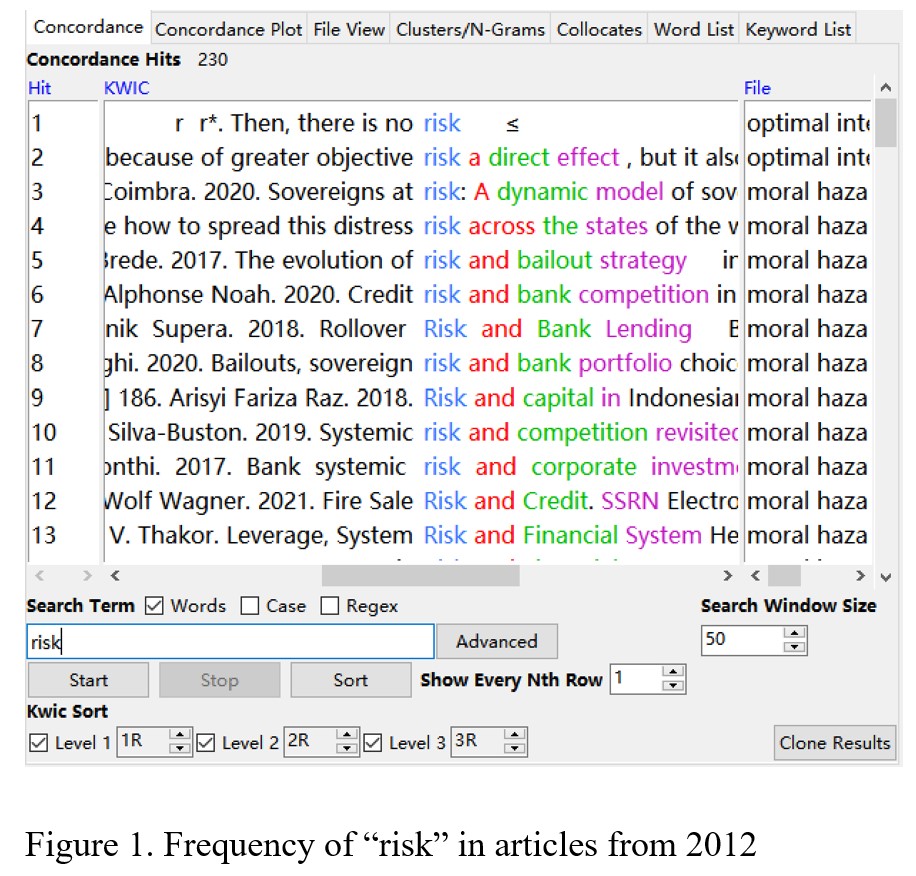

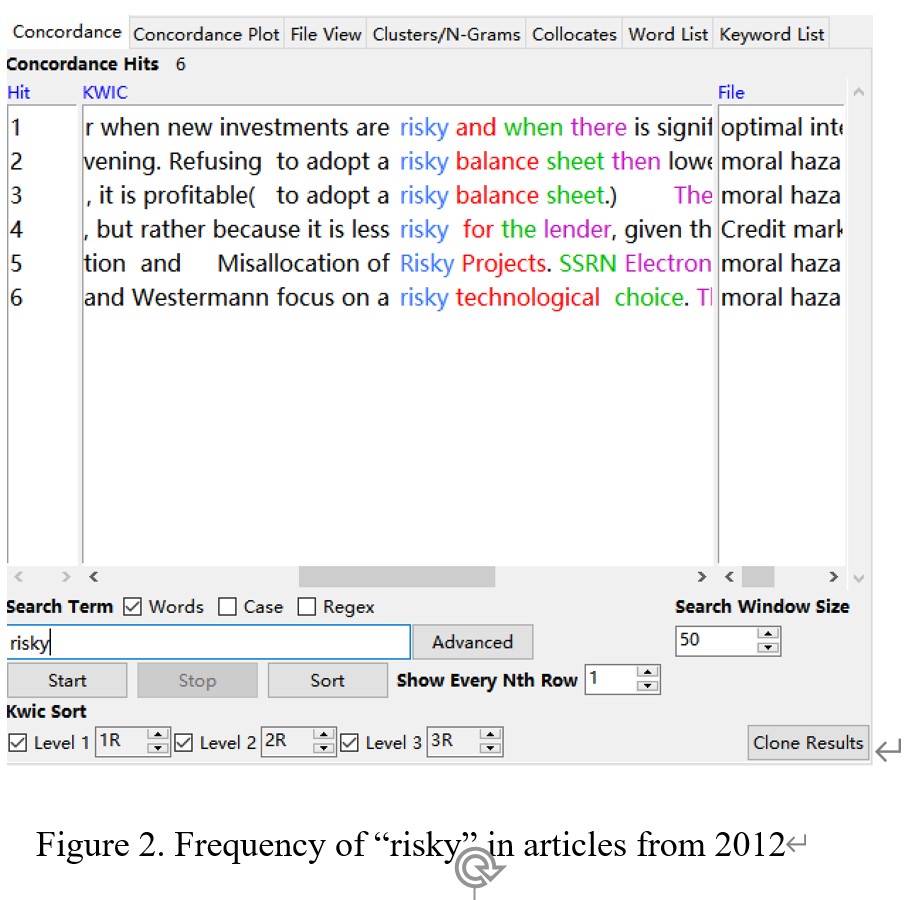

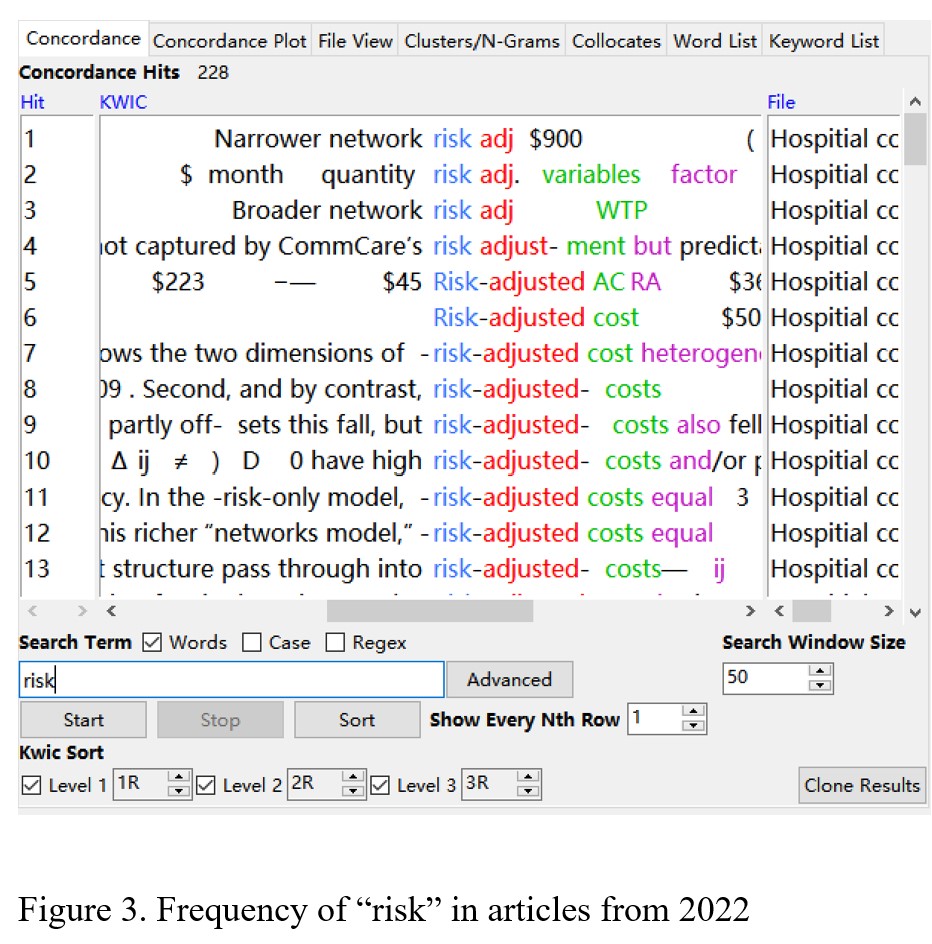

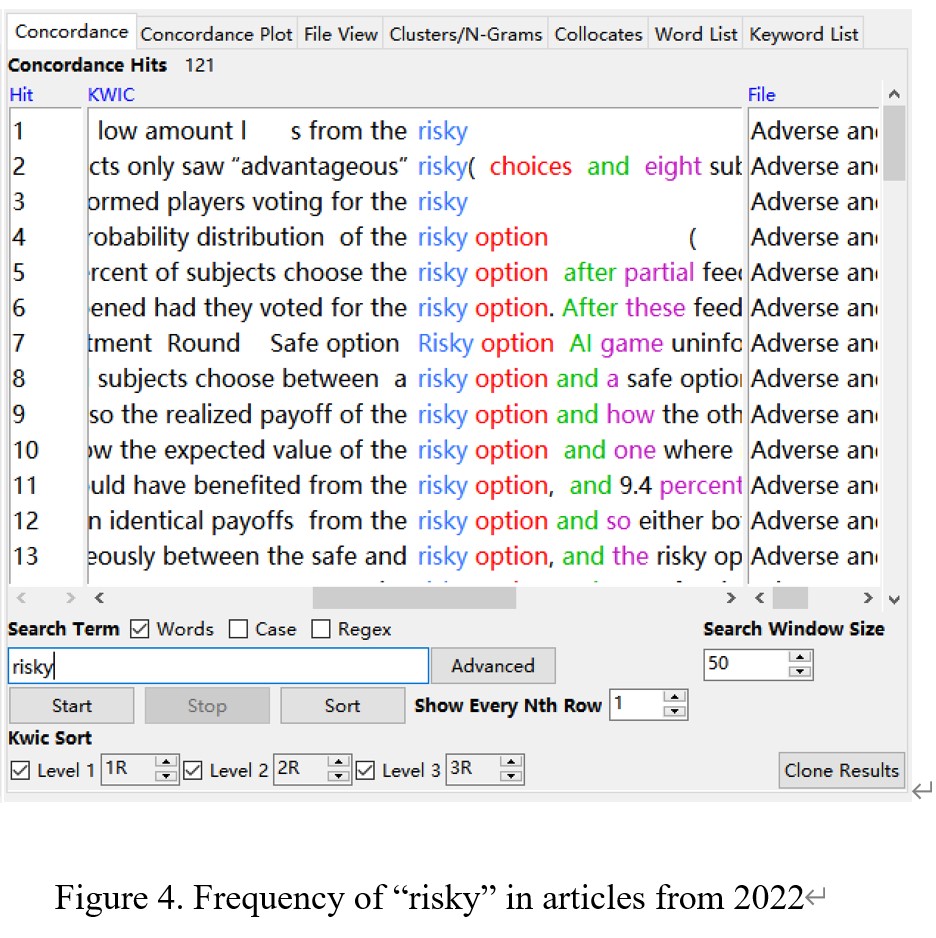

During the research, I will use several tools and functions in AntConc to answer each research question I asked. In the first research question, I used the Concordance tool to search for the term “risk” and “risky” in both articles from 2012 and 2022. After I typed these words in the input box, I clicked “start” to process. Approaching the second research, I used the Word List tool. At first, I clicked “start” in the Word List tool to know the word tokens in articles from 2012 and 2022. I downloaded the documents of AWL and GSL from the google drive that Professor shared with me to my computer. Then, I put these documents into the Word List tool via the “Tool Preferences” settings separately. In the “Tool Preferences” settings, I clicked “Word List” first and then clicked “Use specific words below”. After that, I uploaded the documents of AWL and GSL in the Word List function to know how many AWL and GSL words these articles had, respectively. In this case, I calculated the percentage for the total word tokens in AWL and GSL words, respectively, divided by the total word tokens in articles. In the third research question, I used the “Cluster/N-Grams” for articles from 2012 and 2022. I typed the term “risk” in the search box and clicked “start.” Moving on to the last question, I used the “Concordance Plot” tool. At first, I clicked “Advanced” for setting the first-person pronouns. The first-person pronouns I put in both articles from 2012 and 2022 included we, me, us, my, mine, our, ours, myself, and ourselves. I did not put the first-person pronoun “I” to search because there is a variable “i” or “I” in equations in economic articles. In this case, it could confound the result of first-person pronouns. After that, I calculated the percentage for the total number of first-person pronouns divided by the total word tokens into articles.

Findings and Discussion

After the results from AntConc, each research question can be solved and discussed.

The outcome of the first research question shows that the term “risk” appears 230 times in the articles from 2012 and appears 228 times in the articles from 2022 (shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3). In addition, it displays that the term “risky” appears six times in the articles from 2012 and appears 121 times in the articles from 2022 (shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4). The results show that the articles in 2012 have more the word “risk” than the articles from 2022, and the articles from 2022 have more the word “risky” than the articles from 2012. To be more specific, the term “risk” in the articles from 2012 is only two more than that in the articles from 2022. Furthermore, the word “risky” in the articles from 2022 shows 115 times more than that in the articles from 2012.

