Reproductive Justice is defined as the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, to have children, to not have children, and to parent children in safe and sustainable communities. Reproductive Justice is about access, as opposed to choice, for everyone, including the most marginalized people in our society. Reproductive Justice centers on the idea that our society cannot be free until its most vulnerable people are able to access the resources they need to live dignified lives. For the most marginalized women in our society, including those who are incarcerated, gaining access to health care is critical. Reproductive health care access would include contraception, abortion, comprehensive sex education resources, and adequate wages and support to raise a family. During and after incarceration, it is exceptionally difficult for many women to obtain this type of care.

I. Incarcerated Pregnancy and Childbirth

On any given day, there are more than 225,000 incarcerated women in the United States. Approximately 5% of women in jails, 4% of women in state prisons, and 3% of women in federal prisons are pregnant upon intake to the facility (5). Navigating the terrain of incarceration is already difficult enough for women, as criminal justice institutions have historically been built and operated for men (4). Currently, there are no mandatory standards for prenatal and pregnancy care for women in the American prison system! In the absence of clear policies mandating proper care and treatment, incarcerated women face many barriers to receiving adequate care while pregnant (5).

On any given day, there are more than 225,000 incarcerated women in the United States. Approximately 5% of women in jails, 4% of women in state prisons, and 3% of women in federal prisons are pregnant upon intake to the facility (5). Navigating the terrain of incarceration is already difficult enough for women, as criminal justice institutions have historically been built and operated for men (4). Currently, there are no mandatory standards for prenatal and pregnancy care for women in the American prison system! In the absence of clear policies mandating proper care and treatment, incarcerated women face many barriers to receiving adequate care while pregnant (5).

Most incarcerated pregnancies are deemed “high-risk” for adverse outcomes, including miscarriages, preterm labor, low-birth weight infants, and stillbirths. Some medical professionals have attributed these risks to poor health conditions of the mothers, many of whom were from disadvantaged socioeconomic communities with limited access to health care prior to incarceration (5). Many women enter incarcerated spaces with pre-existing health conditions. When combined with the inadequate health services administered inside prisons, the health of the mother and the unborn child can be severely compromised. In a nationally representative survey of women who had experienced a pregnancy during incarceration, 94% of women in state prisons and 48% of women in jails reported receiving an obstetric exam. Only 54% and 35%, respectively, reported receiving helpful counseling or support during their pregnancy (5). This demonstrates a disparity that exists in the quality of care offered by different types of correctional institutions. Regardless of institution type, most women expressed a desire to obtain more information about child care, prenatal exercises, and diet and medication restrictions to follow. This suggests that within these institutions, education for women on sustaining healthy pregnancies is severely lacking.

Additionally, it is difficult for incarcerated women to receive proper accommodations while pregnant. For example, medical authorization is required to sleep on a bottom bunk, which may be more comfortable for pregnant women, and mealtimes and food are set, presenting challenges to women with pregnancy induced nausea (5). Seemingly, these women have no control over their environment and the comforts of daily living during their pregnancies. It is also important to note that while incarcerated, women are both separated from their usual support networks and unsure of what will happen to their newborns after delivery. As a result, many women may find pregnancy to be extremely isolating and stressful.

Once these women are ready to give birth, they will typically be taken to a nearby hospital. However, too often, untrained correctional staff neglect or dismiss the symptoms of labor, resulting in many women being forced to give birth in their cells alone. With nearly no control over the environment they are giving birth in, most of these women will give birth under intense duress, increasing the likelihood for complications. For those who do make it to a hospital, it is unfortunately extremely common for laboring women to be shackled during delivery. Shackling can include handcuffs, leg irons, waist chains and other restraints. Not only do shackles increase the likelihood of placental abruption, potentially leading to a stillbirth, but shackles also limit the ability of medical staff to intervene in an emergency. Despite the risks, only 21 states have banned or limited shackling of laboring mothers during delivery (5). After a potentially traumatic birth experience, these women are typically separated from their newborns almost immediately after birth, and the newborn goes to a designated family member or into foster care. The mother returns to her correctional institution, potentially unsure if she will ever see her child again.

