Overview

If you work with Japanese picture postcards as historical source material, you have probably noticed that most surviving cards lack postmarks and other temporal indicators. This post provides a guide to estimating the age of these revealing artifacts, based on printing conventions that conformed to international and Japanese postal regulations. This post also provides several examples and explanations of Japanese postmarks.

Quick Guide

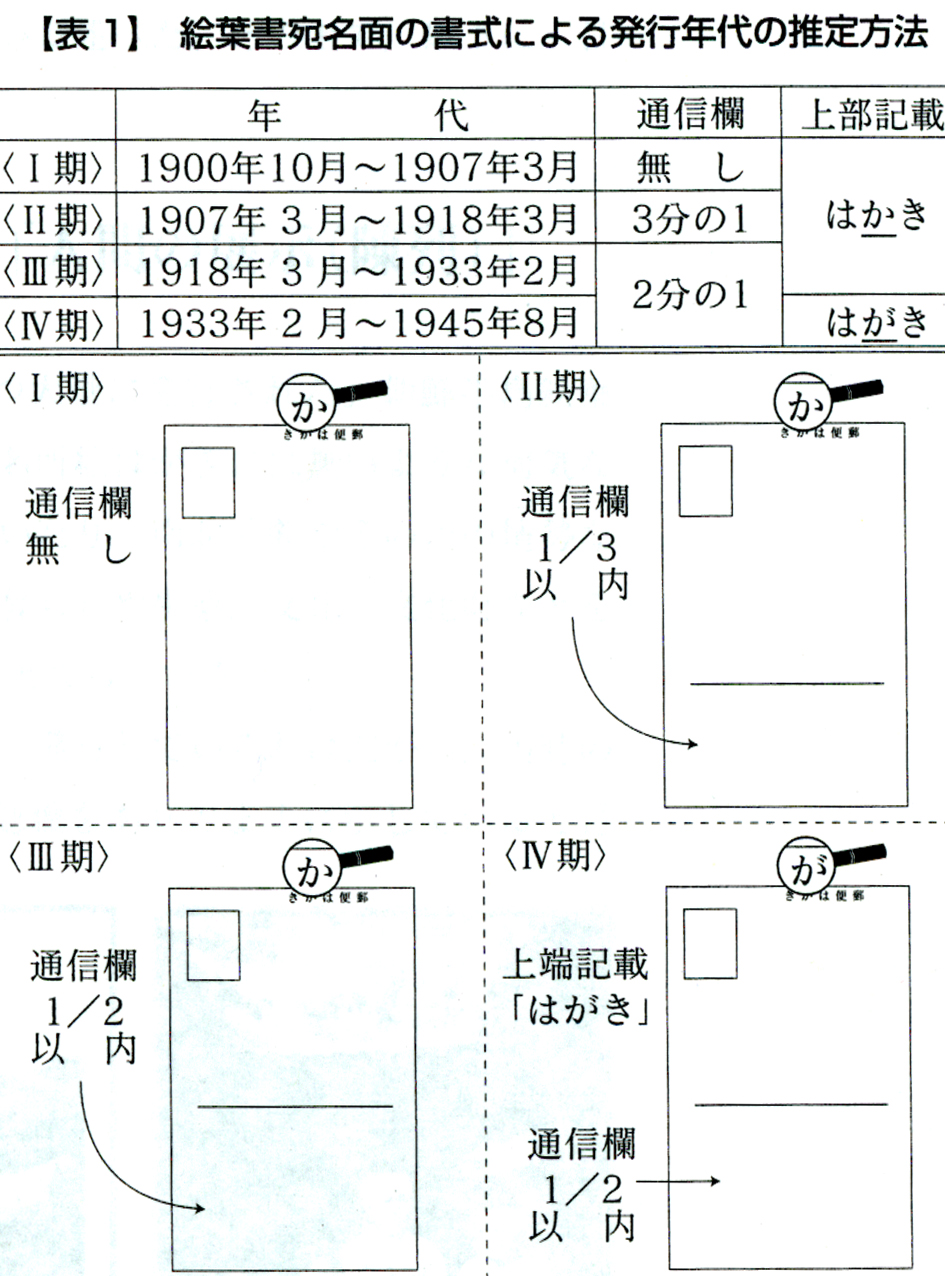

This chart by Urakawa Kazuya provides the basic method scholars use to subdivide Japanese picture postcards into four periods:

Period I. Undivided back: October 1900-March 1907

Period II. 1/3 divided back: March 1907-March 1918

Period III. 1/2 divided back: 郵便はかき: March 1918-February 1933

Period IV. 1/2 divided back: 郵便はがき: February 1933-August 1945

Urakawa Kazuya 浦川和也. “Kindai Nihonjin no Higashi Ajia, Nan’yō shotō e no ‘manazashi’: ehagaki no rekishiteki kachi no “ibunka” hyōshō” [The Japanese “Gaze” on the Peoples of East Asia and Micronesia: Archives Importance and the Other Race Representation, in the Japanese Picture Postcards]. Kokuritsu rekishi minzoku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku 140 (March 2008): 133.

Definitions

Japanese Picture Postcards (絵葉書)

“Ehagaki” (絵はがき・絵葉書) are mass-produced postcards designed primarily for the domestic Japanese market, in conformity with regulations issued by the Japanese postal service. Japanese Picture Postcards (絵葉書) could be (and were) sent abroad, because Japan was a signatory to the Universal Postal Union after 1877. However, postcards manufactured in Japan for the tourist trade, specifically to be mailed abroad, lack the Japanese-language term for postcard ( 郵便はがき) on the back. Although many export-market cards had the Chinese character phrase 萬國郵便聯合端書 [Universal Postal Union Postcard] printed on the back, these tourist-trade cards did not include the Japanese postal term 郵便はがき. Export-market cards are not considered “Japanese Picture Postcards” for the purposes of this guide, or in the scholarship upon which this guide draws.

The front side of a Japanese Picture Postcard features a printed photograph, drawing, or painting. Hand drawn or painted postcards, or “illustrated missives,” are known as “etegami” (絵手紙). Etegami are an important part of Japanese postal history and date back to the 1870s, but they are treated as a separate medium in Japanese-language postcard scholarship.

The back of a Japanese Picture Postcard was reserved for addresses from 1900 to 1907. After 1907, messages could be written on the back of postcards–on the other side of a dividing line from the address.

In Japanese-language historiography, picture-postcard history begins in 1900, with the appearance of mass produced, image-bearing cards stamped with the designation “郵便はがき.” Other types of illustrated postal cards, including etegami, New Year’s cards (年賀状・年賀はがき), and tourist-market cards, were produced and mailed well before 1900. But it was only after October, 1900, that private companies in Japan were allowed to print their own postcard stock in conformity with postal regulations for domestic mail. This change in regulations ushered in a new era of experimentation, commercial competition, design innovation, and circulation of mass-produced imagery within the Japanese empire (including Taiwan, and later Korea, Sakhalin, and the South Seas Islands).

Thank you very much to Paul Steier for bringing to my attention the many foreign-market, new year’s, and hand-illustrated postcards that were manufactured and mailed in and from Japan from the 1880s through 1900. Mr. Steier has made the historically correct point that Japanese Picture Postcards, as defined in this guide, are only a subset of illustrated postal cards that were made in Japan. If we expand the definition of picture postcards beyond that used in postcard scholarship–which is generally aimed at trying to understand movements in Japanese popular culture, mass media, art history, and state propaganda–we can find many wonderful examples of illustration, hand-colored lithographs, and other forms of graphic arts on pre-1900 postal cards produced in Japan.

Undivided Back

The back of the card lacks a dividing line to separate the message and the address.

1/3 Divided Back

The back is divided so that 1/3 of the space is reserved for a message, and 2/3 is reserved for the address.

1/2 Divided Back

The back is divided so that 1/2 of the space is reserved for a message, and 1/2 is reserved for the address.

East Asian Image Collection Periodization

Based on research into the postmarks and cards themselves, contemporary journalism, secondary scholarship, and some postcard websites, the EAIC has devised the following periodization scheme:

Period I. Undivided back: October 1, 1900-March 27th, 1907

Period II. 1/3 divided back: March 28, 1907-February 28, 1918

Period III. March 1st 1918-February 14, 1933:

1/2 divided back w/ 郵便はかき OR

1/2 divided back w/ 郵便ハガキ (note: the katakana usage changes the ka/ga rule)

Period IV. 1/2 divided back w/ 郵便はがき: February 15, 1933-August 15, 1945

Discussion and Illustrations

Period I:

On October 1st, 1900, it became legal in Japan for private companies and individuals to produce picture postcards that the Japanese postal authorities would accept and deliver at the postcard rate. Precise regulations were published regarding the size of the postcards, and the format.

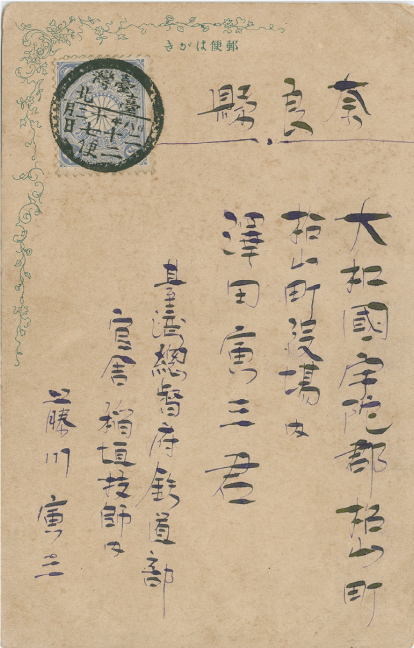

During this earliest period for picture postcards, the only information allowed on the back of the postcard was the addresses of the sender and and the recipient. Any messages needed to be written on the front, or picture side, of the card. Here is a postcard stamped with the date “December 27th, 1905.” It was sent from a Japanese colonial official in Taipei to Nara Prefecture. Notice that Japan is called “Yamato Kuni” here.

Here is the front of the postcard, which has both the picture and the message from the sender (this is a new year’s card for 1906).

Here is the front of the postcard, which has both the picture and the message from the sender (this is a new year’s card for 1906).

