I have really enjoyed the in-class presentations so far. I felt as though each presenter took it upon themselves to teach the class something important and specific about the film theory they are studying. Everybody had well thought-out arguments with a substantial amount of support and reasoning behind them. I believe that Maya Deren can easily be argued as an auteur along with Scorsese and DiCaprio as co-auteurs. I loved the discussion on adaptations and the different approaches to the horror genre. Because we all had a little bit of prior knowledge to the subjects, the presentations helped to solidify the arguments and theories and it was fun to see what others deemed important. Even during my presentation, I was able to learn a little bit more about my own analysis by the post-presentation discussion questions. I was asked what I felt was the most successful combination for a parody film. A parody film is a hybrid of a comedy and another genre, and because a horror is meant to scare, poking fun at it results in a much different reaction by the audience. I chose this as the most successful, and most obvious, type of parody. I was also asked if parody films are meant to leave the audience with the same message as the original film, and my answer was no. The emotions of the audience after seeing a film tell a lot about what they will take away from it, and being scared/sad about a story is much different than laughing at it. I believe that important messages can still be presented in parodies, but these messages vary from the original films intent.

All posts by Samantha Volk

“People…love action, Not this talky, depressing, philosophical bullshit”

Watching it for the first time this weekend, Alejandro Inarritu’s Birdman (2014) is what I would call the definition of a film major’s movie. Filmed in incredibly long takes and minimal cutting, Birdman has done what I have seen no other filmmaker do since Hitchcock’s Rope, although, unlike Rope, Birdman felt very little like a stage production even though, ironically, it was about a stage production. This was prevented by jumping through time much like the human brain, which is what most film’s do and what stage productions fail to do realistically. The one liners in Birdman simply blew me away in terms of film stereotypes and film language. When Sam (Emma Stone) confronts Riggan (Michael Keaton) at the thirty minute marker, she says that he doesn’t like twitter and doesn’t have a Facebook and that because of this he “doesn’t exist” and he doesn’t matter. In this day and age with technology being such a big part of our communication process, it is hard to get by without some sort of relationship with the internet. This line also points to the fact that so many people become famous through social media sites like this that because Riggan does not have one, he isn’t important and literally does not exist in the social media realm.

Another great line was when there is a voice overlay of Riggan speaking as Birdman telling the older, grown up Riggan about what audiences want to see. He says, “people, they love blood. They love action. Not this talky, depressing, philosophical bullshit” and I think this draws attention to the direct comparison between moviegoers who go simply for entertainment and stimulation and moviegoers who go for well-made films and relevant messages. This scene includes an incredible amount of special effects and animation that is fast-paced and widely entertaining and confusing, which makes it captivating; a satirical backdrop for the line about action film.

A noteworthy moment comes when Keaton speaks with the production critic (Lindsay Duncan). I believe this to be a critique of art critics, more specifically those who bash or promote works of art based on the popularity, history, money, etc of the artist rather than for the work itself. While this reporter is a female with probably the most power in the entire film, other females represent the lower side of the totem pole. For example, Lesley (Naomi Watts) is almost raped on stage in front of an audience and she asks a coworker, “why don’t I have any self respect?” which is interesting because of the inserted word “self” when she is complaining of a male coworker taking advantage of her. Laura (Andrea Riseborough) responds with the line, “you’re an actress, honey.” The two share a moment and Laura praises Lesley and before long Riggan walks in, praises Laura, and leaves. She is left glowing with the admiration of the male star. The two females then make out. This pokes fun at female representation both in film and in the entertainment business.

Along with many other significant moments, I enjoyed the film’s use of method acting for Mike Shiner (Edward Norton). It was a subtle, but serious way, to show the consequences of method acting. Mike gets drunk on stage in front of a full audience, he abuses Lesley, he can only get hard in character, and he orders a tanning bed. Riggan even later says, “That’s you Mike. You’re Mr. Natural.” Cinematic realism then plays into the mix with Riggan pulling the trigger on himself, blasting his nose off during his opening night. He ironically has to wear a face mask of plaster and bandages that look like Birdman’s mask and that image is the last we see of Keaton.

