Technical Context

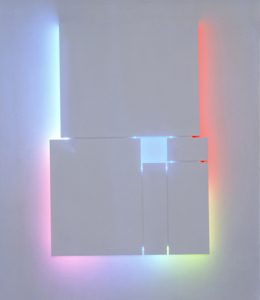

Another possible option our team investigated for the eastern wall of Acopian Engineering Center is a vertical art installation utilizing light, contrast, and shadows. In an interview, Professor Kerns directed our focus to a number of new pathways, one of which was towards the artist Stephen Antonakos. Renowned for his artwork utilizing neon light and rectangular panels to create visually stunning contrasts of color and shadow (“Stephen Antonakos,” n.d.).

Lafayette College and the greater Easton area is no stranger to Stephen Antonakos’ artwork. In 2011, Antonakos was a part of a press conference at the Simon Silk Mill. As a part of their redevelopment plans, the Redevelopment Authority of Easton brought in Antonakos to create a piece for the Simon Silk Mill. At the conference, they revealed the concept of his work: A light design mounted on the one-hundred-foot tall smokestack on site at the silk mill, acting almost as a beacon for people traveling the Sterner Arts Trail (“Artist Wants to Light Up the Silk Mill,” 2011). This is not the only piece of his near Lafayette. Inside Buck Hall’s lobby, there is a second piece by the artist titled “For JT,” shown below:

Figure 17: Antonakos’ “For JT”, (“Stephen Antonakas,” 2018)

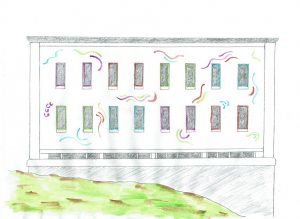

Figure 18: Concept for Silk Mill (“Artist Wants to Light Up the Silk Mill,” 2011)

We do not have access to exact specifications of Acopian Engineering center, but for the purposes of estimating material needs at this time, we can compare the relative size of nearby objects as compared to the building. For example, using the most recent Google Maps data via satellite imaging, we see two bicycles parked in front of the building. Using the relative size of one bicycle to the building, we can relate a number of bicycle lengths as a unit of measure for the building. The average size of an adult bicycle is around sixty-eight inches, and we can use this as our approximate conversion (“Bicycle Parking Info,” n.d.).

Using this method, we see the brick section of the east wall of Acopian Engineering Center is roughly 60’ by 20’ (59’ 5 4/24” x 19’ 9 ¾”). Additionally, window sizes are roughly 3’ 9” by 5’ 7” (3’ 8 21/25” x 5’ 6 3/5”). This gives us an idea of how much neon lighting and other materials will be needed. From here, we have options. Either the installation can be neon lighting with no other components as tubing on the outer wall or as tubing lining the windows, as seen in the public work “The Search.” Another option could be similar in style to Antonakos’ piece “Respite”. Both pieces are shown below.

Figure 19: “Respite” (Stephen Antonakos, 2018).

Figure 20: “The Search” (Stephen Antonakos, 2018).

The primary and most important part of the lighting installation will be the neon tubes. It is possible to purchase them in their glass tube form or as bendable tubes which can be cut and altered to length and position. Multiple online distributors sell the neon tubes as well as accessories. Accessories include brackets for mounting, plugs, covers and connectors. Were we to go with lighting only along the perimeter of the windows on the building’s east side, we would need roughly 18’ 8” per window, or a total of about 300’ for the sixteen windows on that wall.

If we were to go with panels in front of the lighting elements, we would need wood or plastics capable of withstanding outdoor elements and would need to determine the shapes or objects they would represent. If the desired shapes are not rectangular, we would need to take into account material sizes required to cut the desired formed. Finally, there is the thought of hardware and bracketing for attaching the panels to the face of the wall, as well as equipment or scaffolding to get people to the necessary height to hang and mount pieces.