Here are some more examples of undivided back cards from Period I:

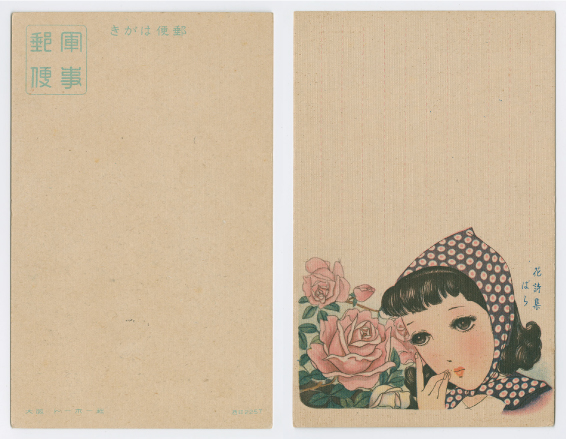

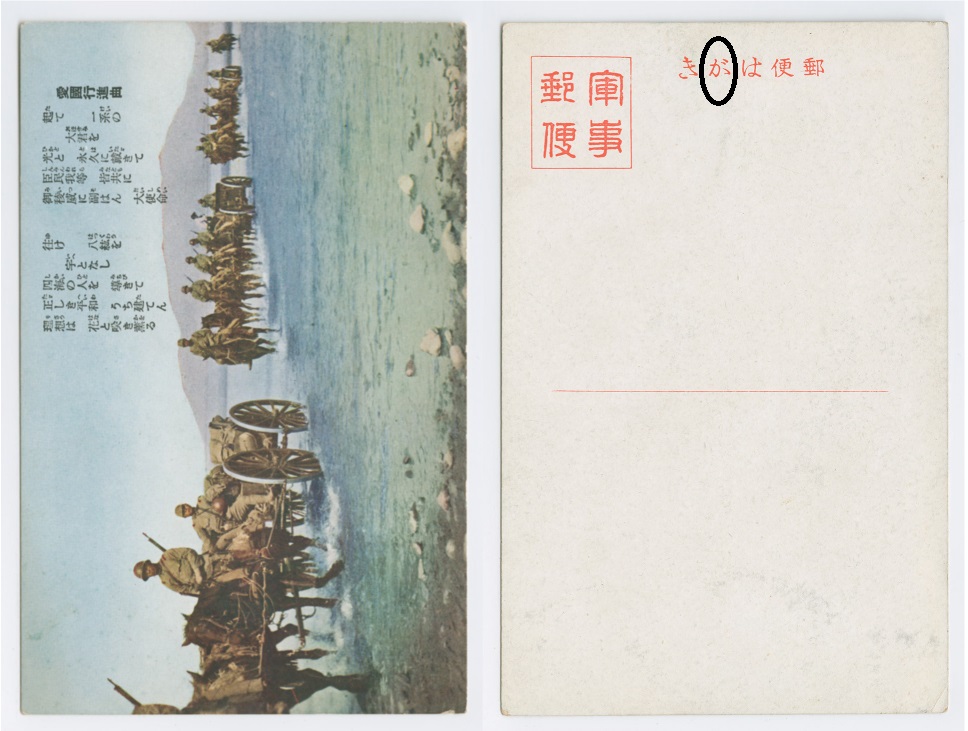

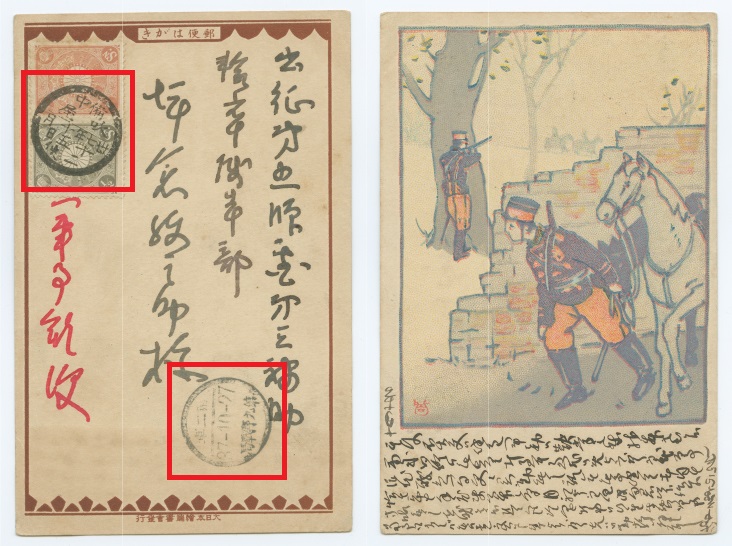

Some undivided back cards are military mail from the 1930s and 1940s. It should be clear from the type of cardstock, imagery, and other clues that such cards are not from Period I:

Some undivided back cards are military mail from the 1930s and 1940s. It should be clear from the type of cardstock, imagery, and other clues that such cards are not from Period I:

Period II.

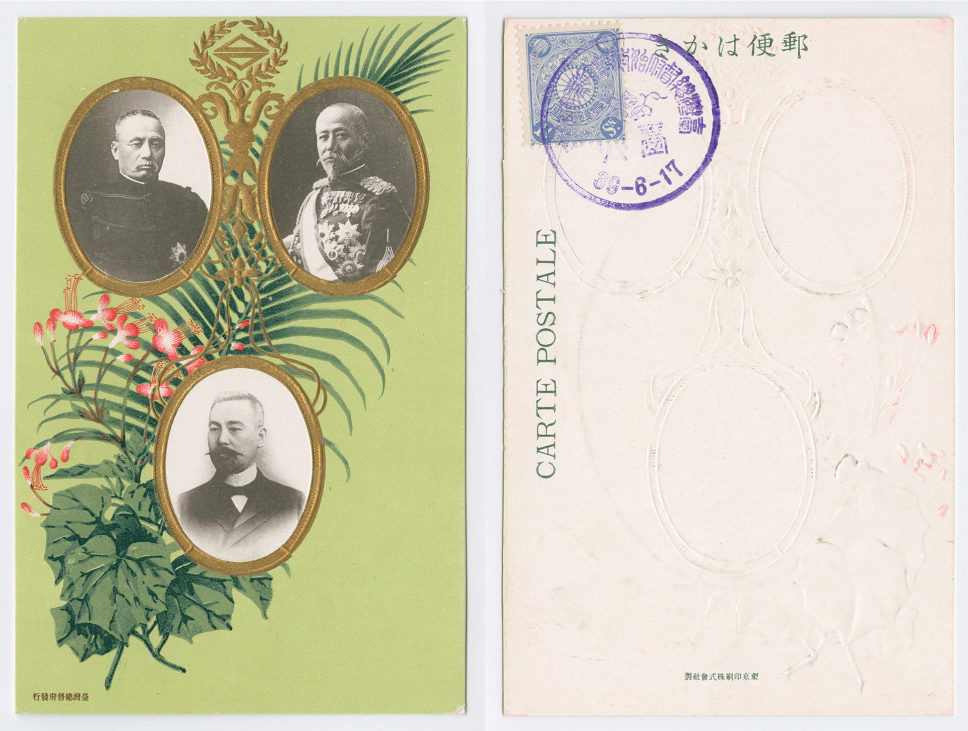

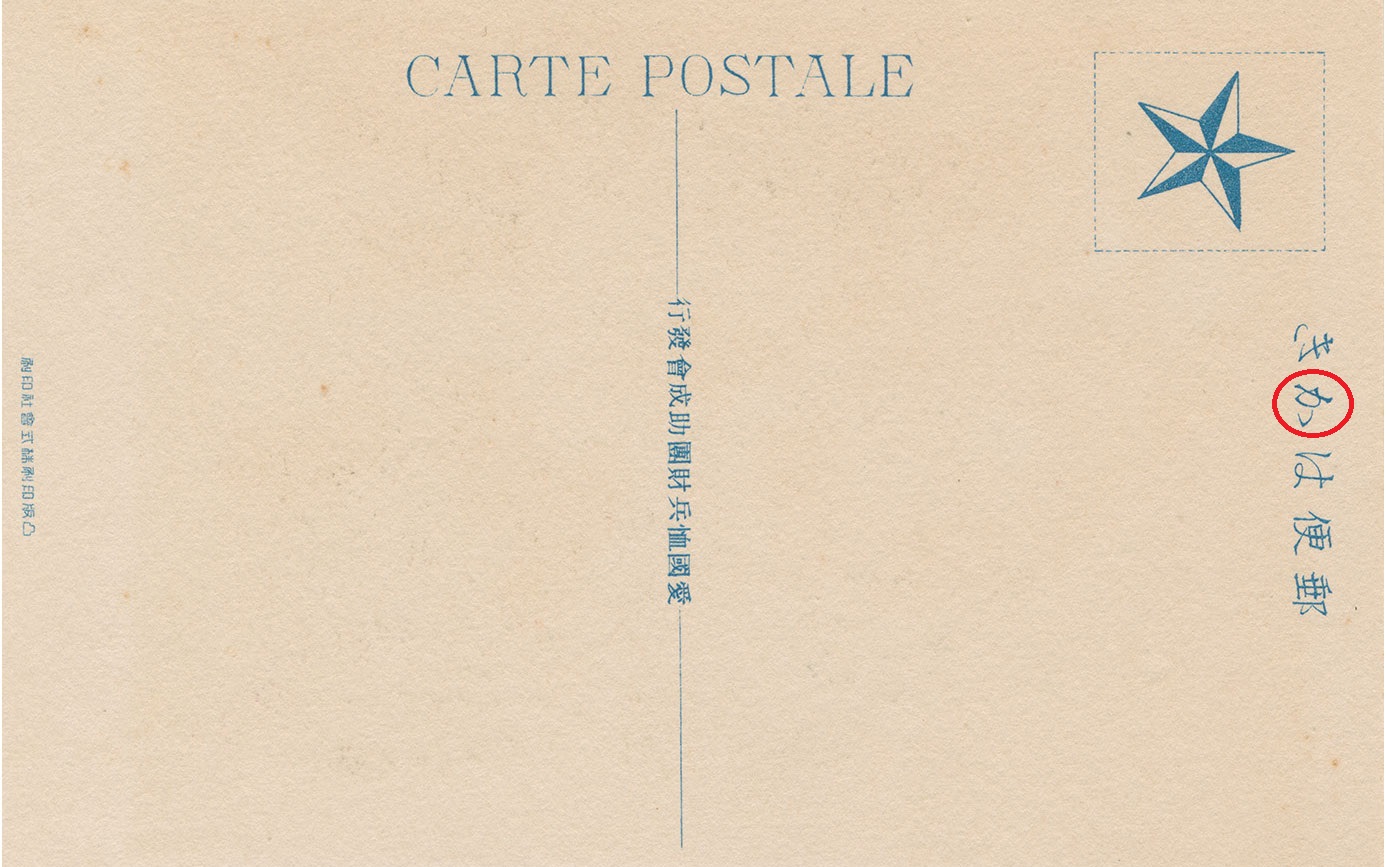

On March 27th, 1907, new postal regulations made it possible to use 1/3 of the back of a picture postcard for written messages. The card below was issued on June 17th, 1906, to commemorate the eleventh anniversary of the Taiwan Government General. Accordingly, its back is undivided, since this date falls into Period I.

