How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America

Acclaimed author, historian, and PBS documentarian Donald L. Miller brilliantly evokes all the exhilaration, glamour, and significance of one of the most creative and consequential moments in American cultural history in SUPREME CITY: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America (Simon & Schuster; May 6, 2014; $37.50). Chronicling the era immortalized by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Miller reveals how revolutionary developments in technology, architecture, the arts, sports, communications, engineering, transportation, entertainment, retail, fashion, and more merged with the unbounded ambitions of a diverse group of out-of-towners to shape the contours of twentieth-century America. Miller’s book on Chicago, City of the Century, was the basis for an award-winning PBS series of the same name, and another PBS documentary, the Emmy-nominated Victory in the Pacific, was based in part on his book D-Days in the Pacific. HBO is currently making his book Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany into a miniseries produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks.

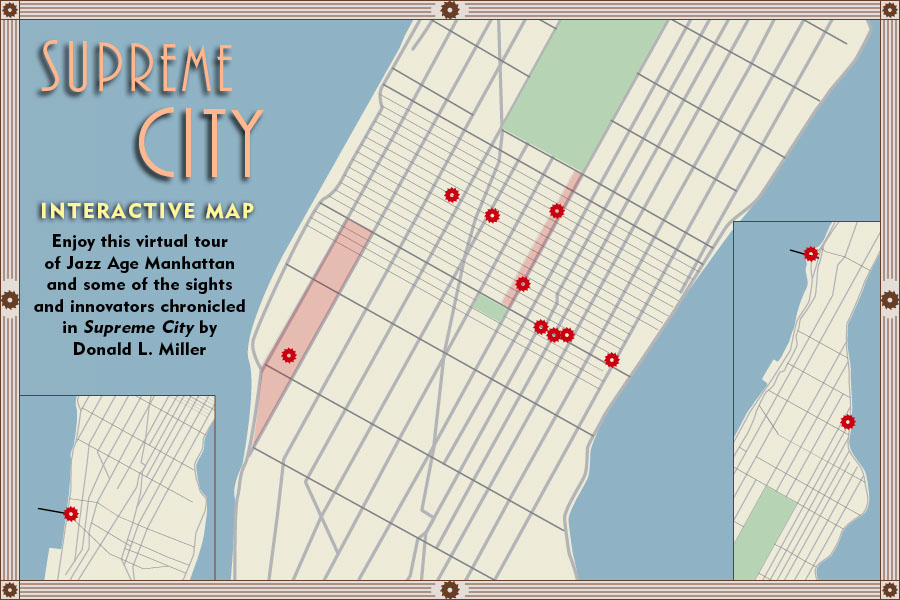

The framework of Miller’s dazzling, multi-faceted narrative is the transformation of Midtown Manhattan in the 1920s into the entertainment and communications center of New York – and America – and a business district that rivaled Wall Street in power and impact. This transformation began in earnest with the completion of the magnificent Grand Central Terminal in 1913, the magnet project for the reconstruction of Midtown, and reached its apogee in 1927, the year the new NBC radio network went national, the opulent Roxy and Ziegfeld theatres opened, and real estate prince Fred F. French completed his eponymous Art Deco skyscraper on Fifth Avenue.

As Miller recounts, Grand Central became the core of one of the greatest building booms in the history of cities: more than fifty skyscrapers were erected in Midtown, and three of the most impressive of them – the Chanin Building, the Daily News Building, and the Chrysler Building – went up in the “Valley of the Giants” near the new transportation hub. The railroad tracks that ran north from Grand Central, which for years had bisected Manhattan with steel, noise, and soot, were covered over so that modern Park Avenue could be created as an elegant thoroughfare to match the grand boulevards of Vienna and Paris. The physical transformation ushered in a social one, as old-money families abandoned their Fifth Avenue mansions for penthouse apartments on Manhattan’s new Street of Dreams, where they were joined by thousands of new millionaires.

