Herbert Bix’s much discussed Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2000) and the Hollywood film Emperor (2012) provide two examples of how middle-brow America has continued to put the Showa Emperor (Hirohito) at the center of events in World War Two, despite decades of revisionist scholarship that has sought to either demote him to a constitutional monarch, or broaden the base of explanatory devices for understanding Japanese wartime ideology and mobilization.

In Bix’s account, based on decades of research in Japanese-language source material, the Emperor was an active military planner and eager participant in the war. In the cinematic treatment of Japan’s “surrender,” Emperor, Japan is said to have a “2000-year old” culture that is deeply efficacious, homogenous, and pivots around the imperial line. This imperial culture, intones a “native informant” played by Nishida Toshiyuki as “General Kajima,” enabled “the Japanese” to display an unwavering sense of duty, while losing their humanity, over the course of the war.

In a well researched analysis of official visual propaganda, which includes postcards held in the East Asia Image Collection as source material, David C. Earhart has marshaled an impressive array evidence to also lend support to an emperor-centered view of the war. In his Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 2008), Earhart writes:

[The Emperor] was a central force in a sacralized nation. The war was authorized in the name of the Emperor, as the highest authority in the land, and it was animated and consecrated by him as the highest priest of State Shinto. The “Incident” in China was a “Holy War” because the emperor decreed it so. As the divinized Japanese nation was waging war, State Shinto was locked in battle against the evil forces that damaged Japan’s national prestige and hindered the Japanese version of manifest destiny that placed Japan–the Land of the Gods–above all other nations and made the Japanese race supreme (p. 33).

Earhart demonstrates that images of the Emperor himself were relatively scarce in official propaganda. Instead, an implicitly emperor-centered aesthetic–based on a belief in Japanese exceptionalism–made its war propaganda distinctive. According to Earhart:

In boosting morale, the Japanese wartime media drew upon Japanese traditions: politics, history, society, culture. The [Civil Information Bureau]’s selectivity, its determination about what to show (and what not to show) to the people, reflects the Japanese government’s framing of social and aesthetic values projected as the nation’s unique tradition. Individualism, selfishness, and decadence–diseases spread by the West–were Japan’s sworn enemies in the “ideological war.” Self-sacrifice, propriety, and adherence to group norms were the cure, and in countless articles, the government … explained and illustrated the virtues of obedience, sincerity, a perfect physique, and spiritual purity (p. 9).

In this post, I will examine emperor-centered wartime ideology and its alternatives though the lens of wartime picture postcards. I begin with an observation that accords with Earhart’s findings: depictions of the Showa Emperor himself are uncommon in Japanese wartime propaganda. This is not because the image of his person was sacrosanct. There are many picture postcards of Hirohito as Crown Prince, and as a young emperor, before the “China Incident” of 1937. The following cards even emphasize his military function as “commander in chief.”

[ip0575] [Crown Prince Hirohito]

[ip0576] [Crown Prince on Military Inspection]

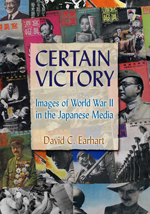

“Naval Boat Mikasa and Image of Admiral Togo and Prince Hirohito,” Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards, #2002.15738

“Naval Boat Mikasa and Image of Admiral Togo and Prince Hirohito,” Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards, #2002.15738

In 1929, the year after his coronation, the Showa Emperor was depicted as a military commander in this postcard.

[ip0222] [Showa Emperor and Battleships]

This card, which also appears to be from the 1920s, uses the same photograph to commemorate a military review as well, though it is not clear which review:

“昭和天皇 Showa Emperor, Commemorating a Military Review” From Sapporo Municipal Central Library Digital Archives (#0500-03-21-01)

“昭和天皇 Showa Emperor, Commemorating a Military Review” From Sapporo Municipal Central Library Digital Archives (#0500-03-21-01)

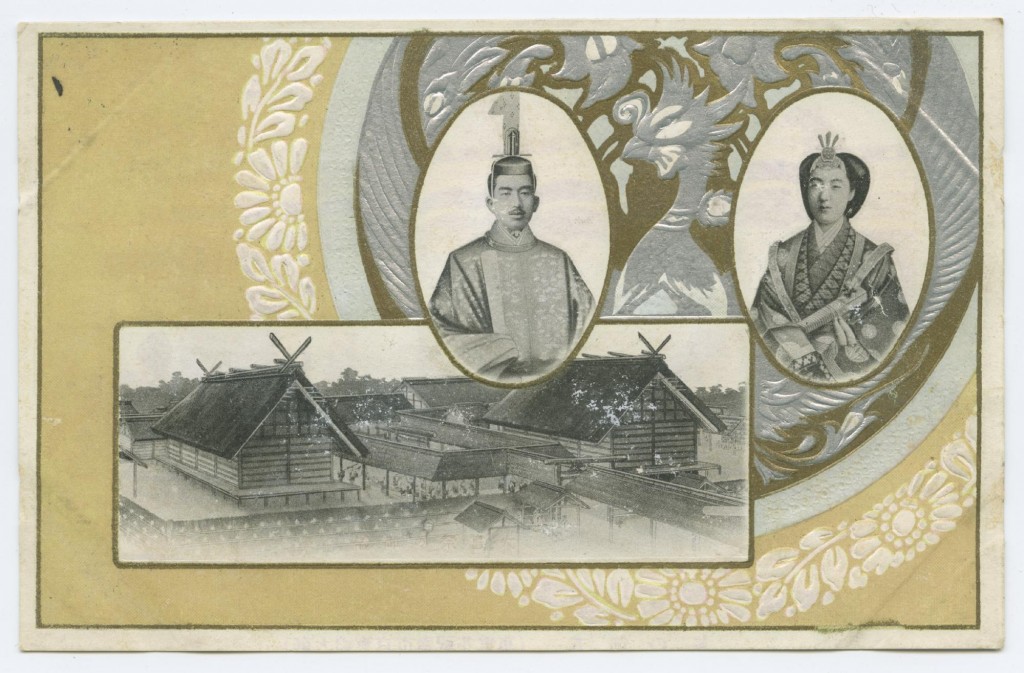

More typically, postcards of Hirohito were less explicitly militaristic, like this item commemorating the Showa Emperor’s coronation ceremony (1928). Notice that this card uses the same photograph as the previous two “commander-in-chief” photos.

