Our Alsace-Lorraine Picture Postcard Collection

In developing my thesis with the history department here at Lafayette, I had the opportunity to work with a small collection of picture postcards from Alsace-Lorraine printed in the first half of the 1900s. Even though this collection was only one component of my much larger study of Alsace-Lorraine, it, in itself, proved to be a fascinating body of primary source material that would benefit from further research and lend itself to interesting new insights. In order to really explain the value of this collection, I think it is important to contextualize it within both the history of Alsace-Lorraine as well as the development of picture postcards as a visual medium.

Alsace-Lorraine is a small region that is today located in northeast France across the Rhine river from Germany. This, it turns out, is an ill-fated geographical position as the two provinces, Alsace and Lorraine, have been pulled back and forth between France and Germany throughout much of their history and, most notably, annexed and re-annexed four times in the less than one hundred year period from 1871 to 1945.

It was as a result of the Franco-Prussian War that on May 10, 1871 France was first forced to surrender Alsace and part of Lorraine to Germany. But, paradoxically, in losing physical control of the provinces, popular attachment to this otherwise little-known region began to grow within France. A myth of Alsace-Lorraine was born as the French, bemoaning their loss of the provinces, began to portray Alsace-Lorraine as the most patriotic region in all of France.

The two provinces were often depicted as young girls or twin sisters, dressed in traditional Alsatian clothing, waiting faithfully for the return of the French. This vision, which became so important to the French understanding of the region, was created in the political discourse at the time, fostered in schools, but also developed by the circulation of images of Alsace-Lorrainers in traditional costumes, frozen in an idyllic past.

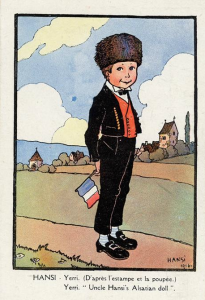

Some widely known examples of these images include Elle attend, a painting by Jean-Jacques Henner (left) or the drawings of well-known Alsatian cartoonist Hansi (right). However, one of the often-overlooked methods by which this vision of Alsace-Lorraine was mass disseminated is through picture-postcards.

Although, now, the picture postcard craze is largely forgotten, in the years prior to World War I picture postcards were produced in the millions and collected by people from all different social backgrounds, due in part to their initial popularity as souvenirs from the international exhibitions that were so popular in the 1880s and 1890s. Germany became the leading producer of picture postcards during the period and the rise in its production numbers from 314,296,000 cards in 1890 to 1,792,824,900 cards in 1913 indicates the growing popularity of the medium. Picture postcards became so popular in the 1880s and 1890s due, in part, to the fact that their visual imagery appealed to a broad swath of the population. Due to the cheapness of the cards and their postage, lower middle class and working class people could afford to buy and send them, while even middle class people avidly collected higher quality cards.

In the years leading up to World War I, before the camera was a mass-market item, professional photographers documented almost every aspect of life locally and nationally. However, as John Fraser notes in his article, Propaganda on the Picture Postcard, “The propaganda use of the picture postcard was realized very early on in the development of the postcard boom” and, as a result, photographers’ documentation of people, places, and events were often colored by nationalistic undertones. Many postcards, therefore, featured heads of state, soldiers, and nationalistic political caricatures of current events from within Europe as a means of appealing to people’s sense of patriotism. However, as much of the scholarship on postcards currently addresses, there was also a body of colonial picture postcards, which featured exotic and often racist images from Europe’s many colonies that also drew on nationalism in an effort to justify the colonial enterprise.

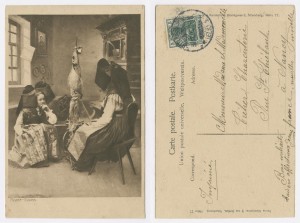

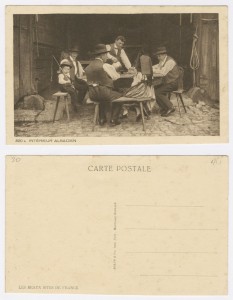

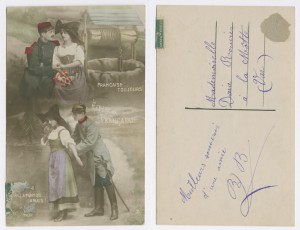

In analyzing this collection of 112 picture postcards featuring images of Alsace-Lorraine, an admittedly small sample, it appears that many of these same undercurrents associated with the discourse of both patriotism and imperialism are found. While not all of the postcards are explicitly nationalistic, all 112 cards depict Alsace-Lorrainer peasant women, children, or mixed groups (never men alone) in traditional costumes pictured with an idyllic and timeless rural simplicity. Some of the postcards simply feature a portrait of a woman in a traditional costume against a plain background (left), but, in the images that reveal more information, a “candid” view of peasant life in Alsace-Lorraine is shown (right), presented almost entirely during leisure time with their subjects occasionally holding tools but never working.

The postcards that are overtly nationalistic are only pro-French or anti-German, never pro-German or anti-French, suggesting that while the image of the peasant Alsace-Lorrainer in a traditional rural costume was recognized in both France and Germany, the French were the only ones who connected it back to their own sense of patriotism. Perhaps this is due in part to the fact that the French seemed to continually have a more visually consistent form of national iconography while the German nationalist symbolism was more obscure, drawing on many different historical periods. Most often, the nationalistic images on the Alsace-Lorrainer picture postcards visually suggest a maintained French loyalty that continues to thrive despite the German annexation of the region. Women are shown waiting and even praying for deliverance from Germany, and continually opt for France by physically pointing to signs for France or even romantically choosing a French soldier over his German counterpart; children are shown being taught French, and French symbols including French flags, red, white, and blue flowers, the tricolor cockette, and the French soldier or his helmet are found throughout the postcards. These nationalistic images seem to suggest that the timeless rural peasant and, therefore, the historical roots of Alsace-Lorraine, are decidedly French.

While the appeals to patriotism within the cards are largely explicit, they are accompanied by undertones of imperialistic paternalism. In an effort to meet consumer tastes, the picture postcards from Alsace-Lorraine build on the pervasive though misguided belief that the Alsace-Lorrainers peasants were simply patriotic Frenchmen who, unable to advocate on their own behalf, were forced to simply wait, against their will, to be saved by the French and delivered from German rule. It is not surprising, therefore, that the subjects on the postcards are almost entirely women and children, as this infantilization and feminization of the provinces only further reinforces their lack of agency. As Patricia Albers reminds us in her analysis of Native American picture postcards featuring the Ojibway people of Minnesota, “The problem with these kinds of photographs, of course, is not necessarily that they were contrived, but that most of those who viewed them were not aware of the deception.” Much like the Alsace-Lorrainers, the understanding of Albers’ Native Americans were, through picture postcards, manipulated in order to further reinforce the public perception of them as “noble savages,” a theme that also reappears in Paul Barclay’s analysis of picture postcards featuring Taiwanese indigenous warrior chiefs who were misguidedly glorified.

In the intervening fifty years before its re-annexation to France in 1918, these images of the Alsace-Lorrainer peasant began to contrast ever more sharply with the reality in the provinces, especially as the population of ethnic Germans increased, the economy began to improve, and a nationalization campaign by the German administration got underway. As historian Liard Boswell writes, “The seeds of future misunderstandings can be found in the paradoxical situation of a non-francophone and culturally distinct region being invested with a degree of patriotic symbolism on a scale known to no other French province.” With this assertion Boswell alludes to many of the conflicts between the Alsace-Lorrainers and the French administrations in the provinces that would color the history of the region from 1871 to 1945, including a systematic purge of Germans from the provinces by the French provisional government in 1918 as well as more minor tension resulting from disagreements over the construction of monuments and memorials in the region following World War I.

What is especially interesting, however, is the ways in which the Alsace-Lorrainers themselves chose to embrace even this misguided vision of their own French patriotism at watershed moments in their history. During the liberation of the region by French soldiers in November 1918, for example, the Alsace-Lorrainers chose to dress in traditional costumes like the ones pictured in these postcards, which were rare at the time, worn only in rural villages on festive occasions, and decorate the streets with French flags in order to present the arriving French with a vision of Alsace-Lorraine that matched these popular imaginings of the region. These celebrations thus suggest that the Alsace-Lorrainer peasant wasn’t entirely a construction of the French but was, to a certain extent, internalized by the Alsace-Lorrainers themselves as a vehicle to reinforce their sense of loyalty.

No sooner had the celebrations died down, however, than disillusionment set in. What had been forgotten in all of the excitement was that, in reality, this myth of Alsace-Lorraine was not true. The loyal, timeless, romanticized Alsatian peasant did not exist but was rather a construction that had become so real as to affect the French perception of the Alsace-Lorrainers and even the Alsace-Lorrainers’ perception of the French. As a result, even the French administration in the region after 1918 fundamentally misunderstood their Alsatian charges and were unable to adequately address the problems and sources of tension within the provinces.

Further study of these picture postcards and more like them is needed to make any definitive conclusions, but even the collection as it stands now offers valuable insight into the ways in which national identity was not only manipulated but also how this newly engineered nationality was mass disseminated through the media.

Further Reading:

Albers, Patricia and William James. “Images and Reality: Post Cards of Minnesota’s Ojibway People 1900-80.” Minnesota History 49.6 (1985): 229-40.

Barclay, Paul. “Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image-Making in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule.” Japanese Studies 30.1 (2010): 81-110.

Fischer, Christopher J. Alsace to the Alsatians?: Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939. New York: Berghahn, 2010.

Fraser, John. “Propaganda on the Picture Postcard.” Oxford Art Journal 3.2 (1980): 39-47.

Harvey, David Allen. Constructing Class and Nationality in Alsace, 1830-1945. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2001.

Leave a Reply