A Brief History

Dams have existed as landmarks of ingenuity and resourcefulness since they first were built in Egypt over 4000 years ago. Since then, they have been remodeled and repurposed to serve a variety of functions. However, despite the economic and social benefits of dams, there is growing concern over the various negative impacts that dams have on ecosystems and lifestyles around the world. Considering the fact that there is no universal policy regarding global environmental issues, different areas have varied perspectives on the construction and deconstruction of dams. Thus, it is clear that variables specific to particular dam sites must be evaluated thoroughly in order to assess whether or not dam deconstruction is advantageous and ultimately profitable to communities, as well as ecosystems.

Between 1950 and 1970, about 30,000 dams were erected in the United States (Howard, 2014). Dams seduced the American public with promises of flood control, hydroelectric power, irrigation water, navigation locks, and recreation opportunities, but it did not take long before significant dam pitfalls began to emerge. Around the year 2000, environmentalists and activist groups began to reevaluate this burgeoning trend. Once again, dams began to glow in the spotlight, but this time the media attention that arose was starkly negative. Unsurprisingly, the public began to question the consequences and urgency of dams. Jennifer Brinkerhoff effectively summarizes the contested issue in her article, Global Public Policy, Partnership, and the Case of the World Commission on Dams (2002). She writes,

On the one hand, large dams are seen as an important vehicle for economic development in terms of providing electric power, irrigation for agriculture, and residential and industrial water. Critics, on the other hand, question the development effectiveness of large dams and fault their promoters for ignoring important social and environmental impacts (Brinkerhoff, 3).

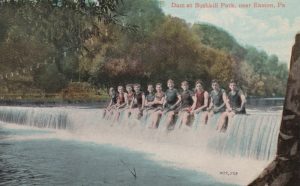

An antique postcard (ca. 1920) shows a row of boys perched on the Bushkill Park dam. The dam was removed in the 1980s during construction of a new bridge on Bushkill Park Drive.

Impacts of Dams

Although large dams are often promoted as green, renewable energy projects, an underlying irony lies in the fact that they are well known to destroy regional biodiversity by blocking the path of migrating fish, and unraveling the ecological web within or alongside a river system that often includes protected species. Large dams are also known to displace indigenous communities, prove risky in terms of investment due to their lacking energy security, and pose health risks related to stagnant water and their potential to fail and cause massive destruction. Further, the large reservoirs emit methane, which contributes to the more pressing issue of climate change. While impacts such as these have caused activists to speak out candidly against many large dams, these repercussions are not apparent in the case of every dam, particularly smaller ones. It is thus imperative to evaluate the circumstances of each unique dam when considering dam removal.

Dam 2 on the Bushkill near Easton Public Works, summer 2017.

Quick River Restoration

It is relevant to note the quick and natural restoration process that rivers undergo once dams are removed. In her article titled, The Long Road to River Recovery, Elizabeth Brink writes, “[I]n nearly all cases where dams have been removed, recovery of ecosystems and fisheries has been remarkably rapid.” (Brink, 2011). Similarly, the revival of a riverbed often opens potential for new green spaces, which can have beneficial social impacts by bringing communities together in a new space and offering them recreational opportunities. Further, in regards to restoring fish habitat, “dam removal does not require a constant input of money and technology to maintain a functioning, healthy ecosystem, unlike alternatives such as fish passages and barges” (Higgs, 2002, 10). These facts gives fuel and reason to the environmental leftists fighting against dams, and also instills hope that a more organic and sustainable future is possible.

Piles of rock mark the spot where the Hughesville Dam once stood on the Musconetcong River. An effective small dam removal project in PA. Photo from Emma Lee/WHYY retrived from StateImpact Pennsylvania

References

Brink, Elizabeth. The Long Road to River Recovery. International Rivers, 2011, www.internationalrivers.org/resources/the-long-road-to-river-recovery-1673.

Brinkerhoff, Jennifer. (2002). Global Public Policy, Partnership, and the Case of the World Commission on Dams. Public Administration Review. American Society for Public Administration

Higgs, Stephen. The Ecology of Dam Removal: A Summary of Benefits and Impacts. American Rivers , Feb. 2002.

Howard, Brian. DamNation’ Film Wins Enviro Prize and Shines Light on Dam Removal. National Geographic Blog.” National Geographic: Changing Planet, Mar. 2014, blog.nationalgeographic.org/2014/03/31/damnation-film-wins-enviro-prize-and-shines-light-on-dam-removal/.