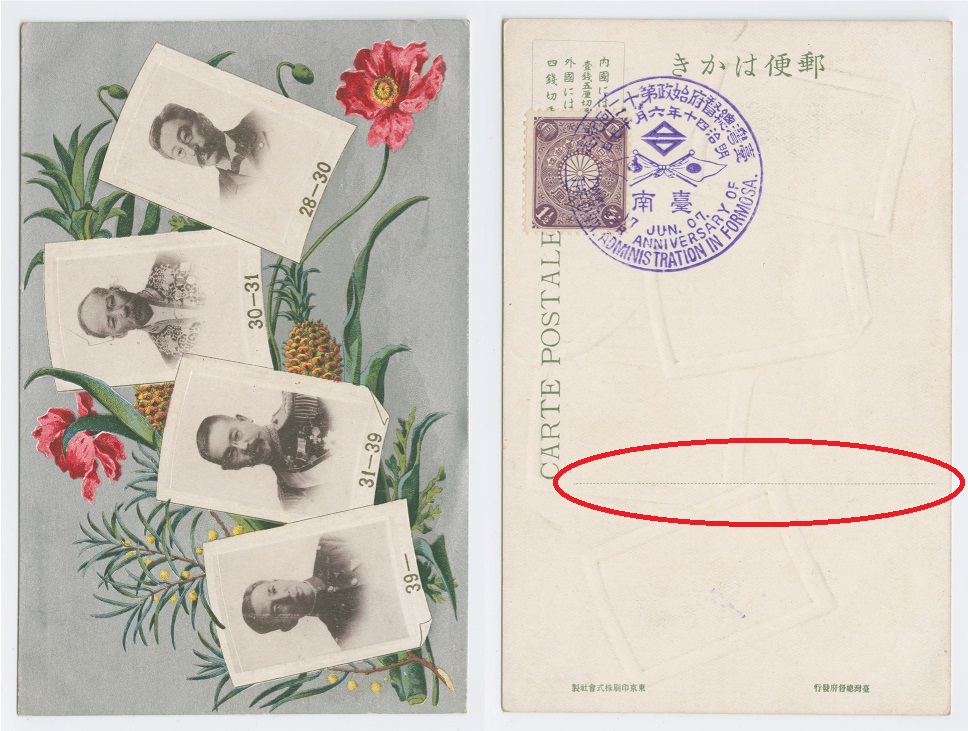

The next card was issued a year later to commemorate the twelfth anniversary of the Taiwan Government General, on June 17th, 1907. Since this date falls into Period II, the card has a 1/3 divided back:

The next card was issued a year later to commemorate the twelfth anniversary of the Taiwan Government General, on June 17th, 1907. Since this date falls into Period II, the card has a 1/3 divided back:

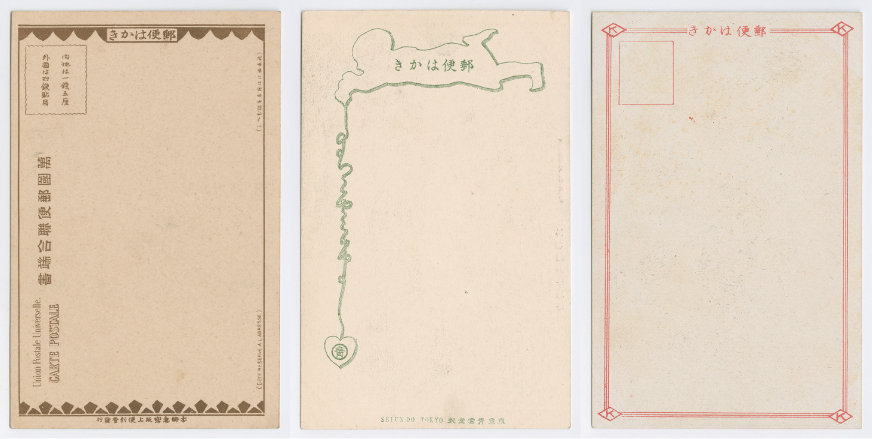

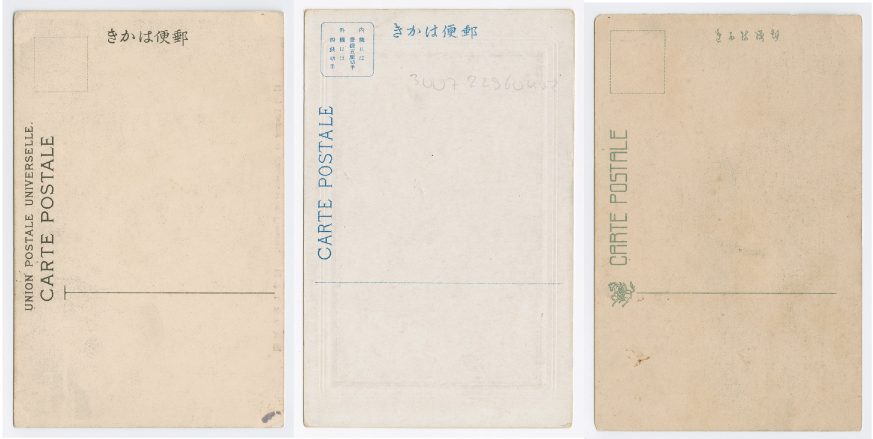

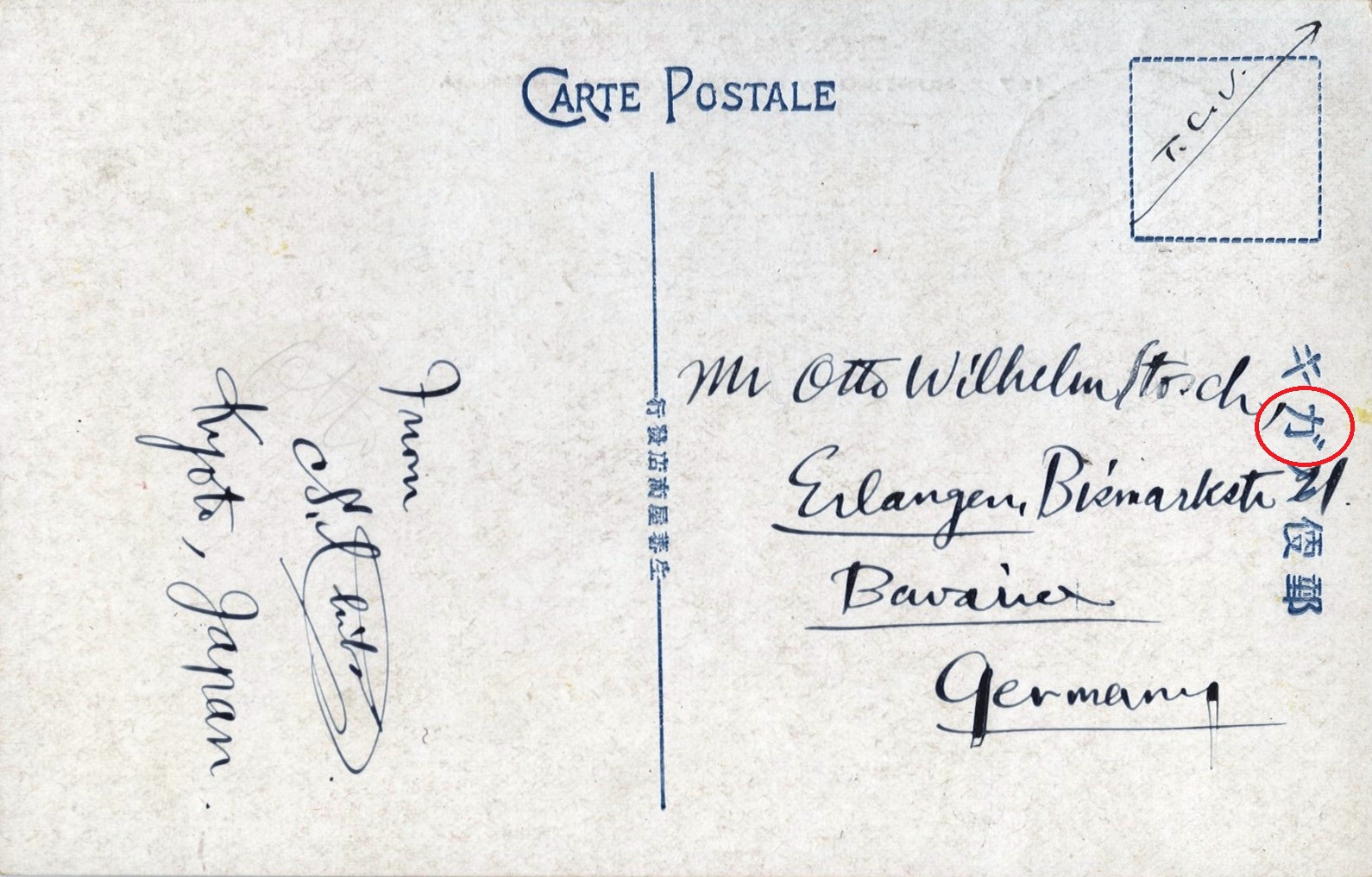

Here are some other examples of 1/3 divided back cards:

Here are some other examples of 1/3 divided back cards:

