This past weekend, our class was immersed in two starkly contrasting cultures of nature. Conservation and the role of humans in nature are defined in opposing ways at Hawk Mountain and Cabela’s. While Hawk Mountain has a rich history of conservation, even attracting the likes of Rachel Carson, Cabela’s marketing strategy of protecting the environment in which we hunt is flawed. Because Hawk Mountain prohibited hunting since the early 1930s and began to collect data on migrating raptor populations, Carson was able to see trends of decline in the number of immature eagles. Carson linked this decline to the use of DDT; eggs were not hatching and newborn eagles were dying rapidly. Being a unique sanctuary along a raptor migration path, Hawk Mountain became a case study for Carson’s Silent Spring. In opposition with these concepts of conservation, Cabela’s conflates a respect of nature and conservation with the ability to take from nature what you can and rise as a victor, taxidermy trophy and all.

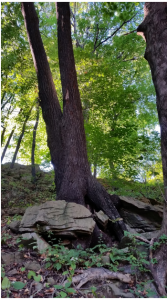

According to the Hawk Mountain Visitor Center, “nature” is “The world outside our window.” This is phrase was written above the windows located in the back of the visitor center where guests can sit and watch birds gravitate to the feeders placed outside. To the Hawk Mountain Visitor Center, nature is to be viewed and conserved. It is picturesque – worthy of a calendar, puzzle, or picture book. This concept of nature as a picture was also evident in the Golden Eagle presentation when the eagle was held in front a large crowd and the bird handler assured viewers that they would have the opportunity to take photos.

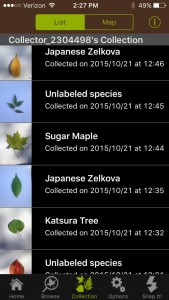

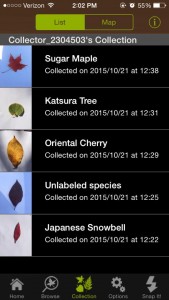

At the Hawk Mountain Visitor Center, the aftermath of mass hunting of raptors was shown in a dramatic black and white photograph – an image that prompted Rosalie Edge into action in founding the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary. This starkly contrasts with Cabela’s promotion of hunting. In the store, a photograph placed beneath a large elephant mounting shows a member of the Cabela family smiling proudly with his kill behind him. Though admired in the form of a picture, nature at Hawk Mountain is respected in its living state as something to be watched and cared for. The regulations to protect raptors in the sanctuary, birdwatchers stationed with binoculars, and HMS staff tracking population counts demonstrates this respect.

Cabela’s provides customers with opportunities to interact with dead, constructed forms of nature. In this way, Cabela’s becomes a destination. Nature in this constructed and conquered form becomes a museum of interactive entertainment. Not only are guns sold, but you and your family can pay a visit to the Gun Library. Patrons can play at the Wilderness Creek Shooting Gallery or shoot some bucks in a video game at the entrance to Deer Country. Our group was lucky enough to catch the afternoon Diver Dan show in the Aquarium. During the show, Diver Dan scooped of the largest catfish in the tank and jostled it around, opening its mouth for the viewers to see inside. The shooting games, the mounts and glorified hunting stories presented in Deer Country, the photo of Cabela and his elephant, and Diver Dan clearly demonstrate Cabela’s overarching theme of man dominion over nature, the “sportsmanship” that is promoted is a competition of man versus nature.

At Cabela’s nature is respected as a challenging arena of sportsmanship – a place to conquer. Animals are hunted for “bragging rights” as one sign at the front of the store bluntly states. Cabela’s true narrative of conquering nature clearly overrides the companies attempt to come across as an environmental steward. When leaving Deer Country, visitors are confronted with a sign stating, “Ensure the beauty of the outdoors. Support wildlife conservation. Meanwhile, trophies for conquering nature – in the form of taxidermy – are displayed in their still, lifeless form posing the recreated scenes of the nature from which they were “taken” (i.e. in Deer Country and on the central-store mountain of miscellaneous game). These posed animal figures give “silent spring” a whole new meaning. Why, after all, would we “take” animals out of nature to have them pose in a plastic recreation of the environment in which they once lived? The store uses the word “taken” in the labels of where and how each animal was hunted and killed. Using “taken” over “killed” further emphasizes the concept of nature as something to be conquered and attempts to avoid the negative association of hunting with purposeless killing.