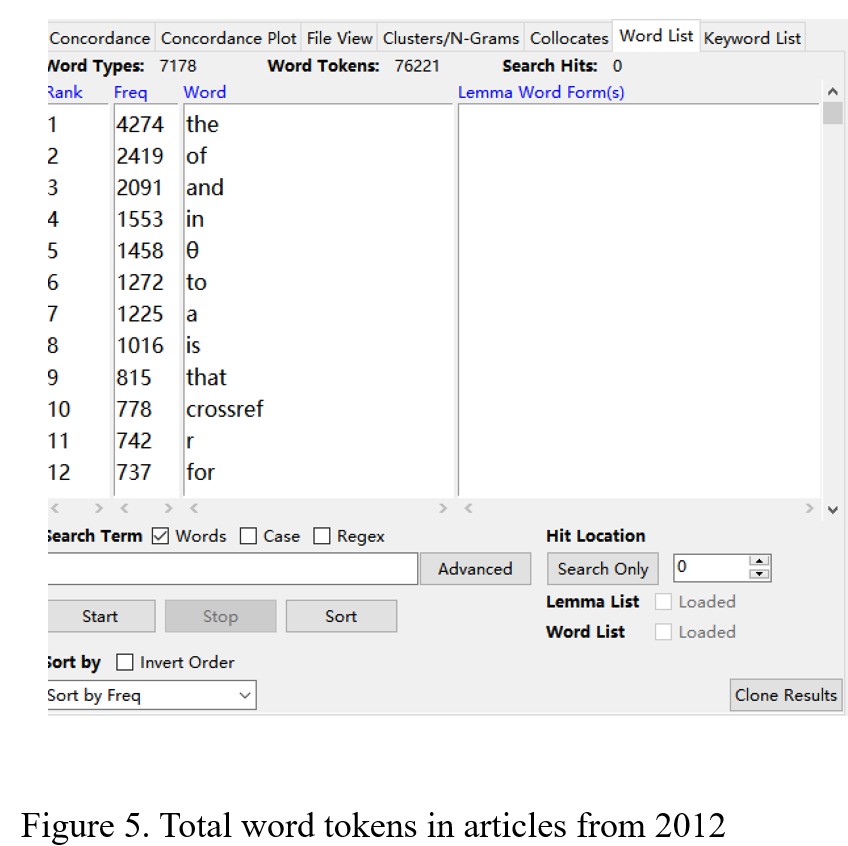

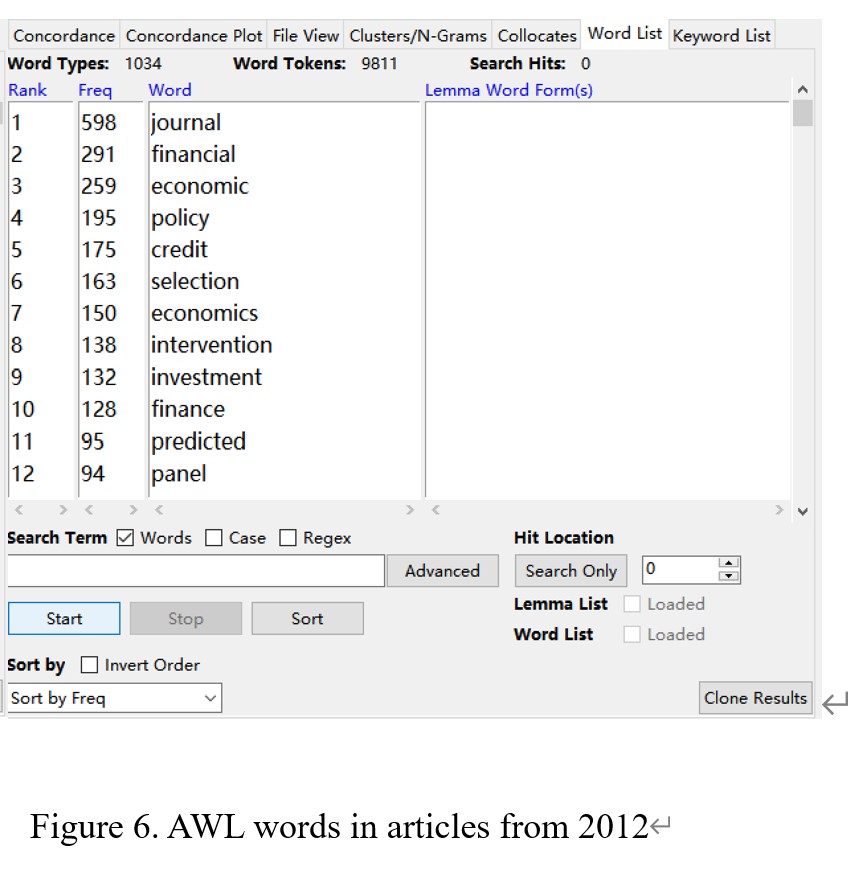

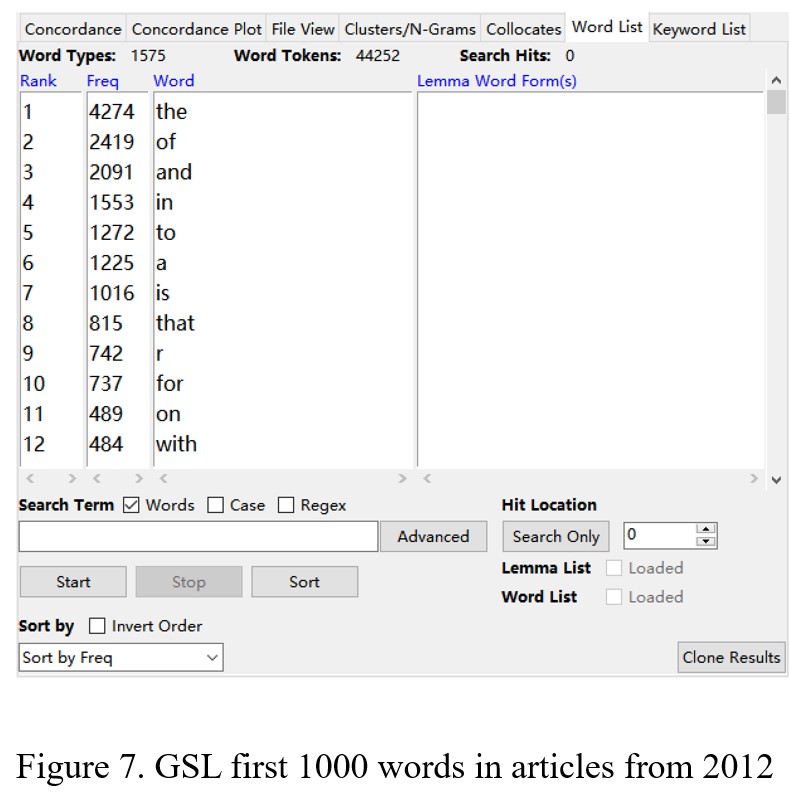

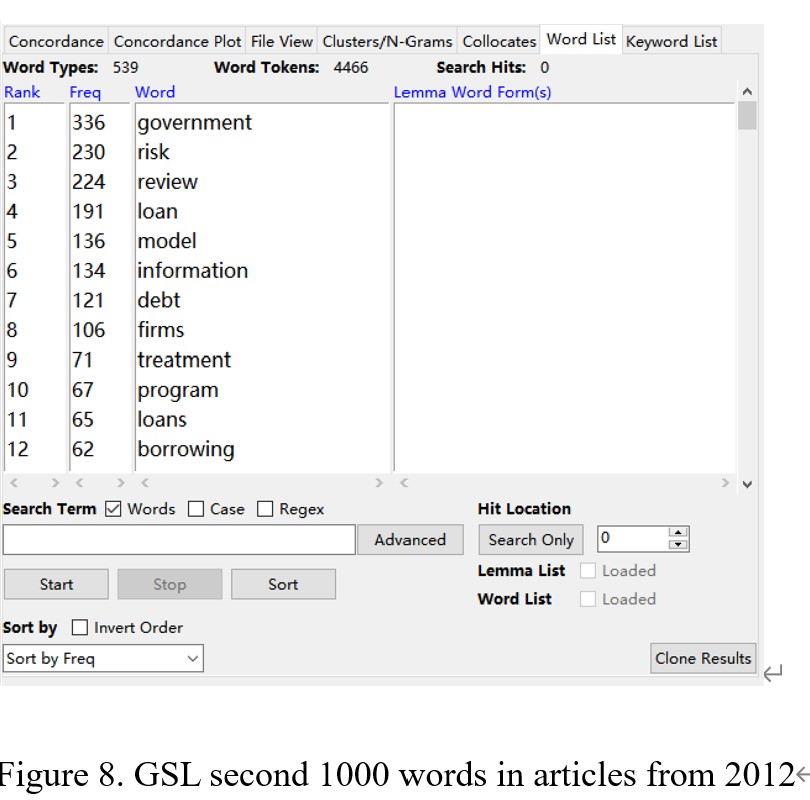

Figure 5 shows that the total number of word tokens in the articles from 2012 is 76221, and the number of word types is 7178. There are 9811 words from AWL, 44252 words from the first 1000 words in GSL, and 4466 words from the second words in GSL (Figure 6, Figure 7, and Figure 8). By calculating, the percentage of AWL in the articles from 2012 is 12.8%, and the rate of GSL is 63.9%. Thus, the percentage of AWL is higher than the standard percentage, and the percentage of GSL is lower than the ideal portion.