Many improvements must be made within the criminal justice health care system to allow incarcerated women to carry out safe and healthy pregnancies. Programs have been implemented in some facilities to care for pregnant women and their newborns in the short-term, but the system is still failing to address the underlying issues surrounding women’s incarceration and the family disruptions that result. One program is called the Prison Birth Project, where doulas donate their time and services to assist women in delivery, hoping to reduce the sense of isolation many women experience during birth. These programs have had great success, but unfortunately are not widely available and rely heavily on donations. In an attempt to create healthy mother-infant attachments, eight states have nursery programs inside incarcerated spaces that allow mothers to keep their infants with them for a designated amount of time after giving birth (5). However, these programs are sparse and widely criticized. Few states are equipped with proper community based alternatives for women and mothers in the criminal justice system. These alternatives should aim to allow women to serve out their sentences while maintaining family preservation. One of these programs, the JusticeHome program in New York City, allows women to complete home-based programs with their children and receive treatment for substance use and mental illness in order to prevent a future return to the criminal justice system.

References

- Alternatives to Incarceration. Women’s Prison Association, 2020, wpaonline.org. Accessed 21 April 2020.

- Prison Birth Project. RESIST, resist.org/grantees/prison-birth-project. Accessed 21 April 2020.

- Rovner, Josh. “Incarcerated Women and Girls.” The Sentencing Project. 20 June 2020

- Solinger, Rickie, et al. Interrupted Life : Experiences of Incarcerated Women in the United States, University of California Press, 2010.

- Sufrin, Carolyn, et al. “Reproductive Justice, Health Disparities, and Incarcerated Women in the United States.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol 47, No. 4, 2015.

II. Abortion

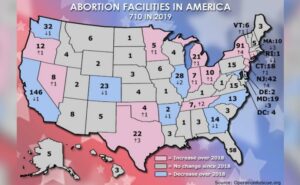

As a result of the United States Supreme Court’s landmark Roe v. Wade decision, a woman’s constitutional right to abortion has been guaranteed through the 14th amendment’s right to privacy. Although women both inside and outside of incarcerated spaces have the legal right to abortion, many women are left without the access to receive one. For example, abortion clinics are few and far between in the United States, as nearly 89% of U.S counties lack an abortion provider (3). Access to abortion can be financially onerous, as women must pay for extensive transportation costs and the cost of the procedure itself. Some states impose inconvenient waiting periods for women seeking abortion. These obstacles, in addition to the stigma and shame associated with terminating a pregnancy, deter many women from pursuing an abortion or seeking proper prenatal care.

It is not surprising that inside incarcerated spaces, the barriers women must overcome to receive an abortion are even more substantial. Once inside, the geographic, financial and regulatory barriers to women seeking abortion are greatly exacerbated. It is important to note that although these informal barriers continue to prevent incarcerated women from receiving an abortion, there are not necessarily any legal statutes barring access. In fact, courts have consistently recognized and upheld the right of an incarcerated woman to receive an abortion, citing that forcing a woman to continue with a pregnancy does not serve any penological interests (3). Over time, courts have also stuck down numerous obstacles put in the path of incarcerated women seeking an abortion. For example, courts have struck down the requirement that women obtain a court order from a judge authorizing transportation to an abortion clinic, and have held that correctional institutions cannot base abortion access on a woman’s ability to pay for the procedure and the transportation costs up front (3).

These major court decisions were helpful in removing some of the barriers that states sought to place in the path of incarcerated women, but were they enough to guarantee access to any woman who needed it? In a nationwide survey of correctional health care, groups of incarcerated women were asked about their perceived level of abortion access. Only 68% of women responded affirmatively to the question, “are women at your facility allowed to obtain an elective abortion if they request one?” Even more troubling, many incarcerated women are not aware that their constitutional rights were violated if they had been told to have an abortion they did not request, or told that they were not allowed to receive an abortion they have requested (2). This data suggests that correctional facilities, to an uncertain extent, refuse to allow abortion access despite the absence of any actual legal barriers. So, in many cases, the problem of access is not restrictive policies, but the lack of any clear policy at all. A study of state prisons has found that over ⅓ of institutions have no written abortion policy. Studies have found varying degrees of assistance with transportation, payment, and arranging the appointment (3).

