Mental Health and its Treatment for Justice Involved Women

Since the 1980s, the amount of women entering the criminal justice system has dramatically increased. One key cause of this is the War on Drugs, which meant that more women were arrested and convicted of drug offences than before. For information on the drug addiction issues of women in the system, please take a look at the ‘Drug Addiction’ page of this site, however on this page I focus on the mental health issues of women in the system, the treatment they are currently being provided and proposed improvements to these treatment programs.

Throughout this blog, I will identify how mental health treatment is woefully lacking in jails and prisons throughout the US. This affects all incarcerated people. However, the rising number of incarcerated women, and the high percentage of those women who enter the system with mental health issues, means that this is a problem that disproportionately affects women. I will also identify how there is limited access to mental health treatment on the outside of prison for low-income communities where people may not have health insurance or the funds to afford treatment. This means that women coming into the criminal justice system from low-income communities are even more likely to need the treatment that jails and prisons struggle to provide. Before I delve into the current mental health treatment available inside prisons and jails, and suggestions for how it should be improved, it is important to understand the prevalence of mental health problems among the population of incarcerated women.

Profile of women in the US criminal justice system (National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women):

- Women in jails and prisons report high rates of mental health problems such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse.

- About 1 in 3 justice involved women meet criteria for current PTSD, with 1 in 2 meeting criteria for lifetime PTSD.

- A national survey found that 55% of male adults in state prisons exhibited mental health problems as compared to 73% of women prisoners.

- A multisite study of jail detainees found that 14.5% of men and 31.0% of women had current serious mental disorders.

- There is some evidence that women with mental health problems may be more likely to commit violent crimes.

- Women with mental disorders also have higher infraction rates than non-mentally ill females while incarcerated.

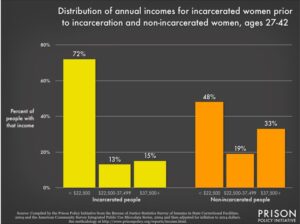

Furthermore statistics from the Prison Policy Initiative that these women entering the criminal justice system are also from low income backgrounds:

- “The American prison system is bursting at the seams with people who have been shut out of the economy and who had neither a quality education nor access to good jobs.”

- “incarcerated people had a median annual income of $19,185 prior to their incarceration, which is 41% less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages.”

- Specifically, women from all ethnic backgrounds earned less than their male counterparts, whether incarcerated or not:

For more information, please click here.

Current Treatment – Availability

Most data points to the fact that mental health treatment in prisons and jails is extremely limited, and that most inmates do not get the care they need. A study that focused on the mental health of inmates and its treatment, found that “a substantial portion of the prison population is not receiving treatment for mental health conditions. This treatment discontinuity has the potential to affect both recidivism and health care costs on release from prison.” (Gonzalez and Connel.) This is despite the fact that, as discussed above, 55% of male state prisoners and 73% of female state prisoners exhibit mental health problems. An NPR article entitled “Most Inmates With Mental Illness Still Wait For Decent Care” explored the story of a prison inmate in Illinois who spent 22 to 24 hours a day in a small cell, even though he had been diagnosed with depression, schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. In his interview, the inmate claimed that, despite the diagnosis of his mental disorders, he was treated by staff as if he just had behavioral problems:

“Even if they would label us schizophrenic or bipolar, we would still be considered behavioral problems. So the only best thing for them to do was keep us isolated. Or they heavily medicate you.”

Access to mental health treatment in prison varies from state-to-state, county-to-county and facility-to-facility. A 2006 study entitled “Availability of Behavioral Health Treatment for Women in Prison” conducted by New Jersey and New York based professionals found that “data on mental health spending by 16 state prison systems indicated that these states spent, on average, 17 percent of their correctional health care budget on mental health services, with a range from 5 percent (Minnesota) to 43 percent (Michigan). Mental health spending represented roughly 18 percent of the correctional health care budget for New Jersey prisons in 2002.” (Blitz, et al., 356.)

Although this study found that, in the early 2000s, some states dedicated a sizable portion of their correctional health care budget to mental health treatment, the reality of the availability of treatment in correctional facilities today is unclear. Despite the fact that some data identifies that mental health treatment in prisons and jails is severely lacking, the likelihood to gain access to mental health treatment in prison is much higher than on the outside for individuals who come from low-income backgrounds. As previously discussed, most people entering into the criminal justice system come from low-income and disadvantaged backgrounds. Where access to mental health treatment is difficult to get on the outside, it is ‘technically’ a constitutional right on the inside. The barriers to accessing treatment outside of prison are mostly due to “a lack of health insurance, organizational complexities, and society’s attitudes.” Whereas in prison, “ability to gain access to treatment is likely to be improved…. in part because individuals in prison have a constitutional right to medical and mental health treatment and in part because financial, organizational, and transportation barriers in the community are considerably less significant.”(Blitz, et al., 356.)

Although barriers to mental health care in prisons affect all incarcerated people, the fact that more women enter the system with mental health issues means that these barriers disproportionately affect women. Mental health treatment is difficult to access in low-income communities so that, “for many women, prison may be the first circumstance in which they have been able to access resources, in particular substance abuse treatment, reproductive and physical, dental and vision health care, and mental health counseling.”(Blitz, et al., 356.) However despite this easier access to healthcare inside, “service delivery in prison remains woefully inadequate and sometimes deadly.” (Zaitzow, 8.) Women, especially those from low-income communities, are essentially set up for failure the moment they enter the facility.

Current Treatment – Psychotropic Control

One identifiable form of mental health treatment that is used in prisons is the prescribing of psychotropic drugs. Psychotropic drugs are drugs that have a “biochemical effect on the brain and the nervous system” (Hatch and Bradley, 225) and are prescribed to help illnesses like depression or schizophrenia. Prozac, for example, is a commonly prescribed psychotropic drug. These drugs can have severe negative effects on individuals if they are not prescribed sensibly because they can “change thought, mood, and social behavior. Even when they are prescribed and used in ways consistent with sound psychiatric practice, psychotropic medications have been associated with suicide, homicide, and other forms of interpersonal violence.” (Hatch and Bradley, 225.) This medication, when the wrong doses are administered or are mixed with other drugs, can “impair the functioning of the patient,” as well as produce orthe negative effects such as an “altered sleep pattern, tardive dyskinesia, muscular rigidity, constipation, sexual dysfunction, seizures, depression, increased risk of suicide, dry mouth, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.” (Zaitzow, 13.)

Women are disproportionately affected by the prescription of psychotropic drugs in prison, simply because “women prisoners are more likely to receive psychotropics during incarceration” (Hatch and Bradley, 235) as “many female inmates have stated that psychotropic medications are widely distributed to inmates by correctional personnel.” (Zaitzow, 14.) There is evidence that shows psychotropic drugs are administered to inmates as a form of coercion and sedation, even when the drug is not medically required. Although it is difficult for researchers to discern how often this happens, as “it is unlikely that institutions will reveal the purposeful drugging of female inmates as a means of coercion….and few whistle-blowers have come forward” (Zaitzow, 11) some sources express concern that these drugs “are sometimes used improperly to control and sedate inmates rather than as medication for psychiatric conditions.” (Zaitzow, 11.)

Barbara Zaitzow, a professor of Government & Justice Studies at Appalachian State University, North Carolina, conducted a study called “Psychotropic Control of Women Prisoners:The Perpetuation of Abuse of Imprisoned Women,” for the Justice Policy Journal. In this study, Zaitzow identified examples of women being coerced into taking psychotropic drugs unnecessarily:

- “Women in a California prison reported that they were pressured into taking psychotropic medication while detained in jail before being tried. A number of women prisoners stated that drugs were often ordered by people – including correctional officers – who are not qualified to diagnose the psychiatric conditions for which the medications are appropriate treatment and who are not legally permitted to prescribe medications.Some of the women in the study reported that the amount and mixture of drugs made it difficult for them to comprehend what was happening and adversely affected their ability to function during their trial.”

- “Lawyers in California, Illinois and Pennsylvania have also told Amnesty International that they have had clients who were so heavily drugged the lawyers had considerable difficulty communicating with them.”

To read more on this issue, and to see Zaitzow’s own research and references, click here.

This practice exacerbates the fact that many incarcerated women, for the first time, are able to access mental health treatment in prison, but that this doesn’t mean the treatment is correct, humane or allows the woman to have control over her own body. This practice seems to be able to continue because firstly, it is unclear how often this practice occurs and secondly, the state asserts it has the right to “[maintain] social control and power within prisons by forcing potentially dangerous, legally incompetent, or mentally ill prisoners to take psychotropics which it can do if the prisoner is classified as dangerous and if the forced drugging is in the best medical interest of the prisoner.” (Hatch and Bradley, 234.) Furthermore, society’s belief that prisons ‘deserve’ whatever they get in prisons and jails because of their crime allows people to turn a blind eye toward what is really happening to incarcerated people, especially incarcerated women from low-income backgrounds.

Proposed treatment – what are the best approaches for treating incarcerated women?

Using what I have learned through my research, and by reading through proposed approaches to mental health treatment in prisons and jails in general, and specifically for women, I have come up with five key points that should be addressed by correctional facilities providing treatment for incarcerated women. In particular, I have drawn from the proposed approaches from the following sources:

- Anthony Ryan Hatch and Kym Bradley, “Prisons Matter: Psychotropics and the Trope of Silence in Technocorrections” in Mattering: Feminism, Science and Materialism, (NYU Press, 2016).

- Heather Stringer, “Improving Mental Health for Inmates,” American Psychological Association, 50, (March 2019).

- World Health Organization, “Mental Health and Prisons.”

From my research, it is clear to me that women with serious mental health issues should not be in jails or prisons. Small cells, large populations of other women, disconnect from friends and family (especially dependent children, as many incarcerated women are mothers), are not environments that promote positive mental health. I believe all women entering the criminal justice system should be sensitively screened for mental health problems. By that, I mean, each woman should be allocated time with a trained doctor so that any mental health problems can be accurately diagnosed. Those with severe mental health issues, such that they pose a danger to themselves or others, should be sent to a mental health treatment facility before continuing their sentence in a jail or prison. Of course, it is difficult to discern who should receive this specific treatment, but I believe this will help relieve some of the pressure jails and prisons are under to provide treatment for large groups of women with varying mental health problems.

As discussed at the beginning of this blog, many women enter the criminal justice system with trauma. This trauma is often the cause of many other mental health issues these women may have. As such, trauma often underlies the issues these women have. Many women may have experienced PTSD from sexual or physical abuse, pregnancy complications, neglect, child abuse or witnessing death. Many women may not know they have or are experiencing trauma. Therefore, I believe it is important to build mental health treatment and policies in prisons and jails that are trauma-informed. Not all women will require this level of care, but it is important for this type of care and treatment to be accessible to all, considering what we know about the profile of women entering into the system.

I believe it is important that all individuals who work with incarcerated women should be thoroughly trained to deal with individuals who suffer from mental health issues, and specifically trained on how women are affected. From the stories I have read, it seems as though facility staff often exacerbate women’s issues by incorrectly punishing inmates, i.e. sending them to self-isolation, or not truly understanding what it is that the woman needs. If all staff were trained, the relationship between staff and inmates may be improved, so that the experience of women in prisons and jails is more humane and allows for rehabilitation.

It is clear from the information I have outlined in this blog, that psychotropic drugs can be used in an unethical and inhumane manner. The deliberate drugging of incarcerated women by untrained non-medical staff, under the ruse that it is required medication, just so the individuals can be easily subdued, is barbaric. I believe there should be much stricter rules for the prescription of drugs, and that only a doctor can prescribe and administer them. Furthermore, I believe the use of these drugs before or during an inmates trial or court hearing should be banned unless absolutely necessary, as specified by a doctor.