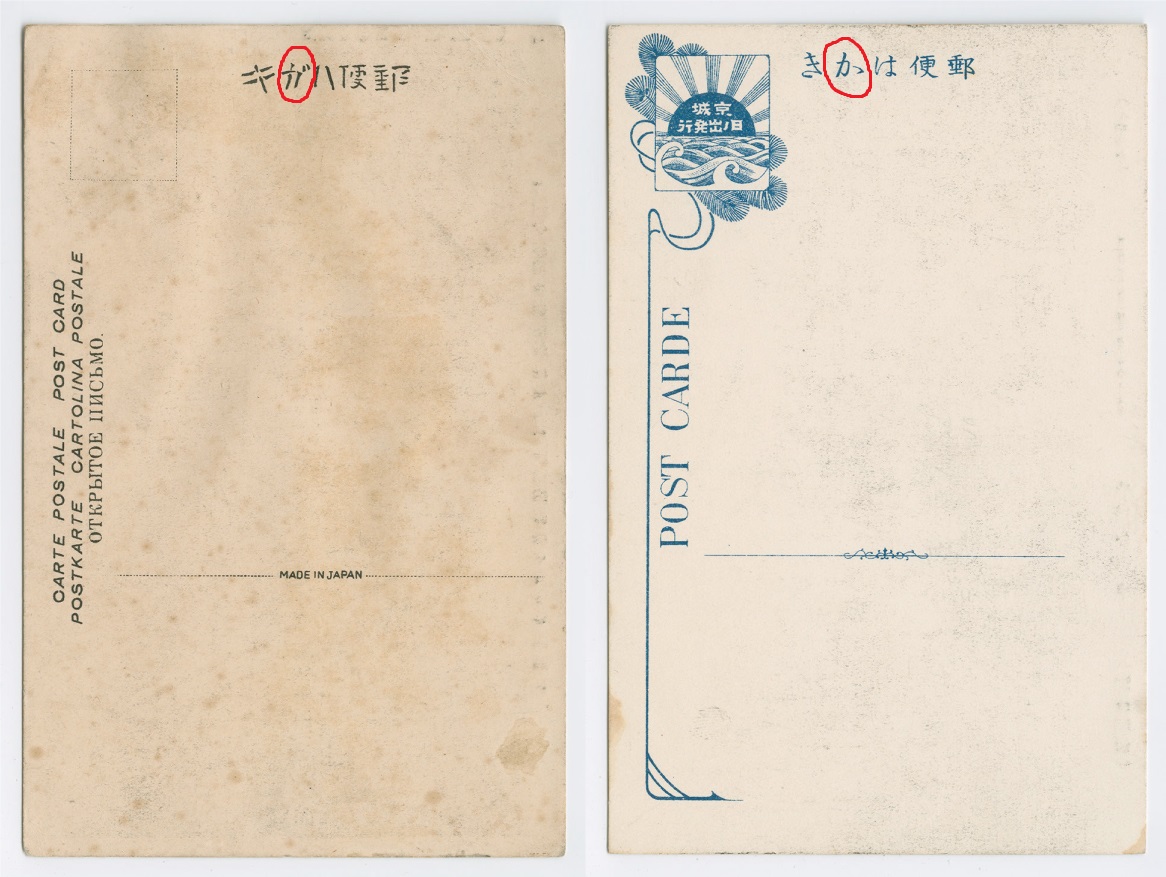

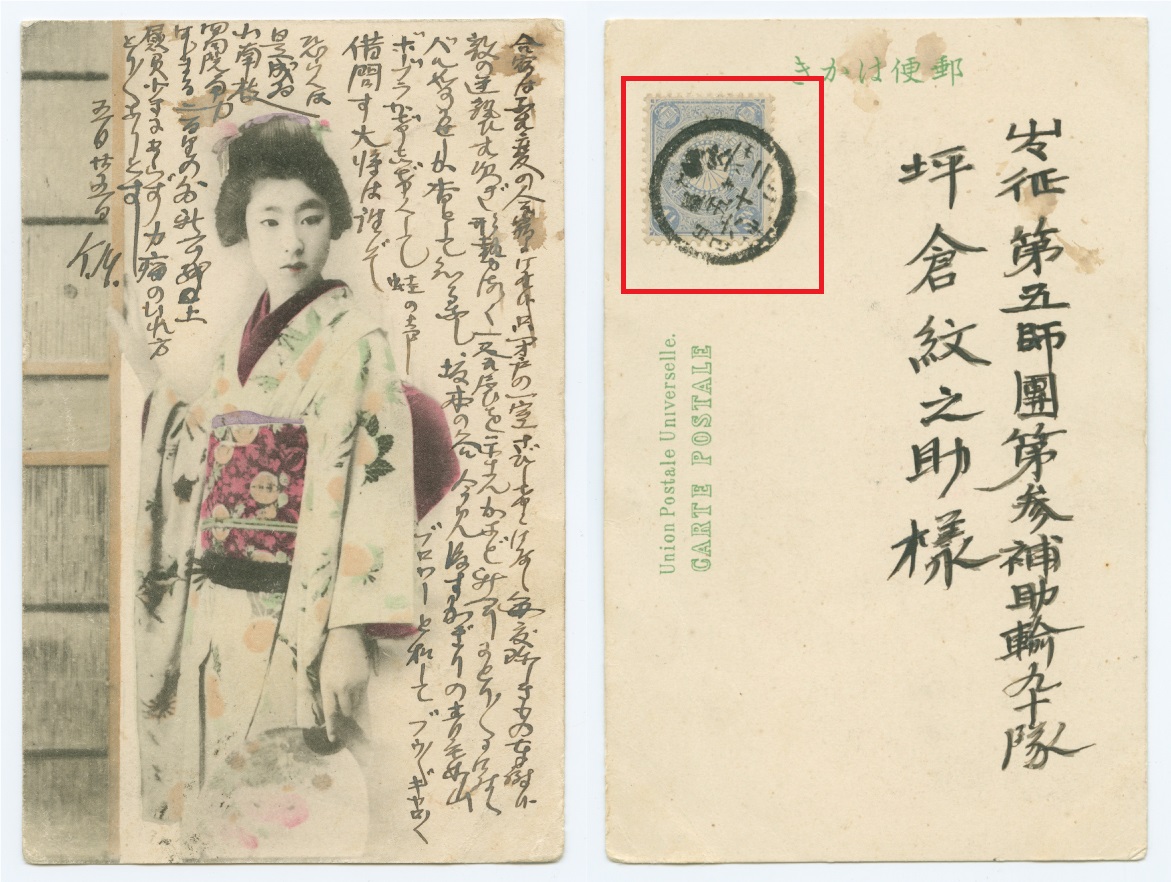

On all prewar (1900-1945) postcards, the phrase 郵便はがき is written from right-to-left, as きがは便郵. When hiragana was used, pre-1933 cards omitted the “ten-ten mark” that turns “ka” into “ga” (see card on right). When katakana was used, however, the “ten-ten” was retained (see card on left):

On all prewar (1900-1945) postcards, the phrase 郵便はがき is written from right-to-left, as きがは便郵. When hiragana was used, pre-1933 cards omitted the “ten-ten mark” that turns “ka” into “ga” (see card on right). When katakana was used, however, the “ten-ten” was retained (see card on left):

Period III.

From March 1st, 1918 through February 14th, 1933, Japanese picture postcards were printed with 1/2 divided backs, with the “ten-ten” in が (ga) omitted:

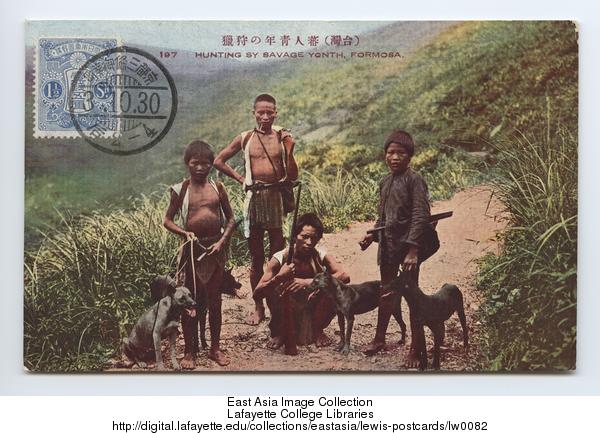

This next card retains the “ten-ten” in “ga.” Nonetheless, it falls into Period III because katakana is used to write out “hagaki.”

This next card retains the “ten-ten” in “ga.” Nonetheless, it falls into Period III because katakana is used to write out “hagaki.”

Because the front of this card is clearly postmarked “October 30, 1928,” we know it could not have been published in Period IV.

Because the front of this card is clearly postmarked “October 30, 1928,” we know it could not have been published in Period IV.

The EAIC contains 71 postcards with katakana “郵便ハガキ” printed on 1/2 divided backs. None of these cards are demonstrably post-1933. Many of them are indeed demonstrably from the 1918-1933 period. Based on this evidence, I classify 1/2 divided back cards that have “hagaki” written in katakana as Period III cards.

The EAIC contains 71 postcards with katakana “郵便ハガキ” printed on 1/2 divided backs. None of these cards are demonstrably post-1933. Many of them are indeed demonstrably from the 1918-1933 period. Based on this evidence, I classify 1/2 divided back cards that have “hagaki” written in katakana as Period III cards.

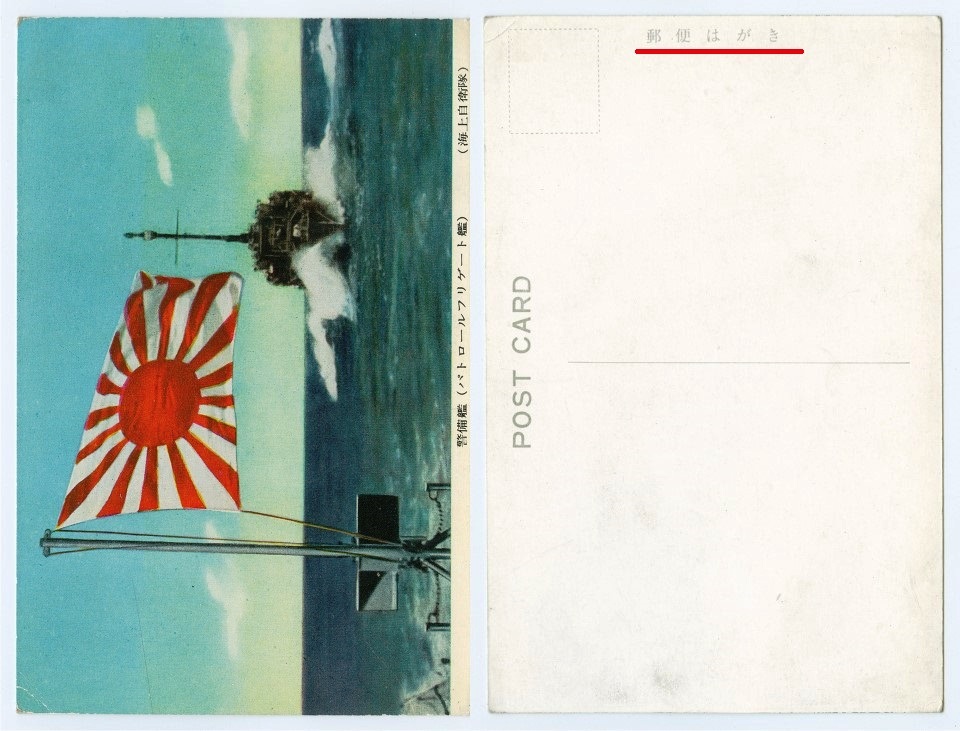

Period IV.