[ip0586] His Present Majesty’s Accession Ceremony

[ip0586] His Present Majesty’s Accession Ceremony

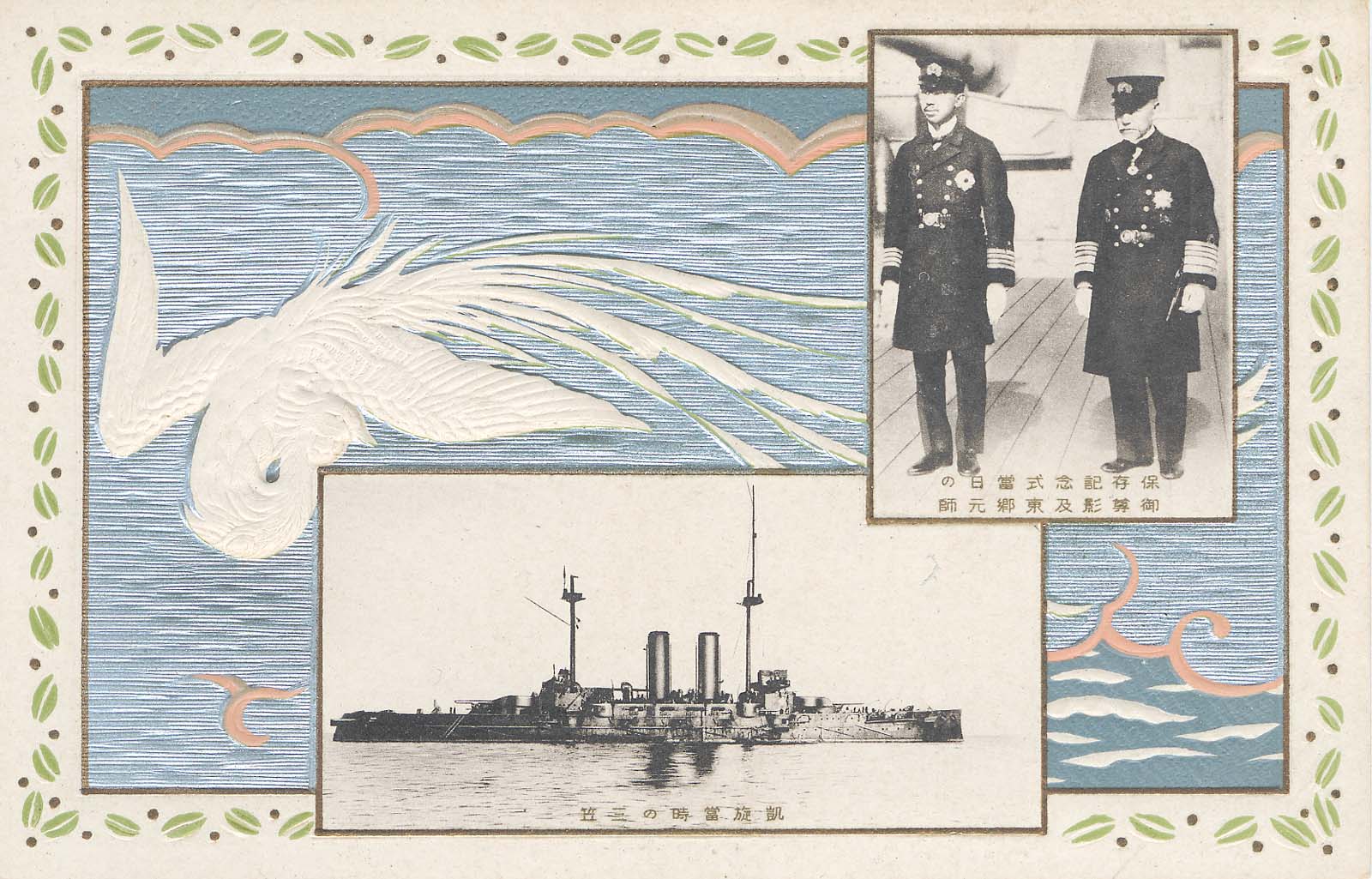

Here’s an image of the Emperor in late 1936, on the eve of the “China Incident,” at the Sapporo National Shrine. In this photo Hirohito does not don the clothes of a priest, but looks very much the part of a military officer:

“天皇陛下官幣大社札幌神社御参拝(昭和十一年十月七日)” Sapporo Municipal Central Library Digital Archives #0206-02-013-01

“天皇陛下官幣大社札幌神社御参拝(昭和十一年十月七日)” Sapporo Municipal Central Library Digital Archives #0206-02-013-01

But after Japanese ground forces had spread across north and central China in August of 1937, it seems that images of the emperor as a military man disappear from the picture-postcard record. Or at least I have not been able to locate wartime portraits of Hirohito that link him to Japan’s “Holy War” against China, America and the European imperial powers.

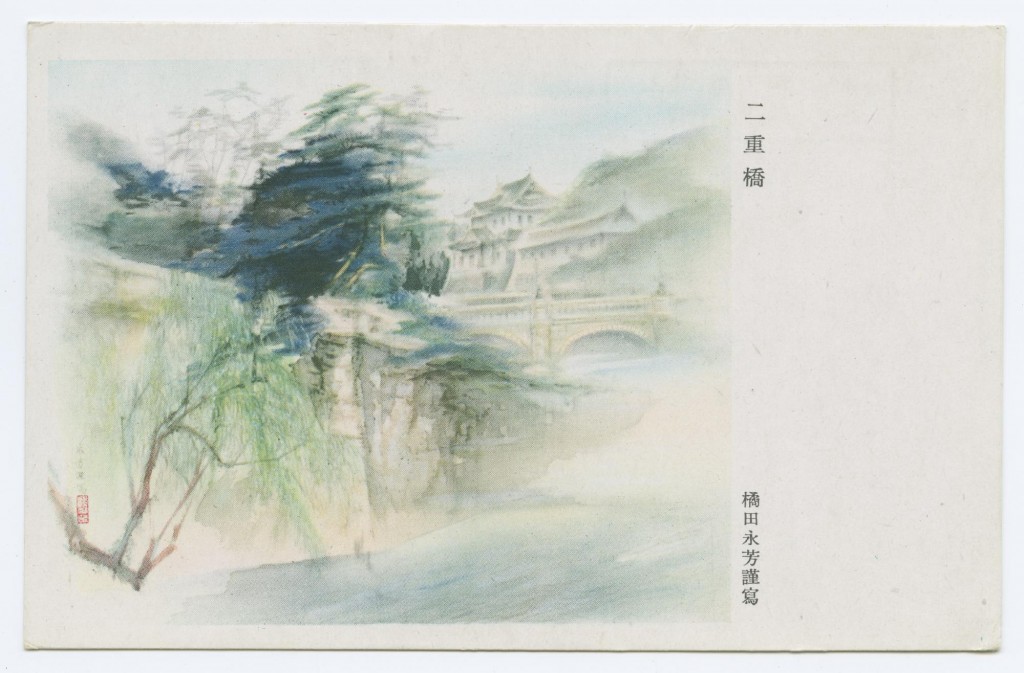

Despite the paucity of wartime postcards directly portraying Hirohito, however, the “emperor-centric” view of wartime Japan finds some corroboration in the East Asia Image Collection. For as Earhart explains, other symbols for the imperial institution abounded in Japanese visual propaganda. He specifically mentions the example of the “Double Bridge leading to the palace” (p. 33), of which there are many versions in this digital repository. The one below was produced to “console and support” the troops.

[ip1093] Nijūbashi 二重橋 (Double Bridge)

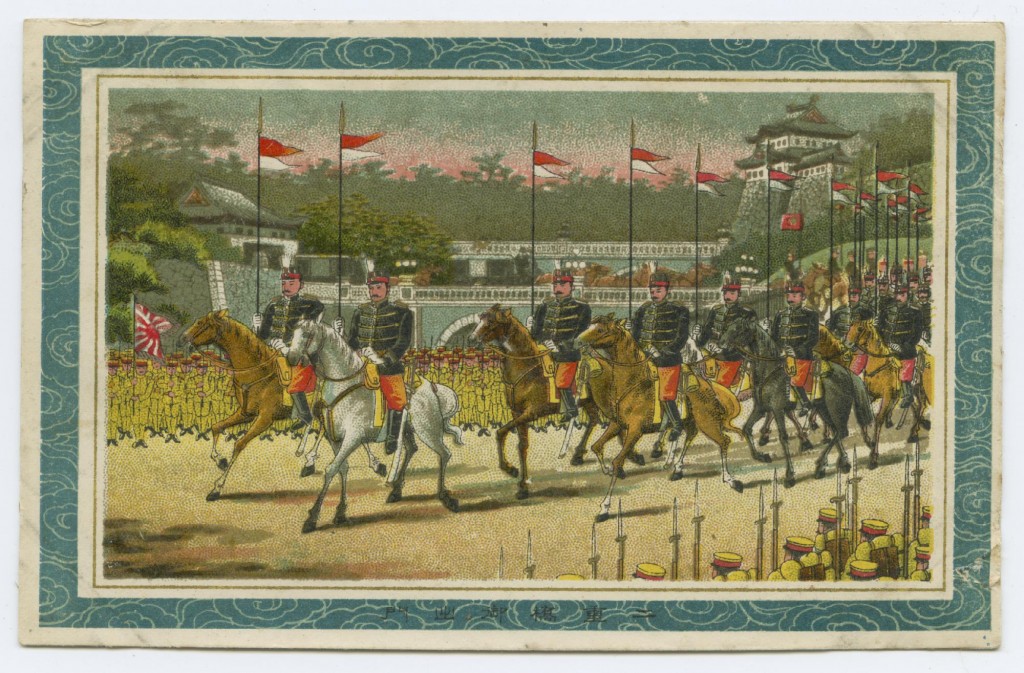

Printed on the reverse side of this Kitsuda Eihō (1902-1974) painting is a typical wartime postcard message: この絵葉書に慰問文をしたため皇軍将兵に送りませう。(“Let’s send words of support/consolation for our troops in the Imperial Army on this picture postcard”). Although this misty and impressionistic sketch may appear too abstract for a morale-building communique, contemporaries would have readily associated it with the emperor in his capacity as an overseer of military parades and deployments. The Taisho-era postcard below is one of many that illustrate the Double Bridge’s military connotations in Japanese iconography:

[ia0021] [Nijūbashi as Parade Ground for Troops]

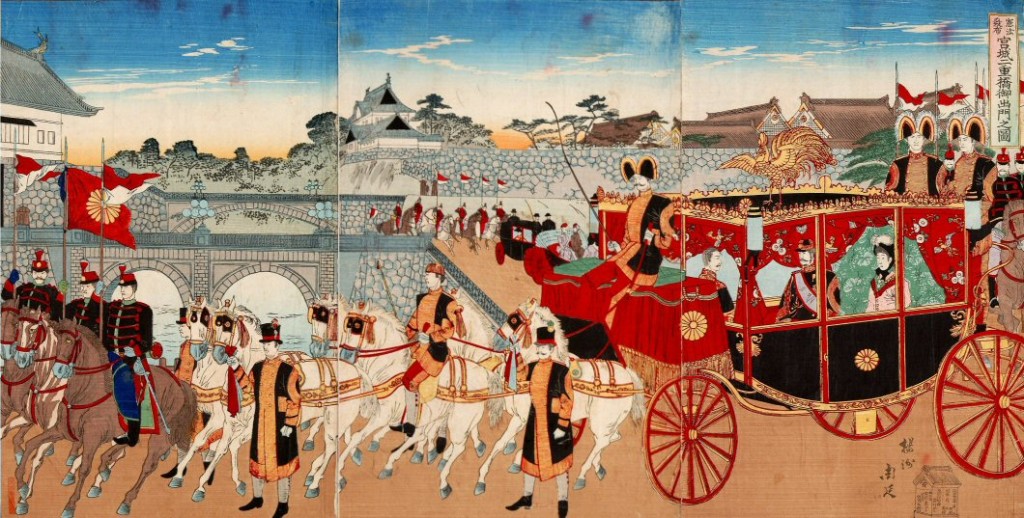

Several other cards from the prewar era similarly associate the Double Bridge with the imperial institution, either with troop reviews and parades, or as a stand-alone “famous site.” In his important study of the imperial institution as an element of nation-building in the Meiji period, T. Fujitani writes that military-victory celebrations included parades in front of Double Bridge as far back as 1894, in the opening phases of the Sino-Japanese War. The Meiji Emperor was a central figure at the imperial review of captured weapons and returned troops after the final battles of the Russo-Japanese War, as well. For this ceremony the emperor rode in an open carriage on a route that began with the Double Bridge, on April 26, 1906.[1]

Even preceding the picture postcard era, woodblock prints (錦絵) of the Double Bridge were popular. The print reproduced below was published as part of the celebration of the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution in 1889:

憲法発布宮城二重橋御出門之図 (Picture of the Constitution Promulgation at the Imperial Palace Double Bridge) 東京都立中央図書館特別文庫室

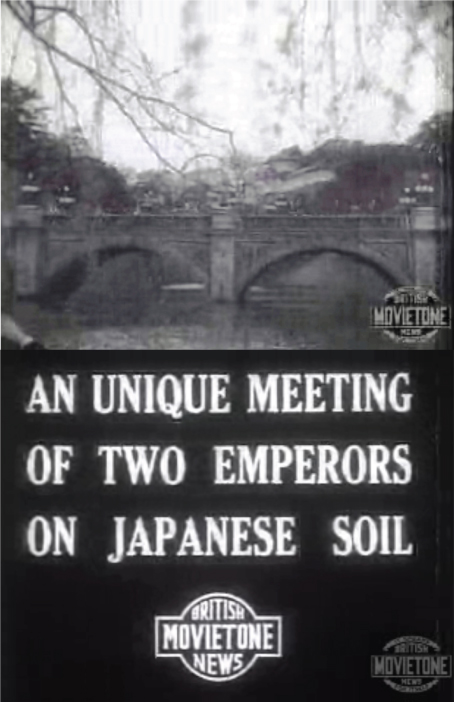

This British Movie Tone newsreel ends a short feature on Pu Yi’s 1935 visit to Tokyo with the famous scene of the double bridge with the Imperial Palace in the background:

Two Emperors Meet On Japanese Soil, British Movie Time Digital Archive Feb. 5th, 1935

After the Imperial Army’s defeat, American souvenir cards from the occupation era (1945-1952) continued to commemorate this erstwhile symbol of Imperial splendor and military might, as this hand-colored “Souvenir Card of Tokyo” illustrates:

[ac0041] Entrance to the Imperial Palace, Tokyo

To the present day, the Double Bridge has retained its luster: it is well maintained, photography-friendly, and at the center of the tourist route in Chiyoda-Ward, Tokyo:

(Lafayette College “INDS 130: Northeast Asia Interconnections” Summer 2013).

