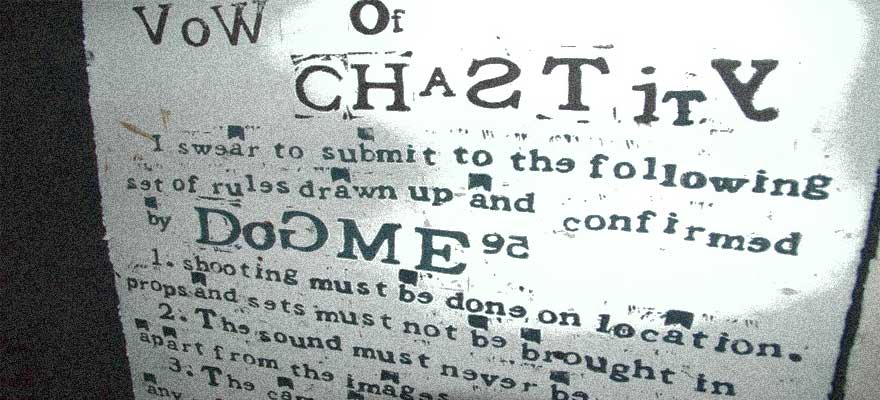

This film was very intense, I had no idea what to expect when watching it. It was in another language, about a family reunion, and seemed like the perfect set up for a murder mystery film. And them that huge bomb dropped at dinner, that Christian’s father had raped, molested, and sexually abused him and his twin sister when they were young. I remember looking around class during this part of the film and seeing other people doing the same thing in shock and amazement. That changed the whole film from then on out, and everything was much more dark, whereas before it almost passed as a light-hearted comedy. Kinda like that family reunion no one wants to go to. I love my family, but I wouldn’t enjoy having one of them singing a long, sad song while I’m waiting for my food. I liked the film a lot and I noticed that it was made in the Vow of Chastity manner of Dogme 95.

I could not disagree more with the “Vow of Chastity” and it’s rules. In the reading they say “film is dead, and needs Resurrection.” I can’t think of a faster way to kill off an entire art form than to make all films in that manner. This particular film was not boring and was made this way, but calling for all films to be this way is absolutely absurd, for many reasons. For one thing, it is possible to make something that is realistic without those rules, just because you have lighting and sound added in does not make the film less real, if anything it can make it more real by taking away from poor audio and poor video quality. Secondly, people do not go to the movies to see things that are pure reality and have nothing new to offer them. Film is an escape, and making films in this manner I personally think would get, well, boring. I’m not saying all films should be made by Michael Bay (poor guy gets so much crap, but he makes movies for teenagers, whatever) but there is nothing wrong with adding effects to achieve realism, or to add to a film. With this rule thousands of the best films ever made would not have been “allowed,” I know they were not calling for a total overhaul of film, but I think there rules were too strict. Very often it is the unreal that makes a film better (the CGI in Jurassic Park looks real, and is the main reason people went to see that movie… and the soundtrack to many films are there best qualities.)

Nick Tassoni