Richard Dyer’s “White”

Though lengthy, I found myself engaged with this article throughout the entire thing. The information was relevant, true, and well supported. Dyer’s main purpose is to use Simba (1955), Jezebel (1938), and Night of the Living Dead (1969) to prove that whiteness is related to order, rationality, and rigidity while blackness is related to disorder, irrationality, and looseness. However, he also makes clear that these films attempt to contest white domination and expose the idea that while white people hold power, they are materially and emotionally dependent upon black people.

To introduce his thesis, Dyer explains that “whiteness” isn’t generally seen as anything in particular because nobody studies the majority, proving that studying minority groups makes it seem like they are not part of the norm. He says that whiteness had a property to be everything and nothing, making it a hard concept to grasp. The only way to study whiteness, is to also study minorities so there can be a comparison. When talking about cinema, white people must be divided down into groups such as “English middle class” or “Italian-Americans” and if they aren’t, they are just considered “people” rather than “white people.” Dyer brings up that mainstream cinema should be analyzed in the context of the “commutation test,” attempting to put a black actor in a white role and see how well it works. Dyer asks the question, what does this say about whiteness if a black man cannot play a white role?

Simba: Dyer explains that this film shows the binarism between black and white and that this is represented through mise-en-scene, lighting, sound, and action. Also, the editing of the film is used to calm and stress the viewer in direct correlation to what is shown on screen. This can be seen in the meeting scene on page 828. Dyer later explains that there is a repeated failure of narrative achievement by white characters creating a sense of white helplessness. On page 831, he rounds up with a quote that reads, “Simba is, then, an endorsement of the moral superiority of white values of reason, order, and boundedness, yet suggests a loss of belief in their efficacy.”

Jezebel: Dyer explains that compositionally, black people generally begin scenes by being on camera first and also act as a dominant image in each scene, interrupting moments where the viewer is watching white interaction. They do not serve a very dramatic function but play an essential role. Here Dyer begins his belief that black people have more life than whites because they are more natural and white people are too caught up on thought. To show this, Dyer shows the growth of Julie, the white female protagonist, throughout the film. Julie starts out as wild and free, her inner blackness as Dyer calls it, and ends the film with very little movement. She asks her black maid, Zette, to see who has come to visit and the camera follows Zette as she runs around and is lively while Julie is still and calm and lifeless. As a final punch, Dyer talks about the singing scene at the end of the film and how only specific feelings can be expressed through black people. He gives examples of frustration, anger, jealousy, and fear and says “there is no white mode of expression” for these “pent-up feelings” and they can “only be lived through blacks.” He then sums up with, “The point of Jezebel is not that whites are different from blacks, but that whites live by different rules” (834).

Night of the Living Dead: Dyer makes a nice segue to begin this film’s analysis by saying, “If blacks have more life than whites, then it must follow that whites have more death than blacks” which in this film, is very true (834). All the zombies are white people and living whites are mistaken for them frequently. Dyer then makes the comment that the film may be a metaphor for both white people and the USA in general. The main character is named Barb, she has pale skin and blonde hair and has the same name as the best-selling American doll. Dyer notes that you can kill the zombies through their brain. Another hint at the white obsession with thought and knowledge rather than emotion and body. The protagonist of this film and it’s sequels is a black man. This says that blacks are in control of their bodies and can survive alone while whites have no control over their bodies unless they are zombies, and in that case they hunger for white brains.

In conclusion, Dyer really makes no conclusion. He instead brings up a question on why glamour lighting in Hollywood is fitted for the white female. It is designed to make her transparent, almost hiding her flesh and blood. Because of this, blacks are more difficult to photograph. He also says that the white ideal that embodies all heterosexual men is the white female.

Brokeback Mountain

I am a little ashamed to admit that before watching this film I referred to it as “the movie about the gay cowboys.” However, in my defense, if I ever brought up the name of the film the responses I would get from friends would always be “oh that’s a movie about gay cowboys” so I had very little other information to live off of. With that being said, I am a big supporter of what the film does and will defend it any chance I get by saying “it is a film about two cowboys who may be bisexual, but even that is open-ended and left for interpretation.” Even if that answer is less appealing, it is far more truthful than saying Brokeback Mountain (2005) is simply a film about gay cowboys.