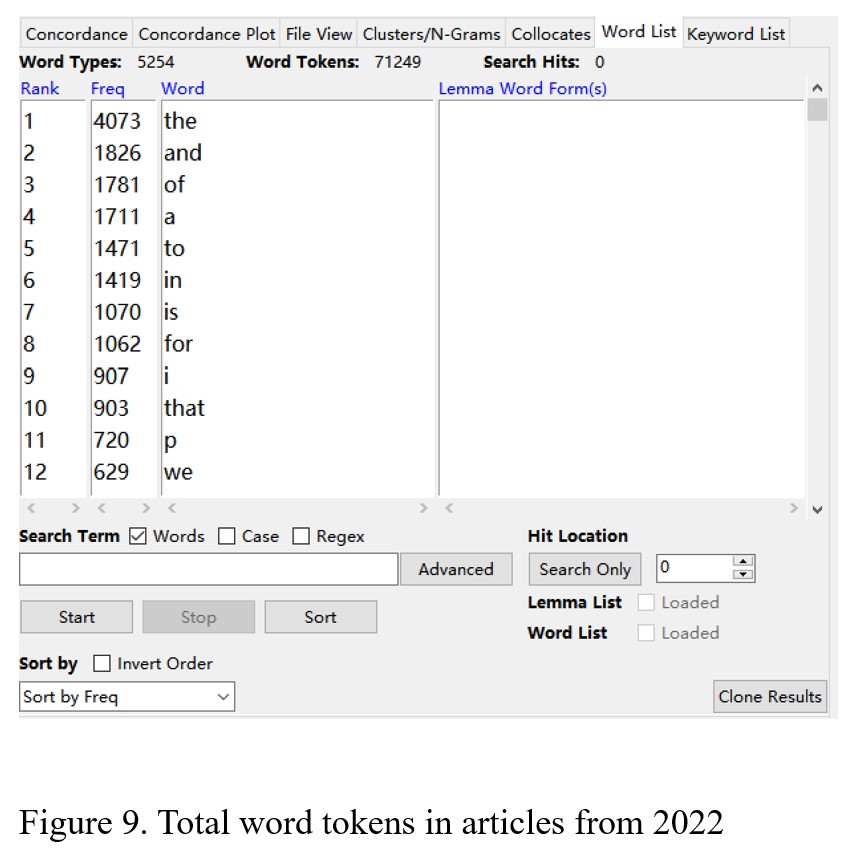

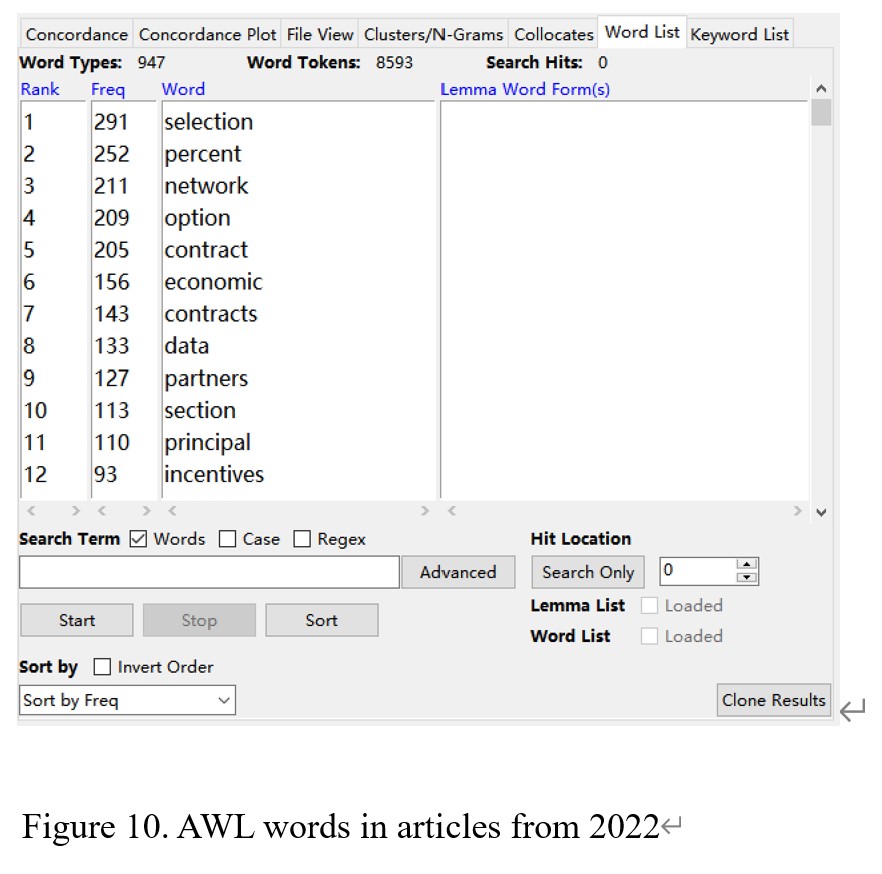

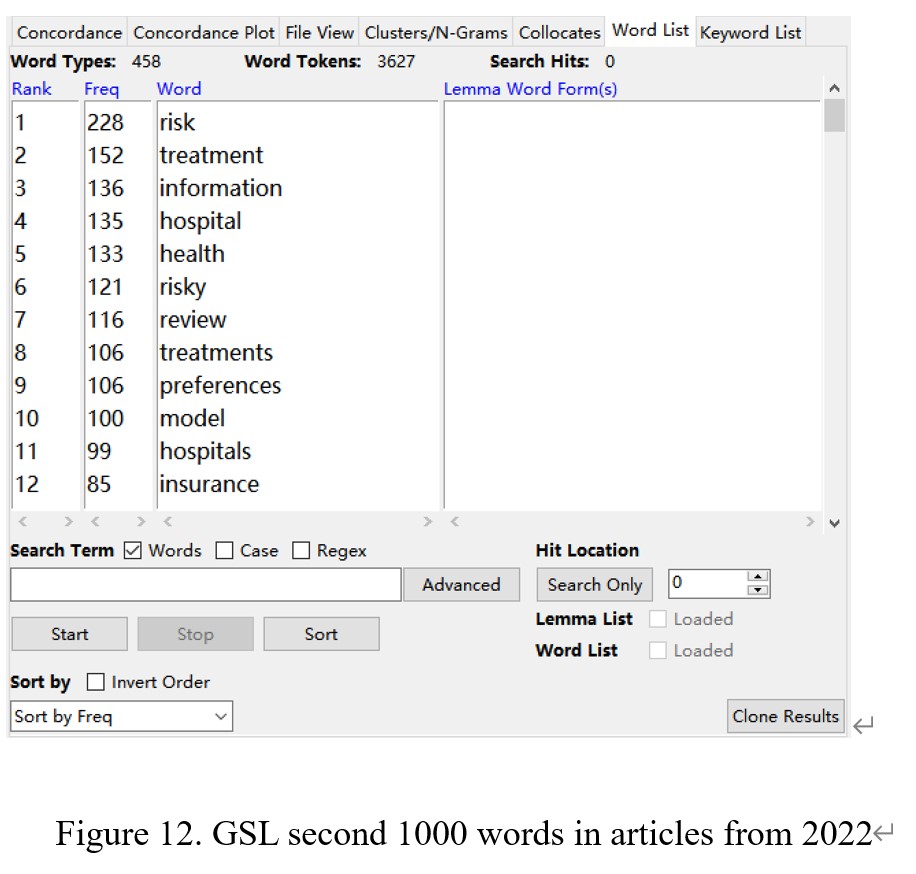

As shown in Figure 9, the total number of word tokens is 71249, and the number of word types is 5254 in the articles from 2022. There are 8593 words that belong to AWL, 48187 words from the first 1000 words in GSL, and 3627 words from the second 1000 words in GSL (see Figure 10, Figure 11, and Figure 12). After calculating, I found that the percentage of AWL in the articles from 2022 is 12%, and the portion of GSL is 72.7%. In this case, the percentage of AWL meets the standard ratio, and the rate of GSL is lower than the ideal portion.