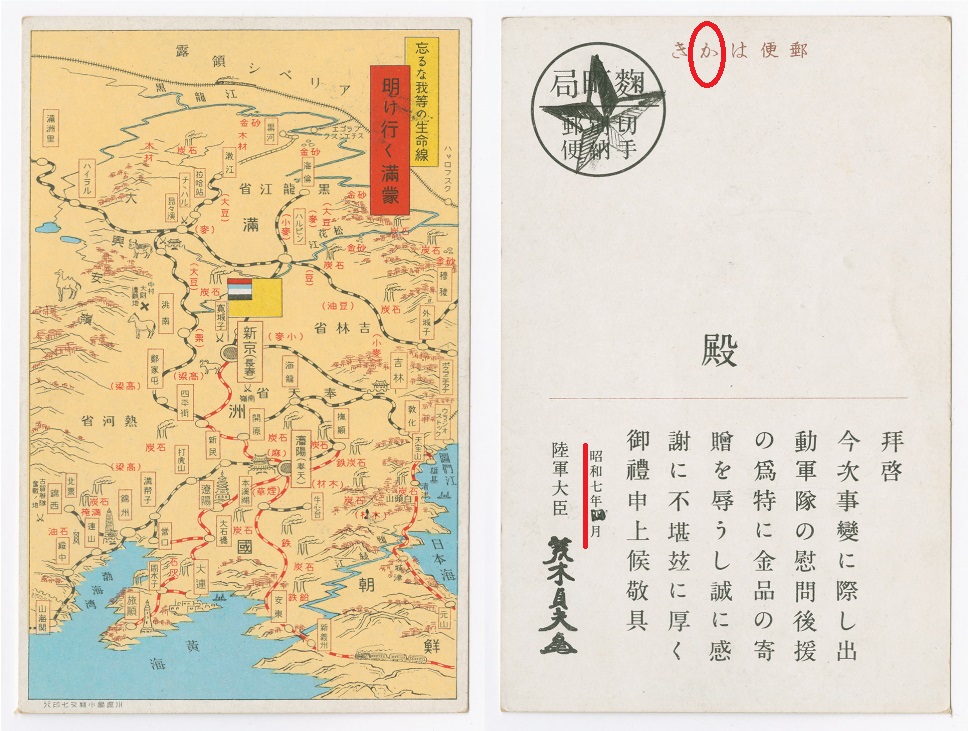

After February 15, 1933, the “ten-ten” was added to the “郵便はがき” marking on the backs of Japanese picture postcards. Here’s a postcard published in 1932, before the change in postcard printing conventions, but after the “Manchurian Incident”:

This postcard was published in or after February 1933, which is evident from the “ten-ten” on the kana for “ga” in “hagaki”:

This postcard was published in or after February 1933, which is evident from the “ten-ten” on the kana for “ga” in “hagaki”:

This “1/2 divided back, hagaki” style card was published until the end of the war (August, 1945)

This “1/2 divided back, hagaki” style card was published until the end of the war (August, 1945)

After the war, “きがは便郵” was reversed to read “郵便はがき” as shown in this next card from the American Occupation Period:

Exceptions

Some Japanese picture postcards from Periods III and IV do not have the standard 1/2 divided back “hagaki” mark. These exceptional cards are military mail, “real photo” postcards, and postcards produced for foreign consumption–as far as I can tell.

1926 Taipei Industrial Exposition Real Photo Postcard

1926 Taipei Industrial Exposition Real Photo Postcard

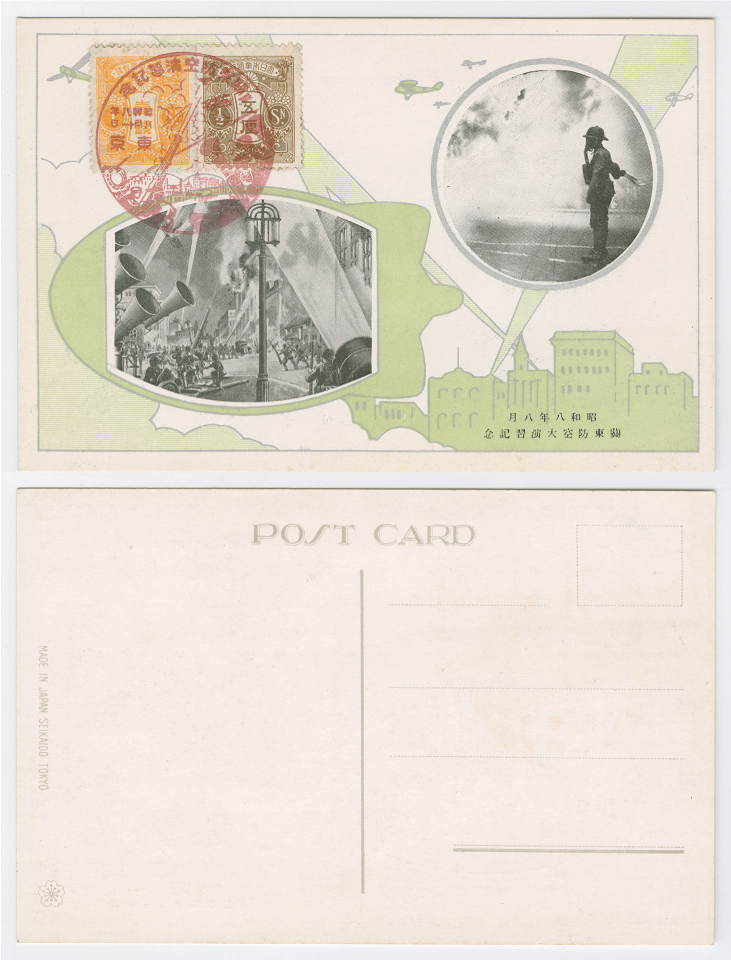

Commemorating an August 1933 Air Defense Drill

Commemorating an August 1933 Air Defense Drill

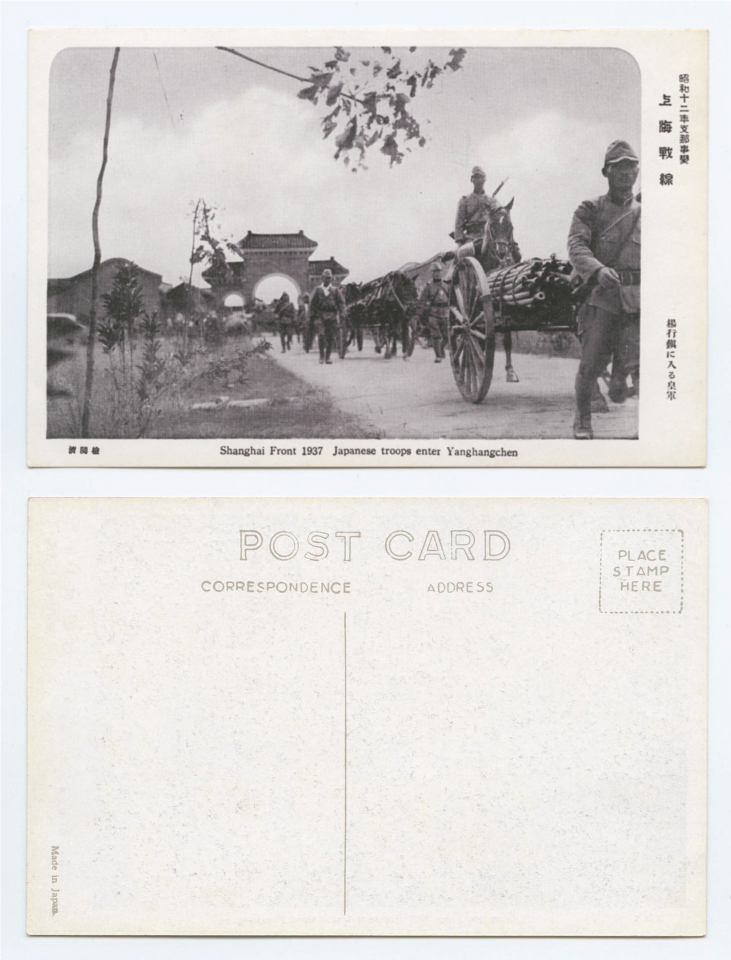

Commemorating invasion of Shanghai, 1937

Commemorating invasion of Shanghai, 1937

Manchukuo and China (郵政明信片)

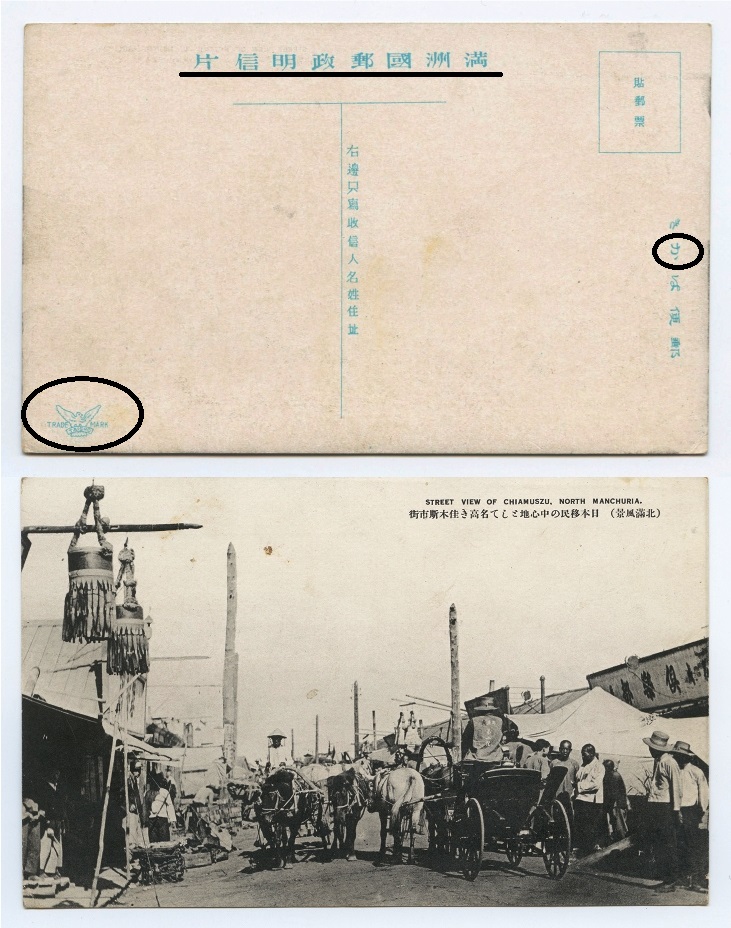

Manchukuo

Japanese picture postcards published for use in the postal systems of “Manchukuo” (1932-1945) and “The Chinese Republic” (1940-45) employed Chinese-language terms for “postcard” (明信片) and “post office” (郵政). Both countries were nominally sovereign and yet were governed by Japanese military and civilian officials. Thus, it is not surprising to find that each nation, no matter how “fake” in retrospect, possessed distinctive flags, postage stamps, currency, and postal regulations. I am still trying to work out a periodization scheme for these cards. What follows are some examples of Chinese-language markings on Japanese picture postcards.

