Timothy Corrigan sums up Richard Dyer’s “Entertainment and Utopia” excellently in the quote:

Dyer’s essay, “Entertainment and Utopia,” originally published in Movie in 1977, spells out in clear terms with concrete examples that the Hollywood musical is less concerned with what utopia looks like (although certain movies attempt to depict ideal societies) than with what utopia feels like, and this is conveyed primarily through musical numbers that obey rules different from those of ordinary life. (466)

This plays on the absurdity of the musical. I don’t know about the rest of you, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen someone break out into a song about doing dishes or starting homework. Similarly, I’ve never seen someone unscriptedly sing about love or ephemerality. It’s just not natural. And that’s exactly it: utopia, in both the political and artistic sense, is not natural. It usually feels good, but it almost never looks “right”. Utopia is unnatural and absurd.

(Un)fortunately, Ghost Dog (Jarmusch, 1999) is not a musical. How do we relate it to the article? Well, for starters, it’s definitely absurd. The samurai overtones: absurd. The bumbling, child-like, idiotic gangsters (whom we have been conditioned to register as manly and intimidating): absurd. Urban isolationism: perhaps it’s not absurd to some people, but the fact that he can’t talk to his “best friend” is certainly absurd. In this way, Ghost Dog fits the bill of a utopian film; however, utopia is really a subjective term. Whose utopia is it? Not mine. Here’s why:

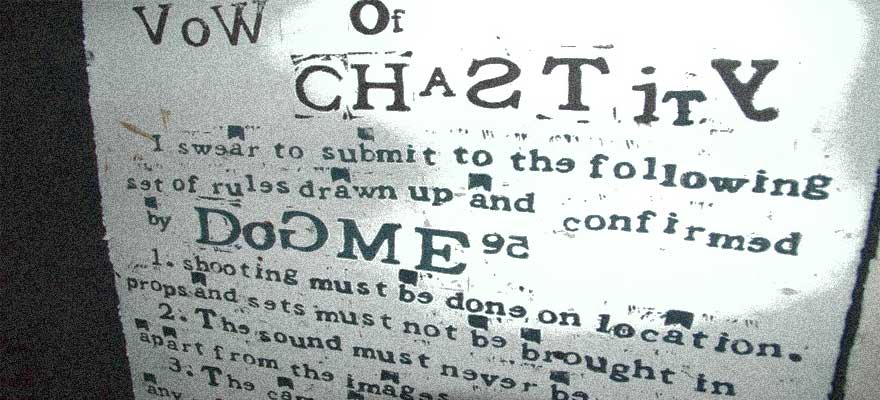

Like I said, it has samurai overtones. The “code” intertitles, the undying dedication to a master as a theme, and the holstering swishes all point to the samurai films of the past. These gestures are just as out of place as musical numbers are in musicals — the mob bosses even express this absurdity in their first round-table discussion. Yet, in my opinion, Jarmusch doesn’t go far enough in demonstrating his allusion to samurai film because the genre generally utilizes choreographed hand to hand combat and several wide angle and telephoto shots of nature and he does not do this in his film. Ghost Dog doesn’t look like a samurai film and therefore it doesn’t feel absurd like a samurai film should. It’s a boring hardwood film lacking the necessary veneer. As such, Ghost Dog doesn’t do it for me.

“But wait, I thought Dyer said it doesn’t matter what utopia looks like!” Dyer did say this, but I have to disagree with him almost entirely in this case. Jarmusch can tell his viewers a million times over that Ghost Dog is a samurai film — and believe me, he says it as many times as he can– but that doesn’t make it a samurai film. In the case of the samurai genre and many other genres, look and feel undeniably go hand in hand.