As this blog shows, the reason why so many women enter the criminal justice system with untreated and or undiagnosed mental health problems is because access to mental health treatment is extremely difficult outside of the system, especially for low-income communities. Women who may not have had health-insurance or access to mental health treatment before entering jail or prison, may, for the first, be treated or diagnosed whilst incarcerated. It is important, therefore, to think about the lives that these women, particularly those from low-income communities, will be going back to after release. Where will these women access continued treatment? How? How does their diagnosis and treatment affect their lives with family members, especially children? How can they pay for their medication? And ensure they are able to take it correctly? Detailed, individualized re-entry programs should be set up or planned, with the individual’s input, from the moment of incarceration. It is all very well providing the best care for women inside jails and prisons, but it is almost pointless if all that work is unraveled the moment they are released.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the lack of appropriate mental health treatment within the criminal justice system may affect all inmates, but it disproportionately affects women from low-income backgrounds. As the population of women in prisons and jails continues to rise, policy makers and staff of correctional facilities should seriously take into account the needs of these women. If the mental health of these women is improved, it is more likely that their experience in the system will be more humane and foster an environment that allows for rehabilitation. What is the point of locking these women up, if there is no attempt to improve their behavior and ability to connect in a positive way with the outside world?

The unfortunate reality is that women from low-income communities are, in many ways, set up for failure. They have limited means of improving their standard of living or position in society, they likely lack the means of caring for their physical or mental health, and are statistically more likely to be involved in the criminal justice system than their high-income counterparts.

In this blog, I have identified the profile of women entering into the criminal justice system, explored the availability of mental health treatment in and out of the system, identified one controversial form of mental health treatment and proposed my own set of important points that should be focused on when creating mental health treatment plans. This blog is by no means an extensive or comprehensive work on mental health treatment for incarcerated women. The problem, like many other problems with healthcare in the US and the US criminal justice system, is too complex to be dealt with in one blog post. However, I hope this shows the reader how women from low-income backgrounds are disproportionately affected by mental health problems in prison, and sparks some interest for the reader to learn more.

Want to know more?

For further information on the issue of mental health treatment for Justice Involved people, please take a look at these sources:

For general information on mental health treatment in prison for all inmates: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/03/mental-heath-inmates

To see the Bureau of Justice Statistics on Mental Health in US prisons: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/press/imhprpji1112pr.cfm

More information on the use of psychotropic drugs in prisons: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/use-of-psychiatric-drugs-soars-in-california-jails/2018/05/08/57fcb9e2-52a0-11e8-a6d4-ca1d035642ce_story.html

For more information specifically on the prescribing of psychotropic drugs to justice involved women: http://jaapl.org/content/early/2019/09/13/JAAPL.003885-19

References:

- National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women Fact Sheet on Justice Involved Women in 2016.

- Jennifer M. Reingle Gonzalez and Nadine M. Connel, “Mental Health of Prisoners: Identifying Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Medication Continuity,” in Am J Public Health, 104, (December 2014): 2328-2333.

- Cynthia L. Blitz, Nancy Wolff, Kris Paap, “Availability of Behavioral Health Treatment for Women in Prison” in Psychiatric Services, 57, (March 2006): 356-360.

- Barbara Zaitzow, Psychotropic Control of Women Prisoners: The Perpetuation of Abuse of Imprisoned Women, in Justice Policy Journal, 7, (Fall 2010).

- Anthony Ryan Hatch and Kym Bradley, “Prisons Matter: Psychotropics and the Trope of Silence in Technocorrections” in Mattering: Feminism, Science and Materialism, (NYU Press, 2016).

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/income.html

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/03/690872394/most-inmates-with-mental-illness-still-wait-for-decent-care