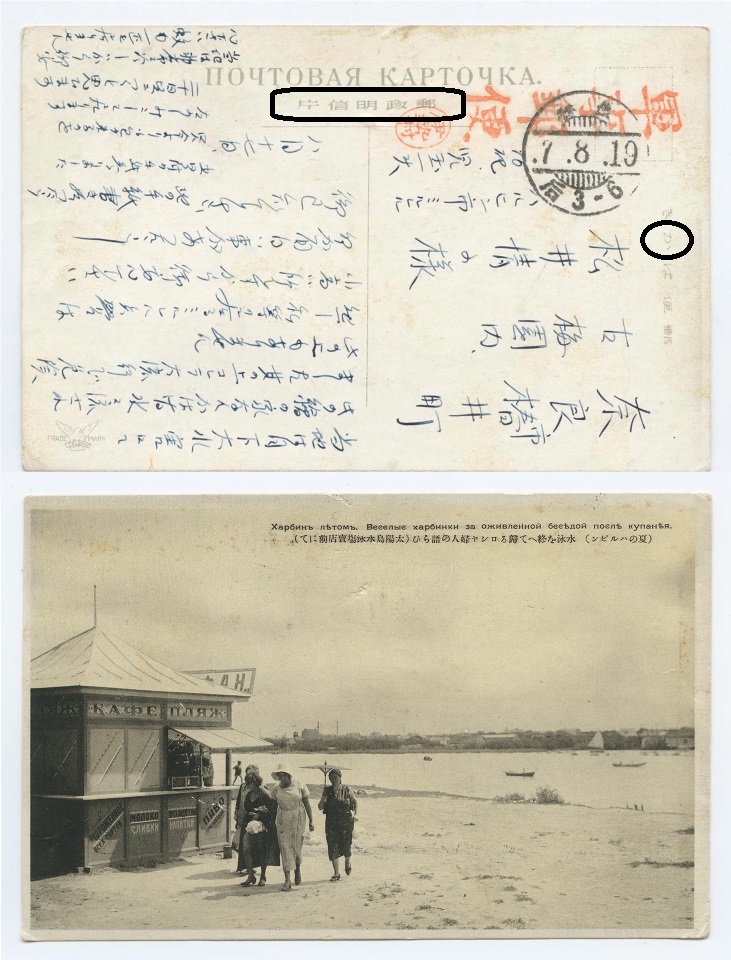

This first example is postmarked “August 19, 1932.” The lack of a “ten-ten” on the “ga” indicates that it was issued before February of 1933. The front depicts a scene from Harbin, which had a significant Russian population in the early 1930s. The front of the card is bilingual Russia-Japanese. The back says “postcard” in Russian, Chinese, and Japanese. It was mailed by military packet, as indicated by the red “軍事郵便” stamp. My guess is that this card was designed for sale to Russian and Chinese residents of Harbin, as well as Japanese soldiers, settlers, and officials. The back of the card suggests that it was intended for use in the postal systems of all three countries.

Here’s another card from the same period, but with “満洲國郵政明信片” “Manchukuo Postal Service Postcard.” The Chinese-language text on the back now includes instructions in the stamp box to affix a stamp, and instructions to reserve the right half of the postcard for the address (along the dividing line). The Japanese word “郵便はがき” is retained, and the card was produced by Taisho, a Wakayama Prefecture based company. So this is Japanese postcard that was produced, it would seem, for use in the Manchukuo postal service.

According to Shimada Kenzō’s guide to Japanese commemorative postcards, the Manchukuo Postal authority was established on March 9, 1932, under the administration of the Transportation section. On April 4th, the Manchukuo state seized control of Republican China’s Liaoning and Jilin postal bureaus, but the International Postal Union refused to recognize this gambit on April 24th, 1932. In July, the Nanjing government refused to handle Manchukuo postage, withdrew their postal workers, and cut off the northeast provinces. In response, the Manchukuo government took over all Chinese mail service, and began to issue its own regular stamps and postcards on August 1st, 1932 (Shimada 2009, p. 214). Daqing Yang notes that the Republican Government was unable to isolate Manchukuo in terms of international postage because the Japanese postal service could route mail through the Kwangtung Leased Territories (Yang 2010, p. 81).

The well illustrated and documented website “Manchukuo Stamps” provides examples of government issued postcard backs that resemble the card under discussion: these were first issued on 26 July 1932. Thus, it would seem that this card, and others like it, were issued between July 26, 1932, and February 14, 1933, since all seven examples that I’ve looked at have a か instead of a が for 郵便はがき.

On March 1st, 1934, Pu Yi was declared the “Kangde Emperor” and Manchukuo was recognized as an “Empire” by the Japanese government. The new postal service now appeared as 満洲帝國郵政 on government-issued “imprinted” postcards. The Manchukuo Stamps site shows this new imprint in effect by November 1st, 1934. Consistent with the new status of Manchukuo as an empire, the phrasing 満洲國郵政 should have fallen out of use after March 1, 1934. Tentatively, I would estimate the date of postcards with “満洲國郵政” on the backs as falling between July 26, 1932 and March 1st, 1934.

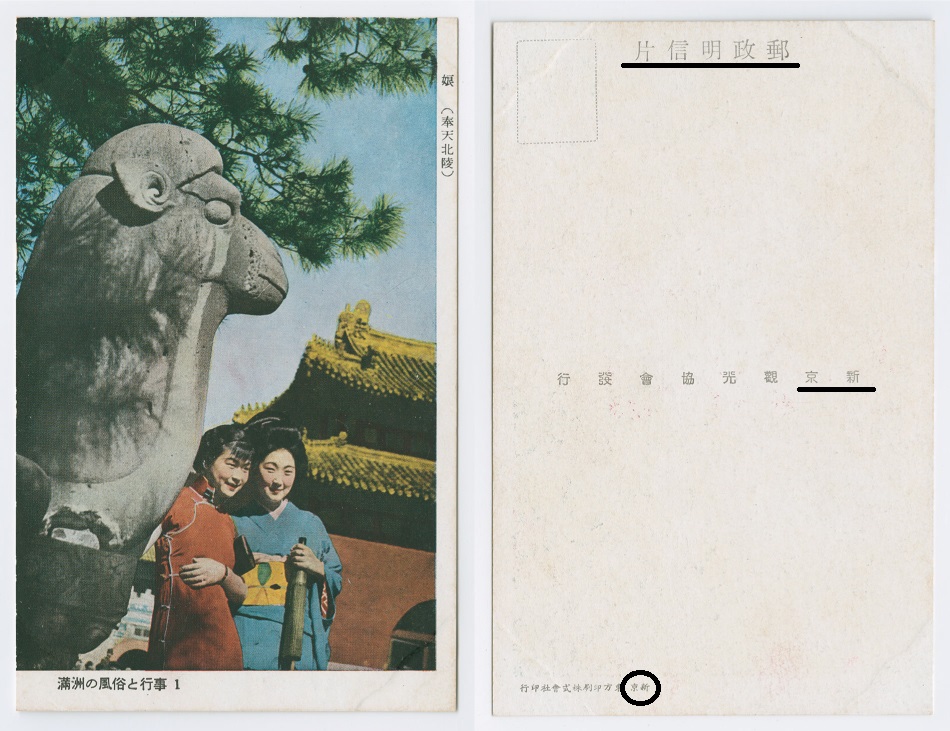

This next example is from Mukden/Shenyang at the Royal Tombs of the Manchu Emperors. There is no “郵便はがき” mark, but only “郵政明信片.” It was published by the “Shinkyo Tourist Society.” Shinkyo 新京 was Japan’s capital of Manchukuo (the city of Changchun).

This new generic Chinese word for postcard, without a trace of “Manchukuo,” was put on government-issue imprinted postcards from Manchukuo from January 1935 (Manchukuo Stamps). After the Republican government in Nanjing attempted blockade of Manchurian mail, the Japanese pressed for a renewal and strengthening of communication ties (Yang 2010, 99-100). An agreement was reached in December, 1934, to lift the ban an Manchukuo mail in Republican China. Thereafter, 郵政明信片 was used on Japanese official imprinted postcards from Manchukuo into the 1940s. Thus, I would tentatively date Japanese postcards with 郵政明信片 markings as dating from January, 1935 through the early 1940s (I do not know the end date).

It should be noted that the overwhelming majority of Japanese postcards with Manchurian themes retain the postal conventions outlined in the Periods III and IV section above (1/2 divided backs with 郵便えはがき marks in Japanese.

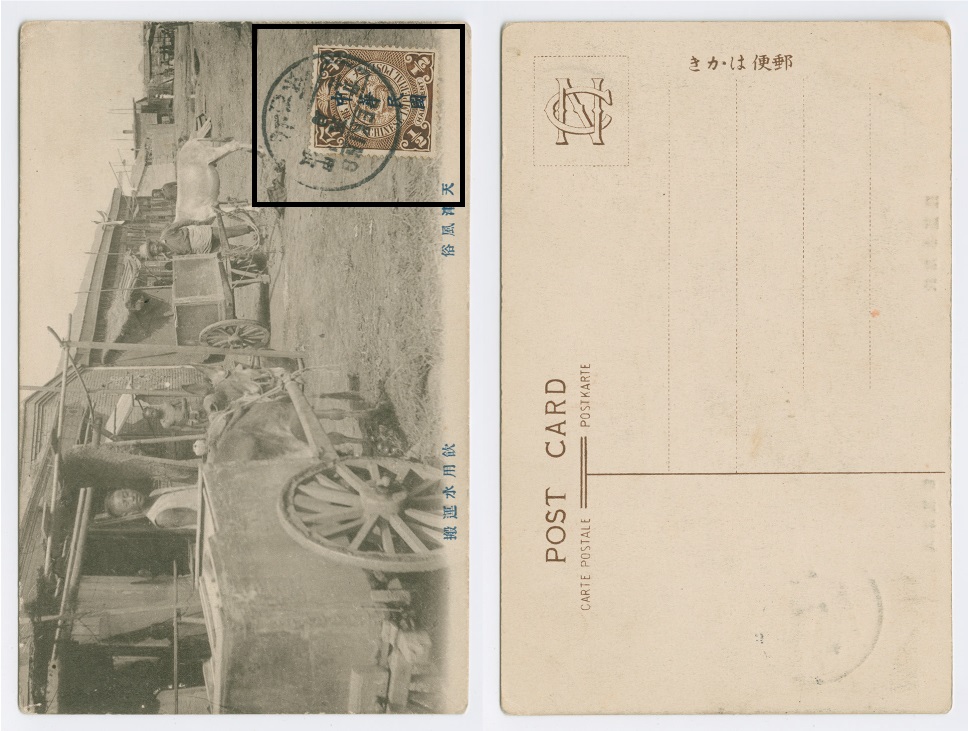

China

This next card is marked “Republic of China” 中華民國郵政. These are Japanese postcards designed for use in the Chinese postal system. This marking can be found on postcards dating as early as June 10, 1932, about six weeks after the Chinese Postal Bureau was unified under a single organ on May 1, 1932. Until I can find counter-examples, I assume cards marked like the one below were published after 05-01-1932.