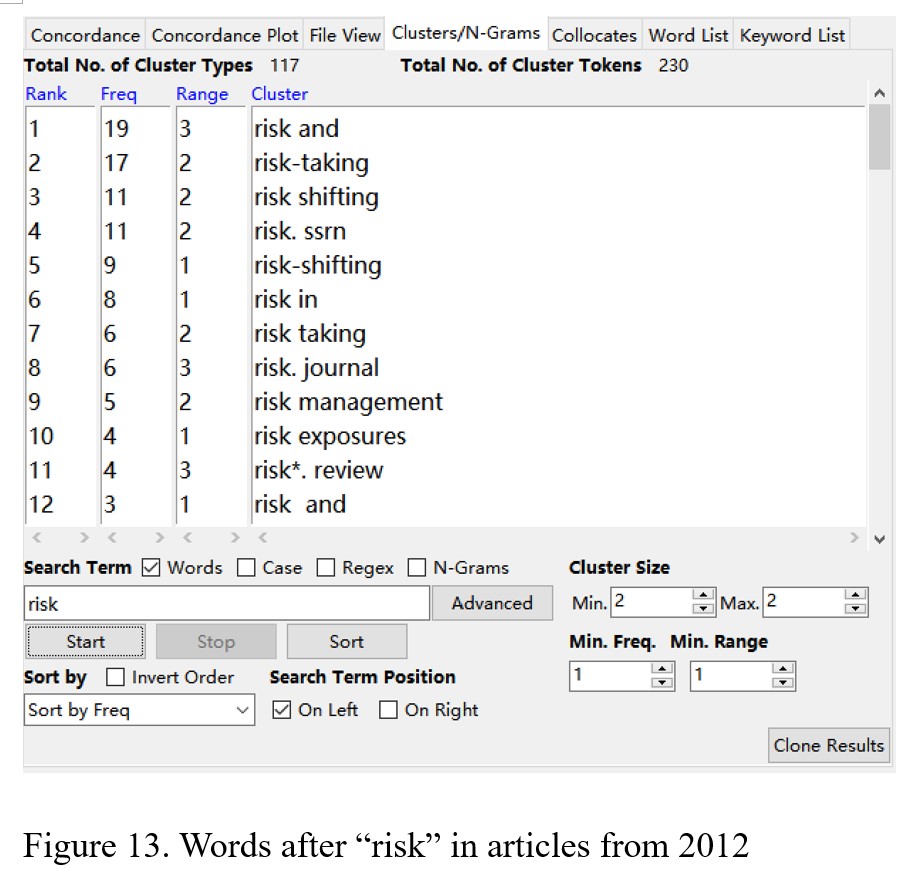

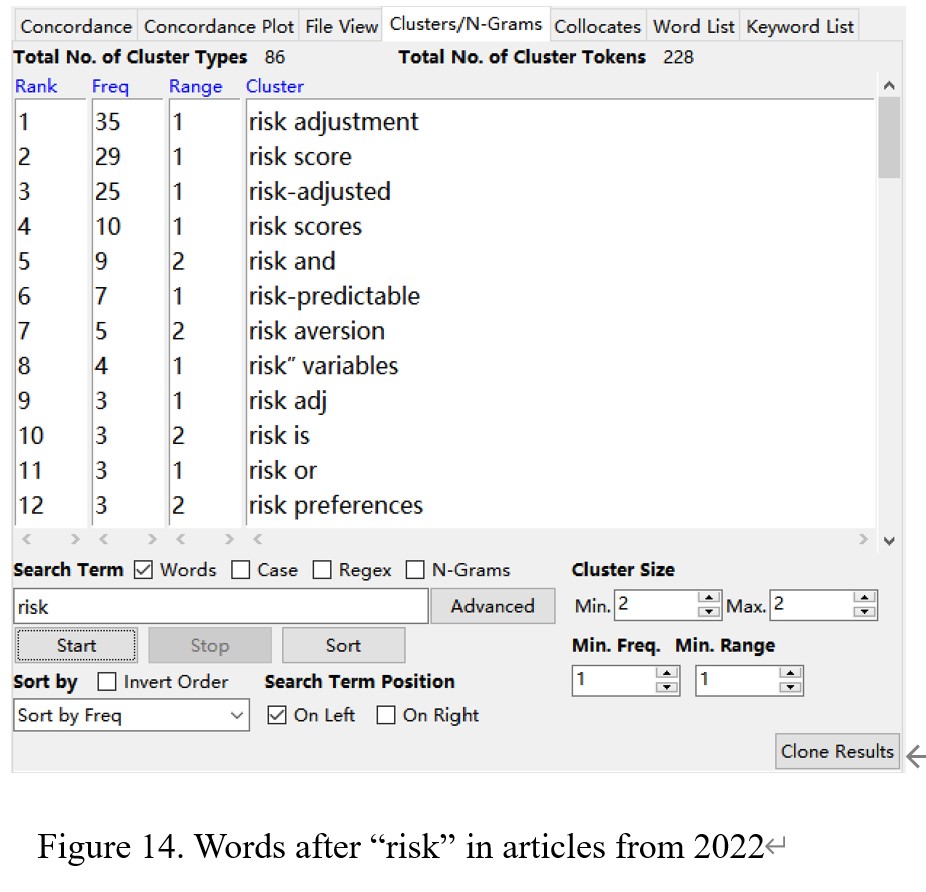

It seems that the top-5 common phrases that appeared with “risk” from the articles in 2012 are “risk and,” “risk-taking,” “risk shifting,” “risk. ssrn”, and “risk-shifting,” as shown in Figure 13. The frequency of each common phrase, respectively, are 19, 17, 11, 11, and 9. From the articles in 2022 in Figure 14, it indicates that the top-5 common phrases with “risk” are “risk adjustment,” “risk score,” “risk-adjusted,” “risk scores,” and “risk and.” The frequency of each common phrase, separately, are 35, 29, 25. 10, and 9. Almost all five common phrases are different between the articles in 2012 and 2022.