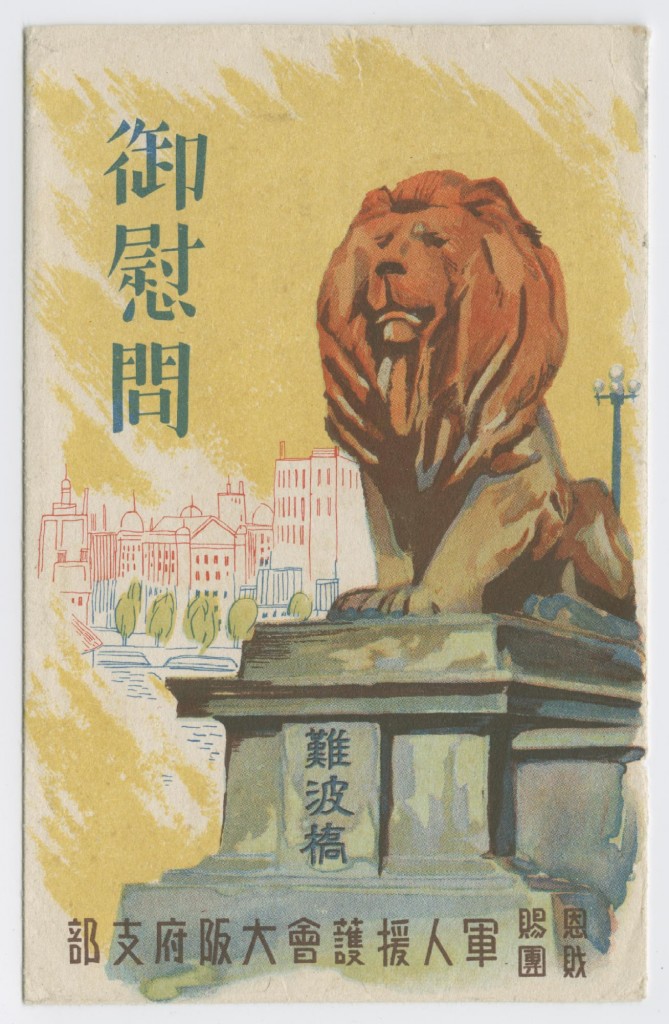

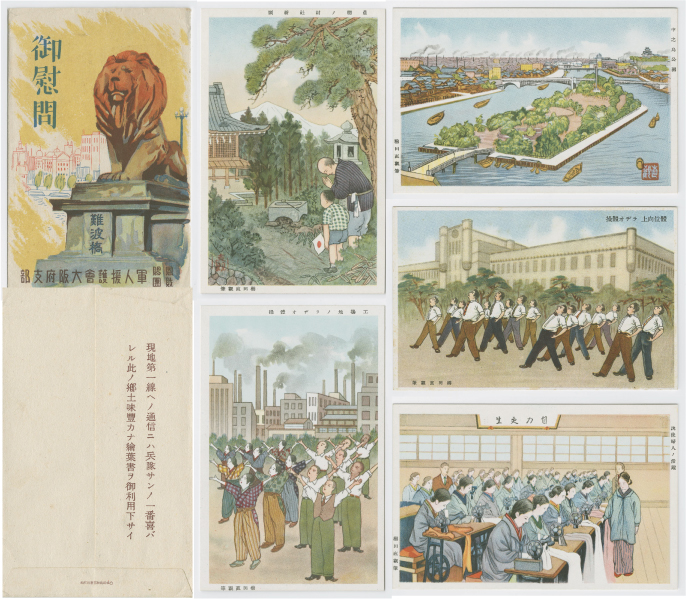

In sum, the Double Bridge was a symbol intimately connected to the imperial institution and the palace in Japanese mass media going back to the late nineteenth century, even before the era of picture postcards. As an element of wartime picture-postcard art, it lends some support to the emperor-centric view of the war. Nonetheless, wartime postcards in the East Asia Image Collection also reveal that other forms of loyalty and emotion were invoked to rouse the Japanese public to endure the war’s privations and cheer on the troops. Sticking to the theme of bridges, we turn our attention to an envelope cover for five “console/support the troops cards” (imon ehagaki 慰問絵葉書), produced by an Osaka-based organization known as the 軍人援護会大阪府支部 (Osaka branch of the Society for the Aid and Protection of Soldiers). The painting is of the “Naniwa Bridge” or “Lion Bridge” in Osaka:

[ip1317] [Console the Soldiers: Naniwa Bridge]

Here is a recent photograph of the same bridge:

Photo from “Osaka Info”

Like the “Double Bridge” in Tokyo, the Naniwa Bridge would have been a familiar site to recipients of postcards during the war years. However, instead of symbolizing the nation, the empire, or the imperial institution, Naniwa Bridge was utilized as a badge of civic pride in this set of “console the troop” postcards. Rather than preaching the gospel of emperor-reverence, these cards conjured memories of home. This intent is evident on the back of the envelope:

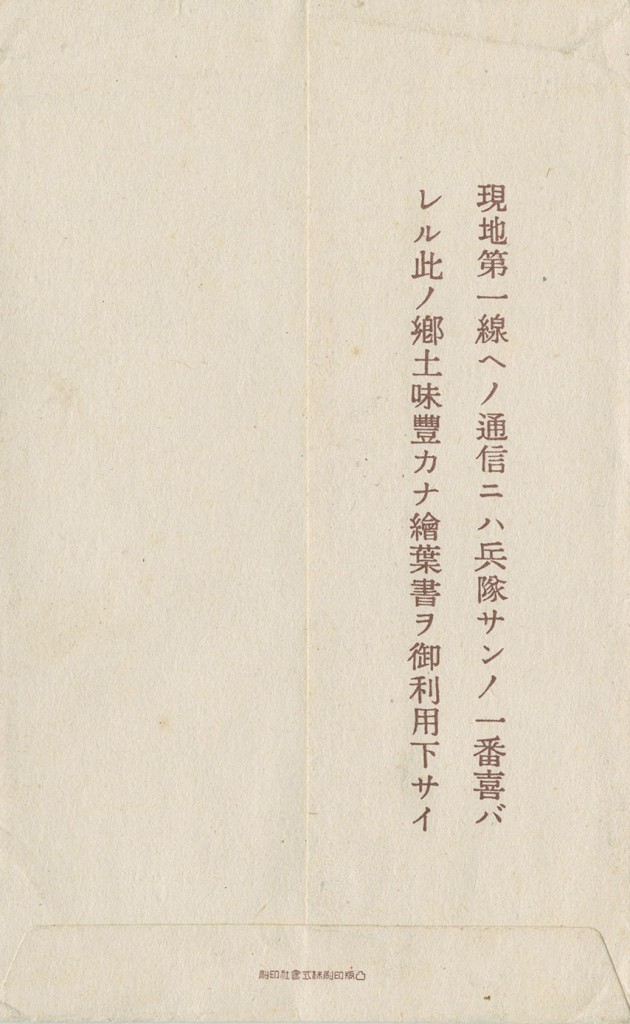

It reads: “In a letter to the front, to maximize the happiness of the troops, please use these picture postcards [which are] redolent with hometown/local flavor” (現地第一線ヘノ通信ニハ兵隊サンノ一番喜バレル此ノ郷土味豊カナ絵葉書ヲ御利用下サイ).

But what did “hometown/local flavor” (郷土味) mean in terms of wartime Japanese culture, ideology, and propaganda? What can an analysis of these ephemeral, yet very widely distributed, historical documents teach us about the culture of wartime Japan?