There is a fascinating history of Sino-Japanese friction, diplomacy and intercultural relations to be disentangled with reference to these above mentioned postcard conventions. Kishi Toshihiko 貴志俊彦 has discussed these issues in his Manshūkoku no bijuaru-media: Postā, ehagaki, kitte 満洲国のビジュアル・メディア: ポスター・絵はがき・切手 (Colonial Manchuria’s visual media: Posters, pictorial postcards, postal stamps). I currently lack sufficient data to propose a periodization scheme for these types of cards.

There is a fascinating history of Sino-Japanese friction, diplomacy and intercultural relations to be disentangled with reference to these above mentioned postcard conventions. Kishi Toshihiko 貴志俊彦 has discussed these issues in his Manshūkoku no bijuaru-media: Postā, ehagaki, kitte 満洲国のビジュアル・メディア: ポスター・絵はがき・切手 (Colonial Manchuria’s visual media: Posters, pictorial postcards, postal stamps). I currently lack sufficient data to propose a periodization scheme for these types of cards.

Postmarks and Dates

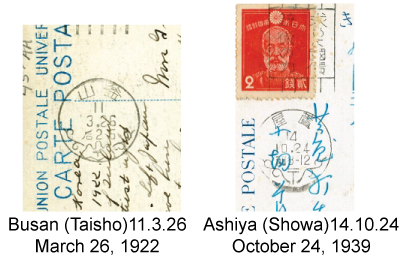

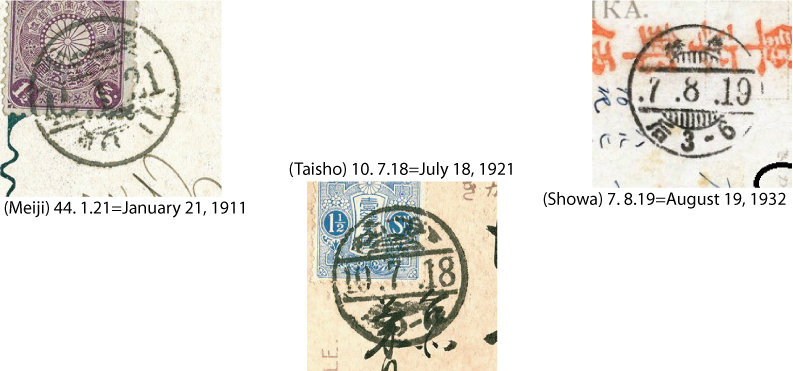

Japanese Calendar Postmarks

The most common postmarks on prewar Japanese picture postcards look like this:

The basic rule is: [Japanese Emperor Reign] Year-Month-Day.

The numbers represent reign years of the Japanese Emperors. These reign-year/Gregorian calendar conversions are relevant to prewar Japanese picture postcards (1900-1945):

Meiji Period=Year 33 (1900) through Year 45 (1912)

Taisho Period=Year 1 (1912) through Year 15 (1926)

Showa Period=Year 1 (1926) through Year 20 (1945)

Using the rules established in above section for Periods I-IV, it is usually clear which reign period a postcard falls into. For example, year “10” cannot be Meiji 10 (1877), because there were no picture postcards in 1877. If the postcard is Period III (1918-1933) [it has a “ka” instead of a “ga” in “hagaki”], then “10” means “Taisho 10” or 1921. However, if the card is Period IV (1933-1945), then it is “Showa 10” or 1935.

The number “7” in the year column would make a card either 1918 (Taisho 7) or 1932 (Showa 7), both of which fall into Period III. In general, postcards from 1918 and 1932 are sufficiently different in terms of lithographic technology, thematic emphasis, and other factors to make a determination possible.

“Machine Cancels”:

According to Manchukuo Stamps, the Japanese postal service began using this type of cancellation system around 1920.

According to Manchukuo Stamps, the Japanese postal service began using this type of cancellation system around 1920.

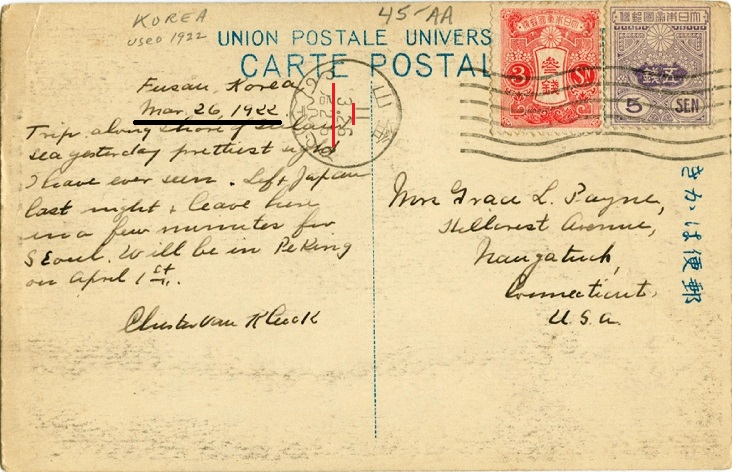

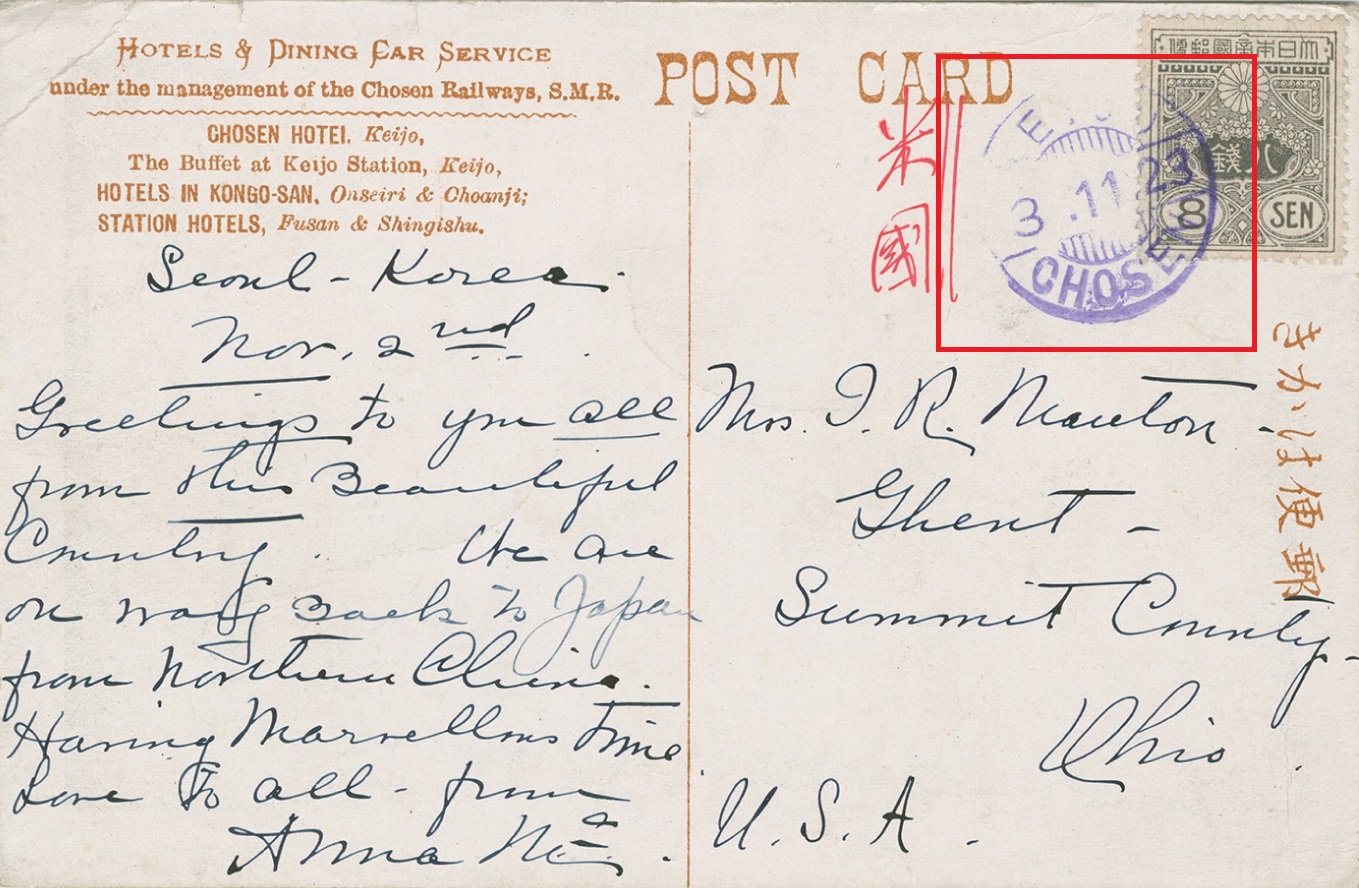

Gregorian Calendar Postmarks

Much less common are postmarks with Romanized place-names. The rule for these stamps is: Day-Month-[Gregorian Calender] Year.

On this card, “朝鮮” is written “CHOSEN.”

The written message is dated “Nov. 2,” so we can infer that the “3.11” refers to 3 November, and that the card is postmarked on November 3, 1923. This date is consistent with the Period III markings on the rest of the card.

The written message is dated “Nov. 2,” so we can infer that the “3.11” refers to 3 November, and that the card is postmarked on November 3, 1923. This date is consistent with the Period III markings on the rest of the card.

