Soldier. Scholar. Revolutionary. Hero of Two Worlds.

If there was a rock star of the American Revolution, it was Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834). Young, handsome, rich and brave, the French aristocrat who defied his own king to support the cause of freedom in the New World became a renowned statesman whose support for individual rights made him a beloved and respected figure on two continents.

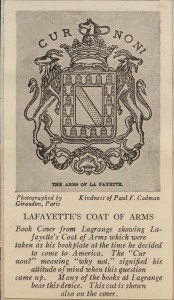

Born into a family with illustrious ancestors on both sides, Lafayette at first appeared destined for a typical aristocratic, military career. He had other ideas. He adopted the motto “Cur Non” (“Why Not?”) for his coat of arms and joined the Freemasons in 1775. Two years later, lured by the image of a nation fighting for liberty, he bought a ship at the age of 19 and sailed to America to volunteer in General George Washington’s army.

Born into a family with illustrious ancestors on both sides, Lafayette at first appeared destined for a typical aristocratic, military career. He had other ideas. He adopted the motto “Cur Non” (“Why Not?”) for his coat of arms and joined the Freemasons in 1775. Two years later, lured by the image of a nation fighting for liberty, he bought a ship at the age of 19 and sailed to America to volunteer in General George Washington’s army.

He explained his attraction to the revolutionary cause in a letter to his wife: “The welfare of America is intimately connected with the happiness of all mankind; she will become the respectable and safe asylum of virtue, integrity, tolerance, equality, and a peaceful liberty.”

He first saw action at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777 where he was shot in the leg and spent two months recovering from his wound at the Moravian Settlement in Bethlehem.

His heroism in the battle encouraged George Washington to give the young Frenchman command of a division and Lafayette stayed with his troops at Valley Forge. After a brief visit to France in 1779, he returned to the Revolution in 1780 aboard the Hermione and helped contain British troops at Yorktown in the last major battle of the war.

His heroism in the battle encouraged George Washington to give the young Frenchman command of a division and Lafayette stayed with his troops at Valley Forge. After a brief visit to France in 1779, he returned to the Revolution in 1780 aboard the Hermione and helped contain British troops at Yorktown in the last major battle of the war.

As principal author of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” (1789), written in conjunction with Thomas Jefferson, he helped propel the French Revolution. As an ardent supporter of emancipation and a member of anti-slavery societies in France and America, Lafayette lobbied for the restoration of civil rights to French Protestants and he was instrumental in ensuring that religious freedom be granted to Protestants, Jews, and other non-Catholics.

He was known as a friend to Native Americans and he endorsed the views of leading women writers and reformers of his day.

His triumphal Farewell Tour of America in 1824 during the new nation’s 50th anniversary proved the Marquis had lost none of his rock star status. His arrival in New York prompted four days and nights of continuous celebration – a response replicated during his visit to each of the then-24 states of the Union. When Lafayette visited Congress, Speaker of the House Henry Clay delivered an address citing the deep respect and admiration held for him due to his “consistency of character . . . ever true to your old principles, firm and erect, cheering and animating, with your well-known voice, the votaries of liberty, its faithful and fearless champion, ready to shed the last drop of blood, which here, you so freely and nobly spilt in the same holy cause.”

His triumphal Farewell Tour of America in 1824 during the new nation’s 50th anniversary proved the Marquis had lost none of his rock star status. His arrival in New York prompted four days and nights of continuous celebration – a response replicated during his visit to each of the then-24 states of the Union. When Lafayette visited Congress, Speaker of the House Henry Clay delivered an address citing the deep respect and admiration held for him due to his “consistency of character . . . ever true to your old principles, firm and erect, cheering and animating, with your well-known voice, the votaries of liberty, its faithful and fearless champion, ready to shed the last drop of blood, which here, you so freely and nobly spilt in the same holy cause.”

Easton lawyer James Madison Porter was so impressed upon meeting the Marquis in Philadelphia that year that he proposed naming the town’s new college after Lafayette as “a testimony of respect for his talents, virtues, and signal services . . . in the great cause of freedom.”

On June 30, 1832, a month after the first students matriculated at Lafayette College, five of them—members of the Franklin Literary Society—wrote to Lafayette that they had made him an honorary member to pay “a feeble though sincere tribute of regard to a man who has proved his own and our country’s benefactor, and whose enlarged philanthropy as with a mantle of blessedness would cover the whole family of man.”

On August 7, 2002, 178 years later, Congress made him an honorary citizen of the United States and in May 2010 the only college in America to bear his name awarded the Marquis the honorary degree of Doctor of Public Service (posthumous) at its 175th Commencement.