Policy Analysis (CHP)

Introduction

The policy analysis section of our report focuses on how the influence of internal processes and external incentivizing can affect the political feasibility for implementing Combined Heat and Power on Lafayette’s campus. The purpose of this report is to provide key insights of the current state and future goals of implementing a CHP model on campus. It was important to look at this overall analysis from a political standpoint in order to help identify regulatory factors that are detrimental to CHP’s implementation, and additionally, what would need to change, if anything, in order to make CHP a reality in the future.

Specifically for Lafayette, it was beneficial to identify key stakeholder that would need to be supportive of this initiative in order for it to be successfully utilized on campus. In this section, stakeholders refer to the general methods for implementing change, rather than specific faculty, which is mentioned in the social analysis section of our report. However, these stakeholders do include economic and environmental policymakers at the federal and state level, in addition to key decision-making teams within the Lafayette community.

Problem Definition

From an overarching political standpoint, there are ranges of factors that affect the popularity of CHP. Many of these problematic factors have been widely acknowledged through a variety of studies, some of which are part of this analysis. Because of this, it was important for us to dig into these policies and gauge how much of an impact they may have on the future of CHP at Lafayette. Dr. Mark Hinnells, from the Environmental Change Institute at Oxford, summarizes that this spectrum of challenges can span a range of contexts including, “government policy towards climate change and carbon emissions, energy policy including trading arrangements, planning and power station consent policy, and fiscal incentives” (Hinnell, 2008). Thus, the success of a new technology, such as CHP, is widely dependent on its relevant markets and regulatory policies.

One roadblock Lafayette has faced in past attempts to switch to CHP is the fiscal risk relating to the instability of the natural gas fuel market (the type of fuel Lafayette would be using for CHP). Research showed us that Lafayette is not alone in this uncertainty. In a study published in Applied Thermal Engineering, the researchers reported that as of now, “for CHP applications, natural gas has dynamically entered the market and has become a more profitable fuel compared to oil” (Konstantakos, Pilavachi, Polyzakis, & Theofylaktos, 2012). They went on to say that, “due to unpredictable economic and political factors it is quite difficult to take optimal investment decisions for CHP systems” (Konstantakos et al., 2012). Because natural gas is dependent on international oil prices, the market is subject to severe fluctuations that increase the risk of investment in CHP for many institutions including Lafayette (Konstantakos et al., 2012). As a result, fuel markets and federal incentivizing were included in our scope of analysis, in addition to environmental policy at the state and federal levels. This is a case where the government acts as one of the indirect, yet equally essential, stakeholders in our ‘deal-breakers’ analysis for CHP installation.

Case Study: Dutch Policy and CHP

The Netherlands is a fantastic example of how a nation used government regulations and incentivizing to increase the popularity of CHP. A study in Innovation for a Law Carbon Economy gave an overview of Dutch policy and clearly related it back to conservation efforts and future policy strategy for the United States. The study started with a historical overview of policy development in the Netherlands, and explained that there had been no government action until after 1978. In the 1980’s, the government stepped in and created committees to help increase the number of CHP installations. In the 1990’s, a market broker was established to steady the fuel market, which increased demand for CHP as energy savings increased (Foxon, Köhler, & Oughton [Foxon], 2008). The success of the programming is reflected by today’s numbers, showing that over half of the Dutch electricity is generated by Combined Heat and Power (Foxon, 2008). This market transformation uses, “a mixture of information, incentives and regulations to transform the market for a given product…[and is] a powerful aide to the design of policy over future decades in the attempt to reduce carbon emission” (Foxon, 2008). Each of these efforts to support CHP, from working to decrease carbon emissions to the use of economic incentivizing, are heavily influenced by the stability of the fuel market. Therefore, the stability of the fuel market is one of the biggest factors used in this policy analysis to gauge the feasibility of CHP in the United States and at Lafayette College.

US Federal Policy Analysis

While the United States has been making progress to increase standards and set goals to promote green energy, we still have not reached the level of success that the Dutch have achieved. However, in 1975, Congress passed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), which established a program for “comparing appliances, a labeling scheme, and a mechanism for examining mandatory efficiency standards” (Foxon, 2008). This system set some necessary groundwork for further action. In additions, the Department of Energy (DOE) and the U.S. Environmental Protections (EPA) established the CHP Partnership program and have been working in collaboration to create a “voluntary program aimed at encouraging CHP growth in the United States” (Kalam, King, Moret, & Weerasinghe [Kalam], 2012). More recently, in 2015 Congress passed the Energy Productivity Innovation Challenge Act (EPIC) that requires the DOE to, “establish a voluntary electric and thermal energy productivity challenge grant program for providing support to states” by 2030 (EPIC Act of 2015, 2015). These progressive changes being made at the federal level show that while we may not yet see the direct influence of them at Lafayette, there are influential changes being made that are working with CHP, rather than against it.