Many prisons are located in rural areas, potentially hundreds of miles away from the nearest abortion clinic. More than half the 50 states impose waiting periods on women seeking abortion, which may require multiple trips to the clinic, a burden for women who have to rely on their correctional officers for transportation. It is important to note that, ultimately, incarcerated women are entirely dependent on their correctional officials for access to the care they need. In the absence of a clear policy mandating correctional officers to provide transportation, incarcerated women will face many barriers to the care they need. If correctional officers fail to act immediately after a request for an abortion is made, pregnancies continue to advance, potentially to a point where women may be forced to continue the pregnancy and deliver. In addition to finding a correctional officer willing to transport her, an incarcerated woman is often required to pay for both the transportation costs and the procedure itself. Given the lack of financial resources a woman can access from prison, many women are discouraged from or completely unable to receive the care they need.

Additionally, the American Public Health Association states that all women should have access to abortion counseling and services upon request. However, no institution is required by law to follow this standard. As many women are left to make this decision on their own, it is clear that access to counseling and support is severely lacking. For example, one incarcerated woman was informed that she was pregnant by the jail’s doctor, given a pamphlet, told to return to her cell, and given two hours to decide whether or not she would seek an abortion. She was not able to call her husband or family members (2).

In countless cases, incarcerated women are not granted their constitutional right to receive an abortion. This may have been due to an inability to pay, a lack of transportation, or waiting periods that allowed the pregnancy to continue until it could no longer be terminated. Some incarcerated women have sought restitution under the 8th amendment, citing that being forced to continue a pregnancy and deliver a child was cruel and unusual punishment. Thus far, only one court has held that when correctional officials delay or prevent a woman’s desired abortion, they not only violate the 14th amendment right to privacy, but also display indifference to a serious medical need, which violates the 8th amendment (3). This decision recognized the right to abortion as a right to healthcare, and declared that the state must cover the cost of the procedure for an incarcerated woman who cannot afford it. It also rejected the distinction between elective and medically necessary abortions (3). This decision was made by the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, and unfortunately applies to only three states. Thus, much more progress must be made in order to guarantee abortion access to all incarcerated women.

References

- Kasdan, Diana. “Abortion Access for Incarcerated Women: Are Correctional Health Practices in Conflict with Constitutional Standards?” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol 41, No. 1, 2009.

- Solinger, Rickie, et al. Interrupted Life : Experiences of Incarcerated Women in the United States, University of California Press, 2010.

- Sufrin, Carolyn, et al. “Reproductive Justice, Health Disparities, and Incarcerated Women in the United States.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol 47, No. 4, 2015.

III. Contraceptives and Coerced Sterilization

Most women in the American criminal justice system today are of reproductive age. More than 80% of these women have reported unintended or unwanted pregnancies in the past, either during or prior to their time spent in an incarcerated space (3). As a result, providing safe and accessible contraceptives to incarcerated women is a major tenet of reproductive justice. Unfortunately, access to contraceptives has historically been deemed non-essential care for women, despite the fact that between 60% – 77.9% of incarcerated women have expressed interest in starting birth control while incarcerated (3). Evidence suggests that when offered, incarcerated women do express interest in contraceptive services, but in most cases, there are significant barriers that must be overcome in order to receive them.

To explore incarcerated women’s attitudes toward contraceptive use and the level of access these women have to different birth control methods while incarcerated, the National Institute of Health interviewed women residing on Rikers Island (3). These women were of different ages, different races, and different communities and socioeconomic backgrounds. All but 1 of the 32 interviewed women agreed that Rikers Island, and all correctional institutions, should be providing contraceptive services to women. Not only did these women want access to the contraceptives themselves, but also sex education services and medical counseling prior to starting a birth control method (3). As every woman has unique contraceptive needs, it would be most beneficial to supply incarcerated women with all of the different contraceptive options, which should be administered in advance of release so that their bodies can adapt before returning home. A few of the interviewed women stated that providing contraceptives in incarcerated spaces could make a huge difference in the lives of incarcerated women after release, as many want to avoid pregnancy while finding employment and pursuing other goals after incarceration (3).