This narrative is set up from the time one first approaches the store and into the depths of Deer Country. The statue in front of the store, entitled “A Leaf On a Stream,” presents the image of the American frontier with a pioneer and a Native American together on a canoe. The plaque explains that both cultures sought ways to survive and overcome the challenges of nature. Woodsmen such as Daniel Boone “made the woods, mountains, ad rivers ours,” according to the plaque. Paired with this narrative, the most emblematic image of the Cabela’s experience can be found in Deer Country. I saw children experiencing the museum of constructed nature. They reached the point in the exhibit where there was a model cabin with an artificial human sitting outside by a fire pit. A young boy pressed a button and the human figure became animated and stated, “Took some mighty fine woodsmanship to get them with a bow and arrow. Those bucks were smart. They don’t get that way [large and strong] by being stupid.” It was startling to see that the only animated portion of the museum was the human. Everything else was silent and posed.

These images of Cabela’s contrast with scenes at Hawk Mountain, where humans still relatively still to take in the action of raptors around them. The predominant image of Hawk Mountain is the visitors perched on the peak binoculars in hand, sitting on rocks, announcing the arrival of new groups on birds that are gliding along their migratory path. People sit for hours with a supply of snacks and a thermos holding a hot beverage. In terms of similar images, however, captive animals become a spectacle for visitors. This is seen in the case of the wounded Golden Eagle and the catfish displayed at the Diver Dan show. In both of these cases, the animal, when taken out of its natural setting became a form of entertainment, used by humans as an attraction. Viewing animals as play things can cause people to develop a problematic mentality of our dominion over other creatures.

At Hawk Mountain, birds of prey are viewed through binoculars and in photographs as majestic and powerful creatures. This is a reverence similar to that which is conveyed in Abbey’s “Watching the Birds.” This is a stance that is not often taken in other parts of society where raptors are fear evoking or somewhat repulsive. When taken out of the distanced bird watching context and placed in the context of being seen up close, attacking prey or feasting on dead animals, raptors may evoke a feeling of disgust. Mary Oliver discusses a more complex yet dark feeling toward vultures when she states, “Locked into the blaze of our own bodies/ we watch them/ wheeling and drifting, we/ honor them and we loathe them/…however ultimately sweet/ the huddle of death to fuel/ those powerful wings” (1983). Eagles, however, evoke a feeling of patriotism and pride in our landscape since they are a national symbol. While fostered and protected by Hawk Mountain, certain birds of prey would be fair game to hunt in the eyes of Cabela’s, just as an elephant would be, despite the many efforts to protect such animals.

It is clear that Cabela’s is marketing heavily toward a “masculine,” anti-gun control demographic of white men in a higher socio-economic status. Whole families do go to enjoy the Cabela’s experience so there are items to appeal to children (hunting toys, stuffed animals, and shooting games), young girls (pink camouflage attire and pink toy guns), and women (jackets and home goods). The signs around the store depict white men hunting, fishing, and earning their “bragging rights.” Miscellaneous items around the store tout the second amendment and the masculinity associated with guns – mainly in the form of wall hangings and t-shirts. Cabela’s attracts a higher socio-economic class that A) has the means to spend experiencing the store and spending leisure time hunting and B) the money to afford the high-end, pricy gear and décor available in the store. The store even provides people with the opportunity to purchase home butcher shop equipment such as meat grinders and dehydrators. There is a fee to enter or become a member of Hawk Mountain, which may deter some families from going, however this fee is certainly not comparable to what one would spend during a trip to Cabela’s.

The contrast between Hawk Mountain and Cabela’s relationship with and definition of nature is certainly apparent. These places represent opposing narratives of how humans interact with nature – as picturesque and necessary to protect versus being conquered through sport. This trip presented to extremes of the American human relationship with nature though there are certainly other cultures and relationships that are part of the spectrum of interaction.