Within the political analysis of this report, we will discuss environmental policy and how it has intersected with Easton’s political climate. Then, to provide a basis for the implementation of green roof policy specifically in Easton, we will evaluate different green roof associations, guidelines, and policies abroad for their effectiveness and alignment with Easton’s environmental goals. Finally, we will discuss the differences between public and private investments for green roofs in Easton and how Easton’s government can take action toward implementing green roof policy. There are also several political characteristics specific to Easton which could hinder green roof installation. This includes maximum building heights specified in zoning codes and requirements in the historic district mandating any new building or addition be passed by a committee.

Environmental Policy:

Environmental policy is crucial to sustainability management. However, producing effective and efficient policies regulating environmental issues is complicated because environmental issues are inherently interdisciplinary, and are defined inconsistently in different disciplines. Due to the malleable definition of environmentalism, environmental policies are also easily manipulated to serve an agenda. This manipulation is observed within the struggle between the general public and private organizations regarding environmental issues. While large organizations attempt to contain the scope of issues and resolve them privately, individuals work to broaden issues and bring them further into the public agenda. However, because large organizations often carry more political weight than the individual, they are able to frame a public concern as a non-issue to avoid addressing it (Cohen, 2006).

Another problematic quality of environmental policy is its innately quantitative nature. It is invaluable for environmental policymakers to consider the qualitative benefits the public experiences from the environment which evade quantification (Cohen, 2006). Lacking consideration for these qualitative environmental benefits is a common theme within environmental policy which often results in unforeseen social, political and economic consequences. Within Easton, if policymakers do pursue environmental policy regarding green roofs, it is important that they evaluate policies for their non-political and non-technical implications. To do this most effectively, policymakers should use ample input from community members in defining the environmental issues which policies aim to address. This community-centric method of defining environmental issues is the most promising method of mitigating unforeseen consequences due to environmental policy.

In Easton, there are several environmental issues at the forefront of the public agenda. In the Easton Matters Report, residents and city officials identified flooding, water quality, air quality, access to food, crime and drugs, and trash and litter as their key environmental concerns, varying by neighborhood. While conducting research, the Nurture Nature Center also observed that residents of Easton care more about neighborhood pride and cohesion than is currently represented in city-wide planning. Although the Nurture Nature Center’s report provides a general sense of individual neighborhoods’ key concerns, more extensive research of individual neighborhoods is necessary before taking tangible steps toward defining environmental issues in a way which best represents the community’s needs (Frankel & Goldman, 2017). However, given this preliminary research, we predict that the installation of green roofs throughout several neighborhoods in Easton may effectively address community-identified environmental concerns.

Public and Private Buildings:

Green roofs can be installed on a diverse set of buildings, generally depending on specifications such as roof slope, maximum dead load, and maximum height. Although they can be installed on both public and private buildings, the political implications of each vary due to the proportion of public and private benefits experienced. Green roofs require a large upfront investment, while many of their benefits are granted externally to the public, such as air and water quality and stormwater management. This means that incentivizing green roof installation on public buildings depends mainly on the alignment of green roof benefits with community-defined environmental concerns and the liquidity of public funds. However, private green roof investors experience only some of the benefits due to green roofs, including lowered energy costs and extended roof life which are long-term benefits. Because the tangible benefits produced by green roofs are not experienced immediately by private investors, incentivization through policy would be necessary to encourage private investment in green roofs. The difference in economic benefits granted to the public and privately is addressed further in the economic section, located here.

