Alcohol. Is it a harmless addition to the agenda of a college campus party or a major cause of death among adolescents in the U.S. and throughout the world? Unfortunately, and perhaps unsurprisingly, multiple viewpoints suggest that the latter is the case. Specifically, the problem of drunk driving is by far the leading issue of underage drinking, attempted to be solved by the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) laws. For decades, there has been a heated debate over the effectiveness of the MLDA in solving the matter. Many scientists, research institutes, and governmental organizations insist in favor of the restrictions, with abundant data to support their claims. Perhaps a matching party of advocates argues the opposite, claiming that MLDA laws are ineffective, or even exacerbate the problem altogether. In this essay, I will argue to uphold the minimum legal drinking age laws by looking at the issue from three key perspectives: research data of fatal drunk driving accidents among adolescents in the U.S. and Lithuania; historical evidence comparing the status quo before and after the enactment of the Uniform Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984; and data from the medical point of view suggesting that exposure to alcohol at a young age considerably increases the risk of drunk driving in the adulthood. I will also present some common counterarguments, such as the general insufficiency of the law’s impact, that are used by the adversaries of MLDA, and provide the rebuttal of these claims.

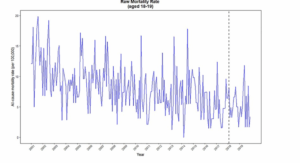

Perhaps the most convincing way to look at the impact of the MLDA law is by examining the factual reduction in the number of drunk driving accidents after the law’s enactment. Lithuania is an excellent example, as it adopted the minimum drinking age of 20 years on January 1, 2018. A recent study has concluded that there was “a notable decline in all-cause mortality rates among young adults in Lithuania” after the enactment of the MLDA law (Tran et al., 2022). The study has analyzed the mortality rates in three age groups, the target group of 18–19-year-olds and two control groups of 15-17- and 20–22-year-olds, since they were unaffected by the policy. As expected, results have “[…] demonstrated that there was a decrease in mortality following the MLDA policy” in the target group. Specifically, after 2018 there was a decrease of 3.07 deaths per 100,000 per year for those 18-19 years old, as opposed to the decrease of 0.08 deaths between 2014 and 2019. These findings support the claim that alcohol was responsible for a significant number of deaths among adolescents and that the enactment of the MLDA laws has decreased this mortality rate. Figure 1 shows this decrease, and the date of law enforcement is indicated with a dashed line.

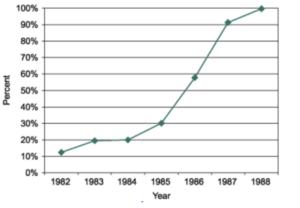

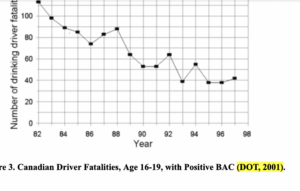

In addition to the data gathered recently, it is important to look at the dynamics of the drunk driving death rate before and after 1984, when the Uniform Minimum Drinking Age Act was passed. Before this year, states determined age limits themselves, ranging from 18 to 21. During the Vietnam War and the “old enough to serve, but not be served” movement, most states lowered the drinking age to 18. This had chilling consequences. The surgeon general of the U.S. had reported in the early 1980s that “[…] longevity was increasing for all age groups except one — those under 21 — and the leading cause of their deaths was drunk driving” (Scrivo, 1998). When individual states increased the legal drinking age, adolescents would travel to a bordering state with a lower drinking age limit to consume alcohol. They would then try to make it home, which led to many fatal car accidents in the 1970s. This called for a uniform drinking age restriction that was later enacted. Figure 2 shows the rate at which each state imposed the Uniform Minimum Drinking Age. Since then, roughly 1,000 families are saved every year, amounting to 38,000 lives to date. Convincing evidence is provided by the U.S. Department of Transportation (2001), showing a sharp decline in driver fatalities of individuals aged 16-19 with positive blood alcohol content (BAC). Interestingly, Canada has also experienced a similar trend during the same time, as illustrated in Figure 3. From 1982 to 1997, the number of drinking driver fatalities in Canada decreased by almost two thirds: from 112 to 41. This shows that MLDA is necessary, since drunk driving was a severe problem before the law, and the nature of the problem required a uniform restriction across all states.