In the first few minutes of the film, a clear male gaze is established. Ang Lee takes the traditional image of a man watching a woman and attributes it to Jack (Jake Gyllenhaal) as he peers over at Ennis (Heath Ledger). Voyeurism is also explored by having Jack look at Ennis in his side mirror without Ennis realizing it. In this scene, no words are shared. The technique and effect is genius. Later in the film, “gazes” are touched on again by having the animals constantly watching/in the presence of the cowboys with no reaction to their homosexual acts. The gaze is also seen again by the boys’ boss (Randy Quaid) watching them through binoculars and also by Ennis’ wife (Michelle Williams) when Ennis and Jack hookup for the first time after four years.

As the film progressed, I made note of any clear feminine/masculine characteristics the men had. I noted that Jack was seen several times carrying a baby sheep who was unable to travel without support. This is a motherly quality. Ennis went “shopping” for their food. When he arrives late, Jack asks “where the hell you’ve been?” Jack then attempts to clean Ennis’ face. Jack complains about “commuting four hours a day” and that he’s “pretty good with a can opener” but “can’t cook worth a damn.” This scene/several scenes couldn’t help but remind me of the conversation between a married couple. By this point, there is little obvious homosexuality, but the commentary plays on the idea that the two have/will have a relationship closer than friendship. Throughout the rest of the film, the roles of each male shift, making the two seem balanced between feminine/masculine qualities rather than having one male dominate the other.

A few minutes more into the film has Jack showing Ennis his belt buckle, or as it can be read, drawing Ennis’s attention to his crotch region. Following this, Ennis tells a story and admits it’s the most he’s spoken in years. This is an acceptance of Jack’s gesture. After the two bond, Jack orders Ennis to sleep in his tent that night and this kickstarts the first sex scene. Interestingly enough the boys the next day share a conversation about not being queer and they agree that it’s nobody’s business but theirs. At the same time, there are animal eyes on the two at all times and a sheep ends up dead. This could be seen as the killing of innocence, any opportunity the men had to live “normal” straight lives.

When speaking to Joe (the boss) about the illness of his uncle, Jack says, “not much I can do about it up here” in which Joe replies “not too much you can do about it down there neither, not unless you can cure pneumonia” and I took this as a direct hit to Jack’s homosexuality. Joe is telling Jack that he can’t do anything about his homosexuality in the real world unless he can change the way the rest of the world sees it, or unless he can cure himself of it. The last few seconds of the film show Ennis admiring the bloody clothing that the boys wore when they fought. He then straightens an image of Brokeback Mountain. I am still unsure what this means, however, if I had to guess, I think it is Ennis’s contribution to straightening up the world and how they see homosexuality. Throughout his life, he has fought the idea of it and has been told against it, but I think this final act serves as his acceptance of it and inner-hope that someday the rest of the world will be as open and accepting as Brokeback Mountain.

Feminism Class Readings

Mulvey’s article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” had me replaying film after film in my head to find moments that matched scopophilia, voyeurism, fetishism, and narcissism. The concept of the audience being a Peeping Tom is a drastic, yet a highly accurate, accusation. Reading “her visual presence tends to work against the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation” immediately recalled every James Bond movie or James Bond spin-off I had ever seen. Reading farther made me increasingly aware that major genres including the western and gangster do not have major female roles. Fairytales have passive women generally in need of male heroism. Action films are based around the accomplishments of male characters. The change in feminism over the years began with a desire for equality in rights, then equality in the workplace, to a shift in focus in more than just middle-class white women, and finally the modern take on equality in spirituality and religion. I have watched Mamma Mia (2008) an incredible amount of times, it being my favorite movie and one I take on every trip, and believe it does successfully go against the modern male endorsed film. I look forward to class discussion on how this film works in terms of the feminism movement.