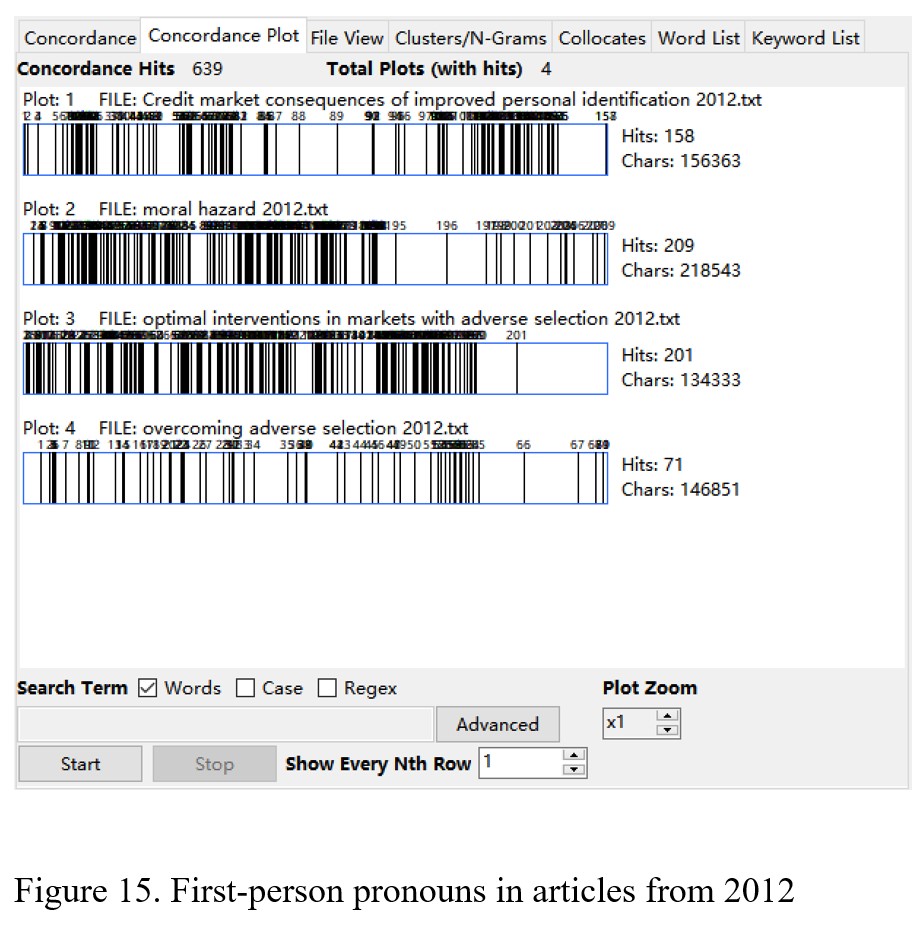

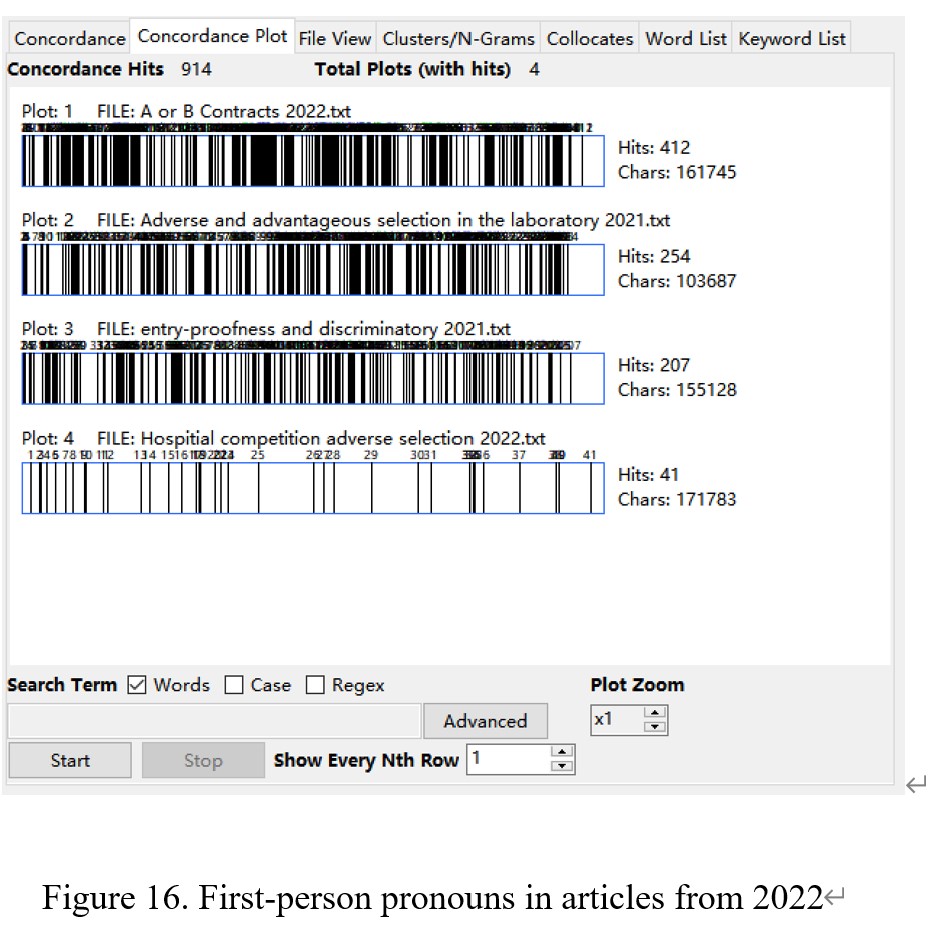

From the results in Figure 15 and Figure 16, all eight articles from 2012 and 2022 have first-person pronouns. There are 639 words that related to first-person pronouns in the articles from 2012. Furthermore, there are 914 words about first-person pronouns in the reports from 2022. As I talked about the word tokens in the second research question, the percentage of first-person pronouns in the articles from 2012 is 0.83%, and the rate of first-person pronouns in the reports from 2022 is 1.28%. In this case, the articles in 2012 are more objective, and the articles in 2022 are more subjective.

Conclusion

Compared with my expectation that there are more words of “risk” and “risky” in articles from 2022, the results from the first research question show different conclusions. The articles in 2012 have more words of “risk,” and the articles in 2022 have more “risky” words. However, the words “risky” in the articles in 2022 appear much more often than in the articles in 2012. In this case, it still can reflect more risks nowadays. In the second research question, I expected that the actual percentages of AWL and GSL are lower than the standard ratios. The answers to this question have some differences. The percentages of AWL in articles from 2012 and 2022 are both higher than the typical percentages. However, the rates of GSL in articles from 2012 and 2022 are both lower than the standard percentage. Although I did not give specific common phrases after “risk” in the third research question, I was in the correct direction. The results show that the top-5 common phrases after “risk” are almost different between the articles in 2012 and 2022. There is only one common phrase that is the same: “risk and,” which is not a specific vocabulary in the economic field. In this case, I believe that it is common in all articles. I expected that there are first-person pronouns in eight articles, and the articles in 2012 will have more first-person pronouns than those in 2022. The data shows that the eight articles all have first-person pronouns, which I already expected. But, I was surprised that there are more first-person pronouns in the articles of 2022 than those in the articles of 2012. To find the reason for that, I thought that authors wanted to share their perspectives more in articles nowadays.