Figure 21: Final light art concept design as created by Olivia Guarna (2018)

Economic Context

The main component for this version of our proposed art installation is the neon light fixtures. Spools of 150 feet are available online for $700 to upwards of $760, depending on color (“21 results for ‘neon’ | 1000Bulbs.com,” 2018). The light spools can be cut at eighteen-inch intervals and are rated for outside usage. The lights are expected to operate through 30,000 life hours and have the added benefit of operation through singular or multiple LED failure. As the installation is on the exterior of the building, the lights will only operate from dusk to daylight, when the art will be most visible to the public. This reduces maintenance and replacement cost significantly, as instead of twenty four hour operation, power will be supplied for between twelve to fifteen hours, depending on season and sunlight fluctuation day-to-day.

The lights require power supplies and brackets to connect to the wall. Individual power supplies run for about $145 and transformers run for around $100. Bracketing, connectors, and other accessories run at much lower prices, ranging from packages of ten end caps for $1.38 to $7.25 for mounting clips and $12.29 for splicing cables and pins. Mounting clips come with the necessary screws for connection onto a surface. If we were to apply only neon tubing to the sixteen windows, which we know from before requires roughly 300 ft of tubing, then the cost of lights is upwards of $1500, not including necessary brackets and power supplies. Brackets, assuming four per window, wind up at about $29 and power supplies, because it would be sixteen separate installations (unless we linked them behind the brick with extenders) would be upwards of $1600.

If, instead, we go with backlit panels where the art is a mixture of the bleeding light and shadows from covered space, the light pricing changes drastically, but this is dependent on desired shapes. Antonakos’ covered lighting style often used rectangles of painted wood, but he occasionally used curved or three-dimensional pieces. We are confined in design by the placement of the windows, not by the shapes we would desire. These panels and shapes would be made from a pressure treated/weather resistant wood. A 2’x4’x1/2” sheet of pressure treated exterior plywood costs $17.98 per sheet (Lowes.com, 2018). Not including bracketing/attachment, the cost of wood could increase rapidly.

The benefits of using light elements for an art installation are the very low maintenance costs as well as the long lifespan. To get the full effect, operation should be conducted only in the dark or dim light. As such, the effective life of the lights will be longer due to lessened use per day. Upkeep of panels, if used, will cost a little more, but should last for quite some time, and can be easily replaced if damaged.

In addition to the costs laid out above, though, there is a larger economic context to consider here as well. This design is heavily influenced by the work of Stephen Antonakos. It also draws from aspects of Professor Kerns’ studio practice that he shared with us. This piece even more so than the mural is a true installation piece. For that reason, the school would likely need to go through the process of commissioning an artist to complete the project. For civic projects, this can be involved and demand some time and resources. The Los Angeles County Arts Commission outlines their civic art procedures for a 2016 project. Their artist selection process included the following four steps: artist selection panels, selection of project artist(s), establishment of pre-qualified list, and conflict of interests. They fill their panels with individuals who have “background or professional expertise in the arts,” (Los Angeles County Arts Commission, 2016, p. 4). We might like to broaden this definition based on the way we have structured our entire design process; we would consider including other stakeholders in the panel in addition to artists. The establishment of a pre-qualified list of artists is also a key step. Having a strong understanding of our influential artists in the project (such as Stephen Antonakos) will narrow our search significantly and direct us more quickly towards appropriate options. Further, we can search within our own community for qualified parties. In fact, Professor Kerns suggested that this project might be accomplished in house.

Next steps include sending out Requests for Qualifications (RFQ) and Requests for Proposals (RFP) (Los Angeles County Arts Commission, 2016, p. 7). Once a proposal is chosen, contract negotiations must take place with the artist. Further, with this type of project, a maintenance and conservation plan must be made in consultation with the artist. All this must take place before the implementation phase. This process is not unique to this alternative. However, if we strive to create a more complex installation here, it will demand the necessary time and resources to move through this procedure.

To read about our third design alternative, click here.