Twice I thought I might drown in the Mississippi River. For someone who grew up more or less near The River—my hometown was known as a river town—I had little experience with it. I never felt compelled by it; never felt particularly lucky or unlucky to be within its reach. My parents showed no interest in it; our family had no money for a boat and we never spent any time along its banks.

When I was nineteen or twenty, I was pulled from the river by Mike Heiderscheidt, a co-worker of mine who made a spectacular dive off our boss’s boat to save me. Dick—his real name—was a weasel and a prick, but the boat party was his attempt to show he was not. It was a weird night. It didn’t take long for everyone on board to get sloppy drunk on the boss’s beer and booze, and things started to happen that I didn’t want to see. People were pitching beer cans into the water and laughing way too hard at jokes that weren’t funny. One of the 60 year-old office ladies was sitting on Dick’s lap letting him squeeze her like a stress toy. I looked over and saw my friend Chris, a hemophiliac in fragile health, smoking cigarillos he’d been given by the creepiest of our night managers. Chris caught my eyes and before I uttered a word told me: “Shut the fuck up.” I thought I’d have a better time in the water, so I jumped in for a swim.

The river was a relief, except for the odd beer can floating by. I was treading water about 20 yards off the end of the boat, watching the raucous party of Captain Dick. Everything was fine until a big wave hit me and I took a mouthful of brown water. In fact, everything was still fine, but Heiderscheit didn’t think so. I don’t remember any fear or even the notion that I might be in trouble. What I do remember was Heiderscheit in action.

Someone had seen the wave hit me and called out, asking if I was OK; I waved back, but was coughing out what I’d just gulped. I saw Mike grab a life preserver and launch himself through an arcing dive into the water. It was a pretty dive, and in four seconds he was shoving the orange vest in my face. I was soon back on the boat, and for the rest of the night kept wanting to jump back in. Only through the insistent warnings of my shitfaced co-workers did I begin to consider I might have been in danger.

I guess that was the second time the Mississippi almost got me. The first time was when I was about ten, when my brother and I went out in a boat with our crazy Uncle Red. I loved my uncle, who was a river fisherman, and the few outings he took me along on were, for me, all about spending time with him, not about any special passion or intimacy I felt for the river. My dad didn’t like Red much, thought he was irresponsible and a drunk—which he was—and he didn’t like to give us too much unsupervised exposure to him. Once when we were all fishing with Red below the bluffs of Eagle Point Park, on the upstream shore near the big Lock and Dam Number 11, my dad screamed at me to not stand so close to the edge of the water. “You could fall in,” he warned, “and you’d go right under those big doors and that would be it for you!” I edged back, pissed. Every time I saw the Lock and Dam after that, I stared at the doors and the white, choppy water roiling out of them. I learned to fear them and repeatedly imagined being sucked beneath the wide metal plates, knocked out and choking to death under their suffocating, silty pressure.

I don’t remember how we were allowed out on the boat with him, but there we were bumping directly toward the Lock and Dam, Red maneuvering the Evinrude to a spot just below the big gates so that we could fish the edge where the churning water met the calm. Even though we were anchored safely downstream from the great wall of concrete and metal, I could see the violent water sucking driftwood back toward it, banging the flotsam up against the silver face of the dam. My brother Scott and I fished but had no hits, all the while I stared at the maelstrom in front of me, my dad’s words conjuring images of my destruction in my head.

Red decided we needed to reposition the boat to get us closer to the dam, so we pulled up the cement anchor and waited for his word as he edged the aluminum boat upstream. The idea was to go to the edge of the rough water, then throw out the anchor so we could try the vein where the fish were holding up. When we reached the border of rough water Red cut the engine, then told my brother to throw the anchor off the bow—only Scott was not ready for the throw when Red called for it. The boiling water spun the boat around and as Red yanked the cord for the restart, the anchor rope wound about the propeller and killed the engine. Powerless and without an anchor on the bottom, the boat was sucked toward the dam. Quickly we were being jostled and tossed and in a few seconds we were up against the doors. Metal boat smacked steel wall, scraped up its side and scratched back down.

The arms of each huge section of the dam protruded out into the river so that up against the doors, you were in a room with three towering sides. The only exit was back out, through the white water. I was sitting in the mouth of the monster that wanted me in its belly. And now it had me. All it needed to do was open wide and swallow.

My brother was white and rigid, and Red was bent over the back of the boat cutting through the layers of rope that had the propeller in a death grip. The roar of the water surrounded everything and if any words were spoken I never heard them. To steady myself, I reached out and touched the malevolent silver face of the dam, pocked with huge rivets no boy was meant to touch.

But I didn’t even get wet.

After several banging minutes on the belching water, Red had the propeller free and the outboard did its job. I couldn’t hear it, but the blue smoke was there and the world brightened as we moved out from the shadow of the walls. I looked back to see the monster, still spitting its froth from its metal teeth, shrink behind us. I could hear the Evinrude again now, and see my uncle mouthing something toward us. He was saying it was time to get off the river.

Now, when I return to my hometown river town to visit my mother during the holidays, I always make it a point to drive to the river just below the dam. Usually the season is cold enough for the water to have iced over. And there you see the eagles—dozens of them—bald eagles sitting on the ice’s edge, staring into the open water and looking for fish to rise. The black water remains open for a hundred yards below the dam, then eventually ices up as the water flattens and slows. There, on that sharp edge of liquid and solid worlds, sit the eagles. From where I sit, they seem to be staring down the metal monster, forever foaming at its mouth.

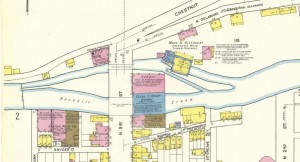

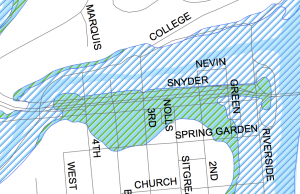

In addition to this, we looked into what used to exist on these sites in the past and perhaps try to find out what happened to those place. We used what photos we were able to find online as well as the Sanborn Maps of Easton from around 100 years ago to investigate what used to be in this area. Specifically, we are interested in examining why there used to be two streams the flowed under the North 3rd street bridge. Attached are some of the photos and maps we found:

In addition to this, we looked into what used to exist on these sites in the past and perhaps try to find out what happened to those place. We used what photos we were able to find online as well as the Sanborn Maps of Easton from around 100 years ago to investigate what used to be in this area. Specifically, we are interested in examining why there used to be two streams the flowed under the North 3rd street bridge. Attached are some of the photos and maps we found: