Category: Research Notes

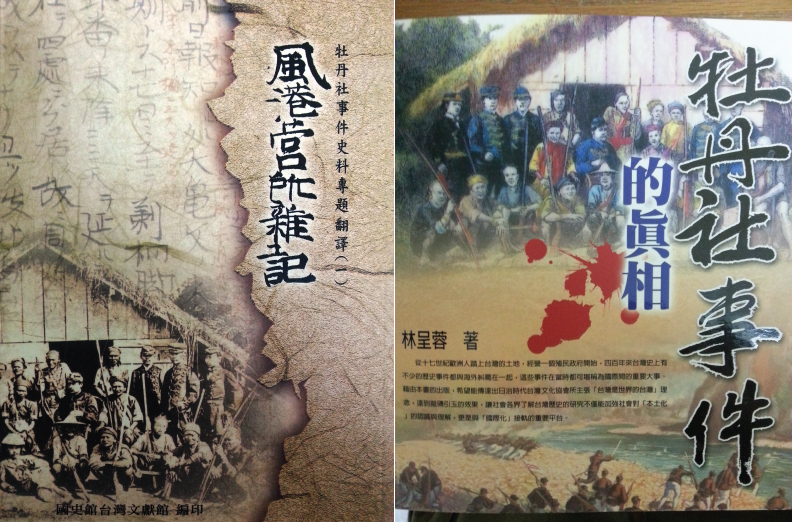

During the period of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan (1895-1945), thousands of photographs reached mass audiences via picture postcards. Seventy years later, many of these same images have enjoyed a revival, even though the empire has long since vanished. In this essay, I trace the history of one particular photograph: a group portrait of Saigo Judo (Tsugumichi), a handful of Japanese comrades, and his Paiwan allies in the Hengchun peninsula. This is one of the few surviving photographs of the Japanese military expedition to Taiwan in 1874. I begin with two fairly recent Taiwanese book covers that utilize an 1874 photograph that formed the basis for a widely disseminated 1908 postcard:

The title on the left, 風 港營所雜記: 牡丹社事件史料専頭翻譯 (Miscellany from Fenggang Camp: A Specialist Edition of Translated Historical Materials on the Mudan Incident) [1], is about as technical and narrowly targeted as a book can be. Except for the cover, there are no illustrations in this book, which was published by the Taiwan National Archives (Taiwan Historica) in 2003. To the right is a very different kind of publication: a colorful picture-packed general-audience book titled 牡丹社事件的真相 (The Truth about the Mudan Incident).[2]

The title on the left, 風 港營所雜記: 牡丹社事件史料専頭翻譯 (Miscellany from Fenggang Camp: A Specialist Edition of Translated Historical Materials on the Mudan Incident) [1], is about as technical and narrowly targeted as a book can be. Except for the cover, there are no illustrations in this book, which was published by the Taiwan National Archives (Taiwan Historica) in 2003. To the right is a very different kind of publication: a colorful picture-packed general-audience book titled 牡丹社事件的真相 (The Truth about the Mudan Incident).[2]

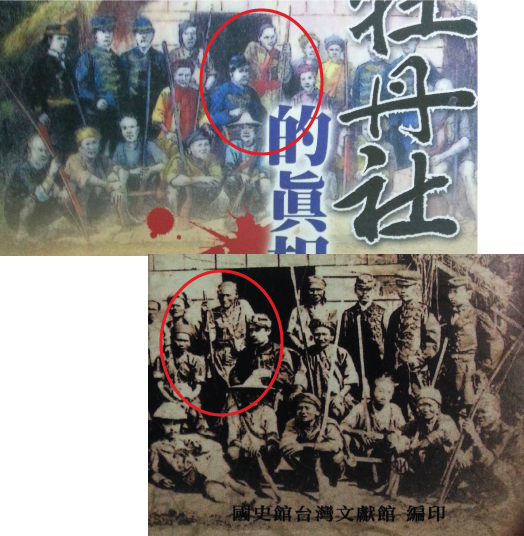

At first glance, it is easy to miss the resemblance between the two cover illustrations. One is a black-and-white photograph, and the other is a color drawing. Moreover, they are reverse images of each other. We can see from the cropped versions below, however, that the same scene is being quoted on both covers:

But which reproduction is “backwards”? Was Saigo Tsugumichi, the seated man in the center (circled in red) with the cap, looking to the right (from the cameraman’s perspective), or was he looking towards the left? I’m not sure. It seems that there are two lines of descent–from an 1874 photo and an 1875 etching–that have produced two separate genealogies of serial reproduction, both originating from a glass-plate negative that appears lost to the ravages of time.

But which reproduction is “backwards”? Was Saigo Tsugumichi, the seated man in the center (circled in red) with the cap, looking to the right (from the cameraman’s perspective), or was he looking towards the left? I’m not sure. It seems that there are two lines of descent–from an 1874 photo and an 1875 etching–that have produced two separate genealogies of serial reproduction, both originating from a glass-plate negative that appears lost to the ravages of time.

I. Introduction

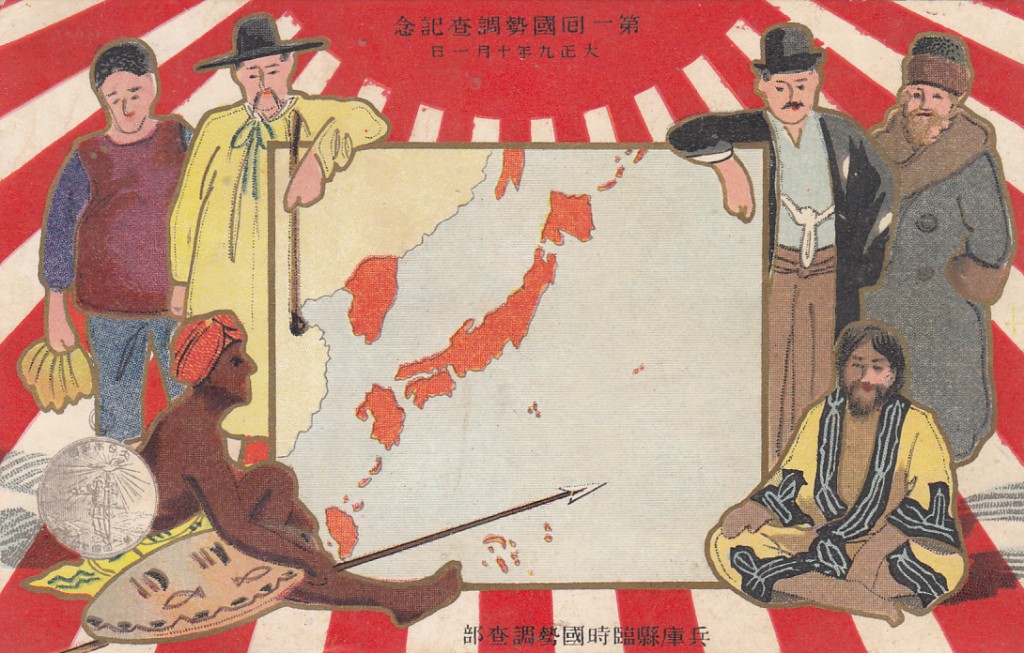

Japan’s East Asian empire is best known today for the military aggression and colonial policies that have caused so much diplomatic friction with China and Korea in the recent past. Less well remembered, especially outside of Japan, is a different image of the empire, of a vast collection of territories that was home to diverse peoples, climates, geographies, flora and fauna. The two postcards below–from 1920 and 1930–conjure a Japanese empire that stretched from subarctic Sakhalin to the tropical Micronesian islands.

A postcard from 1920 portraying the Japanese empire as a geographically far-flung, diverse assemblage of peoples and places. East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1567] [Commemorating the First National Census October 1, 1920]

The card above, from 1920, emphasizes the geographical reach and ethnic diversity of “Dai Nihon Teikoku” (Great Japanese Empire) by showing all areas under Japanese administration as “red” territories surrounded by peoples in a variety of folk costumes.

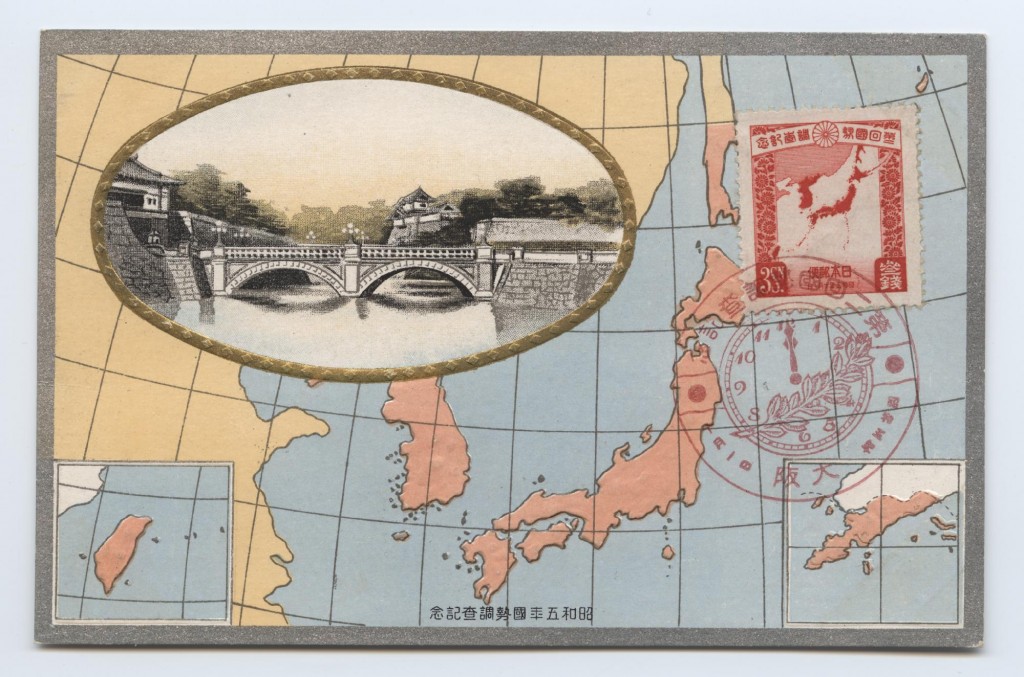

The card below emphasizes the centrality of the imperial throne and Tokyo to the empire, while clarifying its boundaries with solid colors on both the postcard itself and commemorative stamp that was issued along with it to celebrate the imperial census of 1930:

A 1930 Commemorative Postcard: Karafuto (southern Sakhalin), Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, Korea, Taiwan, the Kurile Islands and the Kwantung Leased Territory (southern Liaoning) with the Imperial residence (Tokyo) in the center. East Asia Image Collection, Michael Lewis Taiwan Postcard Collection, Lafayette College.

A 1930 Commemorative Postcard: Karafuto (southern Sakhalin), Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, Korea, Taiwan, the Kurile Islands and the Kwantung Leased Territory (southern Liaoning) with the Imperial residence (Tokyo) in the center. East Asia Image Collection, Michael Lewis Taiwan Postcard Collection, Lafayette College.

Such postcards promoted a popular geographic consciousness that imagined all of the territories colored red or pink as a single political unit. At the same time, other types of postcards highlighted the customs and environments of specific localities in the empire:

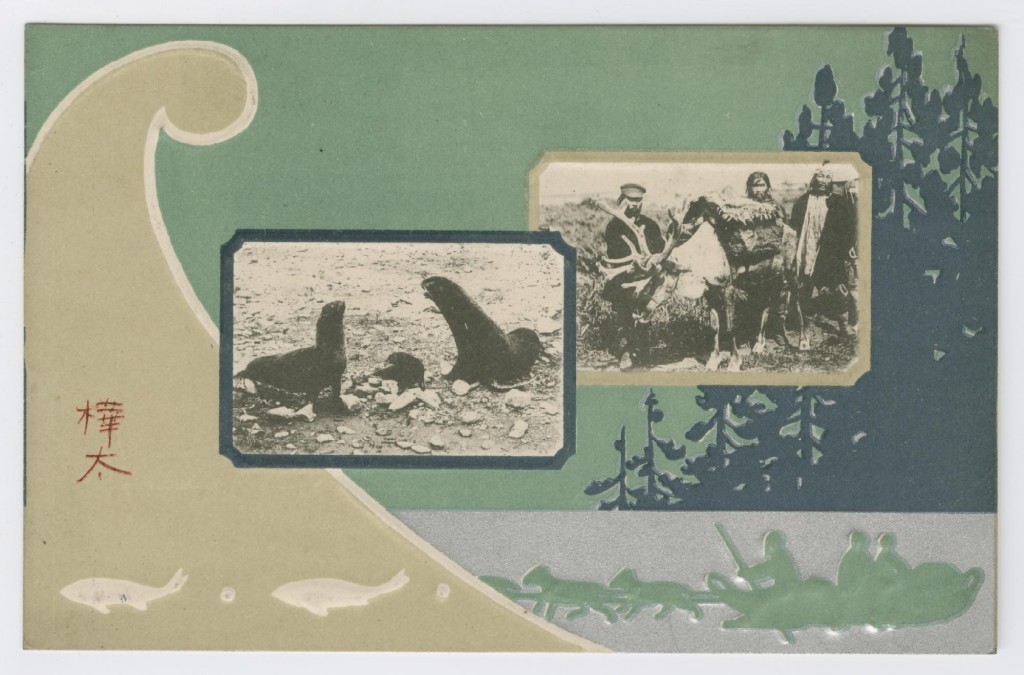

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1749] [Karafuto]

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1749] [Karafuto]

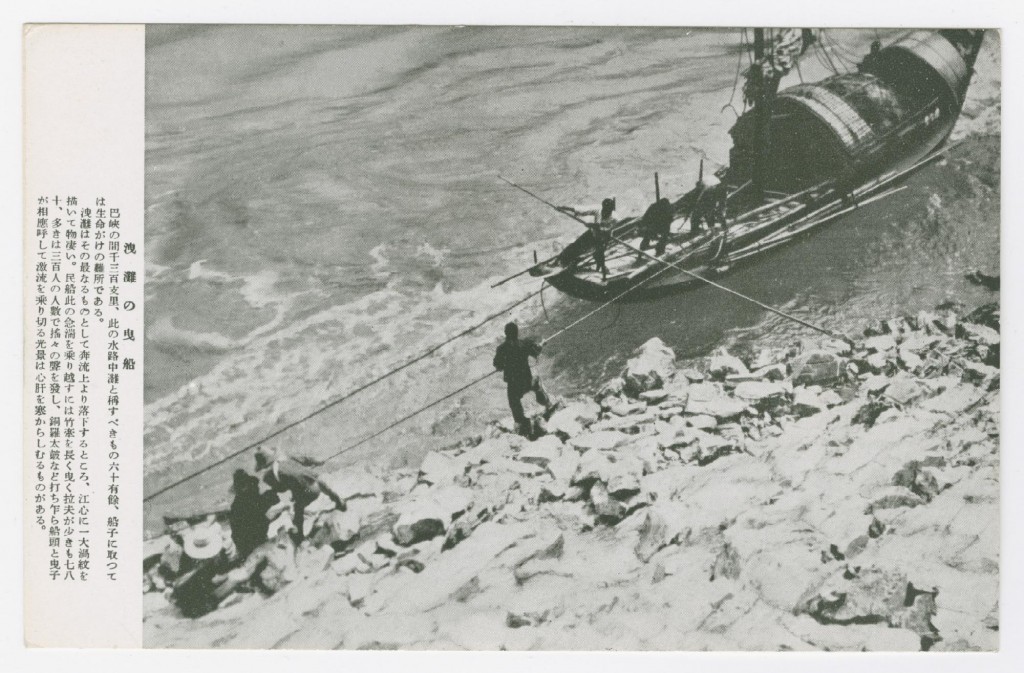

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1273] [Pulling Boats Upstream on Yangzi River]

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1273] [Pulling Boats Upstream on Yangzi River]

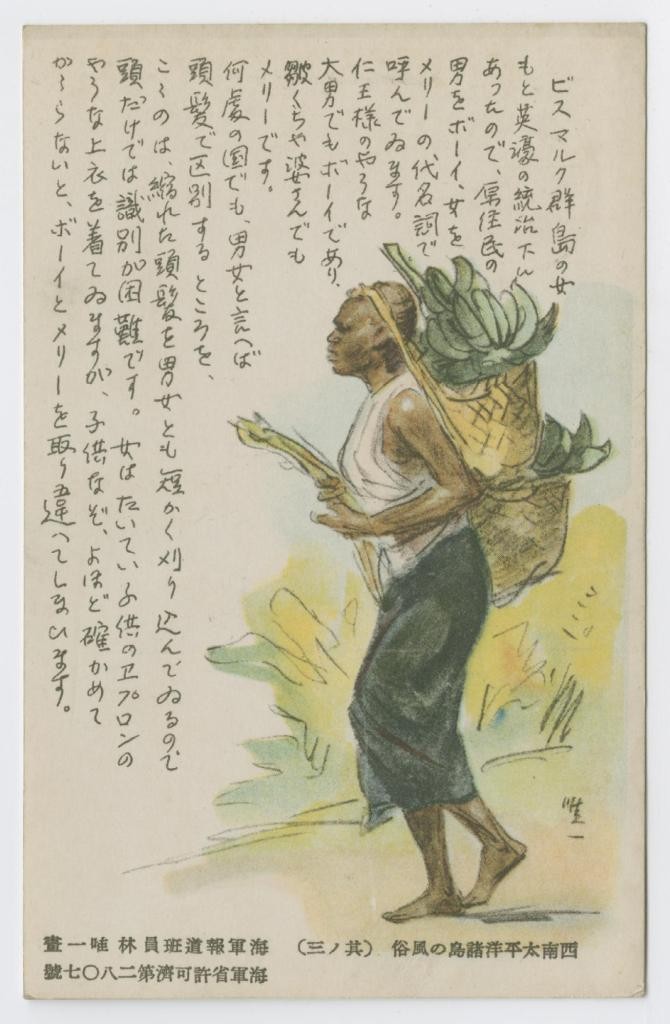

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1775] Bismarck Islands

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1775] Bismarck Islands

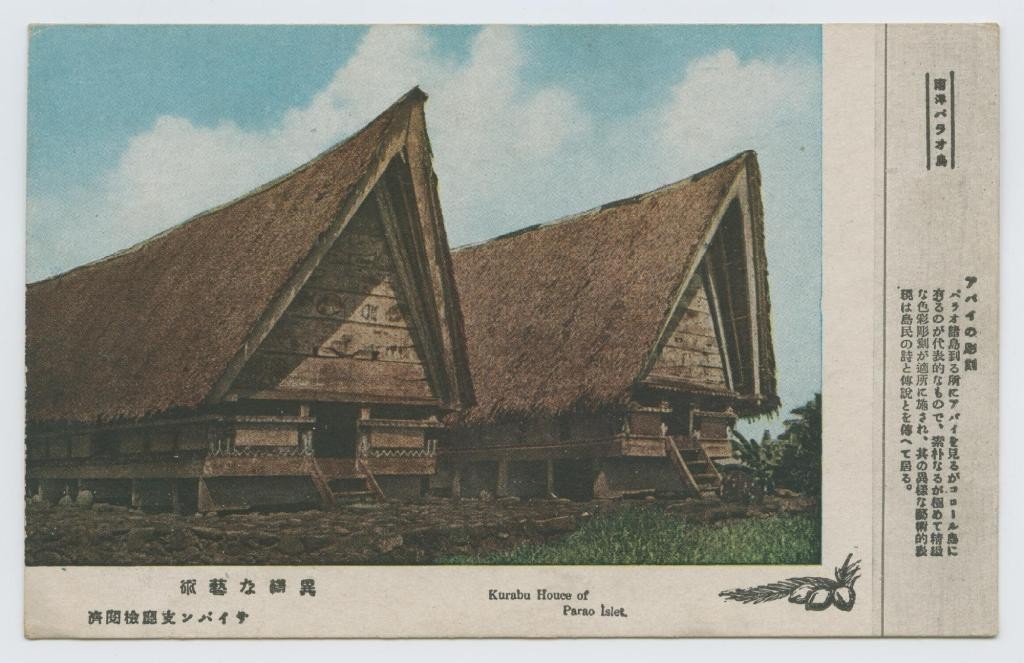

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1779] Club House in Palau

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1779] Club House in Palau

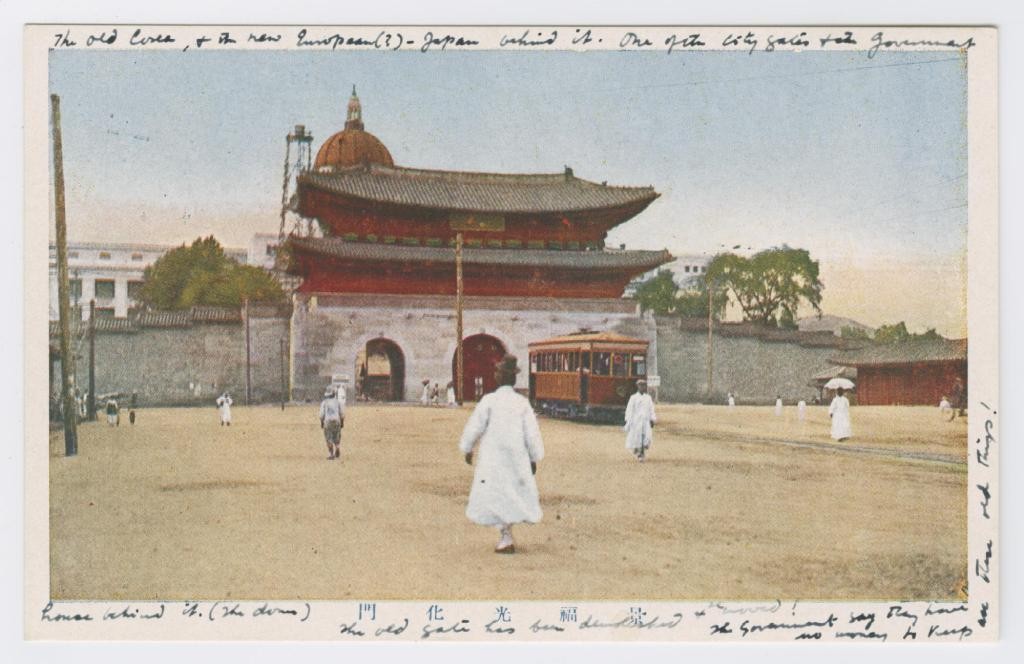

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1369] [Gyeongbok Gwanghwamun]

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip1369] [Gyeongbok Gwanghwamun]

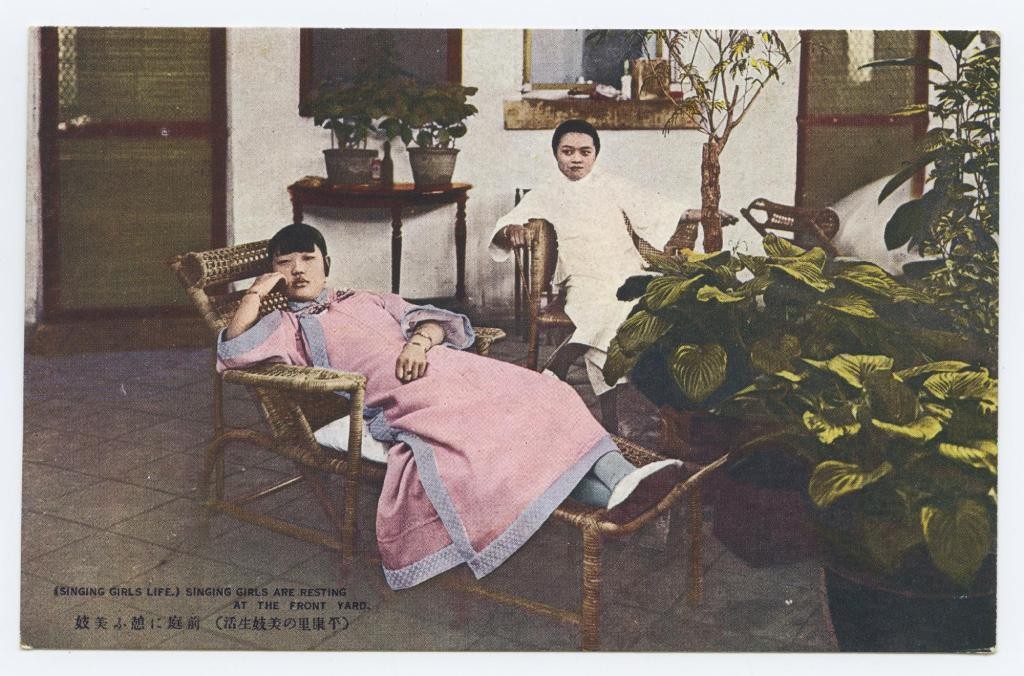

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip0634] (Singing Girls Life.) Singing Girls are Resting at the Front Yard.

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College [ip0634] (Singing Girls Life.) Singing Girls are Resting at the Front Yard.

The importance of these postcards for understanding how the empire was imagined, sustained, and inhabited has been generally overlooked by historians. As I hope to demonstrate is this series of posts, however, they are an important historical resource. For one, picture postcards propagated a complex and detailed (though highly selective) vision of empire-building and colonial rule to mass readerships in Japan for fifty years. Moreover, the motifs and themes institutionalized during colonial rule, as well as the photographs and postcards themselves, have continued to be reproduced in the post-colonial era. Importantly for historical research, picture postcards inspired, mimicked, distorted, amplified, and amended all other forms of Japanese print media, making them an ideal pivot for thinking about the visual culture, or visual economy, of Japan’s Asian empire, and modern imperial formations more generally speaking.

Picture postcards are resistant to systematic analysis because they are mostly scattered among private collectors. As ephemeral documents, they have generally eluded academic and state archiving procedures. Nonetheless, there are a growing number of institutional repositories that have made large collections available to researchers. Drawing upon these newly available resources, this series of posts will argue that a careful analysis of picture-postcard content, distribution, and commonalities and differences from other print media can provide new insights into the mechanisms and after effects of Japanese colonial rule in Asia in the early twentieth century.

II. Postcards and Other Forms of Mass Media

a) School Textbooks

To make the argument for the importance of postcard research for understanding Japanese imperialism, we begin with a discussion of how the picture-postcard medium contributed to the production of imperial space via the medium of public school textbooks. As Park Mijeong 朴美貞 has pointed out in a recent study, beyond their directly communicative function as captioned photographs, picture postcards served as source material for artists and authors who never actually visited Japan’s colonies. Among the media that drew upon postcard images were Ministry of Education textbooks [1]. Below, I will discuss a number of examples of this phenomenon, and demonstrate how textbook editors altered photographic evidence. In addition, I will show that in some cases, postcard publishers and textbook editors were drawing from the same pool of photographs, each one tailoring the imagery to different ends. The point of the exercise is to indicate how the study of the postcard medium can serve as a fulcrum into a fuller study of imperial photography, reprographic technology, and other meaning-making enterprises.

The four textbook images discussed below are taken from 1910 and 1919 Ministry of Education Primary School Geography textbooks. The first example, from Karafuto, not only reveals how a picture postcard prefigured a textbook illustration; it also shows how photographs were altered as they made the journey from negatives to etchings.

樺太 Karafuto

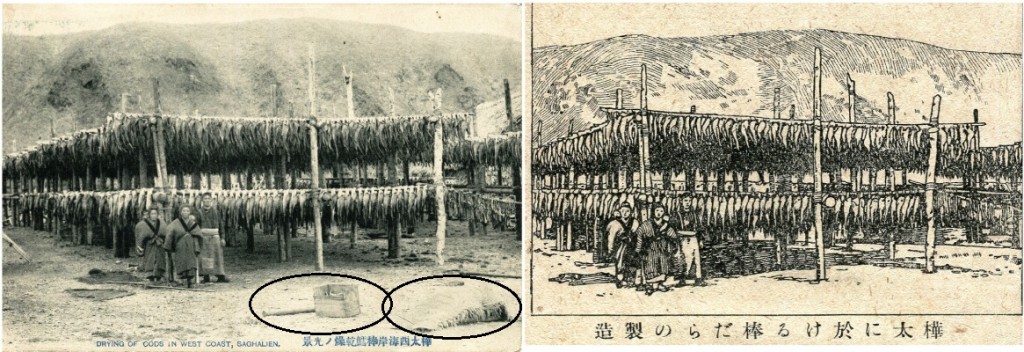

Left: 1907-1918 postcard from the East Asia Image Collection; Right: 1919 Ministry of Education Geography textbook illustration (文部省(編) 『尋常小学地理書巻二』 )

Left: 1907-1918 postcard from the East Asia Image Collection; Right: 1919 Ministry of Education Geography textbook illustration (文部省(編) 『尋常小学地理書巻二』 )

Note here that the “clutter” in the foreground of the photograph (circled), which appears to be boxes, poles, and woven mats, has been removed from the scene for the textbook etching. Since the postcard was produced before 1918, and the textbook was published in 1919, and the postcard contains more visual information than the etching, it is possible that the textbook editors simply adapted a commercially circulated postcard to illustrate Karafuto’s human and economic geography.

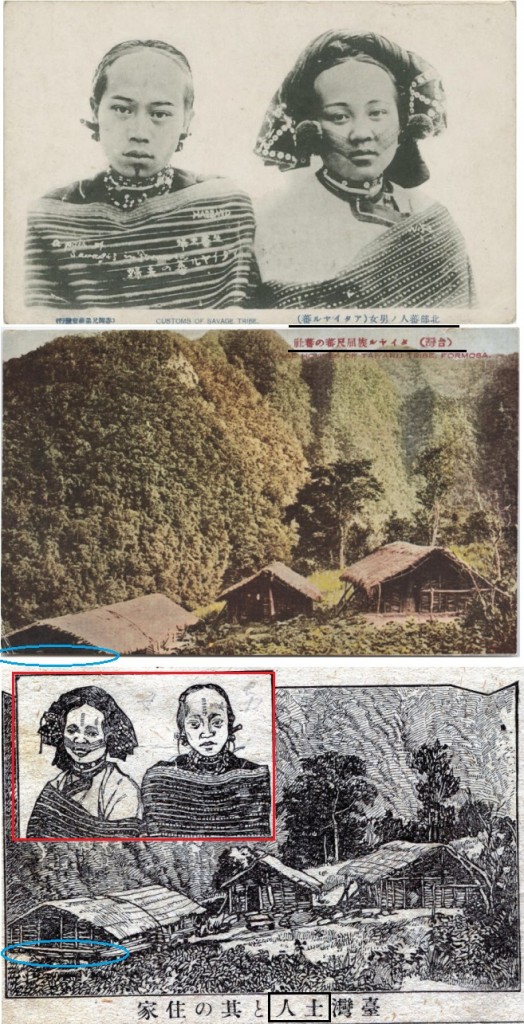

The next example is from the same 1919 textbook. Here the textbook designers have created a composite etching to illustrate “Taiwan Natives and their Housing” (台湾土人と其の住家) [see bottom image]:

台湾原住民 Indigenous Taiwan

Top image: 1907-1918 postcard of 1903 photograph (HUSBAND Wife A Pair of Savages in Formosa アタイヤル蕃の夫婦 East Asia Image Collection); Middle Image: 1907-1918 postcard of 1903 photograph “A Village of Kusshaku Atayal Aborigines” (「タイヤル族屈尺蕃の蕃社」 East Asia Image Collection); Bottom Image 1919 Ministry of Education Grade School Geography textbook illustration that combines the images from the top and middle postcards (文部省(編) 『尋常小学地理書巻二』 ).

Top image: 1907-1918 postcard of 1903 photograph (HUSBAND Wife A Pair of Savages in Formosa アタイヤル蕃の夫婦 East Asia Image Collection); Middle Image: 1907-1918 postcard of 1903 photograph “A Village of Kusshaku Atayal Aborigines” (「タイヤル族屈尺蕃の蕃社」 East Asia Image Collection); Bottom Image 1919 Ministry of Education Grade School Geography textbook illustration that combines the images from the top and middle postcards (文部省(編) 『尋常小学地理書巻二』 ).

In this instance, it is unlikely that the textbook illustrators used postcards as source material, though it is revealing to consider how their editorial preferences differed from postcard producers. For one, the portrait of the couple (enclosed in red) is reversed from the photographic print on the postcard. This is called “mirroring,” and it is a common occurrence in Japanese mass media of the early twentieth century. We also note that the foreground is cropped out of the postcard of “native architecture” (circled in blue), thus accentuating the vertical aspects of the scene.

Captioning, in a addition to image manipulation, allowed textbook editors to frame images to convey particular visions of imperial spaces and populations. Here, the textbook applies the word “dojin” 土人 (enclosed in black box) to the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples, which is an unusual usage. In the source photographs, the terms “Taiwan Banzoku” 台湾蕃族 or “Seiban” 生蕃 or “Banjin” 蕃人 are used without fail. The term “ban” 蕃 was the Japanese rendering of the Chinese word “fan” 番, which was applied to non-Chinese inhabitants of Taiwan in Qing-period documents. Japanese writers and editors continued this usage, but added the “grass radical” to the character. (In both of the postcards, which were produced in Taiwan, the term “ban” 蕃 is retained [underlined in black]). The textbook term “dojin” 土人 was regularly applied to Koreans, Chinese, Ainu peoples and the indigenous inhabitants of Karafuto in Japanese writing of the era. By substituting “dojin” for “banjin,” the textbook editors re-classified the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples as generic “natives” of the empire.

It is improbable that any Taiwan-based writer or editor, or Japanese person who had traveled to Taiwan, would lump Taiwan Indigenous Peoples (“banjin”) together with other peoples of the empire by referring to them as “dojin.” But from the viewpoint of Tokyo-based educators, perhaps such distinctions were unimportant, given the size and complexity of the empire by 1919. In the 1910 version of the same textbook, the Taiwan Indigenous People are indeed labeled as “banjin.” This loss of specificity with the passage of time and the expansion of the empire raises an important question: at what point does the cognitive effort to bureaucratize knowledge meet insurmountable challenges? In other words, does the granularity lost in the standardization of geographically varied terminology produce metropolitan conceptions of empire that obscure important distinctions among and within colonies, to the determinant of rulers and ruled?

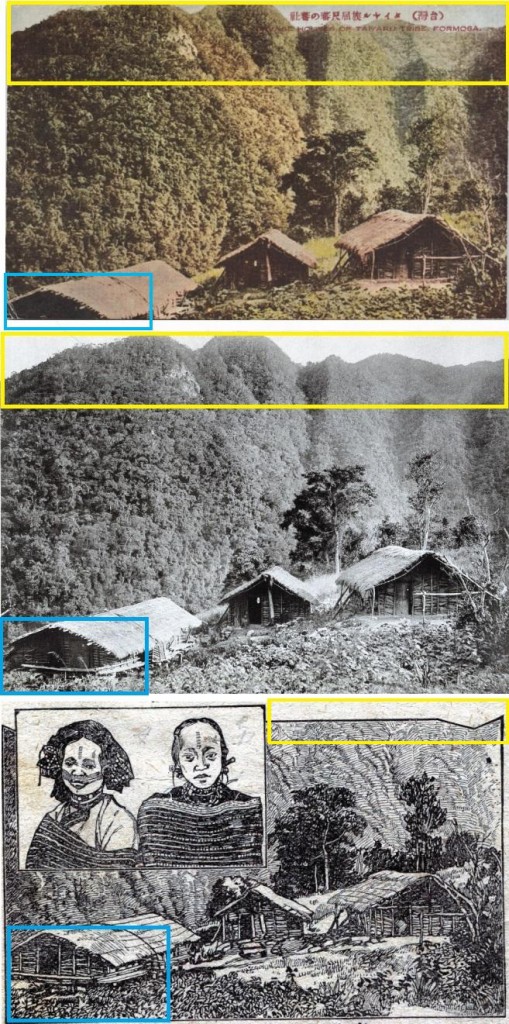

Moving from captioning choices to cropping strategies, we can see other editorial impulses on display in this image. In the next illustration, the original photograph is sandwiched between the picture postcard and textbook versions of the illustration. First, the textbook illustrator cropped out the mountain tops (see yellow enclosures), making it difficult to discern the steep terrain suggest by the photograph, and especially the postcard.

middle image from: 森丑之助 『台湾蕃族図譜第一巻』台北:臨時台湾休刊調査会 (plate 11)

middle image from: 森丑之助 『台湾蕃族図譜第一巻』台北:臨時台湾休刊調査会 (plate 11)

On the other hand, the postcard publisher cropped out the flat area in front of the structure in the foreground, obscuring architectural details and additional horizontal space. Thus, one could argue that one editor emphasized high altitude and isolation to connote an “Aborigine village” while the other tailored the setting to resemble a generic “native village,” commensurate with the captioning measures referred to above.

Given the high levels of primary-school attendance in Japan between 1910 and 1919, and the boom in postcard production that was coterminous, it is possible that these two mediums were the main conduits of visual information about the empire to Japanese citizens. Over the long course of imperial textbook production, pictures of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples eventually disappeared, though postcard production continued to flourish. The above example is provided to suggest a method for analyzing how a study of each medium can inform our understanding of the other, and why an analysis that excludes picture-postcards would be incomplete.

韓国・朝鮮 Korea

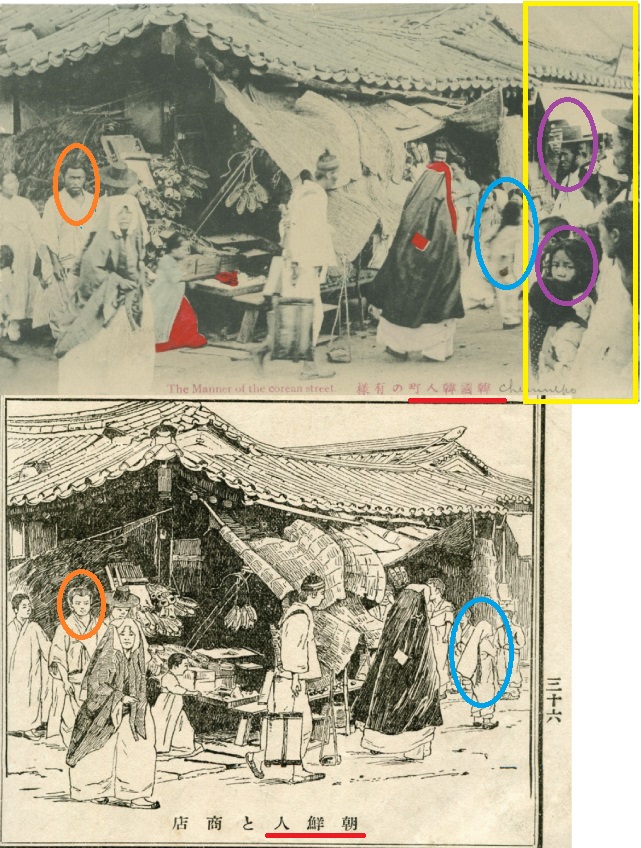

Moving on to Korea, which became a colony later than Taiwan, but soon eclipsed the island in terms of strategic, economic, and ideological importance, we also find interesting historical interplay between these two widely disseminated media. The postcard below was issued in 1907 or earlier, while the textbook image is from a 1910 textbook. If we juxtapose these images, we soon discover that there are a number of striking omissions and transformations in the textbook version (below).

Upper Image: 1900-1907 postcard, “[ip0981] The Manner of the corean street” East Asia Image Collection; Lower Image: 1910 Ministry of Education Textbook Illustration 『尋常小学地理書巻二』

Upper Image: 1900-1907 postcard, “[ip0981] The Manner of the corean street” East Asia Image Collection; Lower Image: 1910 Ministry of Education Textbook Illustration 『尋常小学地理書巻二』

First, the whole area enclosed by the yellow box has been cropped out. Here, a young female, an older man in a traditional Korean black hat (kat), and a man in a police cap (enclosed in purple) have been removed from the scene. Two of the highlighted figures in the photograph are looking at the camera, as is the bearded man highlighted with an orange circle. In the textbook version, the beard is gone, and the man staring into the camera has been replaced with a younger boy who is averting his gaze. The girl with a black pony-tail in the postcard had been given a head-scarf in the textbook illustration (blue circle). We may wonder if the intention of the editor was to create the sense of a slice of life taking place independent of the observer, because the base photograph reveals so much evidence that the cameraman was part of the scene, and was even perhaps unwelcome.

Has the bearded man been swapped out, while the police man and older Korean man were erased, to “tame” the scene by removing “rival” adult males? Lastly, the postcard uses the terminology “韓国韓人” (Koreans of the Korean Nation) while the textbook adopts “朝鮮人” (People of Chosen). It is perhaps no accident that the postcard was produced before Korea was officially put under Japanese colonial rule, while the textbook was issued after the “朝鮮総督府” (Chosen Government General) had been established.

As Korea eclipsed Taiwan in economic and geo-political importance, the space dedicated to Korean affairs in textbooks increased, as did the number of illustrations. There are many more examples of overlap and interplay between Korean postcards and Japanese textbooks to be explored.

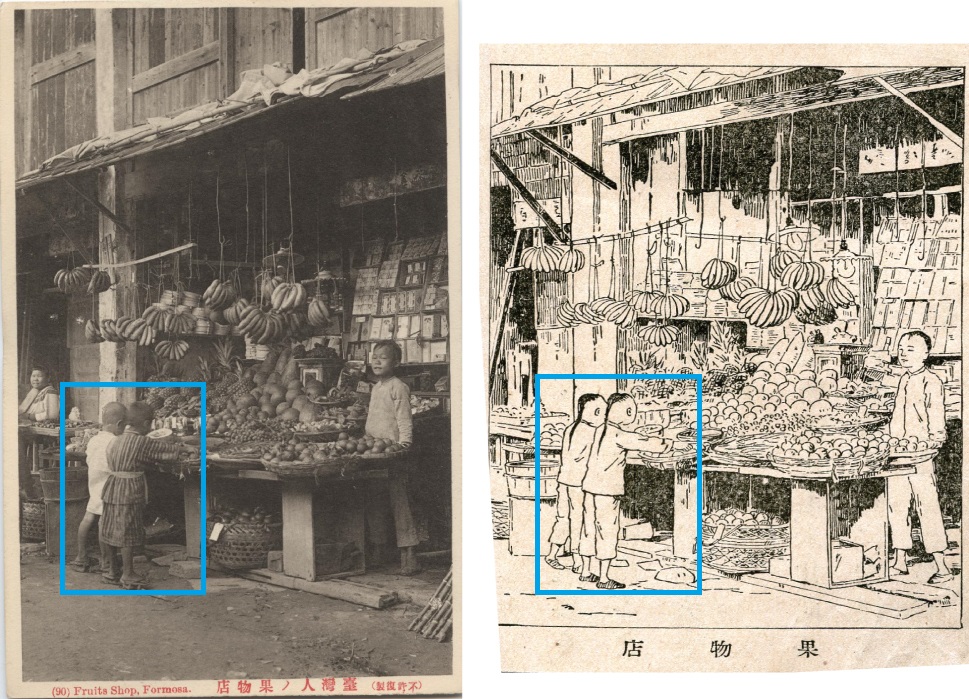

台湾 Chinese Taiwan

Left Image: 1907-1918 postcard “[lw0317] (90) Fruits Shop, Formosa” East Asia Image Collection.; Right Image: 1910 Ministry of Education Textbook Illustration 『尋常小学地理書巻二』

Left Image: 1907-1918 postcard “[lw0317] (90) Fruits Shop, Formosa” East Asia Image Collection.; Right Image: 1910 Ministry of Education Textbook Illustration 『尋常小学地理書巻二』

This last example is also drawn from a 1910 textbook. Here, the textbook radically alters the appearance of the two boys at a Taiwanese produce shop. In the postcard photograph, the boys enclosed in blue are wearing Japanese geta and one of the boys is wearing Japanese-style fabrics and a belt. In the textbook etching, the boys have been given regulation Qing “queues” or “pony-tails,” which in 1910 were the regulation hairstyles for all male Qing subjects. The etching also changes the clothing and the footwear of the boys to presumably accentuate their “Chinese-ness.”

In the foregoing, we have seen how postcards of Karafuto, Korea, and Taiwan propagated images that were found in Ministry of Education textbooks, while at the same time providing evidence that officially sanctioned imagery in the “geography” section of textbooks was significantly altered in the process of editing and publication. Considering that primary school attendance in Japan was nearly universal by 1910, and that postcards were being sent by the billions through Japanese mails annually during that period, we can assume that, if an image can found both media, like the ones above, that it was extremely well circulated, and worth analyzing in detail. In the next section of the post, I take up a broader category of publications: photograph collections either published or sanctioned by Japanese government organs. Here, we will see how commercial and official publishers were entangled in the production of imperial consciousness in early twentieth century Japan.

b. Expedition Photography and Picture Postcards

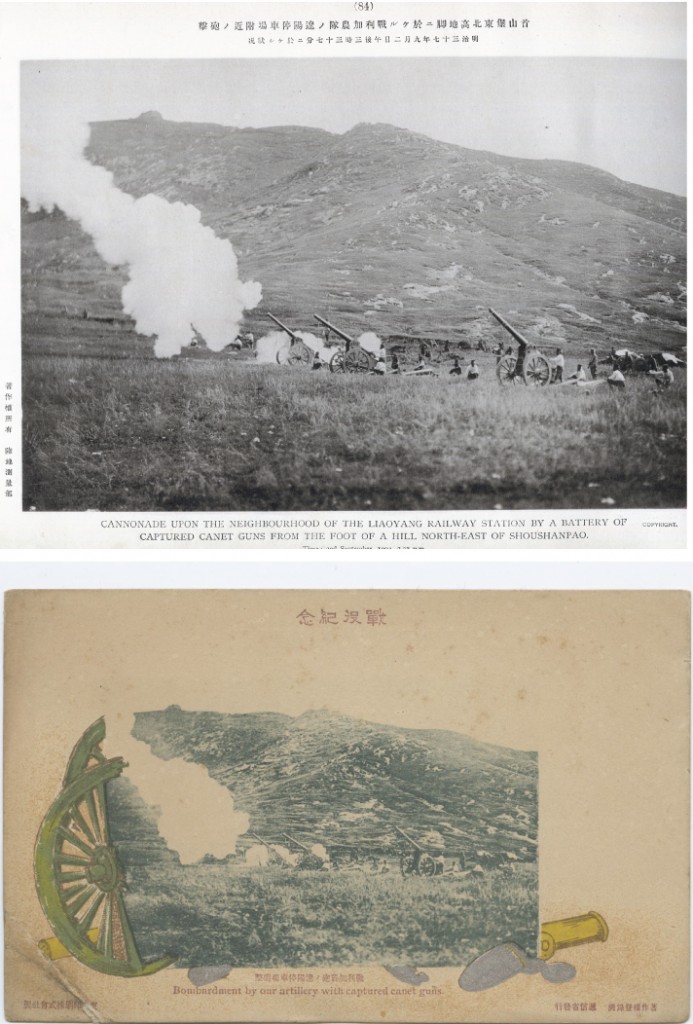

In addition to textbooks, picture postcards of Japan’s empire also reverberated with military photography and pictures generated during “punitive expeditions” in the colonies. The first large boom in Japanese postcard sales, in fact, was generated by government issued postcards based on war photography from the Russo-Japanese War. The postcard below is based on a photograph also published in an album set from the Photography Section of Imperial Headquarters. The photo was taken on September 2, 1904; the album was published December 10th, 1904, and the postcard was published on February 11, 1905:

大本営写真班 撮影、『日露戦役写真帖』 (The Russo-Japanese War, Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters). 東京:小川一真出版部; East Asia Image Collection

As Kogo Eriko has pointed out [2], publicizing Japan’s battlefield heroics and successes at home and abroad was a high priority of the government in 1904. Thus, Ministry of Communications officials appointed a crack staff of designers and printers to produce attractive, bilingual commemorative postcards that would capture popular and elite imaginations, as well as sell the war to foreigners. To enhance the rather stiff photography of the period, the above postcard is adorned with colored artillery wheels and a golden gun barrel or looking glass (I cannot tell). To make room for the embellishments, the photo is cropped and the caption shortened–information was sacrificed for beauty. We also note that over five months passed between the date of the photograph and the issue of the postcard set. Thus, unlike the mass-produced wood-block prints that celebrated the Sino-Japanese War for broad readerships a decade earlier, these official postcards cannot be considered as a type of news-disseminating media.

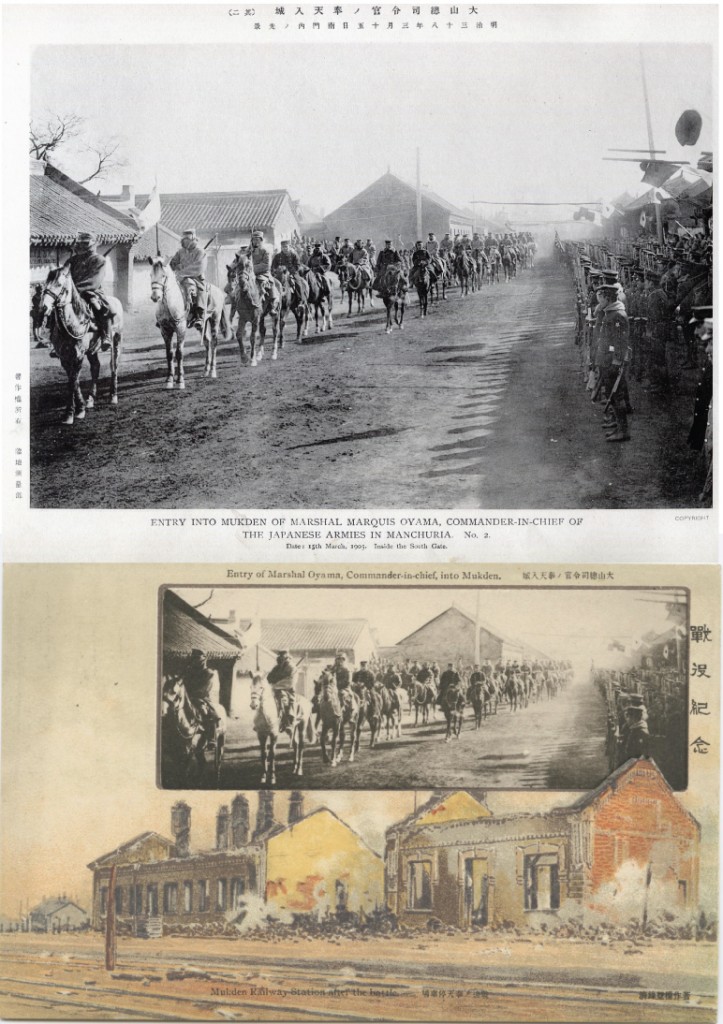

In the next postcard, the embellishments are even more pronounced, and actually compete with the (cropped) photograph for space on the card.

大本営写真班 撮影、『日露戦役写真帖』 (The Russo-Japanese War, Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters). 東京:小川一真出版部; East Asia Image Collection

This famous photo was shot on March 15th, 1905, after the capture and occupation of Mukden, and published as an element of this postcard six months later, on September 15, 1905. It was then published in the same official album series as the above photo on October 1, 1905. The photograph shows troops at attention, flags, and columns of horses in formation in a rather placid setting. The postcard, in contrast, envelopes the photograph in a painting of wreckage from a battle that preceded the stately procession in the photograph. This latter motif would re-surface in imagery of the destroyed Beidaying barracks in Mukden after the Japanese attack on September 18, 1931.

Picture Postcard ca. 1932 [ip0106] [Fengtian: Beidaying Garrison] East Asia Image Collection

Picture Postcard ca. 1932 [ip0106] [Fengtian: Beidaying Garrison] East Asia Image Collection

The extent to which the imagery made popular during the postcard boom of 1904-1906 prefigured imagery of Mukden/Fengtian in the 1930s is an avenue to be further explored in postcard research.

Since the government issued photo albums are all available online, as well as thousands of privately produced postcards, the commemorative postcard series can be measured against either the official photographic record or the commercially produced postcards to discern what type of message the Ministry of Communications was crafting with their wildly popular commemorative postcard series. I will be exploring these avenues in a coming post dedicated to this series of postcards.

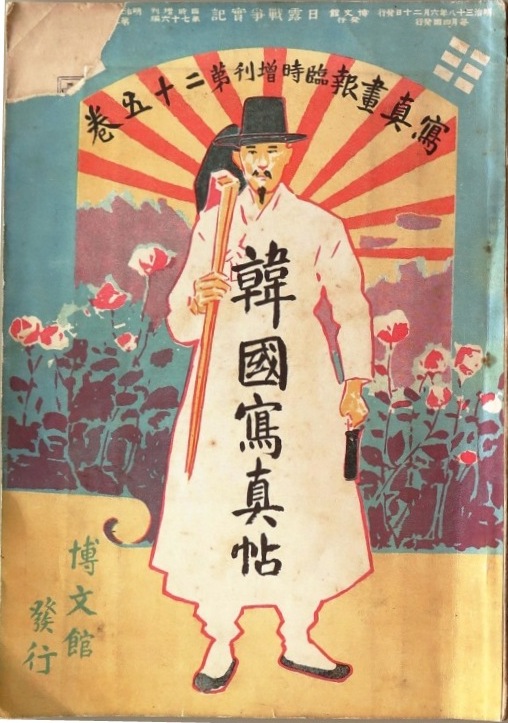

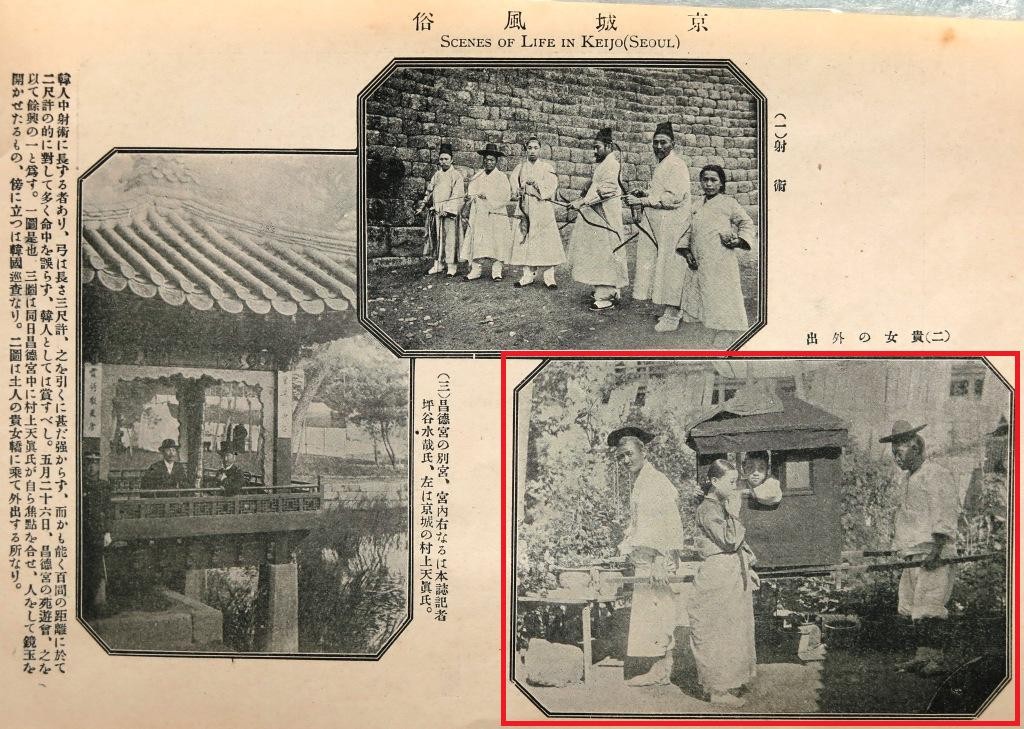

In addition to spurring the production of picture postcards of battle scenes, military heroes, artillery, and nurses, Russo-Japanese War photography also supplied the raw materials for “customs and manners” postcards of Korea. As Park Mijeoung has written, the “Korean Photograph Album” special issue of the popular Hakubunkan serial “Russo-Japanese War Journal,” published June 20, 1905, set the tone for popular Japanese images of Korean customs and national character. The cover of this issue has an easily recognizable Korean man with trademark black brimmed hat and white garments:

Korea Photo Album 『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905

Korea Photo Album 『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905

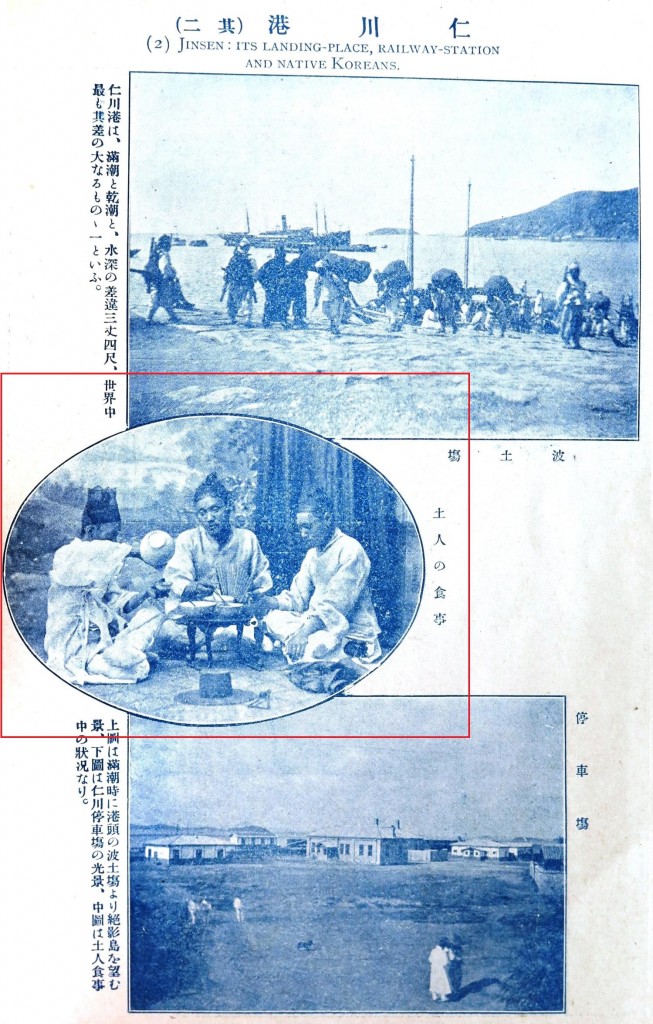

The photographic images printed in blue are from the 1905 Korea Photo Album. The half-tone prints used by these publishers are of lower quality than the collotype printing on the postcard prints (below) that circulated at roughly the same time [click here for guide to technical terms]. To make up for limitations imposed by technology and cost, magazine publishers used a variety of formatting devices like putting the image in new shapes, or tilting the image, or bordering it with a variety of designs, as we can see from all three pages reproduced below:

『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905 (Note the blue ink and use of an oval-shaped frame).

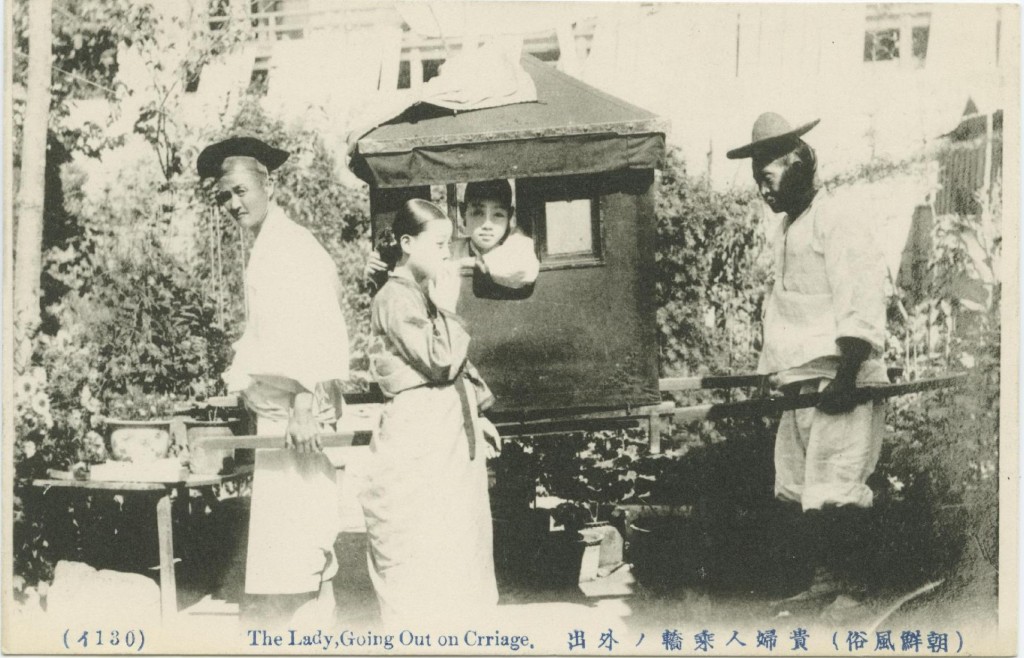

Picture Postcard from the East Asia Image Collection. Note the much higher resolution on the photographic print.

Picture Postcard from the East Asia Image Collection. Note the much higher resolution on the photographic print.

『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905. Again, the publisher has added interest to the half-tone prints by embellishing the illustrations with triple-lined borders and geometrically varied frames.

『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905. Again, the publisher has added interest to the half-tone prints by embellishing the illustrations with triple-lined borders and geometrically varied frames.

Picture Postcard from the East Asia Image Collection. Because postcards were often printed on sturdy cardstock, and used higher resolution printing processes, they sometimes contain the best surviving prints of certain photographs from the early 20th century.

Picture Postcard from the East Asia Image Collection. Because postcards were often printed on sturdy cardstock, and used higher resolution printing processes, they sometimes contain the best surviving prints of certain photographs from the early 20th century.

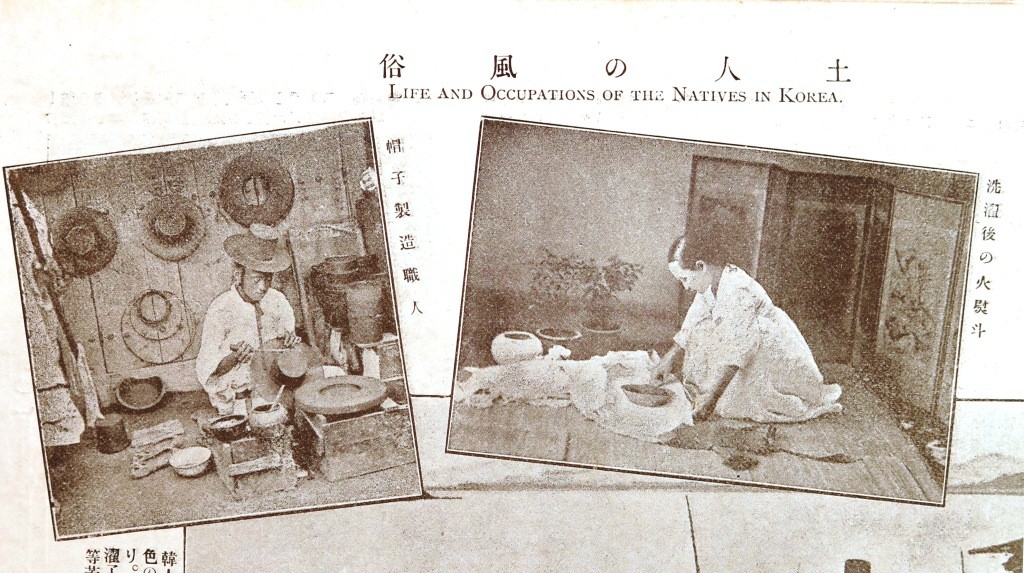

『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905. Half-tone prints.

『韓国写真帖』 東京:博文館 1905. Half-tone prints.

[ip0007] [Making Hats that all Married Men Must Wear] East Asia Image Collection. This postcard was based on the monochrome photograph used in the illustration above, but presents much more visual information, because it did not crop out the onlookers and bystanders in the hat-maker’s shop. It was produced in the late 1920s or early 1930s, when lithography was adopted to colorize photographs in the postcard industry.

[ip0007] [Making Hats that all Married Men Must Wear] East Asia Image Collection. This postcard was based on the monochrome photograph used in the illustration above, but presents much more visual information, because it did not crop out the onlookers and bystanders in the hat-maker’s shop. It was produced in the late 1920s or early 1930s, when lithography was adopted to colorize photographs in the postcard industry.

In the magazine photos, the first two pictures illustrate the customs of Incheon and Seoul respectively, while the third is intended to represent “Native Customs” in general (translated as Korean Life and Occupations in the magazine). In all of the postcards, the terms 朝鮮民衆風俗 or 朝鮮風俗 ([Popular] Customs of “Chosen/Korea”) are used instead, suggesting a uniformity of practices throughout the peninsula, and discontinuing the name “Kankoku” 韓国 in favor of “Chosen” 朝鮮.

A number of post-colonial theorists have suggested that the colony-wide dispersion of images, texts, and artifacts that promoted the idea of cultural unity within particular imperial administrative units contributed to a precious sense of nation, which was later revived and energized in the post-colonial period. If such is the case, Japanese postcards of Korea were a likely informed cultural nationalism on the peninsula in the early 20th century.

The persistence of some forms of imagery, such as the three images above (which were popular postcard motifs into the 1930s) and the disappearance of others (like portraits of the royal family) from 1905 to 1945 corroborates the view that colonial imagery was dynamic and suggests that longitudinal studies of postcard production can contribute to our understanding of the possible colonial-period antecedents of modern Korean nationalism, as well as shed light on the nature of colonizer perceptions of the empire and its inhabitants.

While the Russo-Japanese War ended for most Japanese in September of 1905, it continued for several years in Korea and Taiwan. In Korea, the instantiation of a protectorate after the war, the demobilization of the Korean Imperial Army, and generalized violence associated with building a supply corridor on the peninsula during the war, fomented large-scale armed resistance against the Japanese occupiers. Much of this armed conflict is today known as the suppression of the “Righteous Armies (義兵戦闘).” These battles raged well into 1909, with horrific losses on the Korean side.

Concurrently, imperial forces engaged thousands of Taiwanese combatants in the mountainous interior in the decade following the Russo-Japanese War, mostly in order to more efficiently tap the wealth of Taiwan’s camphor forests. These so-called “punitive expeditions” were commemorated with numerous official and commercial photo albums, which both retrofitted older postcards into the visual narratives of conquest, while also providing the raw material for new postcards.

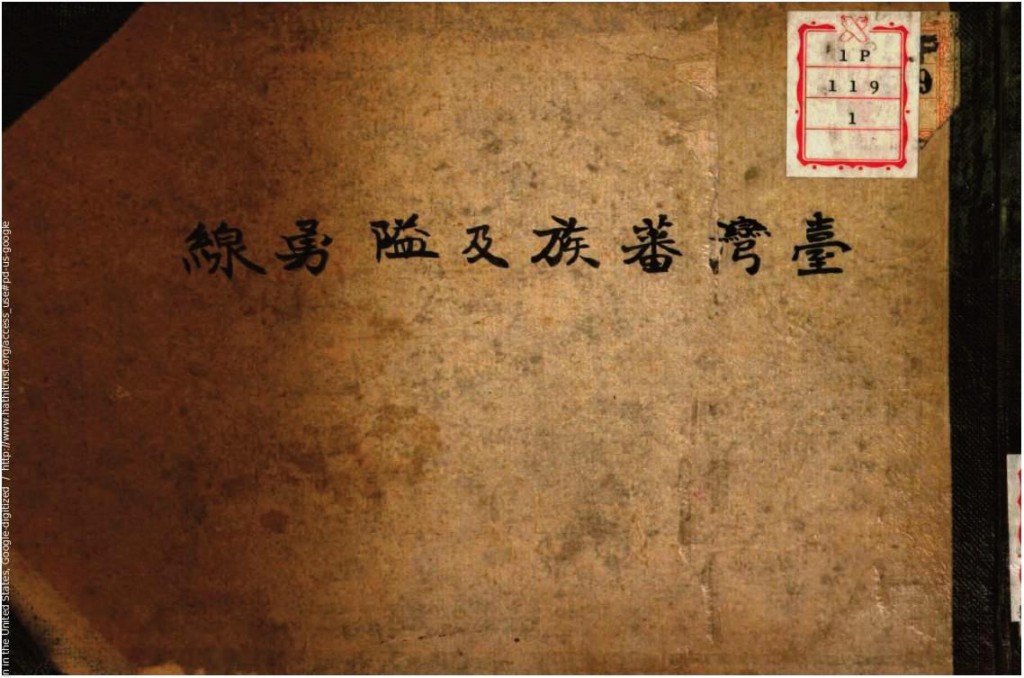

Here are some images from 1910 and 1912 photo albums commemorating the movement of the “guardline” against Taiwan Indigenous Peoples, mostly in northern Taiwan. The former was published by the Bureau of Aborigine Affairs; the latter by a Taiwan-based photographer/publisher. They follow similar formats: the ethnic groups are introduced as timeless “types” in the first half of the album, then the second half of the album illustrates troop movements against the people so described. It is likely that the postcards representing field maneuvers were drawn from these albums, which were published soon after the events described. On the other hand, the reverse is probably true for the “ethnographic” part of the albums. The photos used to display “types” are seven to ten years older than the albums, and postcards were also likely published before the albums.

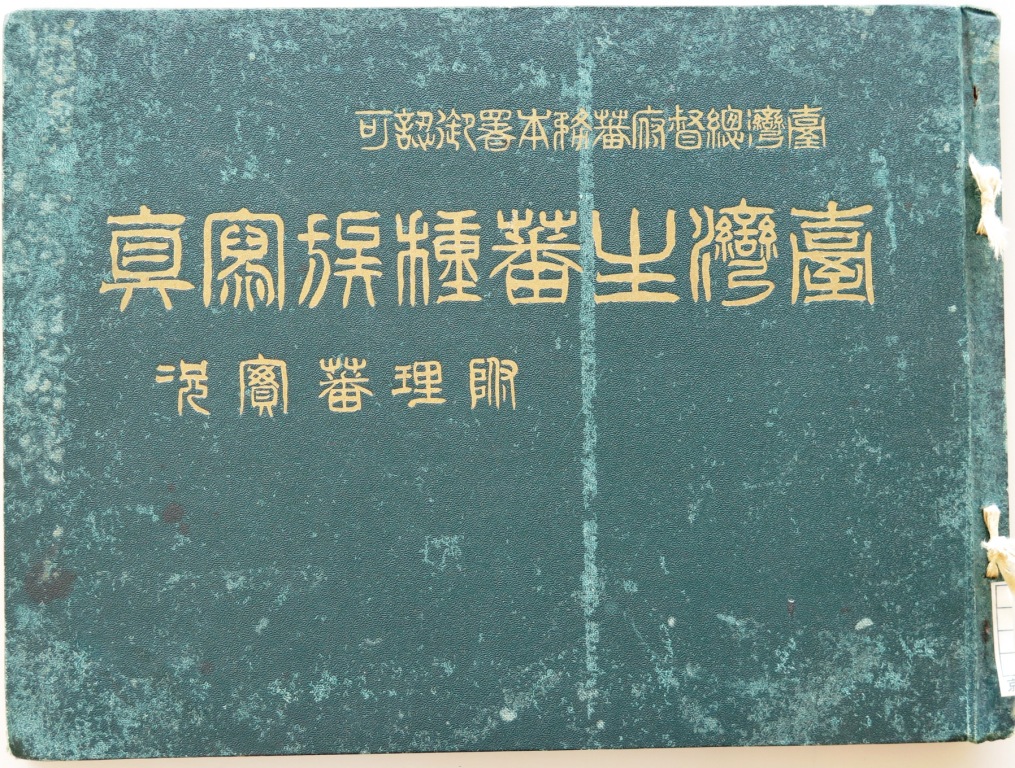

Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

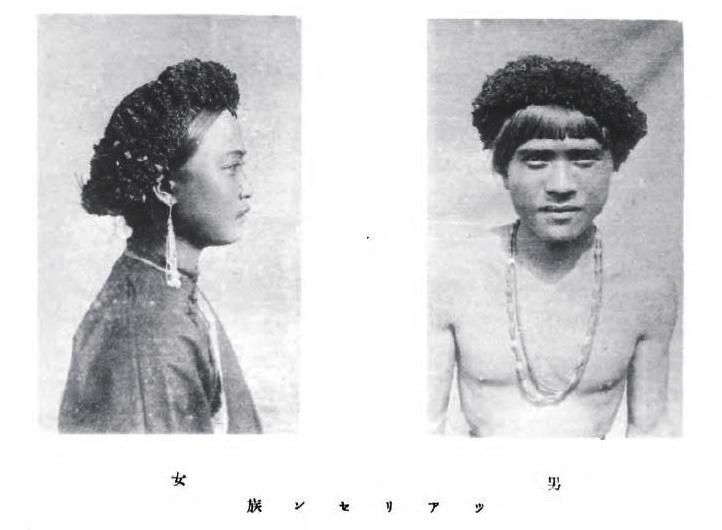

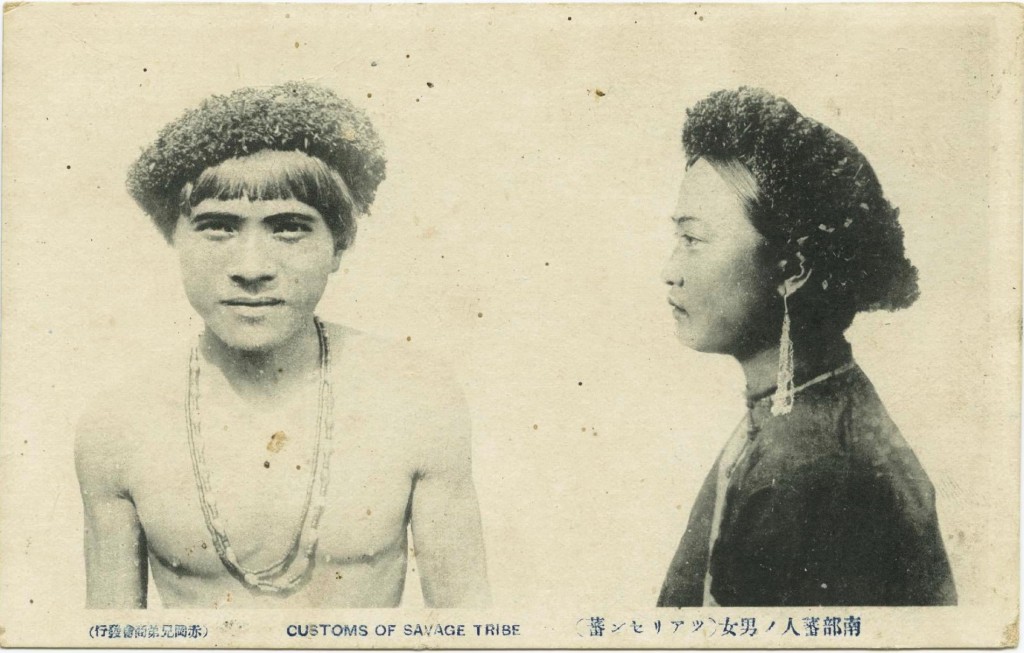

“Native Type” From Official Picture Album: “Man, Woman, Tsarisen Tribe” Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org).

Privately produced picture postcard, Akaoka Kyodai, co. Note that the image is mirrored from the photo album version; the caption is about the same. East Asia Image Collection

Privately produced picture postcard, Akaoka Kyodai, co. Note that the image is mirrored from the photo album version; the caption is about the same. East Asia Image Collection

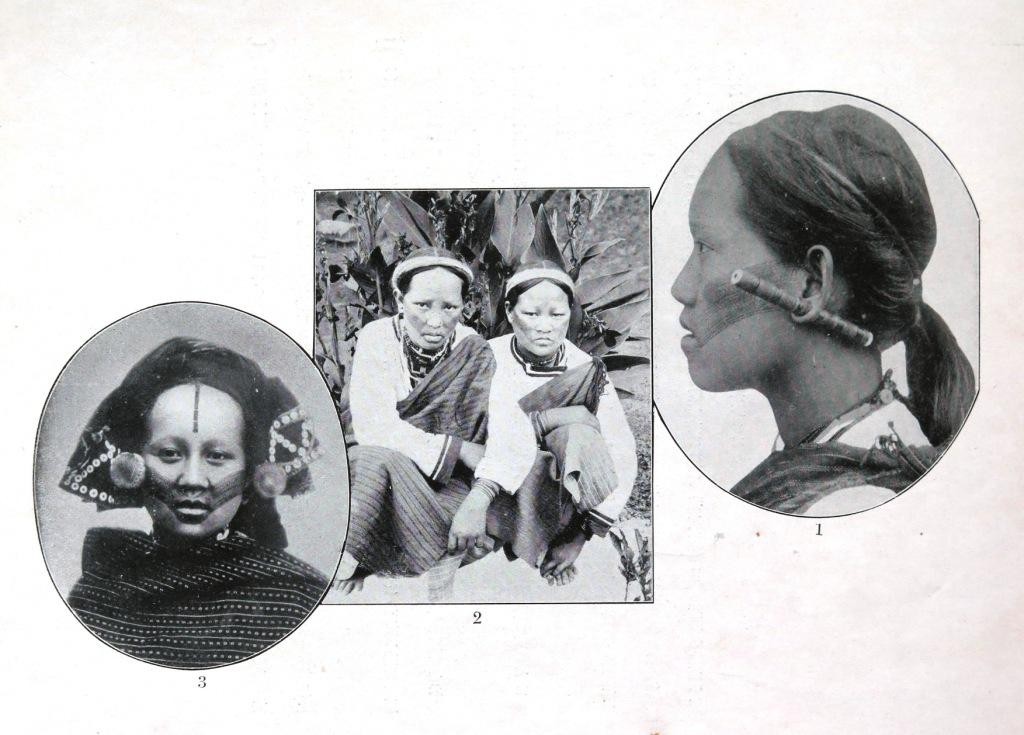

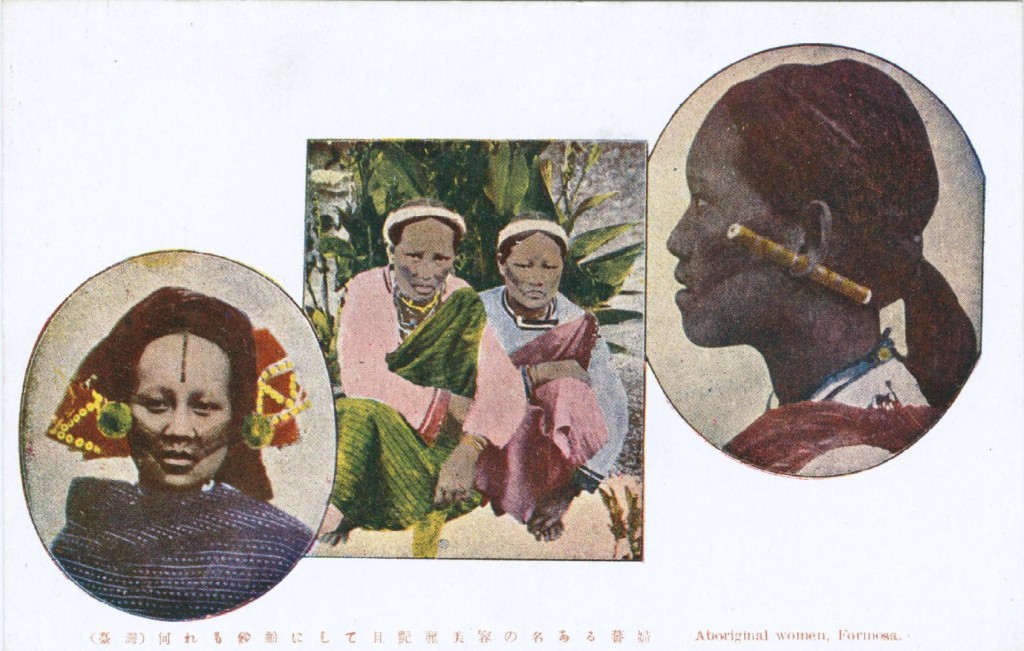

“Native Types” from the 1912 commemorative album Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

“Native Types” from the 1912 commemorative album Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

Picture Postcard of “Native Types” from East Asia Image Collections

Picture Postcard of “Native Types” from East Asia Image Collections

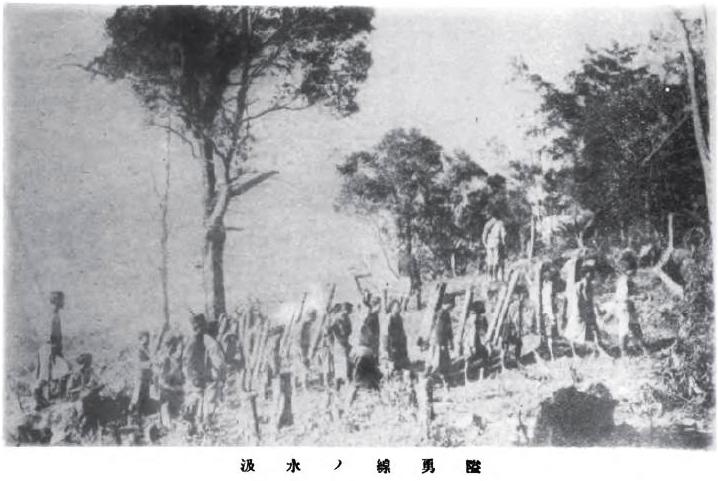

Mountain warfare: From official photo album: “The Guardline and Water-carrying” Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

Mountain warfare: From official photo album: “The Guardline and Water-carrying” Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

Picture Postcard of mountain warfare, early 1910s. “Savages Carrying Provisions” East Asia Image Collection.

Picture Postcard of mountain warfare, early 1910s. “Savages Carrying Provisions” East Asia Image Collection.

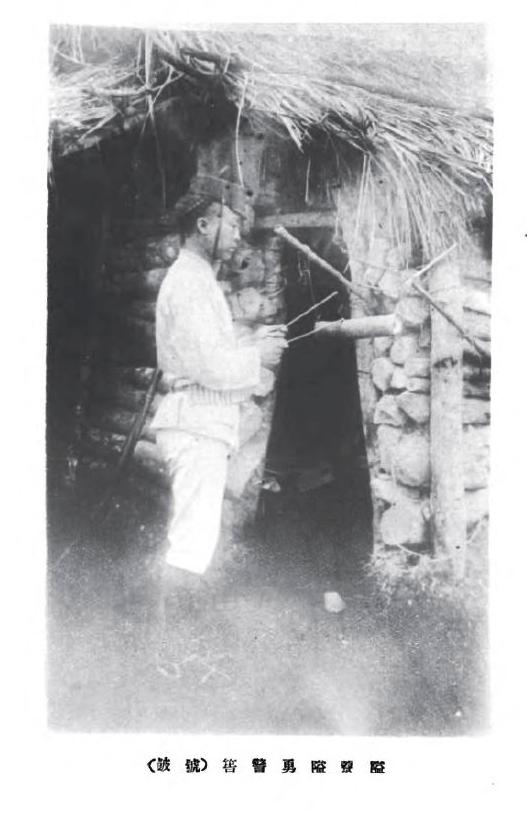

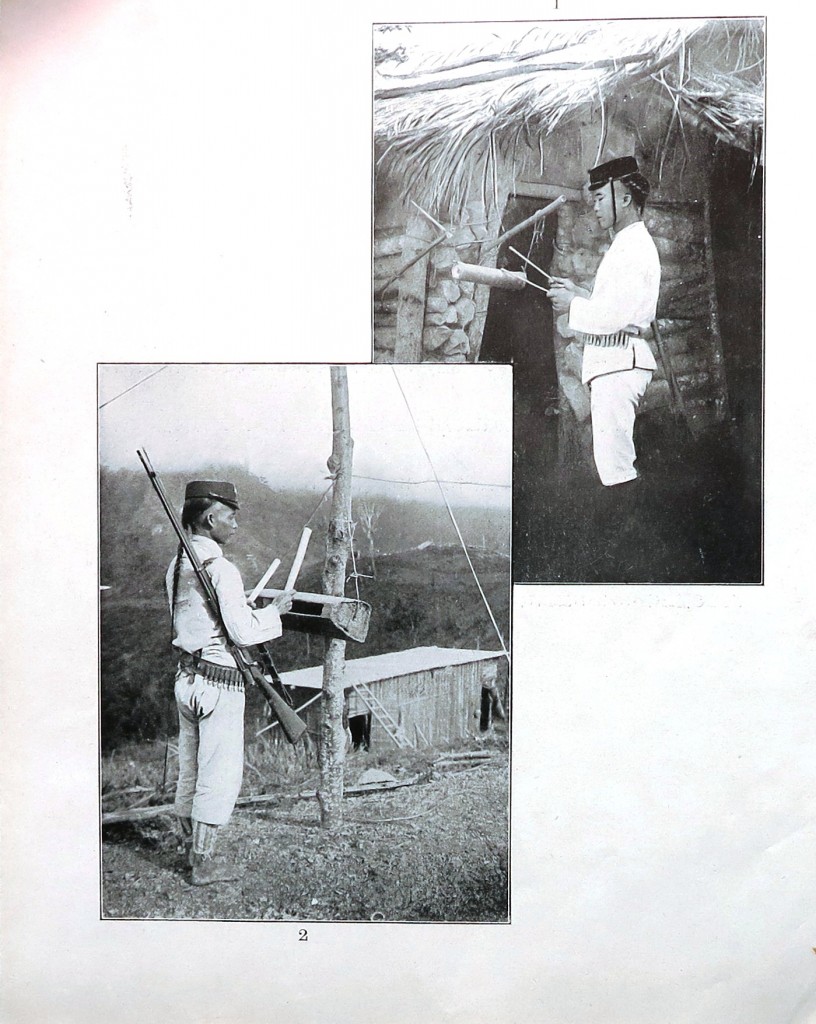

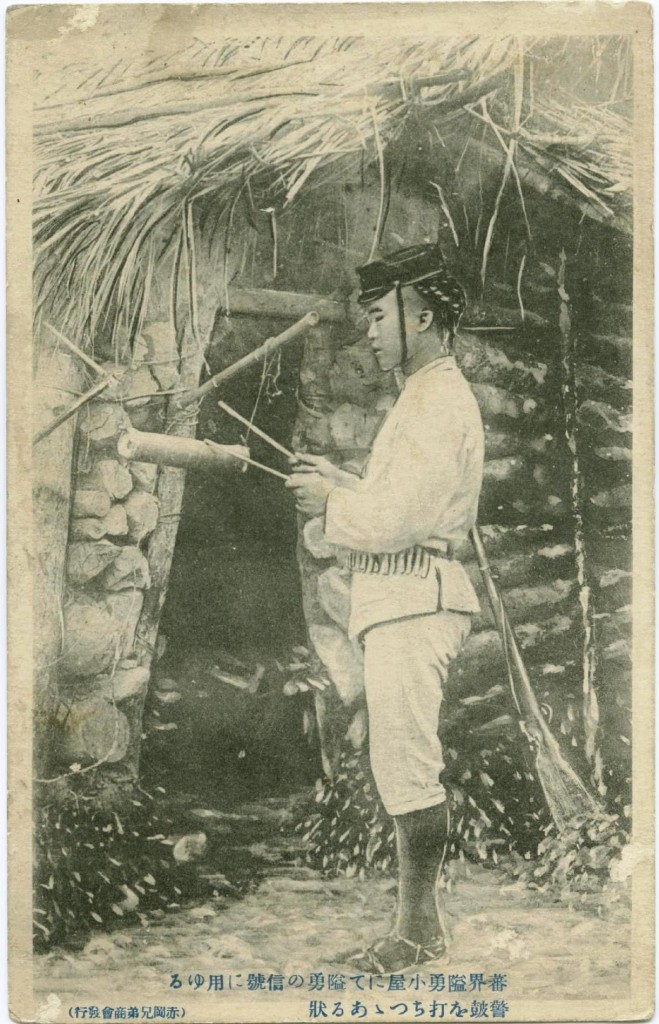

“The Guardline and The Warning Signal Drums” Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

“The Guardline and The Warning Signal Drums” Taiwan Indigenous Peoples and the Guardline (Bureau of Aborigine Affairs, 1910) (Hathi Trust.org)

Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

Taiwan Indigenous Tribes Picture Book with an Appendix on Aborigine Affairs. (Taipei, Narita Photography, 1912).

The long caption on the facing page of this book explains how image one illustrates an early method of guardline communication and details the construction of the bamboo sounding tubes; image two reveals a more recent method: the guards have taken an abandoned Atayal loom frame and converted it into a communication device. The image is a mirror image of the photo from the 1910 album.

“An Auxiliary in an Aborigine Territory Guardline Hut uses the Warning Drum to Make Signals.” This picture postcard reproduces an image found in both the 1910 and 1912 commemorative albums, but adds little new information. Produced by the Akaoka Kyodai company. East Asia Image Collection.

“An Auxiliary in an Aborigine Territory Guardline Hut uses the Warning Drum to Make Signals.” This picture postcard reproduces an image found in both the 1910 and 1912 commemorative albums, but adds little new information. Produced by the Akaoka Kyodai company. East Asia Image Collection.

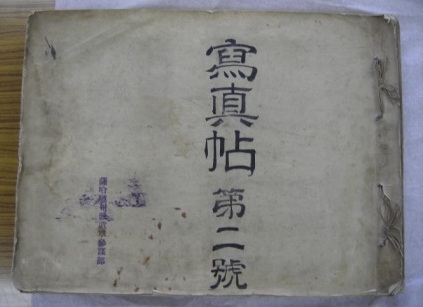

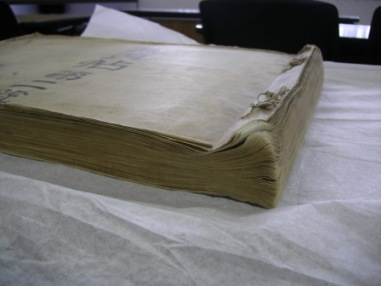

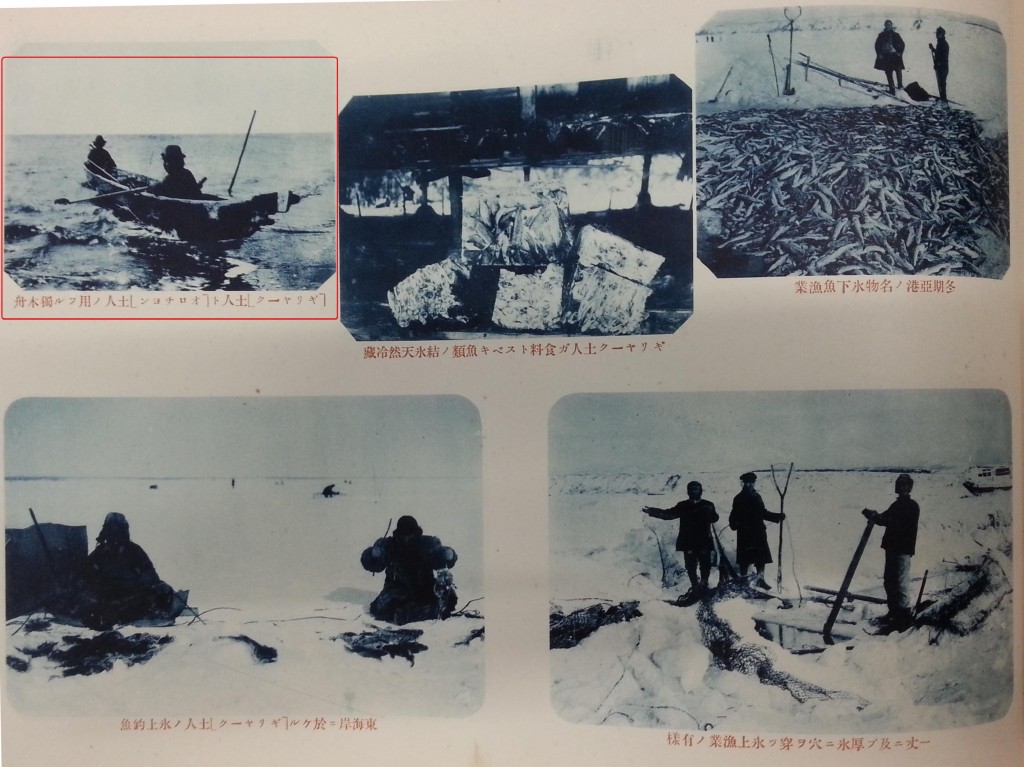

A decade after the rash of Taiwan punitive expedition photo albums appeared, the “Siberian Expedition” of 1919-1922, which included the occupation of northern Karafuto (a Russian territory), became a similar occasion for official and commercial photo album and postcard production. There are eight expedition photo albums housed at the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団) in Tokyo, Japan. They contain hundreds of prints and captions of photos taken during the Japanese occupation of Northern Karafuto, probably between 1920 and 1922. These albums are about as close as one can get to a “primary source” regarding Japanese imperial postcards, because most of the original material has been lost or destroyed, or it is off-limits to researchers for proprietary reasons. Here the format of the albums:

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

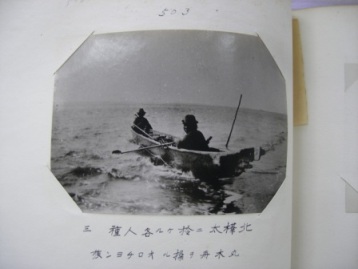

This print was captioned: “The Native Races of Northern Karafuto Part III: Orochen Piloting a Log Boat” (北樺太に於ける各人種 三 丸木丹を操るオロチョン族):

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

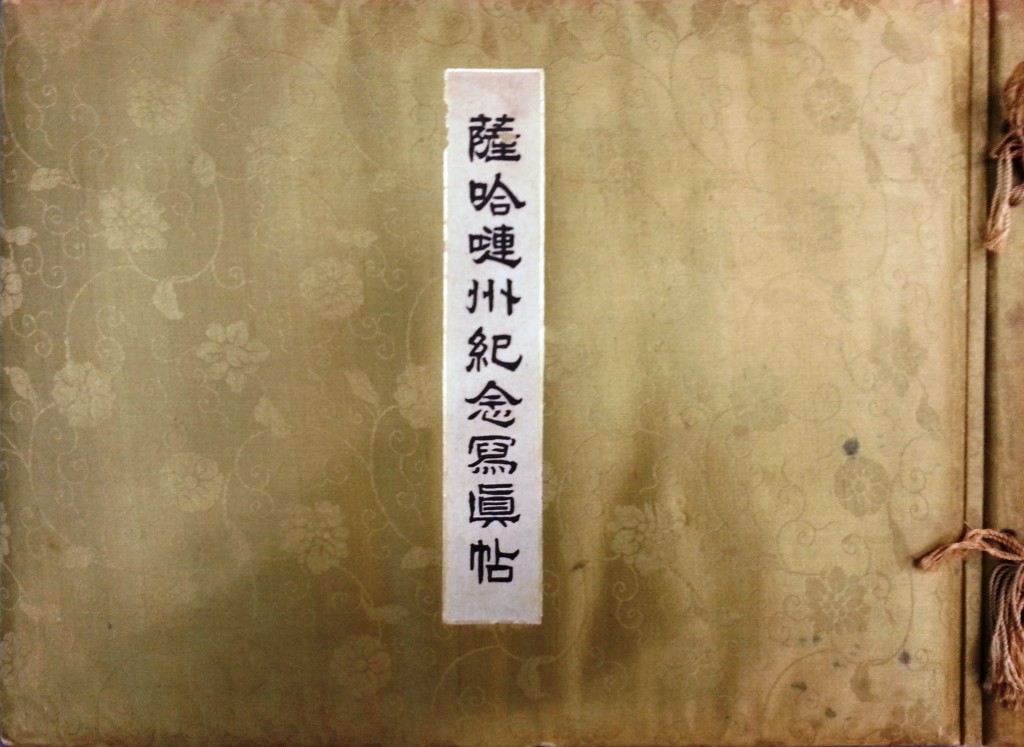

This photo was reprinted in at least two lavishly bound, collotype print, photo albums: “Sakhalin Province Commemorative Photo Album (1923)” (野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会 http://srcmaterials-hokudai.jp/photolist_si.php?photo=si07) and “Northern Lights: The Mitsubishi Dispatch Station in Sakhalin Ako (1924)” (野坂保雄、 『極光』 薩哈嗹州亜港:三菱合資会社北樺太出張所 http://srcmaterials-hokudai.jp/photolist_si.php?photo=si06). Here’s the 1923 album and the page with the “Orochen Boat” photograph:

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

In the 1923 album, the caption has been changed to: “Single-Log Boats used by the Gilyak and Orochen Natives.” The photo is part 3 in a series of four photos about the native races of northern Sakhalin in the unpublished scrapbooks, but the published album re-captions the picture to emphasize the boat, pulling it out of the “native races” series.

The Sakhalin Expeditionary Force Command that organized the scrapbooks also published a 12-postcard set, probably in the early 1920s as well.

The “Orochen Boat” image appeared in this set with a caption very similar to the the military album (though it is no longer labeled as part of a 4-image “native race” series):

The “Orochen Boat” image appeared in this set with a caption very similar to the the military album (though it is no longer labeled as part of a 4-image “native race” series):

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College

East Asia Image Collection, Lafayette College

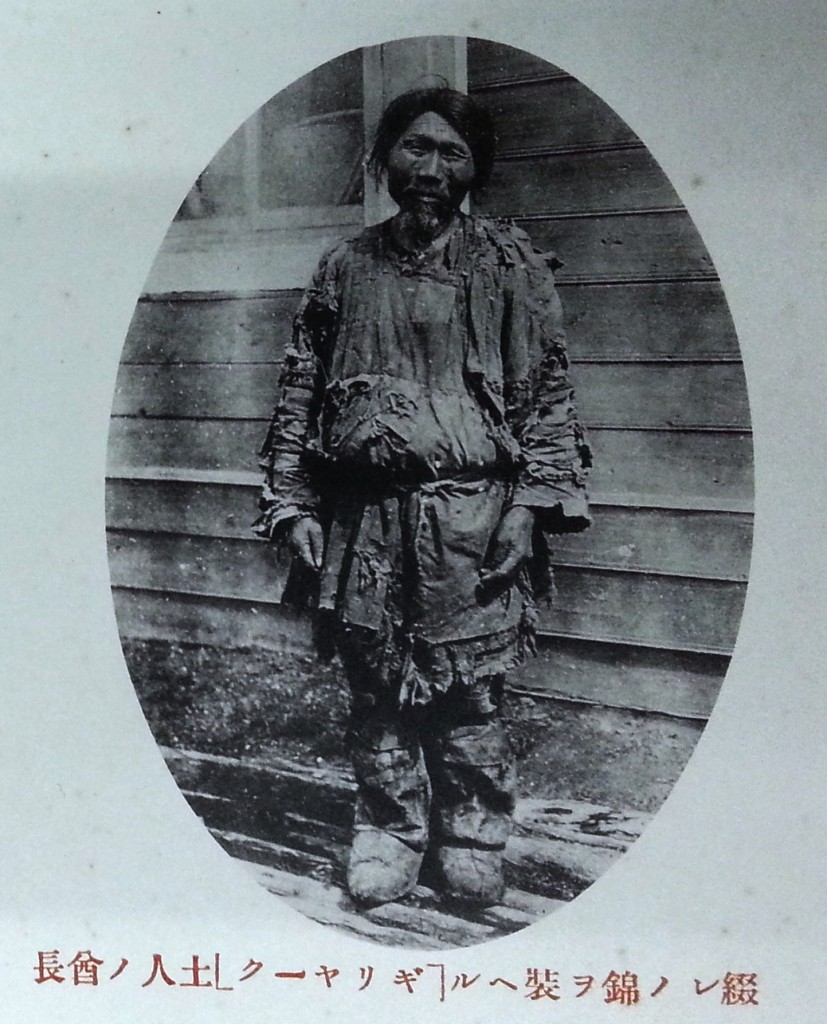

While information was lost in the transition from military scrapbook to album in the above image, because we no longer know if the people are Orochen or Gilyak, in other cases, album editors added important information to photos that were quite sparely captioned in the scrapbooks. For example, the scrapbook image for Part IV in the “Native Race” series is simply captioned “A Gilyak Man.”

“Native Races of Northern Karafuto Part IV: A Gilyak Man”

“Native Races of Northern Karafuto Part IV: A Gilyak Man”

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

“Wearing his Tattered Finery: A Gilyak Native Headman”

If indeed the pictured man was a “headman,” that would mean he served an intermediary role, most likely, between Japanese forces and local laborers. This piece of important information is missing from the scrapbook album version. In the next image, the scrapbook is also less informative than the commercially published album:

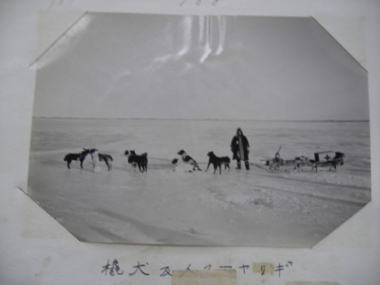

“A Gilyak and his Dog Sled”

“A Gilyak and his Dog Sled”

Courtesy of the Japan Camera Industry Institute (一般財団法人日本カメラ財団)

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

野坂保雄、『薩哈嗹州紀念冩眞帖』 薩哈嗹州亜港:薩哈嗹州記念写真帖刊行会, 1923 p. 32

“Gilyak Native Dog Sled in the Employ of Our Military”

The fact noted in the caption, that this Gilyak man was in the employ of the Japanese expeditionary forces, seems important, but is not included in the album version. In the official postcard version, however, we find other information not included in the album that is very useful to historians: the location of the scene.

East Asia Image Collection

East Asia Image Collection

“A Gilyak and his Dog Sled on the Ice of Northern Karafuto’s east coast ‘Chiyaio’ Bay”

As we can see from the above examples, picture postcards, published photo albums and unpublished archival sources can caption the same image differently, without necessarily contradicting the other sources. In these cases, we learn more about the image when all three sources are consulted–none can be left out.

In 1925, the year the Japanese forces finally left northern Sakhalin, The Government of Karafuto (on the southern part of the island) produced a photo album similar in format to the 1923 and 1924 albums referred to above:

樺太庁(編)、 『樺太冩眞帖』, 1925.

樺太庁(編)、 『樺太冩眞帖』, 1925.

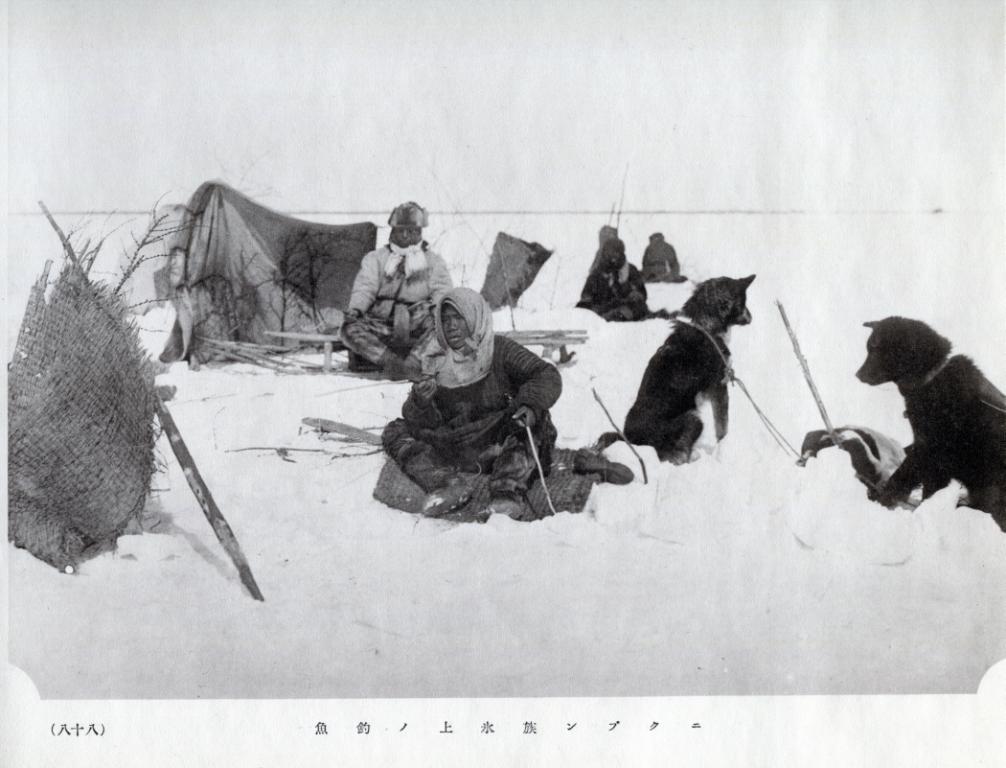

As was the case with the previous albums, postcard producers used images from this official source and altered the contents. Here’s the album version of an ice-fisherman (a common postcard theme from Karafuto):

樺太庁(編)、 『樺太冩眞帖』, 1925, p. 88: “Nikubun Fishing on the Ice”

樺太庁(編)、 『樺太冩眞帖』, 1925, p. 88: “Nikubun Fishing on the Ice”

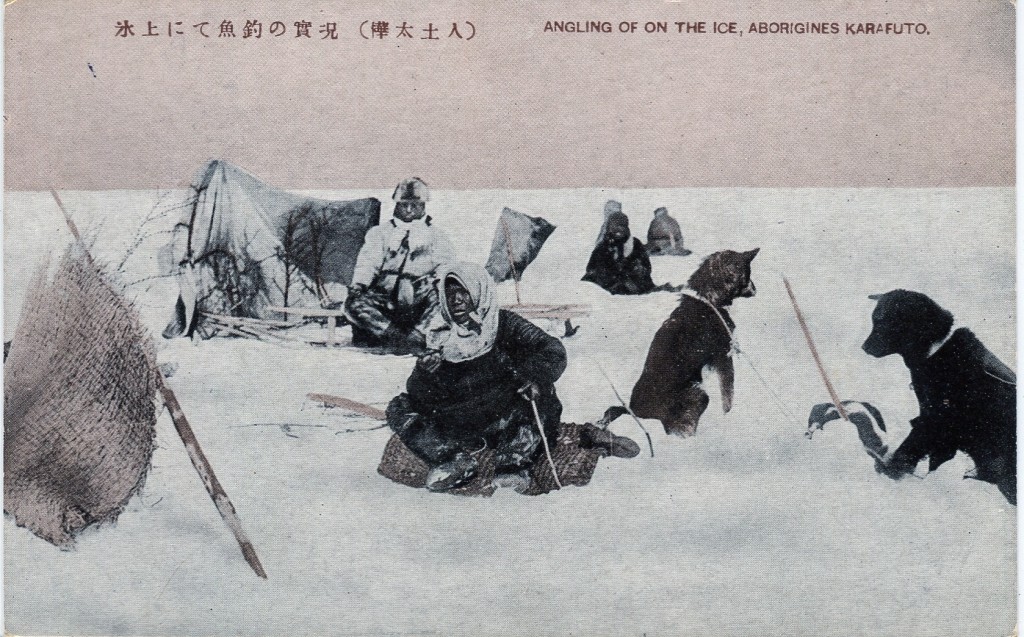

This postcard version adds a layer of lithographic color, but omits the name of the ethnic group depicted in the album photo:

East Asia Image Collection: “Karafuto Native: Ice Fishing Conditions”

East Asia Image Collection: “Karafuto Native: Ice Fishing Conditions”

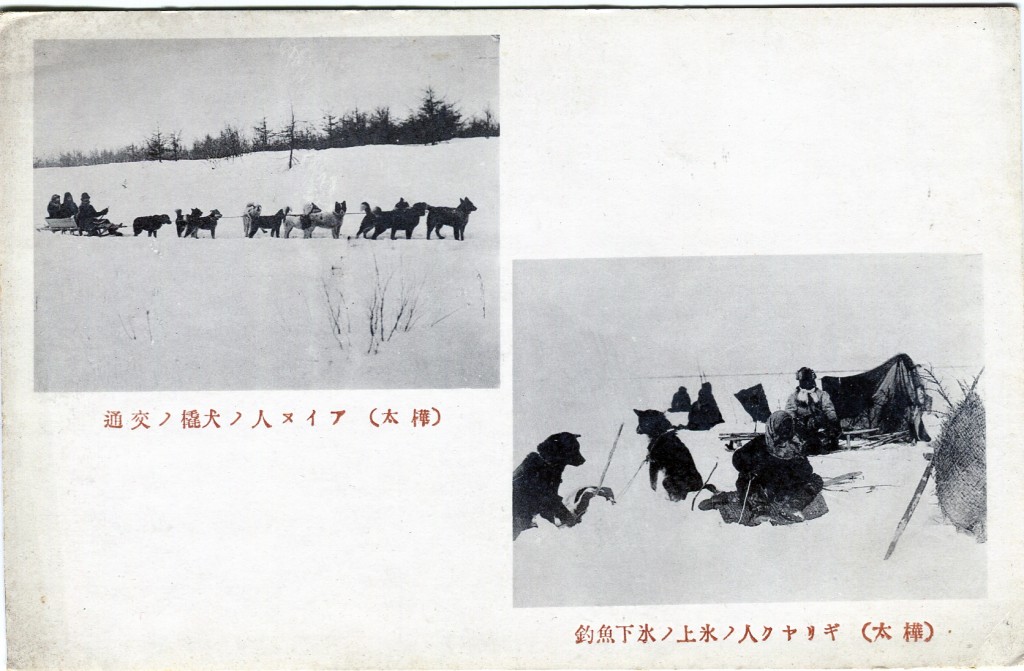

Lastly, this other postcard combines two images from Karafuto, each from a different ethnic group. The dog sled is Ainu, while the picture labeled “Nikubun” in the album (the official ethnonym for “Gilyak”) is changed back to the Japanese vernacular “ギリヤク”(Gilyak is the Russian word for the Nivkh [Nikubun] people). Moreover, as is common with picture postcard images, we find a mirror-image print of the negative on this postcard, which puts the dog to the left of the foregrounded fisherman, instead of on the right (as in the above two examples:

Courtesy of Toshihiko Kishi

Courtesy of Toshihiko Kishi

In sum, as I hope these examples have shown, a thorough investigation of imperial postcards perforce involves a study of nearly all military and official photography from the period 1900-1945. Picture-postcard research, carried out in this manner, is not a narrow overly-specialized field of study, but rather a window into the extremely large body of visual material left over from a far-flung empire that seems to have had no shortage of photographers.

back [1] Park, Mijeoung 朴美貞. Teikoku shihai to Chosen hyosho–Chosen shashin ehagaki to teiten nyusensaku ni miru shokuminchi imeeji no denpa 帝国支配と朝鮮表象――朝鮮写真絵葉書と帝展入選作にみる植民地イメージの伝播. Kokusai Nihon bunka kenkyu sentaa 国際日本文化研究センター, 2014.

back [2] 向後恵里子, ‘Teishinshō hakkō Nichiro seneki kinen ehagaki: sono jissō to igi’ [Ministry of Telegraphs and Posts Commemorative Battle Postcards of the Russo-Japanese War: On their Empirical Status and Significance] 逓信省発行日露戦役紀念絵葉書―その実相と意義―. Bijutsushi kenkyū 美術史研究 41 (2003): 103-142.

For a major exhibit titled ‘Rainbow and Dragonfly,’ held from Septemember 2014 through March 2015 at the National Taiwan Museum in Taipei, a large billboard greets visitors and passersby with four distinct examples of Atayal textile manufacture, of varied pattern and age, all dominated by the color red.

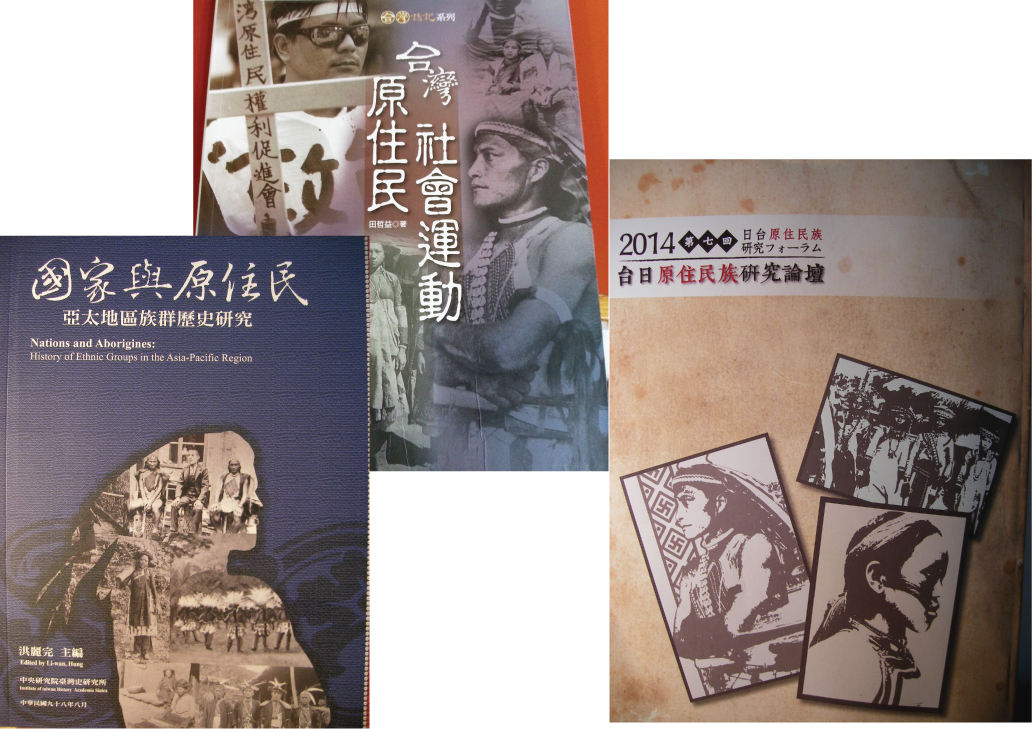

These three recent book covers all feature graphics based on a photograph that first appeared in the June, 1935, issue of Riban no tomo 「理蕃の友」(page 3). From left to right, they were published in 2009, 2010, and 2014 [1]. The third publication is a collection of conference papers from the 7th Japan-Taiwan Forum for Research on Indigenous Peoples held at Chengchi University, Taipei, on October 12, 2014 (国立政治大学に開催さらた 2014第七回日台原住民族研究フォーラム).

These three recent book covers all feature graphics based on a photograph that first appeared in the June, 1935, issue of Riban no tomo 「理蕃の友」(page 3). From left to right, they were published in 2009, 2010, and 2014 [1]. The third publication is a collection of conference papers from the 7th Japan-Taiwan Forum for Research on Indigenous Peoples held at Chengchi University, Taipei, on October 12, 2014 (国立政治大学に開催さらた 2014第七回日台原住民族研究フォーラム).

This image was the backdrop to all of the panels at Chengchi University:

For a full day, I stared at this image and wondered where it came from, and what its life history has been as a symbol of Tsou/Zou/鄒 peoples, or all Taiwan Indigenous Peoples.

For a full day, I stared at this image and wondered where it came from, and what its life history has been as a symbol of Tsou/Zou/鄒 peoples, or all Taiwan Indigenous Peoples.

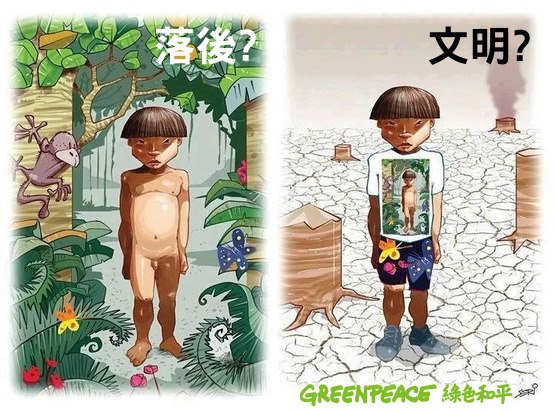

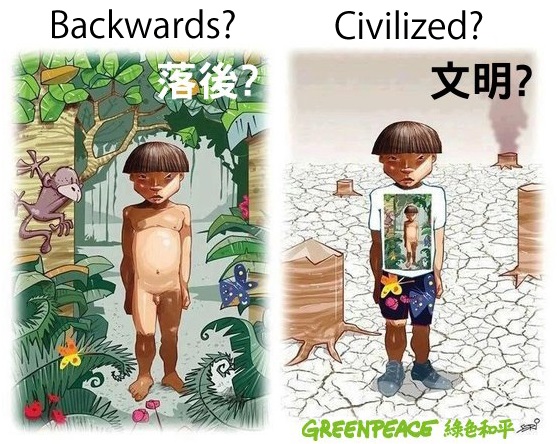

This image below just about sums up the concept and research topic I am developing, which I call “Indigenous Modernity.” It was posted to the Taiwan Greenpeace site on December 17, 2012 (it is buried deep within their photo album; I saw it on a repost on anthropologist Scott Simon’s FB page on October 9, 2014):

With translation:

With translation: Can these two ideals exist separately? Can a fully fashion-conscious, technologically sophisticated, culturally competent modern individual be conceivable without some trapping of neo-primitivist artwork, photography, or decorative bric-a-brac thrown in for good measure? Conversely, can an easily comprehensible two-dimensional image of an untouched, uncomplicated, “natural and uncorrupted native” exist separately from historically developed commercial-academic-technological inscription machines that make such images not only possible, but emotionally appealing? Which comes first, the Chicken or the Egg? Continue reading

Can these two ideals exist separately? Can a fully fashion-conscious, technologically sophisticated, culturally competent modern individual be conceivable without some trapping of neo-primitivist artwork, photography, or decorative bric-a-brac thrown in for good measure? Conversely, can an easily comprehensible two-dimensional image of an untouched, uncomplicated, “natural and uncorrupted native” exist separately from historically developed commercial-academic-technological inscription machines that make such images not only possible, but emotionally appealing? Which comes first, the Chicken or the Egg? Continue reading

Overview

If you work with Japanese picture postcards as historical source material, you have probably noticed that most surviving cards lack postmarks and other temporal indicators. This post provides a guide to estimating the age of these revealing artifacts, based on printing conventions that conformed to international and Japanese postal regulations. This post also provides several examples and explanations of Japanese postmarks. Continue reading

Herbert Bix’s much discussed Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2000) and the Hollywood film Emperor (2012) provide two examples of how middle-brow America has continued to put the Showa Emperor (Hirohito) at the center of events in World War Two, despite decades of revisionist scholarship that has sought to either demote him to a constitutional monarch, or broaden the base of explanatory devices for understanding Japanese wartime ideology and mobilization.

In Bix’s account, based on decades of research in Japanese-language source material, the Emperor was an active military planner and eager participant in the war. In the cinematic treatment of Japan’s “surrender,” Emperor, Japan is said to have a “2000-year old” culture that is deeply efficacious, homogenous, and pivots around the imperial line. This imperial culture, intones a “native informant” played by Nishida Toshiyuki as “General Kajima,” enabled “the Japanese” to display an unwavering sense of duty, while losing their humanity, over the course of the war. Continue reading

This series of nine Japanese postcard images, titled “Shanghai Front 1937,” illustrates the early stages of Japanese operations in and around Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War which began with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident on July 7, 1937.[1] The Japanese maintained a peacetime garrison in the major international port of Shanghai of 5,000 marines, which the Chinese army fought into a confined perimeter during the first weeks of hostilities.[2] The fighting rapidly escalated as both sides ordered tens of thousands of reinforcements into the city because of its strategic and psychological importance. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek eventually committed over 500,000 soldiers (including several of his elite German-trained divisions) while Japanese forces would swell to about 200,000 soldiers.[3] The following analyses provide explanations of the photographs and regard them as part of the larger military campaign, assuming they were produced as Japanese wartime propaganda.

[ip0167] (8/13/1937) Caption: “Battle line of Shanghai 1937 Japanese troops dared to land in the face of Chinese fire” (昭和十二年支那事変 上海戦線 敵前上陸敢行丸〇〇部隊の勇姿) Continue reading

[ip0167] (8/13/1937) Caption: “Battle line of Shanghai 1937 Japanese troops dared to land in the face of Chinese fire” (昭和十二年支那事変 上海戦線 敵前上陸敢行丸〇〇部隊の勇姿) Continue reading