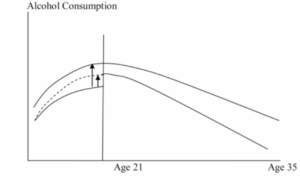

The last, and perhaps the most consequential factor bolstering the argument for MLDA, is the effects that early alcohol exposure has on adolescents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) have shown that “[…] after all states adopted an age 21 MLDA, drinking during the previous month among persons aged 18 to 20 years declined from 59% in 1985 to 40% in 1991.” Surprisingly, individuals aged 21 to 25 also saw a decrease in alcohol consumption, “[…]from 70% in 1985 to 56% in 1991.” Additionally, CDC claims that 21 MLDA protects drinkers from developing alcohol and other drug addiction, adverse birth outcomes, and suicide and homicide. Another piece of evidence comes after further analyzing traffic fatalities. Kaestner and Yarnoff (2011), have concluded in their study that “[…] the difference between an environment in whicAh a person was never allowed to drink legally at those ages and one in which a person could always drink legally is associated with a 20-33 percent increase in alcohol consumption and a 10 percent increase in fatal accidents […]”. Figure 3 shows how the difference in alcohol consumption associated with different MLDAs gets exacerbated as people age. This shows that the higher legal drinking age reduces the chance of fatal driving accidents by lowering the risk that an individual will develop alcohol dependence, consume it more frequently, and therefore engage in drunk driving.

As mentioned in the introduction to this essay, there is an active advocacy for lowering the minimum legal drinking age to 18 or 19, as it is in most European countries. Most vivid counterpoints focus on the significance of the decrease in drunk driving incidents, on possibility of a presence of a confounding variable to skew the statistics, and on the sufficiency of drop rates of alcohol consumption. I will provide reasoning and evidence to undermine these claims.

One of the most common arguments is that even though alcohol-related traffic incidents have decreased, the extent of the decrease was not as great as anticipated (Hanchey, 2009). I would like to respond that while it is true that the number of underage alcohol-related accidents did not drop to 0 immediately after the enactment of the law, the decrease in the first decade was big enough to be considered statistically significant. As Hurley describes, roughly 1,000 lives are saved every year due to the MLDA law, so the results are indeed significant enough to call this law successful (Scrivo, 1998). Hanchey also claims that because there was a decrease in traffic accidents for persons aged 21 to 25, there must be a confounding variable that contributed to the statistic. Perhaps this is true. However, Kaestner’s research shows that the decrease for young adults was still considerably greater than that for the adult population, and it would be unjust to say that the legal drinking age had no impact (Kaestner et al., 2022).

Another major claim to discredit MLDA is that the rate at which the consumption of alcohol has been dropping is not sufficient (Hanchey, 2009). I believe that this argument focuses on the outcome of the current status quo and fails to recognize the consequences of changing it. First, as already mentioned, it is impossible to decrease underage consumption to 0, especially since many young people get alcohol from their families in a controlled and safe environment. Second, considering the argument made by Hurley, it is very likely that after lowering the legal drinking age we will face the same consequences as were seen during the Vietnam War: a sharp increase in the number of drunk driving accidents, fatalities, and a decrease in the lifespan of young adults (Scrivo, 1988).

In conclusion, there is extensive and far-reaching evidence suggesting that MLDA has been a very important tool for fighting underage drunk driving. Empirical evidence suggests that countries that impose stricter MLDAs see a decrease in alcohol-related car accidents. This was evident when analyzing Lithuania. History also holds many answers, and this essay discussed the context under which the MLDA was increased, the Vietnam War, and a sharp decrease in both alcohol consumption and fatal drunk driving accidents. The last point was the research showing that early exposure to alcoholic beverages leads to addiction and that effects get exacerbated with age. This not only leads to an increased risk to the individual’s health but also raises the chance of engaging in drunk driving. I concluded by listing some counterarguments and providing rebuttals with reasoning. When it comes to legislation, the protection of the freedoms of the citizens is always a priority. However, the importance of children’s safety and well-being is hard to overestimate.

References

Age 21 minimum legal drinking age (2022, April 19). CDC. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/minimum-legal-drinking-age.htm

Hanchey, C. (2009). The Failure of Drinking Age Laws. Lafayette Library. https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=02f13757-e903-461c-8309-6982be560110%40redis

Kaestner, R., & Yarnoff, B. (2011). Long-Term Effects of Minimum Legal Drinking Age Laws on Adult Alcohol Use and Driving Fatalities. The Journal of Law & Economics, 54(2), 325–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/658486

Scrivo, K. (1998, March 20). Drinking on campus. CQ Researcher, 8(11), 241-264. http://library.cqpress.com/

Tran, A., Jiang, H., Lange, S., Livingston, M., Manthey, J., Neufeld, M., … & Rehm, J. (2022). The Impact of Increasing the Minimum Legal Drinking Age from 18 to 20 Years in Lithuania on All-Cause Mortality in Young Adults—An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis. Alcohol and alcoholism, 57(4), 513-519.

What caused the disease? (2001, September). Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://one.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/research/feweryoungdrivers/iv__what_caused.htm