Global Climate Change

Hydrogen Electric vehicles use natural gases like methane to produce hydrogen. As such, there are GHG emissions associated with fuel production. As you can see in this life cycle analysis comparison chart, the bulk of HFVCs emissions come from the fuel cycle. (Insert LCA emissions chart) The good news is this means there is room for improvement for HFCVs regarding their effect on climate change, the bad news is the research accomplished thus far has not developed into anything fruitful or economically competitive with current steam reformation technologies for producing hydrogen.

Environmental Pollutants

From the EPA, “Beginning in the late 1980s, Americans began driving more vans, sport utility vehicles (SUVs), and pickup trucks as personal vehicles. By the year 2000, these “light-duty trucks” accounted for about half of the new passenger car sales. These bigger vehicles typically consume more gasoline per mile and many of them pollute three to five times more than cars.”

The EPA further states that the types of pollutants that come out of these cars’ tailpipes cause smog, acid rain, and adverse health effects like asthma. On the other hand, HFCVs produce one thing out of their tailpipe: H2O in the form of liquid and vapor. This simple fact makes hydrogen fuel cell vehicles extremely attractive in places where air quality is a concern, like smog-ridden Los Angeles, California.

Economic Development

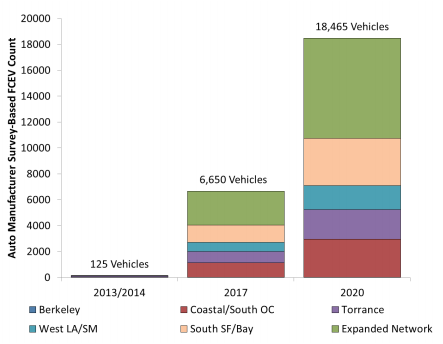

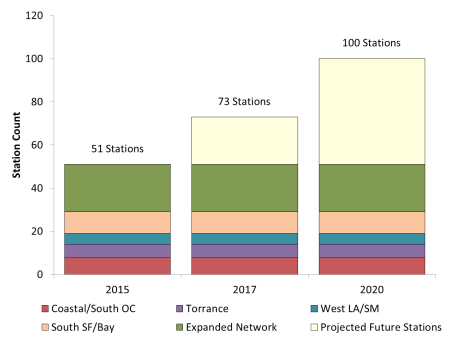

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles have relatively little infrastructure implemented around the world. This means there is immense potential for economic development if the technology catches on, or the implementation is kick-started by government funding at first. Anyway, there are small installments around the country at present. For example, California has implemented hydrogen fueling stations in certain regions. The present status and projections of the numbers of cars and stations are depicted in the following two graphs.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles have relatively little infrastructure implemented around the world. This means there is immense potential for economic development if the technology catches on, or the implementation is kick-started by government funding at first. Anyway, there are small installments around the country at present. For example, California has implemented hydrogen fueling stations in certain regions. The present status and projections of the numbers of cars and stations are depicted in the following two graphs.

See this study for further reading on California’s Hydrogen infrastructure implementation.

The rollout plan is being spearheaded by the state and is still in it’s infancy, but the projections are exciting and it could be a good benchmark for potential future infrastructure implementation.

The implementation of more stations would mean more jobs for construction workers. More cars being produced would mean more manufacturing jobs for cars being built in the US. More competition for gasoline vehicles would drive prices down, making cars more affordable to shoppers.

Inequalities in Access to Energy and Exposure to Harm

Energy access for these vehicles pertains to station location. As of now, energy access is quite low for the vast majority of the country. If hydrogen technologies were to be rolled out like California’s, access near cities would be improved, but elsewhere, access would be non-existent. Infrastructure development is one of the biggest hurdles this technology must overcome before it can be called even somewhat ubiquitous.

Since the exhaust for HFCVs is merely water vapor and liquid water, there is no pollutative harm associated with HFCVs.

Current and Potential Energy and Environmental Policies

In 1992 a five-year program was launched by the US government called the Energy Policy Act. It called for research and development into hydrogen production from renewable energy sources, hydrogen storage and the development of fuel cell technology. (Renewable Hydrogen Energy, 1992)

Then, George W Bush increased hydrogen research and development funding in 2003 in attempts to reduce the US’s dependence on foreign oil.

The Energy Policy Act was amended in 2005, which called for a wide-reaching research and development program on technologies relating to the production, purification, distribution, storage, and use of hydrogen energy, fuel cells, and related infrastructure with the goal of demonstrating and commercializing the use of hydrogen for transportation, utility, industrial, commercial, and residential applications. (Title VIII-Hydrogen, US Gov’t)

In 2009, however, Barack Obama cut Bush’s initial funding for Hydrogen fuel cell R&D due to the length of time it would take for the technology to potentially become economically feasible. (Budget, DOE)

References

“Budget”. Hydrogen Program. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle Deployment and Hydrogen Fuel Station Network Development. Rep. California Environmental Protection Agency, 20 June 2014. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

“RENEWABLE HYDROGEN ENERGY”. Energy Policy Act of 1992. United States Government. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

“Title VIII-Hydrogen”. EPACT 2005. United States Government. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

Author: Drew Beyer

Editor: Justin Pié