In this project, I learned the word used in economic articles and the differences between the articles in 2012 and 2022. In addition, I learned how to use the software “AntConc.” With the help of AntConc, the four research questions can be solved with data and compared with the expectations that I claimed before.

Furthermore, there are two limitations to this project. First of all, I did not remove the numerical, and mathematical symbols from these texts. In addition, I ignored the word “I” in the first-person pronouns. I talked about the reason for doing this in the Method part. To solve these limitations for future research, the suitable solution is to delete equations in articles before doing AntConc.

Works Cited

Ali, S. Nageeb, et al. “Adverse and Advantageous Selection in the Laboratory.” American Economic Review, vol. 111, no. 7, 2021, pp. 2152–2178., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200304.

Attar, Andrea, et al. “Entry-Proofness and Discriminatory Pricing under Adverse Selection.” American Economic Review, vol. 111, no. 8, 2021, pp. 2623–2659., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190189.

Farhi, Emmanuel, and Jean Tirole. “Collective Moral Hazard, Maturity Mismatch, and Systemic Bailouts.” American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 1, 2012, pp. 60–93., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.1.60.

Georgiadis, George, and Michael Powell. “A/B Contracts.” American Economic Review, vol. 112, no. 1, 2022, pp. 267–303., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200732.

Giné, Xavier, et al. “Credit Market Consequences of Improved Personal Identification: Field Experimental Evidence from Malawi.” American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 6, 2012, pp. 2923–2954., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.2923.

Philippon, Thomas, and Vasiliki Skreta. “Optimal Interventions in Markets with Adverse Selection.” American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–28., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.1.1.

Shepard, Mark. “Hospital Network Competition and Adverse Selection: Evidence from the Massachusetts Health Insurance Exchange.” American Economic Review, vol. 112, no. 2, 2022, pp. 578–615., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20201453.

Tirole, Jean. “Overcoming Adverse Selection: How Public Intervention Can Restore Market Functioning.” American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 1, 2012, pp. 29–

59., https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.1.29.