Pennsylvania State Policy Analysis

Another aspect of this analysis focuses on the political conversations regarding CHP support within Pennsylvania (or at the state level). The state legislation is important to Lafayette’s CHP analysis because these policies and regulations have a direct impact on the energy market and providers, in addition to the funding and economic incentivizing that is directly related to Lafayette’s ability to enter this green energy market.

State regulations have had a huge influence on CHP because of the complexity between green energy and the grid’s infrastructure. As explained in a scientific report on political barriers for CHP, “the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has authority over inter-, but not intra-state electricity sales, which means that the state electricity policy has an enormous effect on CHP outcomes” (Kalam, 2012). The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission (PUC) currently plays one of the larger roles within the state’s direct influence on CHP initiatives. This team works to balance the needs of energy consumers and providers. They also claim the responsibility of helping to, “foster new technologies and competitive markets in an environmentally sound manner”, which include CHP efforts (Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, 2016). In addition, the 2004 Pennsylvania Alternative Energy Portfolio Standards (AEPS), also referred to as the Clean Energy Standards, requires each electric generation or distribution supplier to supply 18% of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2020 (Alternative Energy, n.d.). These enforced benchmarks make it easier for businesses and individuals to invest in alternative energy, and to our benefit, in CHP. Throughout 2016, the PUC has been taking more direct action to create CHP specific initiatives. For example, in February there was a press release which announced plans to encourage the use of CHP by requiring natural gas and energy distribution companies to: make CHP an integral part of their energy market, increase CHP marketing to consumers, design tariffs to improve interconnection standards, and to consider providing incentives for CHP customer (Press Release, 2016). While many of these efforts are in progress, they are included in this analysis because they inform us of the current state for renewable-energy promotion. As these efforts continue to evolve, the potential for CHP in Pennsylvania will do the same.

Lafayette College Environmental Policy

While Federal and State policies influence Lafayette’s motivations to move toward CHP, the policies and processes for environmental change at Lafayette are one of the most important stakeholders to consider within the whole political context. Without some changes in the energy market, like regulation to stabilize the natural gas market, the ability for Lafayette to choose CHP is restricted. However, once those are sufficiently mobilized, the full weight of the decision-making and feasibility of the CHP model is placed within the bounds of Lafayette’s policies and key stakeholders.

The College went through a period of analysis and policy development to set new goals to move the school towards a greener and more energy efficient model after signing the ACUPCC in 2008. There are statements in this model that support the argument of moving to CHP, such as the College’s commitment to maintenance, as the Energy Policy states that, “proper maintenance is required to ensure the systems operate as efficiently as possible… [and that] operational procedures will [include] resource conservation practices so as to reduce waste and minimize energy expenditure to the extent possible” (Lafayette College, n.d.). The Energy Policy also states that, “energy efficient products shall be purchased whenever possible… [and that] alternative energy sources such as solar, wind…, co-generation, and energy recovery should be considered” (Lafayette College, n.d.). This commitment by the school effectively keeps the door open for the CHP conversation and is encouraging for future initiatives. Overall this policy puts CHP in a good place to move forward.