The Celebration as a Dogme Film

The idea of a Dogme film is to retain a “Vow of Chastity” or a promise to create a film as innocent, pure, and untouched as possible. Looking at The Celebration (1998), directed by Thomas Vinterberg, the ten restrictive rules established in the Dogme 95 movement can be found. The main location of the film is a home where the protagonist of the film grew up with his siblings. This home, the forest around it, and the road leading up to it are pretty much the only footage in the film, this means it could have easily been shot on location and not in a studio. The camera is clearly handheld. This can be seen in a few of the beginning exchanges between Michael (Thomas Bo Larsen) and Christian (Ulrich Thomsen). Also the shot where a car pulls up the driveway, a camera follows it, then points up, and falls back down to follow it again, sort of like a rainbow pattern. Another cool handheld shot came from above and below a stair banister to see the siblings walk upstairs. While filming at night, the images on screen were extremely dark and only illuminated by the light of the sky, which was very little. This can be seen when Christian frees himself from the tree he was tied to. I find the idea that Dogme films may not contain superficial action interesting because it immediately made me think of the sexual abuse information and how it was a director’s choice to not flashback to those moments or even show the father abusing the sister before she committed suicide. It also makes it clear that Helge (Henning Moritzen) was physically beaten on screen by Michael which intensifies the situation. Rereading this description on no superficial action, I am realizing now that the sex scene must have been live action… All of these characteristics are interesting in combination and seem to work. I would like to know why the Dogme 95 movement was so impactful and why filmmakers felt it was necessary to create films in this format.

Run Lola Run Color Repetition and Animation Impact

Though generally a film coupled with live action shots and animation tends to lean towards cheesy or a children’s TV show that attempts to teach a moral lesson, Run Lola Run (1998) directed and written by Tom Tykwer, did a hell of a job in telling a story fit for a much different audience. The film is full of puns, hidden messages, motifs, and more, making it an incredibly gripping tale that is made stronger in my opinion by the inserted animations. Because of a reoccurring animated scene where the camera appears to jump into a TV, it is clear where the three versions of Lola’s (Franka Potente) stories begin.

This scene replays three times, each a little different. And these differences are significant in the tale. The first time we are introduced to Lola running down a winding staircase with a boy and a dog waiting at the top of one leg of it has camera zoom in on the dogs teeth. Upon asking what this may mean in class, somebody brought up the cliché “time nipping at your heels.” I interpreted it as another reference to the clock ticking away in Lola’s twenty minute adventure. During Lola’s second try at getting things right, the camera zooms in on the teeth of the boy. Another reference to time nipping at her heels, but this time it’s more about dealing with people to get her way, which turns out even worse than the first try when her conversation with her father (Herbert Knaup). She ends up robbing the bank. The third time this animation is replayed, Lola jumps over the barking dog and barks back, signaling that she will overcome time in this final attempt.

Something else I noticed from the start of the film, whether it was the red hair that set it off or the red phone, was the repetitive color scheme of the film. Reds. Greens. Yellows. Over and over and right in your face. Tykwer didn’t mean for it to be subtle, he meant to send a clear and unmistakable message–another reference to time. Red clearly means stop, and green means freedom or go, so yellow must fit right in to mean a slowing down of time or perhaps a tough decision that must be made. Just to reiterate the repetition: the red mise-en-scene includes Lola’s red hair, the phone, the tint over the screen while Lola and Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu) share a conversation while one of them is dying, red doors and windows, car, biker’s shirt, the Apotheke sign, designs on flags, and more. The green mise-en-scene includes the polizei, the bag, money, and the green picture. The yellow mise-en-scene includes the phone booth, yellow stores, train, and car. The emphasis on the essence of time is literally everywhere in the film, strengthening the message and film as a whole.

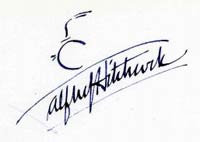

Hitchcock’s Signature

Something else I thought was really cool came in the discussion of Alfred Hitchcock in the Auteur Theory chapter. When talking about themes it went into depth on Hitchcock’s fascination with the eyes, and how he puts close-ups of faces with some strange abnormality in the eyes in each of his films. By doing so, he points to the fact that he believes what a character thinks or needs is revealed through the eyes, the windows to the soul. He relates the murderer, his prey, and the audience using these techniques by having the audience enter the violence through the eyes of the victim. Tracing back to his childhood, Hitchcock felt like he was an outsider along with evidence of misogyny and episodes of sadism, all seen as themes in his films.

To be a great filmmaker, you really cannot be average. You have to make a name for yourself, and sometimes that name comes more from what you’ve endured naturally than what you have made for yourself out of hard work. In the Hitchcock passage I read, “His striking way of signing his name was made up of a series of eight strokes of his pen to create a silhouette likeness of himself,” and I immediately googled his signature.