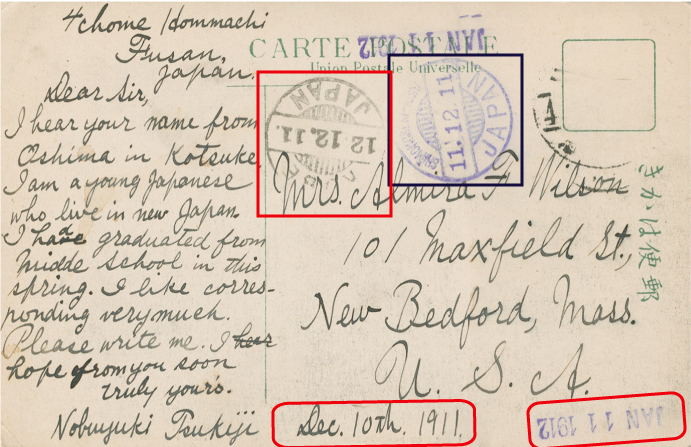

This card has two examples of romanized place-name postmarks:

Following the rules outlined above, we ascertain that the letter was signed by a letter-writer named Nobuyuki in Busan [“Fusan”], Korea on December 10th, 1911. The card arrived in Shimonoseki, Japan on December 11th, and in Kobe, Japan on December 12th, and probably landed in New Bedford, MA, USA on January 11th, 1912. The faint mark of “Meiji 44” is visible in the postmark near the stamps box, revealing that a “normal” postmark was also affixed to this postcard simultaneously with these more “foreign” styles.

Following the rules outlined above, we ascertain that the letter was signed by a letter-writer named Nobuyuki in Busan [“Fusan”], Korea on December 10th, 1911. The card arrived in Shimonoseki, Japan on December 11th, and in Kobe, Japan on December 12th, and probably landed in New Bedford, MA, USA on January 11th, 1912. The faint mark of “Meiji 44” is visible in the postmark near the stamps box, revealing that a “normal” postmark was also affixed to this postcard simultaneously with these more “foreign” styles.

Japanese Calendar with Sino-Japanese Numerals

During the first decade of the twentieth century, some Japanese postmarks took this form:

Sometimes, these were the only postmarks on the card:

Sometimes, these were the only postmarks on the card:

Other cards have both types of postmarks. On the card below, the Sino-Japanese numeral postmark was stamped twelve days earlier than the Hindu-Arabic numeral postmark.

Other cards have both types of postmarks. On the card below, the Sino-Japanese numeral postmark was stamped twelve days earlier than the Hindu-Arabic numeral postmark.

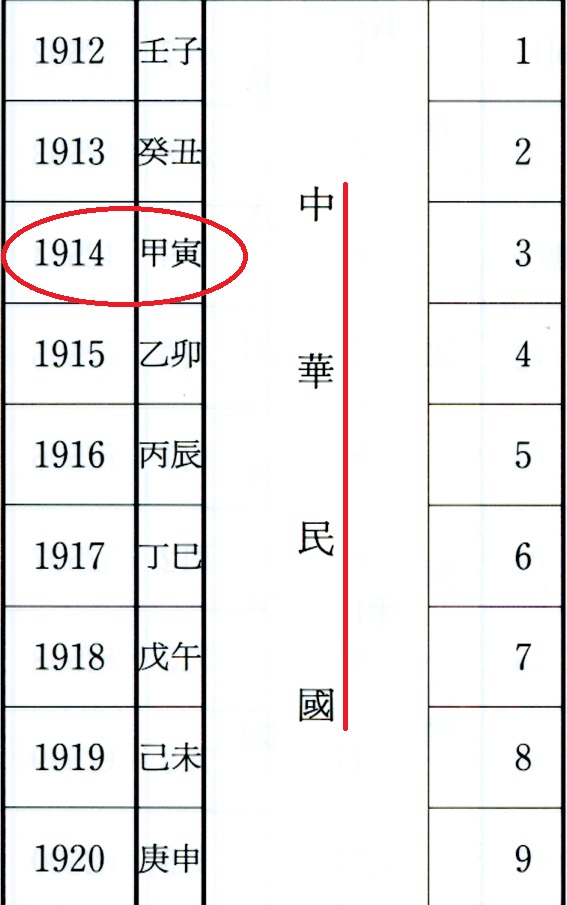

Sexegenary (60-year cycle) Years

Sexegenary (60-year cycle) Years

Lastly, Japanese postcards passing through the Republic of China (中華民國) postal system were sometimes marked with sixty-year cycle years. The following card was postmarked in on May 26th, 1914:

Here’s the “Republic of China” postmark (中華民國)

Here’s the “Republic of China” postmark (中華民國)

The date portion of the postmark reads: 甲寅 (blue) 五月(red) 廿六 (yellow)

The year “甲寅” is a 干支 or “Stem-Branch” or “sexegenary-cycle” year name, which has a very ancient pedigree in China, Japan, Korea and other places. This chart assigns Gregorian Calendar years to “stem-branch” years:

Conclusions

The above guide is subject to revision as more data becomes available and my research efforts deepen. As far as I know, there is nothing controversial about the dating methods proposed in the foregoing. This research is made possible by Eric Luhrs, James Griffin III, and Paul Miller at Lafayette College Digital Scholarship Services. This team has been designing software, capturing images, producing pdf files, and otherwise putting thousands of images at my fingertips, making it possible to connect these various types of evidence in a meaningful way.

Sino-Japanese Calendars and Dating Systems:

For an accessible but thorough introduction to reign years and the stem-branch cycle, I recommend this blog post by “Kristen D.”

http://www.tofugu.com/2014/07/15/understanding-the-ways-that-japan-tells-time/

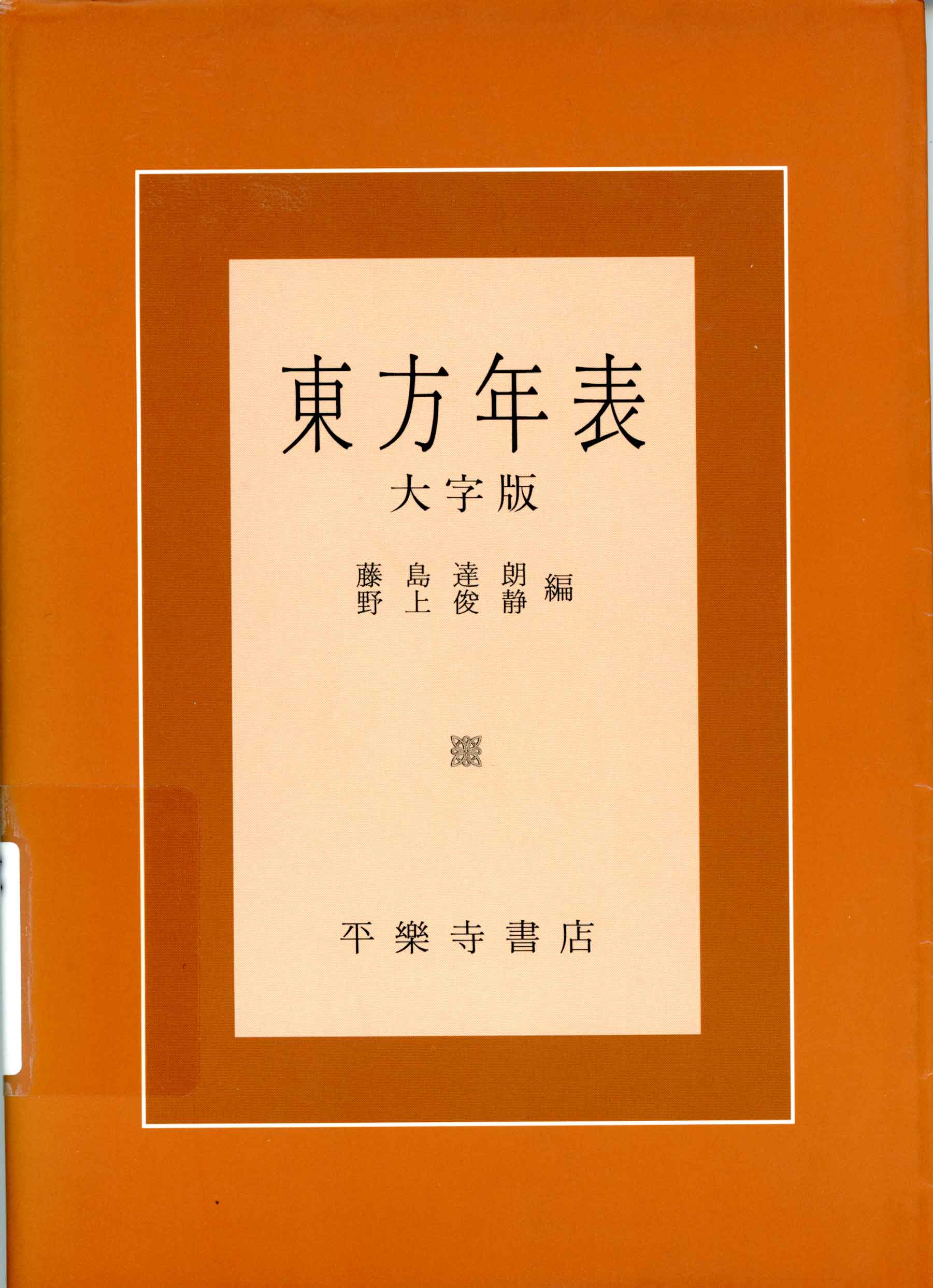

For a comprehensive set of tables to align the Korean, Japanese, and Chinese calendars with the Gregorian Calendar, back to ancient times, the following is indispensable for scholars who wish to date artifacts in East Asian History:

I have fun with, cause I found exactly what I used to be looking

for. You have ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have

a great day. Bye

Thank you for the history. I have a collection of 36 Japanese postcards that I think is in period 1/3 divide back. Also on the back are 2 circles for stamp placement. I think they are woodblock prints or lithos, I don’t know how to tell. May I send you a picture of a couple of them for your help? Feel free to send me an email.

I have noticed you don’t monetize lafayette.edu, don’t waste

your traffic, you can earn extra bucks every month with new

monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all sites), for

more info simply search in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools

Perhaps you can help me. I have a nice, though small, collection of 1930-1945 Japanese postcards, military, civilian, advertising, etc. I know nothing about them. Is there some sort of catalogue in English, ideally with a relative value scale? Much obliged.

The lack of postmarks on Japanese postcards has always been a bit of a mystery to me when using them as historical sources. This guide offering printing conventions as age indicators is a game-changer.

Thank You. Good for me.

Trying to find out about some old hand painted Japanese postcards and if I am possibly right and from what I saw on your blog post… they maybe Period 2… hope to hear from someone…

Thank you so much for this very useful resource. Hugely appreciated. We have referred to it many times

I always feel so much better after a session at 오피.

오피 seems to be everywhere lately; what’s your take on its popularity?

Discovering new websites is so much fun with 주소모음 at my fingertips.

주소나라 makes it so easy to keep track of all the websites I love visiting regularly.

알림톡 has simplified my life by streamlining my notifications.

The atmosphere at 오피 is so calming and peaceful.

If you’re looking for a reliable massage site, 오피가이드 is the go-to.

I just discovered this amazing 오피 that offers such relaxing massage sessions!