A miner problem: the struggles of the Ruhr region and de-industrialization.

What’s the largest urban center in Germany? It’s not Berlin, it’s actually the Ruhr area. With 5 million people the Ruhr region is composed of Duisburg, Essen, Dortmund, and about a dozen other cities and municipalities.

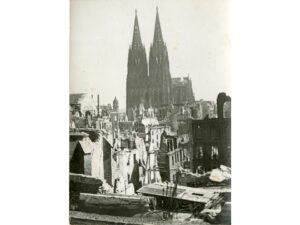

Here’s a picture if you need it.

The history of the Ruhr began about 300 million years ago when enormous ferns grew hundreds of feet tall in the Carboniferous period. Like modern trees, these ferns were composed of cellulose. And so for millions of years, these ferns grew, and died, and grew and died. But the carboniferous period was unique because the bacteria needed to break down cellulose hadn’t evolved yet. So instead of decomposing, the ferns just kinda sat around. Building up year after year, eventually getting crushed into coal.

Then fast forwards some 300 million years, the first coal mines in the Ruhr were opened around 1880. Coal had been mined in the Ruhr region for hundreds of years. At its height in the 1950’s coal mining employed roughly 600,000 people. Since the Industrial Revolution, the Ruhr was the defacto spot for industry in Germany. On the first group trip, we went to Duisburg to visit an iron foundry that operated from 1901-1985.

The foundry, now a park, is an impressive feat of German engineering. It’s massive, hundreds of feet tall. With pipes, and steel crisscrossing overhead. Scaffolding leading up the side of the enormous blast foundries, now lying dormant. One can imagine the noise, see the old rail tracks where carts of iron and coal would be brought in and processed, we could see the carts where the smelted iron would be poured, and the ‘slag’ remnants of the forging process would dumped and taken away to be ground down and turned into concrete. When walking under the labyrinthine collection of concrete, steel walkways, and pipes, it felt like I was walking in the bowels of some great beast, now dormant, but ready to come alive at any moment.

The history of this factory, and the history of the Ruhr region in its entirety, goes hand in hand with the history of Germany. Germany has a long and turbulent history. After the Holy Roman Empire dissolved in 1805, the region bounced around confederations and treaties until the German Empire was formed in 1871. The German Empire almost made it 50 years before it was overthrown in the November Revolution at the end of WWI. After WWI, Germany lost a lot of territory and access to iron. This led to an increase in importation and a rise in iron foundries in the Ruhr. After WWI the German Empire collapsed into the Weimar Republic which lasted for almost 20 years, Germany went through an incredibly turbulent time. Germany faced reparations from France, Belgium, and Britain mostly to pay for the cost of WWI. In 1920 there was a communist workers uprising in the Ruhr region, which was put down by the government after nearly a thousand casualties. This caused a dip in coal production which triggered French occupation in the region. The outrage of occupation, economic instability, and general ineffectiveness of the Weimar Republic led to Nazi ideologies festering.

After the Nazis took power, the Ruhr region shifted towards war preparation. Factories installed air raid shelters. Chemical plants were constructed which could turn coal into oil in an attempt to make Germany self-sufficient for the war ahead.

During the war, the Allies used carpet bombing tactics, since the technology to aim bombs reliably didn’t exist, allied bombers would drop thousands of bombs on populated areas in an attempt to maybe hit something of importance. This led to the devastation of German cities, which can still be seen today. Some neighborhoods that got lucky and survived unscathed look like charming old Europe, and others that got rebuilt after the war look like they were rebuilt as fast and as cheaply as possible, which they were.

After the war, there was some debate about de-industrializing Germany, but with the threat of the Soviet Union, the USA, France, and Great Britain decided that it would be best for a strong West Germany to oppose communism. This led to reinvestment and the Ruhr was rebuilt. Hundreds of thousands of people were employed, and thousands of immigrants moved to the Ruhr region. The work was hard, coal mining was and still is dangerous. These worked often only lived to be 50-60. But people in the region were proud of having honest work, and that is reflected in their culture even today.

On the second day of our trip, and after only one trip to the hospital (read about that story in Andrew’s blog here), we visited a coal mine in the area. On top of the mineshaft itself, was the processing plant where coal would come in to get processed.

However, the Ruhr region faced many challenges post WW2, by the ‘60s there was a coal crisis in Germany, and in the ‘80s a steel crisis, but with no alternative employment, coal mines persisted. The last mine closed down in 2018. The de-industrialization of the Ruhr region led to a high unemployment rate. Some of the derelict factories were preserved, some were turned into parks, and some were torn down.

Now, walking around the small streets and narrow houses, you can see the industry of the past. It’s entwined with very soil and water. Literally. Due to the extensive mining in the area, the ground has sunk by about 75 feet This means that the Ruhr itself, the river in which the whole area is built around can no longer flow and must be pumped into the Rhine. Pumps run 24/7 to prevent the Ruhr Valley from flooding with groundwater and turning into a lake. I couldn’t help but feel sad, walking along the canal of stagnant water that once was a vibrant flowing river, now slow-moving and full of algae and other gunk. And this pumping is an eternity cost. The pumps must run for as long as the 5 million inhabitants want to live in not a lake.

But over the last decades, the region has gone through a metamorphosis of sorts. Dozens of universities have opened. Shalke, a local soccer club (any from Europe please forgive me for writing the word ‘Soccer’) has one of the highest attendances in Germany despite being near the bottom of the second league. There are opera houses, parks, hundreds of kilometers of bike trails, and a great spot to get a $5 döner box. So while unemployment is still high, and the region faces many challenges, the future of the Ruhr post-industrialization looks promising.

Sources and further readings:

https://www.britannica.com/event/Ruhr-uprising

https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/business/ruhr-area-transformation-of-the-coal-region

https://www.germany.travel/en/cities-culture/ruhr-area.html