Cost (Con)

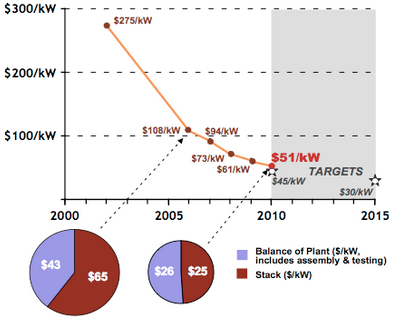

The price for these vehicles is simply not comparable to conventional or even hybrid vehicles. Toyota’s most recent price point for their fuel cell car, the FCV, is $50,000. In a 2008 study, the NAS estimated the average cost of an FCV from 2008 to 2023 at $39,000 per vehicle, including research, development, and deployment (RD&D) costs. A study by MIT that examined energy and environmental impacts of fuel and vehicle technologies for light-duty vehicles indicated the costs would decrease over the long-term. The study estimates that a fuel cell car in 2035 will cost $5,300 more than its gasoline counterpart, which would have a retail price of $21,600 (in 2007$). (“Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles”, The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions)

Lack of Infrastructure (con)

Chicken and egg problem. Why would people want to buy this vehicle if there are no fueling stations near them? Infrastructure development takes initial investment from either private entities or the federal government, and thus far, no real strides toward broad implementation have been made despite the fact that the government has been funding research and development of this technology for more than 20 years.

Range Limitation (con)

Range is limited by tanks, storing enough hydrogen to obtain a vehicle range of 300 miles would require a tank too large for a typical car. Currently the most cost-effective option is using high-pressure tanks, yet these systems are large, heavy, and too costly to make FCVs cost-competitive. Other options include storing hydrogen in metal- or chemical-hydrides or producing hydrogen onboard, which are still in R&D stages. (“Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles”, The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions)

Combustible gas (con)

Hydrogen has a low burning temp, so chances of secondary fires are very low, but improved casing for the hydrogen tanks on board is a must. In addition, the fact that these tanks explode (even though they do not burn hot enough to do much harm) makes this technology hard for society to swallow. Yet another roadblock.

GHG effect (Pro)

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles emit no greenhouse gases from vehicle operation. The only emissions from these cars’ life cycle analysis (LCA) come from the fuel production and physical vehicle production. The following image depicts the basic steps of the fuel cycle and vehicle cycle of building a car when greenhouse gases might be emitted.

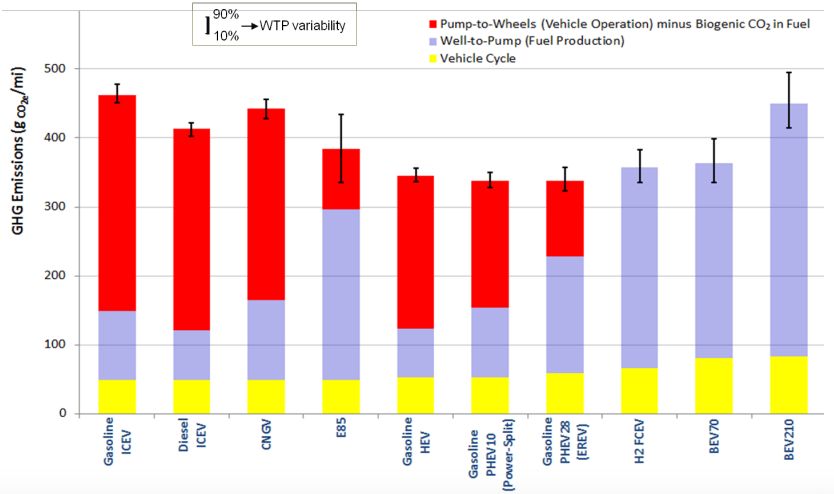

Comparing hydrogen fuel cars to other vehicles on the road gives us a good idea of how they measure up GHG-wise under a life-cycle analysis. This graph does just that:

The fact that the majority of the greenhouse gas emissions from hydrogen fuel cell vehicles comes from fuel production is a promising sign because these emissions can be mitigated through the other forms of production, which are being researched and developed currently. On the other hand, the vehicle operation emissions for gasoline, diesel, and hybrid cars are hard to mitigate and are here to stay.

Could lead to economic development (Pro)

The hydrogen fuel cell industry has a lot of potential. Innovation and implementation in the vehicle sector for hydrogen could mean lots of jobs in that sector as well as in various other areas. These devices could be used to propel many forms of transportation like buses and trains as well as stationary engines. Manufacturing jobs could be formed for building the fuel cells and vehicles that utilize them as well as fuel station construction jobs.

References

Cradle to Grave Lifecycle Analysis of Vehicle and Fuel Pathways. Department of Energy. 21 Mar. 2014. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

“Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles.” The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, n.d. Web. 05 May 2015.

Author: Drew Beyer

Editor: Justin Pié