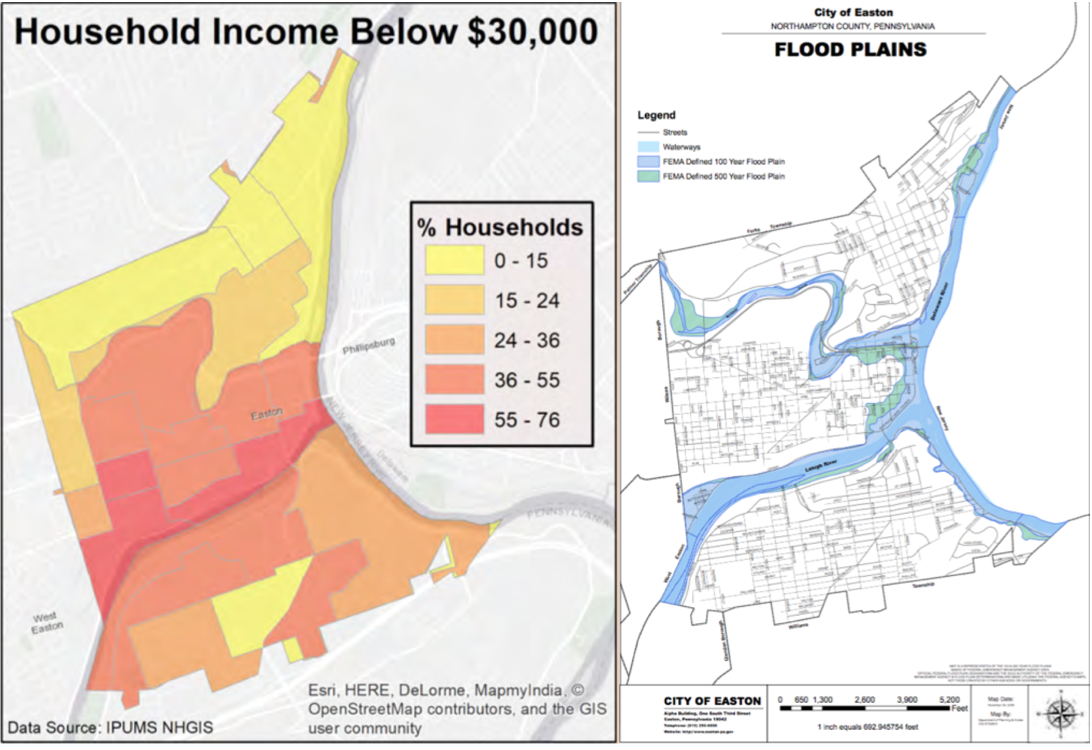

To determine whether a policy should be implemented in Easton to encourage private investment in green roofs, it is important to consider the equity of installing green roofs on only public buildings. Most of the public buildings in Easton are located downtown, meaning that if green roofs were only installed on public buildings, the West Ward, South Side, and College Hill would not experience their benefits. Additionally, the overlap of floodplains and average household income below $30,000, demonstrated by Figure 11 and Figure 12 below, indicate that residential areas without the economic means to make a large investment are the areas which would benefit the most from a green roof system. This indicates that policy to economically incentivize individuals and organizations to install green roofs across Easton may be the best way to attain equity while still reaping the benefits from a green roof system.

Figures 11 and 12:

Figure 11. A map of the distribution of households with annual income below $30,000 in Easton, Pennsylvania. Adapted from The Easton Matters: Evaluation Report by the Nurture Nature Center for the City of Easton, 2018.

Figure 12. A map of the floodplains in the city of Easton, Pennsylvania. Adapted from The Easton Matters Report by Nurture Nature Center for the City of Easton, 2018.

Existing Green Roof Policy:

We intend to explore the feasibility of implementing policy regulating green roofs in Easton by assessing different types of green roof policies which have been implemented in other communities. These policies will be evaluated based on the environmental issues they aim to address if those issues align with Easton’s as defined by the Easton Matters Report (Frankel & Goldman, 2017), and for their effectiveness in addressing those issues. Several countries with more extensive environmental policy than the United States have developed somewhat robust green roof initiatives. One common theme among these countries is the establishment of nation-wide guidelines and associations dedicated to green roof standards which protect users and investors from receiving sub-standard green roof systems (Ismail et al 2012). Figure 13 below highlights several other countries which have developed national green roof associations and guidelines, as well as a brief summary of the content of their guidelines. If Easton were to implement city-wide guidelines, it would likely benefit policy-makers to review these guidelines more closely and model Easton’s guidelines after those in countries with similar environmental issues.

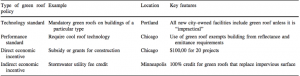

Figure 13. A list of countries with developed national green roof associations and guidelines, as well as a brief summary of the guidelines. Adapted from Establishing Green Roof Infrastructure Through Environmental Policy Instruments, T. Carter & L. Fowler, 2008.

In Japan, The Organization for Landscape and Urban Green Technology Development promotes urban greenery and green spaces with the main goal of mitigating the urban heat island effect. Although Easton does experience an urban heat island downtown, it has not been identified as a key concern by Easton’s policymakers and residents. Therefore, although Japan has experienced benefits from promoting all buildings to have small green roofs because Easton’s concerns are more water-related, this would likely not be a beneficial system for Easton to emulate. In Canada, however, the first green roof regulation was adopted in 2006 by Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, which required buildings of over 5000 square meters to have green roofs. The main purpose of this regulation is to decrease energy consumption, increase stormwater control, and increase thermal performance. Other benefits obtained were enhanced aesthetic views and biodiversity. These benefits align well with Easton’s needs and were successful in Canada, but a standalone policy will not encourage enough investment in green roofs to develop a beneficial green roof infrastructure. In order to reap the intended environmental benefits from green roofs, the public must have a cohesive environmental agenda, as is pursued within green roof associations and guidelines in other countries (Ismail et al, 2012).