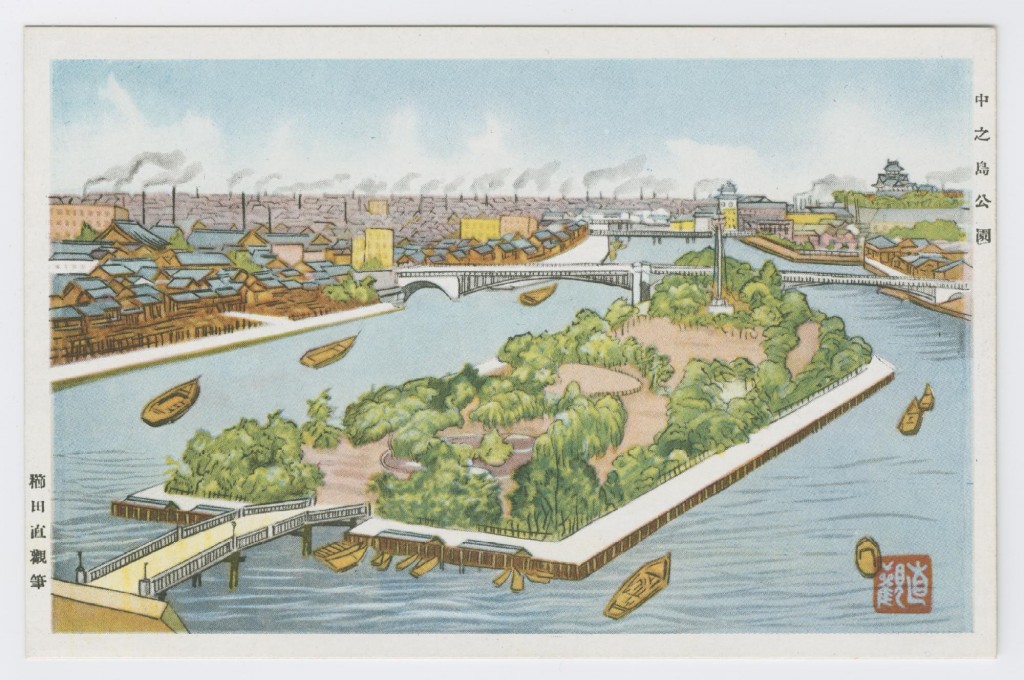

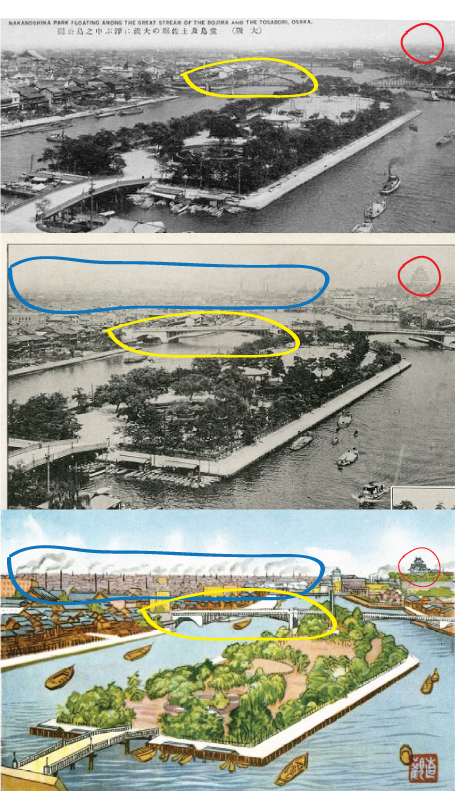

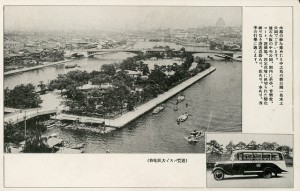

Besides the Naniwa Bridge, Nakanoshima Park, the Fourth Army Divisional Headquarters on the grounds of Osaka Castle, and scenes of a populace engaged in radio calisthenics, industrial labor, and shrine attendance represent “hometown/local flavor” in this set. All of these images were painted by 櫛田直観 (Kushida Naokan). Here is Kushida’s rendering of Nakanoshima Park:

[ip1319] [Nakanoshima Park]

The 1930s postcards below show that Kushida’s painting was of a “famous site” or 名所, a place easily recognizable and sought after by tourists. Postcards or photographs of “famous sites” validated the experience of “having been there”:

(from Kjeld Duits Collection online archive of postcards (#70116-0007)

(大阪百科ニューズ [Osaka-pedia News)

A side-by-side comparison documents changes to Osaka’s built environment over the course of the picture-postcard era. This comparison also throws a few of Kushida’s editorial decisions into relief, indicating how he accented features of the urban landscape to create a particular version of Osaka’s “hometown/local flavor.”

The view presented here faces eastward (and slightly southward) from a vantage point in the area now known as the “Rose Garden” on Nakanoshima. The yellow highlighting indicates the Matsuyama-machi-suji 松山町筋 bridge. This bridge was apparently reconstructed in the prewar period. In the top photo, the Matsuyama-machi-suji bridge utilizes a steel through truss design, while the middle photo shows the same bridge rebuilt using an open spandrel steel deck arch for the main span. The red highlighting indicates the main tower of Osaka Castle, which was rebuilt in 1931. The castle is missing in the top photograph, suggesting that the middle image is the more recent photograph, and that by 1931 the Matsuyamamachi-suji bridge had been reconstructed.

Kushida’s painting captures the built environment that is portrayed in the post-1931 photograph (the middle image), but necessarily abstracts the welter of detail to make some key points, ostensibly related to “hometown/local flavor.” While factories, chimneys, and smoke are visible in both photographic postcards, in Kushida’s rendering, the darkened smokestacks of Osaka stand out in clear contrast to the lightened rooftops, as the blue highlighting indicates. Industrial exhaust is prominent in other postcards in this set, as we shall see. In the context of wartime Japan, I read this valorization of billowing smoke as a confident symbol of Osaka’s continuous war production. At the same time, the highlighting of Osaka Castle adds to the “hometown/local flavor” of the scene.

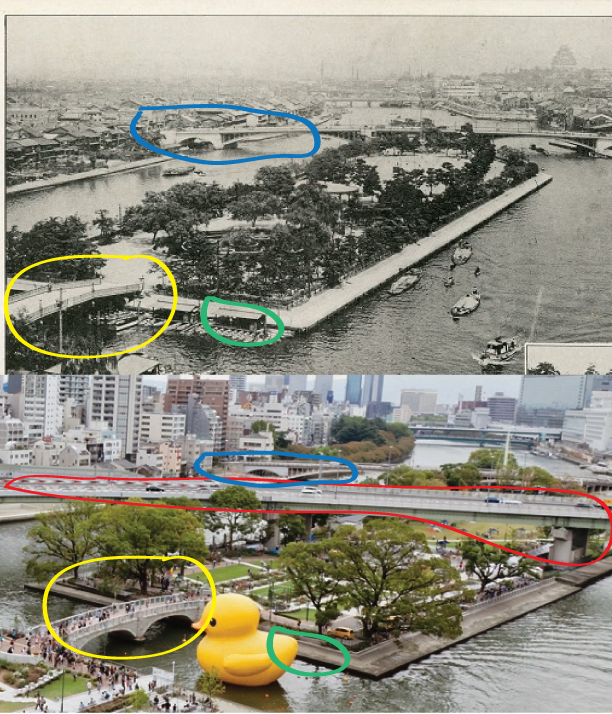

The contemporary photograph below shows how this vista has continued to change since 1945, probably as a result of the wartime bombing, but also due to postwar urban development:

(from Keihan L Magazine)

A before-and-after comparison:

The most obvious change since war’s end is the construction of the Hanshin Expressway Loop Line bridge 阪神高速道路環状線 through the middle of the park (indicated in red highlighting). The dense area of high-rise construction in the left-hand background is also a postwar development. The bridge to the island park has been reconstructed as a double-arched bridge (see yellow highlights), while the canopies and boat docks evident before the war are now gone (see green highlights). The Matsuyamamachi-suji bridge appears to have survived intact (see blue highlighting).

The big yellow duckling is not a permanent feature of the park. It is the floating creation of Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman. But if the search for images of “中之島公園” on the internet is any indication, the duckling has become strongly associated with this “famous site.” It made its first public appearance at Nakanoshima in 2009, then went on a global tour, to return in 2013 for another Osaka festival. See the Japan Times, Oct. 10, 2013).

The next picture in this series presents a more recent arrival to Osaka’s pantheon of famous sites: the Headquarters of the Army Fourth Division, which was completed in 1931:

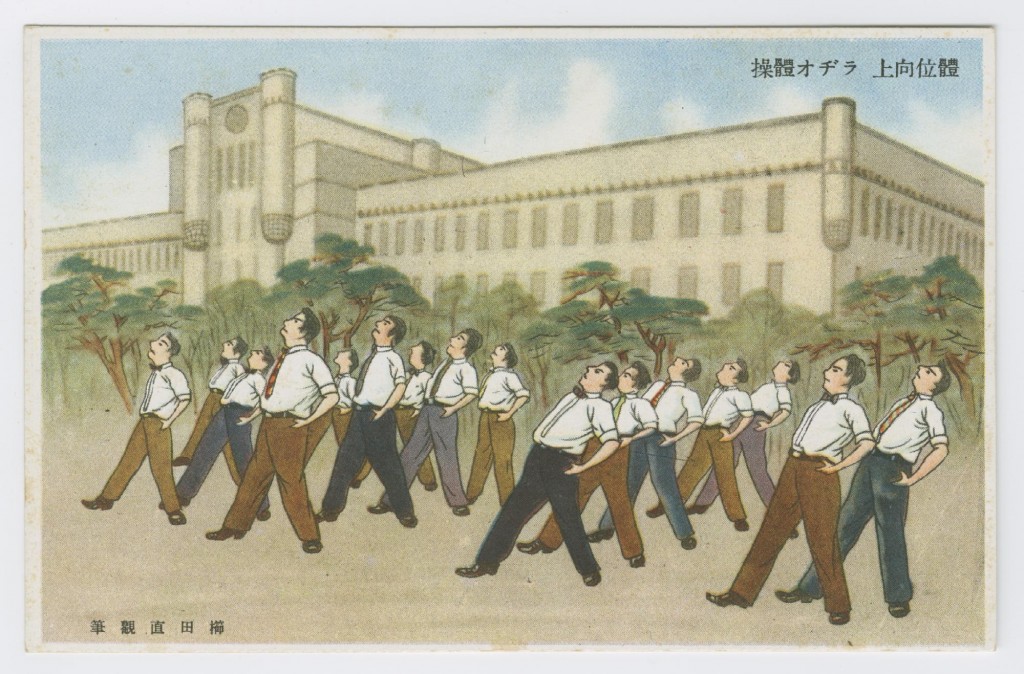

[ip1320] [Physique Improving Radio Calisthenics]

The caption on this picture postcard does not name the location, but emphasizes “radio calisthenics.” The facade of the building and the decorations on the corners indicate that this location is the parade ground in front of the Army Fourth Divisional Headquarters, which was completed with the restoration of Osaka Castle’s main tower in 1931.