To explore incarcerated women’s attitudes toward contraceptive use and the level of access these women have to different birth control methods while incarcerated, the National Institute of Health interviewed women residing on Rikers Island (3). These women were of different ages, different races, and different communities and socioeconomic backgrounds. All but 1 of the 32 interviewed women agreed that Rikers Island, and all correctional institutions, should be providing contraceptive services to women. Not only did these women want access to the contraceptives themselves, but also sex education services and medical counseling prior to starting a birth control method (3). As every woman has unique contraceptive needs, it would be most beneficial to supply incarcerated women with all of the different contraceptive options, which should be administered in advance of release so that their bodies can adapt before returning home. A few of the interviewed women stated that providing contraceptives in incarcerated spaces could make a huge difference in the lives of incarcerated women after release, as many want to avoid pregnancy while finding employment and pursuing other goals after incarceration (3).

The most common reason that contraceptives are not widely available in incarcerated settings is cost. Many incarcerated women lack health insurance and are unable to front the cost of a contraceptive, and taxpayers have historically been hesitant to pay for the cost. Contraceptives are not always deemed to be “essential care” for women by the policymakers capable of supplying the funding. It should be noted that there is significant evidence to suggest that covering the cost of contraception increases the uptake and use by incarcerated women, reducing unintended pregnancies after release. A woman’s ability to leave incarceration with a reduced risk of an unintended pregnancy can actually reduce her risk of recidivism (2).

Even for those able to receive a contraceptive while incarcerated, barriers to receiving follow up care can negate many of the positive benefits of receiving the contraceptive. For example, women who experience side effects from a new birth control pill, or women who are unsure of how and when to have an IUD removed may not have the resources to find assistance, or feel comfortable engaging with the medical personnel inside the institution (3). Furthermore, there are some incarcerated women who may have access to a contraceptive method but choose not to use it. A major reason many incarcerated women do not pursue contraceptive use is due to a general mistrust of the prison health care system. Many incarcerated women who have received poor treatment and low-quality care in the past may feel concerned about the safety and efficacy of the contraceptives their institution has to offer. It is also common for incarcerated women to feel uncomfortable meeting with their institution’s health care provider for fear of being judged (3).

For women who are using a birth control method prior to incarceration, they are typically not allowed to continue using it once they enter a correctional facility. It can be harmful for a woman to abruptly stop using her preferred birth control method when she enters a prison or jail due to the side effects that could ensue. One facility in Utah is allowing women to bring their birth control pills into the facility with them upon intake and continue daily use. The financial burden is placed on the facility to continue re-supplying the pills. Much more work needs to be done nationwide, but this is a positive step towards giving incarcerated women the reproductive autonomy they are entitled to and minimizing disruption to their family planning goals (5).

While failing to address the contraceptive needs of incarcerated women, it must also be noted that the United States criminal justice system has a disturbing history of coerced sterilization inside of correctional facilities. It is not uncommon for incarcerated women to be offered reduced sentences in exchange for undergoing a sterilization procedure, typically tubal litigation for women (4). Clearly, the criminal justice system should have no authority to control the reproductive lives of incarcerated women, but widespread negative attitudes about individuals who have been convicted of a crime have allowed this to persist overtime. There is an underlying sense that eugenics is at play here, as “criminal” men and women who are deemed to be unfit to parent or pass on their genes are being coerced into sterilization (4).

Consent is at the center of this debate, because incarcerated women seemingly give their consent to a sterilization procedure by signing a form for their institution’s medical provider. However, it is important to note that with the promise of a reduced sentence and with coercion from correctional and medical staff, many women are not in a strong position to reject the procedure. Thus, consent is not given freely. Additionally, many of these women are not necessarily informed fully of the weight of a permanent sterilization procedure, and not given the proper education and support needed to make a fully informed decision (1). Without fully informed consent, the most basic reproductive and human rights of these women are being violated.

References

- “Contemporary Eugenics in US Prisons.” Rehumanize International. 23 Aug 2018. https://www.rehumanizeintl.org/post/contemporary-eugenics-in-us-prisons

- Janowiec, Callan FNP, “Implementation of Family Planning and Contraception for Female Inmates in Vermont.” College of Nursing and Health Sciences Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Project Publications. (2017).

- Schonberg, Dana et al. “What Women Want: A Qualitative Study of Contraception in Jail.” American Journal of Public Health Vol. 105, 11 (2015).

- Perry, David. “Our Long, Troubling History of Sterilizing the Incarcerated.” The Marshall Project. 26 July 2017.

- “Proposal would let Utah women stay on birth control in jail.” AP News. 18 Feb 2018.