Beyond the development of nation-wide green roof associations and standards, four general types of policy which can be enacted at the state-wide and municipality-wide level to encourage the installation of green roofs are briefly explained Figure 14, below. There are two types of standard-based policies, which require certain buildings to adhere to a specified standard. A technology standard requires certain types of buildings to have a green roof proportional to the size of the building. A performance standard requires a certain level of sustainability for all buildings of a certain type; a common example of this is a required level of stormwater management. There are also direct and indirect economic incentive policies. Examples of direct economic incentives are grants and subsidies, which are credited to a green roof investor to aid in the costs of installation and maintenance. An indirect economic incentive policy is when money is credited back to a building owner for installing a green roof, such as in tax breaks and stormwater fee credits (Carter & Fowler, 2008).

Figure 14. Four general policy types which could be used to encourage green roof implementation, as well as a short explanation and example of each. Adapted from Establishing Green Roof Infrastructure Through Environmental Policy Instruments, T. Carter & L. Fowler, 2008.

Technology Standard Policy:

A technology standard policy regarding green roofs would mandate in the building code of a jurisdiction that all buildings of a specific type must green all or part of their roof. For example, in Linz, Austria, all new buildings larger than 100 square meters with a slope lower than 20% are required to have green roofs. In the United States, Portland, Oregon has enacted a technology standard policy which requires all new city-owned facilities to include a green roof with at least 70% coverage, unless it is deemed impractical. This policy, specifically, is detrimentally vague, as the term ‘impractical’ is not defined within the guideline and can, therefore, be redefined by a building owner attempting to avoid green roof investment. A technology standard policy may be beneficial to a city attempting to implement city-wide green roofs and reap the maximum benefits possible from a robust green roof infrastructure. However, technology standard policies have an innate fault, as they assume that an entire jurisdiction will benefit from green roofs equally. This ignores other potential environmental solutions and can lead to a lower community benefit than is anticipated by policymakers. Specifically, in Easton, because different neighborhoods identified different key environmental concerns, a technology standard policy highlighting green roofs as the only environmental solution may not be ideal (Carter & Fowler, 2008).

Performance Standard Policy:

Performance standard policies identify sections of cities or areas of new development to be held to tighter environmental controls. These policies often define environmental goals regarding stormwater management, urban greening, or the urban heat island effect, and require new buildings and developments to adhere to them. For example, in Berlin Germany, an inner-city area was redeveloped after decades of dilapidation, and a mandate was passed during its construction requiring the project to maintain 99% of its stormwater on-site. This was achieved using several stormwater management tactics, including the installation of several extensive green roofs. In the United States, several states, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and North Carolina have adopted manuals which define stormwater management standards and identify green roofs as a stormwater best management practice (BMP) which can be used to meet these standards. Performance standard policies such as these identify cohesive environmental issues which a jurisdiction aims to address while leaving the manner of addressing those issues up to the individual owner or investor (Carter & Fowler, 2008).

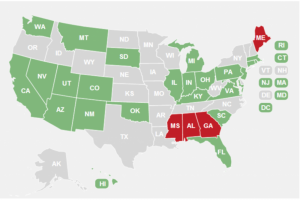

Another example of a performance standard regulation is Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). LEED is a rating system created by the United States Green Building Council (USGBC) that certifies buildings with a classification based on their level of environmental performance or sustainability. Many cities are beginning to require newly constructed buildings to achieve a certain level of LEED classification in order to be erected. Notably, Washington D.C. has stringent LEED requirements for newly constructed buildings and is also the jurisdiction with the largest abundance of green roofs in the country (Cities Requiring or Supporting LEED, 2018). Additionally, although Pennsylvania has not enacted state-wide LEED requirements, both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia have enacted city-wide requirements. A full list of jurisdictions with LEED requirements can be accessed here, and a map of states with city-wide LEED requirements can be found in Figure 15 below. If a state is green, it means that there is some form of LEED certification required within that state. If a state is red, it means that they have some form of anti-LEED legislation, likely because they view the LEED certification system as flawed and believe another system should be used to assess sustainability. If a state is grey, it means that they do not currently have any form of legislation regarding LEED certification.

Figure 15. A map highlighting states which have a jurisdictional policy in place that requires new buildings to be LEED certified. Adapted from Cities Requiring or Supporting LEED, everblue Training, 2018.

Buildings receive points based on a set of categories established by the USGBC; to receive general LEED certification, a building must receive a score of 40 or more points, a silver certification requires 50 points, gold requires 60, and a platinum certification requires 80 points. The addition of a green roof can earn a building up to 15 points, depending on how effectively the green roof is integrated with the building’s other systems. A more extensive breakdown of how points can be achieved can be found here.

