Increased Spread and Decreased Awareness of Viral Infections within Female Incarcerated Populations

According to the CDC, human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States. It is

predicted that every sexually active person will be infected by HPV during their lifetime, if they are not properly vaccinated during adolescence and early adulthood. In addition, the CDC reports that hepatitis C (HCV) causes at least 17,000 deaths per year. Because incarcerated populations are exposed to risk factors, such as multiple sex partners or tobacco, their likelihood of developing STIs, including HPV and HCV, is increased. In addition, 74% of incarcerated women are between the ages 18 and 44, overlapping with the common age range of infection by HPV and HCV, showing why access to vaccines and routine screening are important factors in their healthcare (Sufrin, Kolbi- Molinas and Roth 2015).

Incarcerated women have higher rates of infection when compared to the general population , with HPV

, with HPV

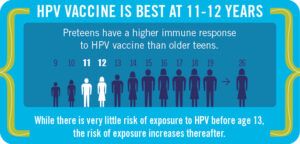

rates ranging from 27 to 46 percent (2). HPV is highly preventable; an HPV vaccine is offered to young adults to prevent illness over their lifespan and guidelines can be followed to decrease HCV risk. Because justice involved populations are less likely to have access to health care before entering an incarcerated space, access to preventative medicine is likely much lower. In combination with lack of resources about viral infections and increased likelihood of risky behaviors (3), justice involved women are disadvantaged. Additionally, poor treatment and lack of enforced screening opportunities, within the institution, results in higher rates of illness among incarcerated women.

In addition to higher rates of HPV among incarcerated women, studies have shown that Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women are significantly less informed about HPV and its vaccine than non-Hispanic white women (2). Levels of awareness among this group is extremely relevant, considering the racial profile of the US criminal justice system; it provides further reasoning behind why incarcerated women have higher rates of infection.

Beyond having higher rates of HPV and risk of cervical cancer, studies show that women in the U.S. criminal justice system have less knowledge regarding infection. Pankey and Ramaswamy found that only two-thirds of their sample reported understanding of HPV and its vaccine. Without access to information, women are less able to take preventative measures and alter behaviors to favor their health. In addition, participants in the study blamed incarceration for their inability to be vaccinated. Recurrent, short periods of time spent within institutions prevents fulfillment of the three-shot vaccination process.

Approximately one-fifth of incarcerated women are eligible to receive the HPV vaccination, based on CDC age recommendations (2). One clear improvement to health care would be implementing and enforcing opportunities for women to receive vaccines. Considering 90 percent of individuals leave the institution without health care, vaccines would help to maintain health while handling reentry. Additionally, 70 percent of justice involved women have children younger than 18 (2); families torn apart by the criminal justice system struggle for necessities beyond health care. If incarcerated mothers were able to vaccinate their kids, in addition to themselves, it would help to improve outcomes for the entire family, upon reentry.

Hepatitis C infections are also found at a higher rate among incarcerated populations (4); 69 percent of women tested positive to the HCV antibody (6). This can be partially explained by how HCV is spread. One method of developing HCV is by sharing needles and, as stated previously, 70 percent  of women are incarcerated because of nonviolent crimes, such as drug use (5). Additionally, behavior while incarcerated promotes the spread of HCV, such as tattooing or unprotected sexual acts (6). While treatment exists for HCV, it is rarely provided within the criminal justice system. Without proper mechanisms for regular screening and lack of recognition of symptoms, most women are not aware of their infection. Additionally, institutions do not always have the required specialists, such as a liver disease specialist, who would be able to adequately detect and treat patients (6). Finally, there is no method to release results to women who have reentered society, and because many women face shorter sentences, they are unable to attend follow-up appointments. These factors result in higher rates of prevalence and lower rates of treatment, a deadly combination.

of women are incarcerated because of nonviolent crimes, such as drug use (5). Additionally, behavior while incarcerated promotes the spread of HCV, such as tattooing or unprotected sexual acts (6). While treatment exists for HCV, it is rarely provided within the criminal justice system. Without proper mechanisms for regular screening and lack of recognition of symptoms, most women are not aware of their infection. Additionally, institutions do not always have the required specialists, such as a liver disease specialist, who would be able to adequately detect and treat patients (6). Finally, there is no method to release results to women who have reentered society, and because many women face shorter sentences, they are unable to attend follow-up appointments. These factors result in higher rates of prevalence and lower rates of treatment, a deadly combination.

However, creating policies that favor incarcerated women’s outcomes has many factors. Testing of women upon presentation of symptoms or high-risk behavior has resulted in many instances going unnoticed. Yet, enforcing universal screening erases the autonomy and privacy of women (1). Rather, a method of educating justice involved women and providing continuous opportunities for screening would allow for women to actively seek the care they deserve. STI prevention education could be provided in the form of reading material or programs offered and medical professionals hired should be competent at answering questions regarding procedures and results. If HPV is left untreated, it can promote cervical cancer and HCV leads to cirrhosis. It is essential for information and programs provide to women to include risks of untreated illness. In addition, medical examinations and preventative procedures must be explained, to indicate the importance of receiving regular healthcare. Implementation and enforcement of such policies will hopefully lead to better health outcomes for justice involved women.

Sources:

- Knittel, Andrea K. “Resolving Health Disparities for Women Involved in the Criminal Justice System.” North Carolina Medical Journal, vol. 80, no. 6, North Carolina Medical Journal, Nov. 2019, pp. 363–66. www.ncmedicaljournal.com, doi:10.18043/ncm.80.6.363.

- Pankey, Tyson, and Megha Ramaswamy. “Incarcerated Women’s HPV Awareness, Beliefs, and Experiences.” International Journal of Prisoner Health, vol. 11, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 49–58. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1108/IJPH-05-2014-0012.

- Solinger, Rickie. Interrupted Life: Experiences of Incarcerated Women in the United States. University of California Press, 2010.

-

Strickland, Justin C., et al. “Hepatitis C Antibody Reactivity among High-Risk Rural Women: Opportunities for Services and Treatment in the Criminal Justice System.” International Journal of Prisoner Health, vol. 14, no. 2, June 2018, pp. 89–100. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1108/IJPH-03-2017-0012.

- Sufrin, Carolyn, et al. “Reproductive Justice, Health Disparities And Incarcerated Women in the United States.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, vol. 47, no. 4, Dec. 2015, pp. 213–19. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1363/47e3115

- Zampino, Rosa, et al. “Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Prisoners: Epidemiology, Outcome and Treatment.” World Journal of Hepatology, vol. 7, no. 21, Sept. 2015, pp. 2323–30. PubMed Central, doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i21.2323.