Testing the limits of the possible

Lending a fresh approach to a time and place of perennial interest, Miller vividly re-imagines New York City as it was then, telling his fascinating story through the lives of his characters, unsure of what lay ahead or of posterity’s judgment. Hailing from every corner of the nation, and in many cases from abroad, they were inspired by their adopted city to test the limits of the possible. Walter Chrysler, of Wamego, Kansas, personally paid for the construction of the iconic skyscraper named for his family and corporation. Clifford Holland of Massachusetts designed the indispensable tunnel – a marvel of engineering – that bears his name, while Swiss-born engineer Othmar Ammann designed and built the equally impressive George Washington Bridge, and Raymond Hood of Rhode Island became one of the world’s most celebrated skyscraper architects.

Meanwhile, Times Square and Broadway became the Movie Mecca of America. The Great White Way was lined with movie palaces of Oriental splendor, the most luxurious of them the Roxy, built by Samuel (Roxy) Rothafel, a former bartender from the Pennsylvania coalfields. Live theater continued to thrive, much of it produced by impresario Florenz “Flo” Ziegfeld, a former carnival con man from Chicago. But it was rapidly being overtaken in reach and popularity by new forms of electronic entertainment, both recorded and live.

Rich playboy William Paley, from Philadelphia, founded the CBS radio network in rivalry with NBC’s David Sarnoff, a Russian immigrant who couldn’t speak a word of English when he arrived in New York with his impoverished parents. Paley’s network broadcast the hot jazz of a virtuoso young composer and bandleader from Washington, D.C., Duke Ellington, who aptly called Manhattan “the center of everything.” CBS transmitted Ellington’s orchestra out to the rest of the country direct from Harlem’s Cotton Club, owned by bootlegger Owney “The Killer” Madden, an immigrant from England’s Dickensian slums. Along with Frank Costello, of Calabria, Italy, and “Big Bill” Dwyer from Manhattan’s turbulent Hell’s Kitchen, he formed a Prohibition-era bootlegging syndicate that became the prototype for the Mafia of “Lucky” Luciano and Meyer Lansky.

New York’s sports world, heavily publicized by The Daily News, America’s first tabloid newspaper, was teeming with larger-than-life figures like Babe Ruth, from Baltimore’s waterfront slums, Jack Dempsey, the Mauler from Manassa, Colorado, Gene Tunney, a local hero from Greenwich Village, and Tex Rickard, boxing’s foremost promoter, from the Alaska gold fields. Over on Fifth Avenue, Helena Rubinstein, raised in a Polish ghetto, and Elizabeth Arden, a Canadian farm girl, invented the modern cosmetics industry in their elegant Fifth Avenue salons.

On a Midtown street lined with speakeasies, Horace Liveright, a Philadelphia stockbroker, formed a publishing house that revolutionized the way books were sold. Two of his young staffers, Richard Simon and Bennett Cerf, co-founded Simon & Schuster and Random House, respectively. E. B. White, another out-of-towner who famously observed that outsiders often embrace New York “with the intense excitement of first love,” wrote for a sophisticated new magazine called The New Yorker, whose radiant, wild-living columnist, Lois Long, the archetypical Jazz Age flapper, covered Manhattan’s flourishing night club scene under the pseudonym “Lipstick.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of 1927, the year of Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight from New York to Paris, “the tempo of the city had changed sharply. . . . The parties were bigger and the buildings were higher, the morals were looser and the liquor was cheaper. . . . The Jazz Age now raced along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money.” In 1927, the year Miller features in Supreme City, it seemed unimaginable that the greatest building boom in modern history would soon collapse with shocking suddenness along with the stock market, and that stylish, high-living Jimmy Walker, the city’s immensely popular mayor, would be brought low by charges of corruption and forced to resign. But until that moment, what a ride it was.

Packed with new information and perspectives that will intrigue, delight, and surprise even the most informed readers, SUPREME CITY is the transfixing, definitive account of a climactic moment in New York and American history, when commerce and culture embraced each other as never before. Donald L. Miller brings to vibrant life a band of wildly ambitious outsiders who saw fresh opportunities in Manhattan and with their extraordinary achievements transformed first the city, then the country.

The Rise of the Jazz Age

History in Five

Lecture at the Skyscraper Museum June 24, 2014