It’s fascinating because looking at the signature at first glance, it looks like nothing but a few random lines above Hitchcock’s name. Looking deeper you are able to see him within it. This is just like Hitchcock’s filmmaking. Upon first view, a film merely looks like a project by a filmmaker. Looking deeper, you can see the filmmaker in the work itself.

Tim Burton

Reading the auteur theory chapter in “Understanding Film Theory” brought me back to several childhood memories. Tim Burton was a favorite of my brother’s. I remember him telling me about the sort of triangle that Tim Burton had with Helena Bonham Carter and Johnny Depp. He loved Johnny Depp and this got him hooked on Tim Burton films. Meanwhile my father was not a fan of Tim Burton in the least bit. He disliked Johnny Depp’s characters and the gloomy and gruesome plots that Tim Burton tended to lean towards. Although I have always been aware of the clear correlation between Tim Burton and Johnny Depp (if you put the two together there will be some kind of depressing story, lots of black, and emphasis on night and blood) I didn’t recognize these to be Tim Burton’s stylistic traits and why he was drawn to them. This explained to me why my brother had a strong liking to all of his films while my dad was the complete opposite.

This chapter explains in great detail each technique and choice Tim Burton makes. As a director, he consistently falls between Horror and Fantasy which in turn requires shadows, curves, angular objects, and a surreal nature of storytelling. The use of Johnny Depp in both Edward Scissorhands and Sweeney Todd draws a direct parallel between the two stories and stems the latter film as sort of a ghost of the former. The costuming and makeup also remains consistent with a feel of dishevel, chaos, and death, but also sympathy for the outcast. Digging into Burton’s childhood tells us that he had a period of his life that he was a loner and where he found himself lost in an imagination where he related to the monster, the outcast, and saw the monster as having a bigger heart than what appears. Sweeney Todd is one of my favorite films. Even though he is a serial killer, I find a connection with Johnny Depp’s character because of the way the film is set up and the message portrayed by Burton. There are series of flashbacks where we see a man of political power stealing Depp’s love from him unjustly. Instead of completely rejecting Depp’s character as being a psychopath, we relate to him because he feels love, a natural emotion that we all have felt. Without this connection, the film’s message would be much different and it would be received much differently.

“Ontology of the Photographic Image” by André Bazin

Beginning his essay, André Bazin dives right into the practice of embalming, how ancient Egyptians used to mummify bodies and keep them from decaying. He compares this practice to the birth of the plastic arts. He states that there is a basic psychological need in man to outwit time and preserving a bodily appearance is fulfilling this desire. Because, however, pyramids and labyrinths could be pillaged, statuettes were developed as substitute mummies in case anything were to come of the real one. This is the birth of the idea of “the preservation of life by a representation of life.” Rather than requesting to be embalmed, Louis XIV is an example of an eternal image that is set to survive via painting. Veering away from this, Bazin makes the assertion that within today’s society (keep in mind he is referring to the mind around 1945), we are no longer solely concerned with survival after death but also with the creation of an ideal world with its own temporal destiny.

In the fifteenth century, Western painting turned from a concern with spiritual realities and aesthetics to one in which spiritual expression is combined with an imitation of the outside world that is as close as possible to reality. The camera of Niepce was credited to be the invention of photography in the 1800s, meaning things could, and began to, exist as we see them in reality. This left painting torn between two ambitions–the expression of spiritual reality and symbol and the desire for duplication of the world around us. Bazin continues to explain that the desire to see reality, though it is merely an illusion created via painting, is a mental need and realism in art is caught between the aesthetic and a deception aimed at fooling the eye. This being said, photography and cinema have freed mankind from the obsession of illusion in painting because they themselves satisfy our obsession with realism.

Bazin compares two filmmaking styles, the style concerned with an image and the style concerned with reality. A photograph is of a specific moment in time and a specific place, while art can be of any moment in any place which is why Bazin argues that a painting is more eternal than a photograph. Photography ranks high in the order of surrealist creativity because it produces an image that is a reality of nature, namely, an hallucination that is also a fact. Thus, as a final blow, Bazin makes the assertion that photography is the most important event in the history of the plastic arts and then leads us into his article on the development of the language of cinema and how we analyze it.