Photograph by author (January 2012)

“Radio Calisthenics” themselves were launched in Japan in 1928, as a program to improve the health of the citizenry. They entered school life in the 1930s. On summer vacation, students were to attend the exercises and have their cards stamped to show to their teachers. But in 1938, the broadcasts were “incorporated into the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement.” According to Gregory Kasza, over 30,000 gatherings of these events “drew a total of 147 million people.”[2] David Earhart’s book has several photographs of these mass mobilization events from the war years (pp. 112-113). Earhart’s photographs feature bare-chested and militarily uniformed men exercising in unison. In Kushida’s painting, by contrast, we see a group of adult males wearing neckties. Presumably, these men are old enough for combat, but they are contributing to the war effort as production managers instead.

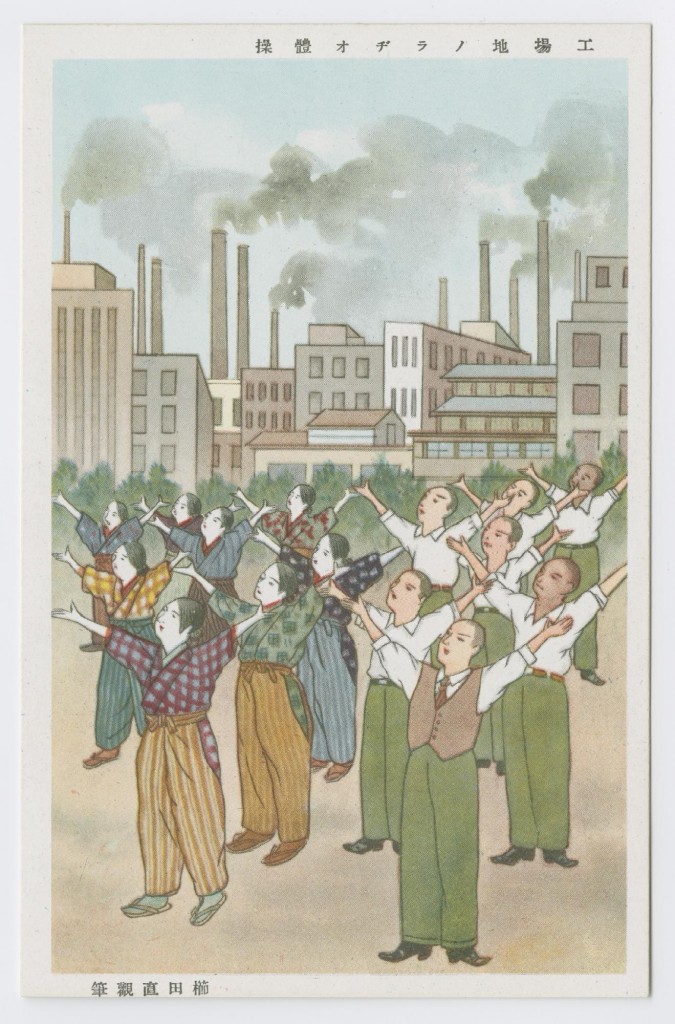

The second picture postcard of “Radio Calisthenics” more explicitly depicts wartime industry, and also presents men and women exercising together:

[ip1321] [Radio Calisthenics at the Factory]

As one would expect from a “National Spiritual Mobilization Movement” image, the women are wearing monpe pants and kimono-style upper garments. The men, however, retain their button-down vests and their white-collar shirts. This postcard suggests that the prohibitions on “non-Japanese” forms of adornment were more strictly applied to women than to men. As we saw in the Nakanoshima imagery, this postcard celebrates belching smokestacks as a badge of local pride. “Radio calisthenics” was a nation-wide practice, and was in part about synchronizing the nation’s citizens with an imperial beat drummed out in Tokyo. As Kenneth Ruoff notes in his study of nationalism and the 2600th anniversary of Jimmu’s birth, population-mobilizers planned many events in which subjects of the empire far and wide would synchronize their bodily movements in coordination with radio broadcasts.[3]

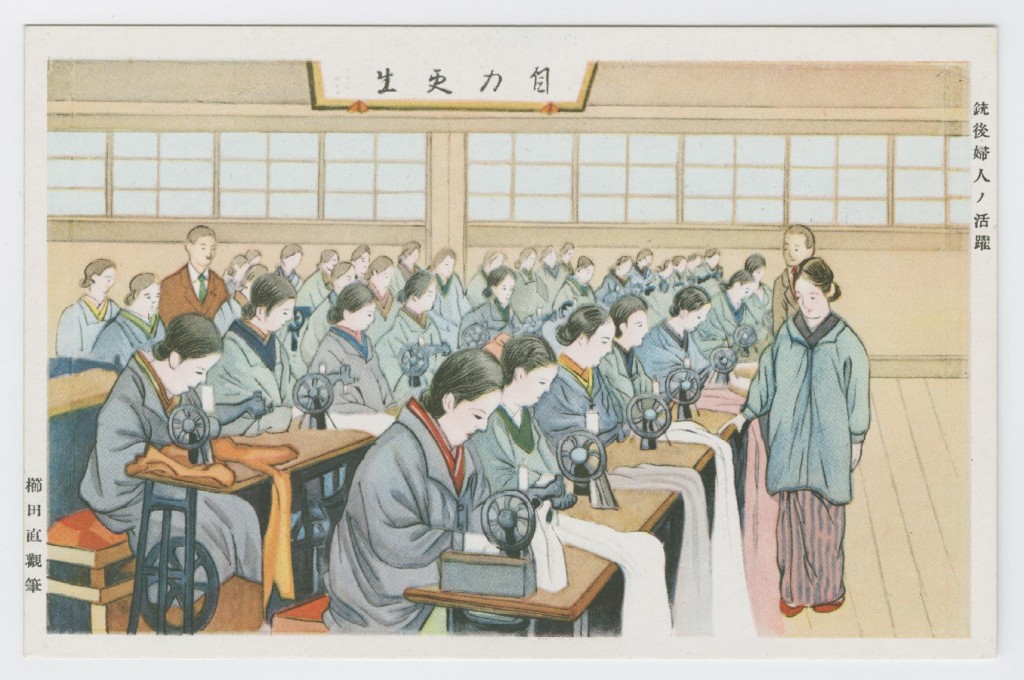

The next postcard in the series marks Osaka’s textile industry as a site of “hometown/local flavor.” Here, the white collared men pictured in the radio calisthenics postcards (shown above) appear to be supervising the kimono-clad women operatives:

[ip1318] Activities of Homefront Women

Posted on the sign above the operatives is the slogan “自力更生” which means “self-sufficiency,” or in this context, Japan’s perseverance in an expensive, prolonged war effort that was being waged in the face of sharply curtailed foreign trade.