Lafayette College Methodology for Change

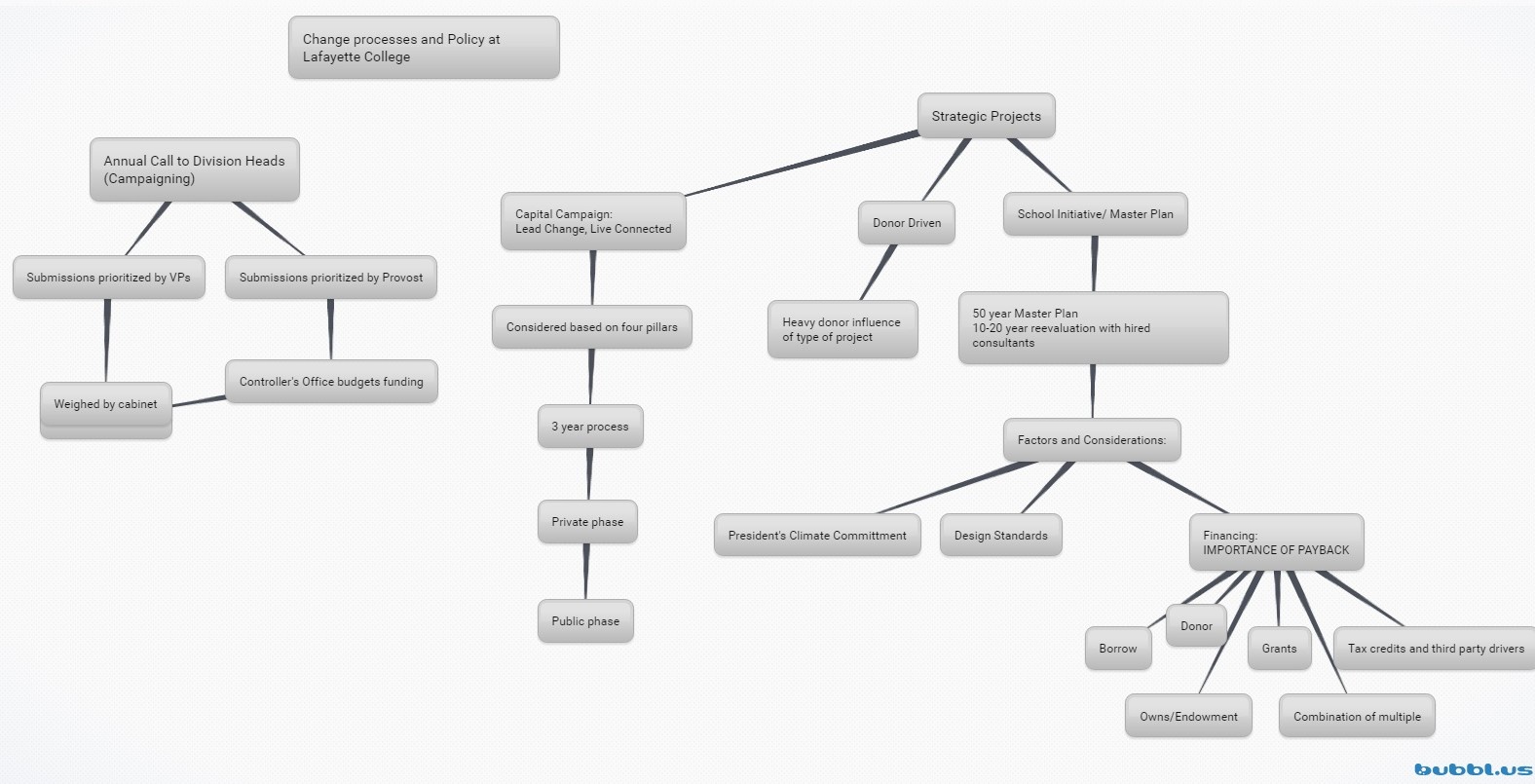

While Lafayette has a formal environmental policy is in place, it is necessary to evaluate Lafayette’s how change is decided at the College. Like all institutions of substantial size, Lafayette has a set process and line of policies that allow change and decision-making to be implemented through a streamlined and, ideally, bias-free system. We talked with Mary Wilford-Hunt, Director of Facilities Planning and Construction at Lafayette, to gain a better understanding of the decision-making process at Lafayette. She broke down the different ways infrastructural change is implemented at Lafayette and emphasized that one of the biggest determining factors was funding (M. Wilford-Hunt, personal communication, October 19, 2016). From this feedback, we constructed a diagram of the different pathways available to institute change (Appendix A). The left side branch, ‘Annual Call to Division Heads’, is not likely to be an option for CHP because the changes proposed are typically smaller and more specific to individual departments. CHP and other campus-wide, structural changes would most likely fall under the “Strategic Projects’ branch seen in figure 2. From there, the type of funding for the project drives which direction, of the three routes, would fit best. Again, considering the size of CHP and the respectively large initial investment costs, the project would most likely fall into a Master Plan path and be determined by funding available, as seen in the “Importance of Payback” block in Visual 2.

If the project was to be considered within the 50-Year Plan, there are revision periods throughout the term that edit and update the plan from a 10-20-year standpoint. In the past, Lafayette has hired consultants to evaluate the campus and develop a plan based on the college’s future goals. One of the core visions for Lafayette’s campus right now is expansion. While it is unlikely that the school’s main initiative would be solely environmental ‘greening’ of our campus’s facilities, other prioritized initiatives could help open the door to opportunities for ‘greening’, especially considering the President’s Climate Commitment. For further analysis of how the student body, faculty, and community organizations can strategically navigate CHP through this system, see the social context section of our report. However, from the results and decision-making end, key political stakeholders include members of the cabinet, in addition to anyone with a connection to funding. The heads of Plant Operations and Facilities Planning additionally hold some influence in the initiatives and implementation strategy.

Conclusion

Overall, the feasibility of CHP from a policy standpoint is dependent on actions from multiple spheres including federal, state, and institutional policy, incentivizing, and process regulation. As a result, there are stakeholders at each level of legislator: federal, state, and institutional. From environmental policymakers at the Capital, to natural gas regulations within the State of PA, as our communities of all scales move in one direction or the next in relation to support for CHP and green energy, the feasibility for a small price school, like Lafayette, to switch to CHP is equally effected. From there, the initiative will have a chance at becoming a reality, depending on how consistently CHP aligns with the future vision for the campus. As of now, while it would be helpful to have more developed federal and state policies to stabilize the natural gas fuel market and to encourage higher efficiency standards in the grand scheme of our feasibility analysis, the influence of these policies is a moderate disadvantage relative to the importance of key stakeholders at Lafayette. Within the Lafayette policy context, there are the energy policies and commitments in place that should support the installation of CHP.