Direct Economic Incentive:

Direct economic incentives to encourage green roof installation are realized in the form of subsidies and grants. Green roof projects can qualify for subsidies by meeting certain requirements such as stormwater retention or vegetation coverage. Two forms of subsidies that could encourage private investment in green roofs are general subsidies and targeted subsidies. General subsidies give money back to a building owner who adopts a green roof, proportional to the size of the green roof. A targeted subsidy is different, in that the building owner only receives the subsidy if the net private benefits of adoption are negative. This policy ensures that the green roofs are in fact benefiting the community (Mullen, Lamsal, & Colson, 2013). In Germany, approximately 50% of cities offer direct subsidies to building owners installing green roof systems which cover from 10% to 50% of installation costs. In North America, subsidies and grants are used sparingly to encourage green roof implementation. There are currently no jurisdictional programs within the United States which offer grants proportional to unit costs of green roofs. Instead, there are few highly competitive lump-sum grants available. With this in mind, it may be difficult to employ a policy within Easton which provides direct economic incentives for installing green roofs (Carter & Fowler, 2008).

Indirect Economic Incentive:

The most common type of green roof installation incentive is an indirect economic incentive policy. This type of policy provides indirect financial incentives to building owners who achieve a certain standard of sustainability or environmentalism. A common example of this is a stormwater utility fee credit, which involves a building owner receiving a reduction in their annual stormwater utility fee proportional to the amount of stormwater they manage on-site (Carter & Fowler, 2008). Another example of this type of policy is a tax break for building-owners who implement green roofs (Shiah, 2011). In 2007, to minimize upfront costs, Philadelphia began to offer 25% tax rebates of all costs incurred by green roof installation, up to a value of $100,000. In 2008, New York City began to offer buildings that cost over $2,000,000 a tax credit of $4.50 per square foot if they construct a green roof. Policies in New York and Philadelphia cover approximately 1/4 of the fixed green roof costs while policy in Washington D.C. covers a majority of the costs (Wells, 2016). Although this type of policy is the most common in green roof incentivization, it is best suited for large corporations with the economic resources to realize the installation costs of green roofs and make a long investment in them. In Easton, because the areas which experience the most severe environmental issues such as flooding also often have lower average household incomes, this type of policy would likely not be the most beneficial for Easton’s residents.

Easton’s Government:

To understand how a policy regarding green roofs can be passed in Easton, it is important to understand the way Easton’s government works. Although Easton is a part of Northampton County, it regulates its own municipal government through enacting ordinances. The law that allows Pennsylvania municipalities to adopt these ordinances was created by the Pennsylvania General Assembly in 1933 through Act 69, Article XVI. This act ruled that the board of supervisors for a township can adopt ordinances which they then defined as “a piece of legislation enacted by a municipal authority”. Easton’s citizens vote every four years on the officials that will represent them as a member of this council (City of Easton, 2009).

In general, the process of implementing an ordinance is simple, although it can differ between municipalities. Easton’s council meets every other Wednesday at the Easton City Hall at 6 pm and is open to the public. Additionally, a private meeting is held the Tuesday before these Wednesday meetings for just council members. The meeting minutes are typically posted publicly on the town website to encourage transparency and community engagement in local issues (City of Easton, 2009).

The process of bringing a potential ordinance into fruition is a community effort and grassroots movement by individuals looking to make a change. An ordinance starts as a proposal, created by any resident(s) of the city, who have identified a local issue and wish to propose a solution. This proposal could come from a multitude of sources, such as local politicians, private citizens (through public forums or petitions), as well as the council, board, or committee meetings. Upon receiving the proposal, the city council discusses and evaluates the proposal. The council also has the ability to create a specialized committee to research, report, and make recommendations based on their findings. The proposed ordinance is read every time it is proposed to the city council, and the council is required to hold at least one public hearing. This gives the public a formal opportunity to provide input on the idea. Following all public hearings and their final discussions, the city council votes on the ordinance. Depending on the legislature, the mayor may have the final say on whether it is passed. If it is passed, however, the ordinance is official and takes effect based on the agreed upon enactment process (City of Easton, 2009).

Conclusion:

The composition of Easton’s government allows a green roof policy to reasonably be passed. For this to happen, the town’s citizens and council members would need to decide for themselves whether green roofs should be implemented. Our project avoids suggesting that we know what is best for another community and instead lets the community decide if they would like to pursue green roofs based on our framework. The resources and time that go into adding green roofs could theoretically be expended towards other issues defined by Easton citizens, such as a new school or a food shelter. Bringing the idea to elected officials encourages them to make the best political decision for their residents.

It is up to the council to decide if a public work is fit for implementation based off of the evidence and framework presented. This council is a strong forum to gain public backing and is the likely channel for a green roof policy to be implemented. Through the ordinance system, and within a local municipality such as Easton, adding green roofs could reasonably become a reality. This policy would be driven by the city council, implemented through public works, and work toward benefitting Easton as a whole. However, before a policy can be used to implement green roofs, the technical aspects of the green roof itself and its intended building must be evaluated.

To read the Technical Context section of our report, click here.