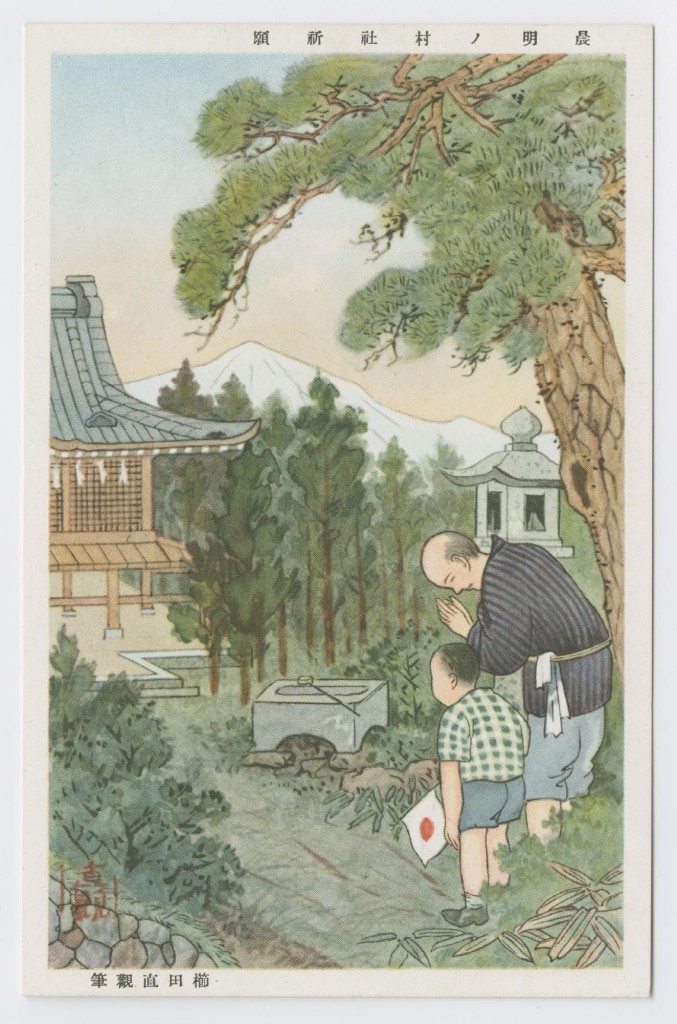

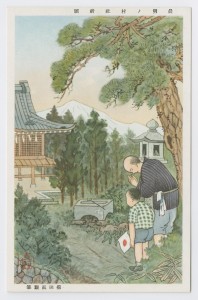

The last picture in the series highlights Shinto worship, and displays a Japanese hinomaru flag. In one sense, this iconography can be interpreted as a celebration of the emperor and nation, since Hirohito was Shinto’s high priest. Moreover, Shintoism, broadly conceived, underpinned the notion of Japan as a “land of the gods,” where the “gods” are Shinto deities.

[ip1322] [Dawn Prayers at the Village Shrine] 晨明ノ村社祈願

Nonetheless, “Shinto” is blanket term that subsumes many religious and political practices, institutions, and traditions. Turning Shinto into a national religion with a single figurehead (the emperor) and head priest was indeed a massive undertaking. James L. McLain has summarized this process in his textbook on modern Japanese history:

As part of its attempt to inculcate loyalty to the emperor and thus draw a mantle of legitimacy around itself, the new Meiji government embarked on a policy to place Shinto at the center of the nation’s religious life. Before 1868 Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples coexisted side by side, [and] most persons placed their faith in both kami and Buddhist divinities….

In 1868 there were approximately seventy-five thousand shrines in Japan, and the young Meiji leaders soon took the initial step toward creating so-called State Shinto when they arranged those centers of worship into a single national hierarchy….At the apex of the new pyramid sat Ise Shrine (伊勢の神宮), dedicated to Amaterasu, the progenitor deity of the imperial family and protective goddess of the entire nation. Next came … national shrines (官国幣社), and then [three] descending categories of civic shrines (諸社 or 民社). The imperial and national shrines received generous financial support from the central government, and their priests enjoyed the status of national civil servants, while prefectural and local governments supplied some funding to many lower-level civic shrines. [4]

[ia0017] [Ise Shrine, Showa Emperor and Empress]

The shrine in the Osaka “hometown/local flavor” postcard is a “sonsha” 村社, or “village shrine.” In the national Shinto hierarchy, the “village shrine” ranks the lowest of the three categories of “civil” shrines. (Below this level were the unregistered shrines that had no state affiliation, and thus stood outside of the rank system). These figures from the Japanese Wikipedia entry for “Shrine Hierarchy” (社格) position the “sonsha” in the pyramid of officially recognized shrines. The numbers in parentheses represent numbers of shrines:

Top Rank: Imperial Shrine (神宮): 1 (Ise Shrine).

Second Rank: National Shrines: (官国幣社): Grand (大) 68, Middle (中) 73, Small (小) 49, Special (別格) 44.

Third Rank: Civil Provincial Shrines (諸社の府社・県社): 1148

Fourth Rank: City/Town Shrines (諸社の郷): 3633

Fifth Rank: Village Shrines (諸社の村): 44,934

No rank: Unregistered Shrines (無格社): 59,997

According to a 1938 survey, about 60,000 (~50%) of Japanese shrines were unregistered. At the next level were the some 45,000 “village shrines,” like the one depicted in this picture postcard from Osaka. These shrines received property tax exemptions, but were not directly financed by the central government. One could translate this term, then, as “neighborhood shrine” and not be too far off.

The postcard itself draws the viewer’s attention to a stone cistern and dipper, where the elderly man and child purify their mouths and hands before paying ritual attention to the spirits. The mountain and a pine tree that dominate the image push the shrine structure to the corner. Only the small Japanese flag in the boy’s hand links this image to the larger national landscape.

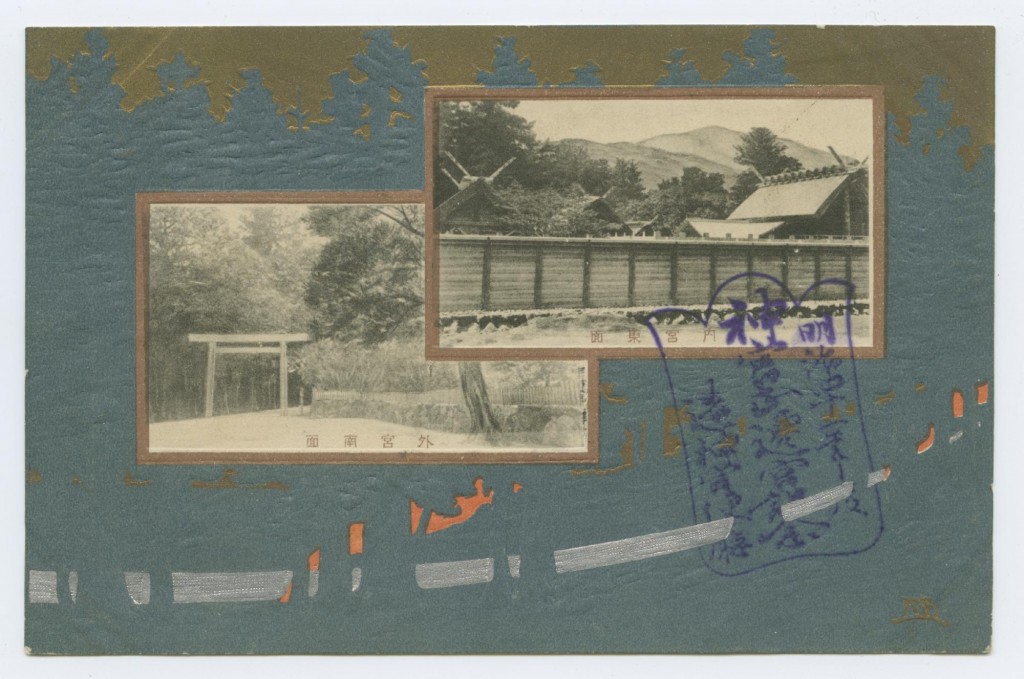

The “village shrine” stands in contrast to picture-postcard depictions of Japan’s major national shrines. Although statistics show that by the numbers, “village” and unregistered shrines were numerically preponderant, imperial and national state shrines were the ones usually represented in picture postcards. At the apex of the structure was the Ise Shrine:

[ia0022] Ise Shrine

[ia0022] Ise Shrine

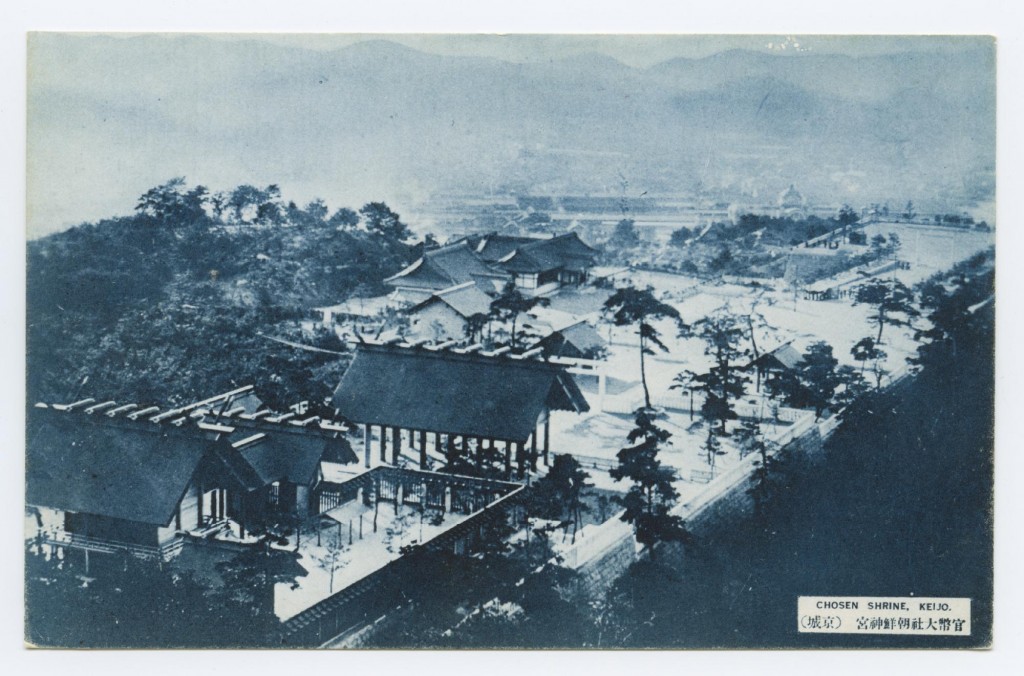

Unlike village shrines, high ranking shrines like Ise had extensive grounds, multiple buildings, and large Shrine Gates (torii) marking the entrances. National-level “grand shrines” were established in the capital cities of Japan’s colonies, in Korea, Taiwan, Karafuto (Sakhalin), the Kwantung Leased Territories, and the South Seas Islands (Nan’yo). The shrines in Seoul and Taipei were formidable, even forbidding, installations that had little in common with local places of worship like the one depicted in our series from Osaka:

[ip0497] Chosen Shrine, Keijo.

[ip0497] Chosen Shrine, Keijo.

[lw0209] THE TAIWAN SHRINE.

[lw0209] THE TAIWAN SHRINE.

Conclusions:

In this set of Osaka-themed postcards, we find an example of militaristic visual culture that was designed to appeal to a sense of “hometown” or “local” identity. While there is some overlap, this imagery seems distinct from the emperor-centric and nationally focused symbolism singled out by David C. Earhart as a hallmark of Japanese official war propaganda. These Osaka-produced postcards thus lend empirical support to alternative approaches to thinking about wartime Japan, to which we now turn.

For his contribution to the recent Stanford University Press anthology The Battle for China, historian Kawano Hitoshi interviewed over forty soldiers from the Japanese Army’s Thirty-Seventh Division to investigate sources of combat morale. These soldiers deployed to China in 1939 and engaged in battles across the continent, in Vietnam and in Thailand up until the end of the war. Kawano begins his essay by noting dominant views of Japanese motivation during the war:

Stereotypical portrayals of the Japanese soldiers emphasize ideological factors such as “fighting for the emperor,” “for the sake of the nation,” “the samurai spirit,” or “the Japanese spirit”… A puzzling view of the Japanese soldiers as superbly skilled and disciplined combat soldiers who were at the same time savage, brutal, and cold-blooded killers, like a “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” personality, dominates Western impression of the Japanese military.”… A more balanced view discounts the idealized image of the Japanese soldiers while recognizing self-preservation, comradely ties, social peer pressure, and family honor as equally important factors in motivating them to fight. [5]

Based on his close study of written Division histories, written testimony, and his interviews, Kawano offers an alternative view:

The individual Japanese soldier’s combat motivation was complex, multidimensional, and socially constructed. Contrary to the stereotypical image of the Japanese soldiers fighting for the emperor, most soldiers, in the Thirty-seventh Division fought for their families and local communities. Abstract notions of the country and the emperor … only constituted the background of their combat motivation. A pure form of nationalism, such as love of one’s hometown and the people around him,… was much more significant than the imperialist ideology in motivating soldiers to fight (pp. 352-353).

If Kawano is correct, then one might conclude that the five Osaka “console the soldiers” postcards discussed above found appreciative recipients on the front.

Barak Kushner also questions the emperor-centered approach to wartime Japan. In his The Thought War: Japanese Imperial Propaganda (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007), Kushner writes:

For a few–the staunch militarists and imperialists–the emperor may have remained the central icon behind mobilization for the war….For the vast majority, Japan’s war propaganda had stimulated feelings not about the emperor, but about Japan’s modernity….Wartime Japanese society envisioned the empire, with Japan at its pinnacle, as hygienic, progressive, scientific, the harbinger of civilization that Asia should strive to emulate…wartime propaganda often specifically depicted an advanced and modern Japan (pp. 10-11).

While Kawano interviewed veterans, Kushner investigated advertising, comedy routines, and especially studies of propaganda by civilian propagandists themselves, to draw his conclusions. The emphasis on factory production, supervised by modern men wearing double-breasted suits and neckties in the Osaka “console the troop” cards bears out Kushner’s contention. The appeal to local landmarks like Osaka castle, Nakanoshima Park, and neighborhood shrines also supports Kawano’s findings. Based on this admittedly fragmentary evidence, we conclude that these postcards open up possibilities for refining and augmenting our understanding of wartime Japanese visual culture, morale, and mobilization strategies.

Special thanks to Eric Luhrs for assistance in writing this post and to Professor D.C. Jackson for his guidance on bridge terminology.

back [1] T. Fujitani, Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 125-135.

back [2] Gregory James Kasza, The State and the Mass Media in Japan, 1918-1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 259.

back [3] Kenneth J. Ruoff, Imperial Japan at its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 57-59.

back [4] James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History (New York: W.W. Norton), University of Cornell Press, 2010), 267-68.

back [5] Kawano Hitoshi, “Japanese Combat Morale,” in The Battle of China: Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945, edited by Mark Peattie, Edward Drea and Hans Van de Ven (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 328-329.

Hi, i feel that i saw you visited my web site so i got here to go back the prefer?.I am attempting to to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its

ok to make use of some of your ideas!!

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Thanks, However I am having problems with your

RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I can’t join it. Is there anybody else getting

similar RSS issues? Anybody who knows the answer can you kindly respond?

Thanks!!

Adrese gelen istanbul Esenyurt hurdacı firması olarak hizmet veriyoruz.