For the Fall 2021 semester, our group has been working in collaboration with Lower Hackett Farm (Hackett) to address a variety of issues identified by both our group and the director of Hackett, Miranda Wilcha. We consider an array of contexts surrounding Hackett, ranging from national scale issues like the growing local food movement to the hyper-specific conditions Hackett is operating under. From there, we devised four projects which we felt would have the greatest impact on the productivity of the farm and help Ms. Wilcha in her goal of creating a thriving community in Easton.

Background

For millennia, the growth and consumption of food has relied on the organized practice we call farming. This practice has evolved and been shaped by new environments, new social and political structures, and the exponential growth of our populations. For much of its history, farming, much like child-rearing or construction, took ‘a village’ in order to distribute food, seeds, and farming resources, and was practiced by the vast majority of a population which ensured the generally efficient and equitable distribution of these necessary resources. This can be seen by the fact that from Ancient Greece to the 19th century US, 80 – 90% of populations directly participated in agriculture (Waterhouse)(Migeotte, 2009).

It is only in the past century or so that our modern industrialized farming practices have consolidated food production and distribution into the hands of an ever-shrinking and aging labor force, aided by the growth of a mechanized one. This mechanization and automation has eliminated the need for a direct labor investment from much of the population. Particularly in the US, this consolidation has manifested in an inequitable distribution of food resources as evidenced by the 39.5 million Americans who live in supermarket redlined zones, areas where affordable and/or fresh food are largely inaccessible (USDA, 2019). As well, supermarket redlining tends to target minority Americans who live in these areas at a rate nearly six times that of white Americans (Dutko et al., 2012). With many beginning to recognize the systemic nature of how distribution affects different populations, farming practices are evolving once again to better serve the people.

Modern farming practices are primarily evolving through the adoption of older farming techniques and an increase in communally owned and operated farms. One might call this ‘evolution through reversion.’ Farms using minimal or no-tillage methods have increased over eight percent since 2012 (Dobberstein, 2019). No-till practices tend to be used by smaller, newer farmers aiming to counteract the negative impacts modern farming practices have on soil and climate health. No-till practices work with natural systems by building the soil microbiology and maintaining its structure, both of which tillage actively destroys.

One of the most direct ways farming is evolving to better serve people is through the proliferation of community gardens. The number of community gardens in the US has grown nearly sixty-six percent since 2012 (TPL, 2018). Essentially, community gardens are communal spaces where food is grown and distributed by community members for community members. For community gardens, labor, rather than capital, is the primary resource (though capital certainly continues to play a major role). Capital in a community garden context is necessary for acquiring an initial set of tools, the yearly purchasing of seeds, and other assorted expenses but it doesn’t compare to the millions spent on chemical fertilizers, soil conditioners, fuel, and equipment maintenance that larger farms use (USDA, 2019). Community gardens directly combat the supermarket redlining problem as “they’re a [direct] source of low-cost, healthy food in neighborhoods where grocery stores are too few and far between” (TPL, 2018).

Hackett Farm

Easton, PA, is a prime example of how community gardens are being used to resist supermarket redlining and inequitable food distribution. Easton is home to six community gardens dispersed throughout the city. Lower Hackett Farm specifically is the newest and the largest of the six, only having started significant development in 2019. Since it is the largest of the six community gardens, Hackett is where the city wants to spend the most time, money, and focus on optimizations. The farm is located on less than an acre of fenced-in plot about two miles away from the campus of Lafayette College. It is next to Fisk Field and located directly off of Wood Avenue. The aerial image from Google Earth of Lower Hackett Farm is shown below in Figure 1. Although the farm has grown and changed since this photo was taken, the perimeter of the farm is currently the same. The complete current layout of the farm will be shown as an AutoCAD drawing in Figure 3.

Fig 1. Lower Hackett Farm Aerial View

Image shows Lower Hackett Farm from an aerial perspective; with the road to the right. Inside, raised growing beds and in-ground beds take up most of the space. Though the picture is slightly outdated, most features remain the same. Source: Google Earth.

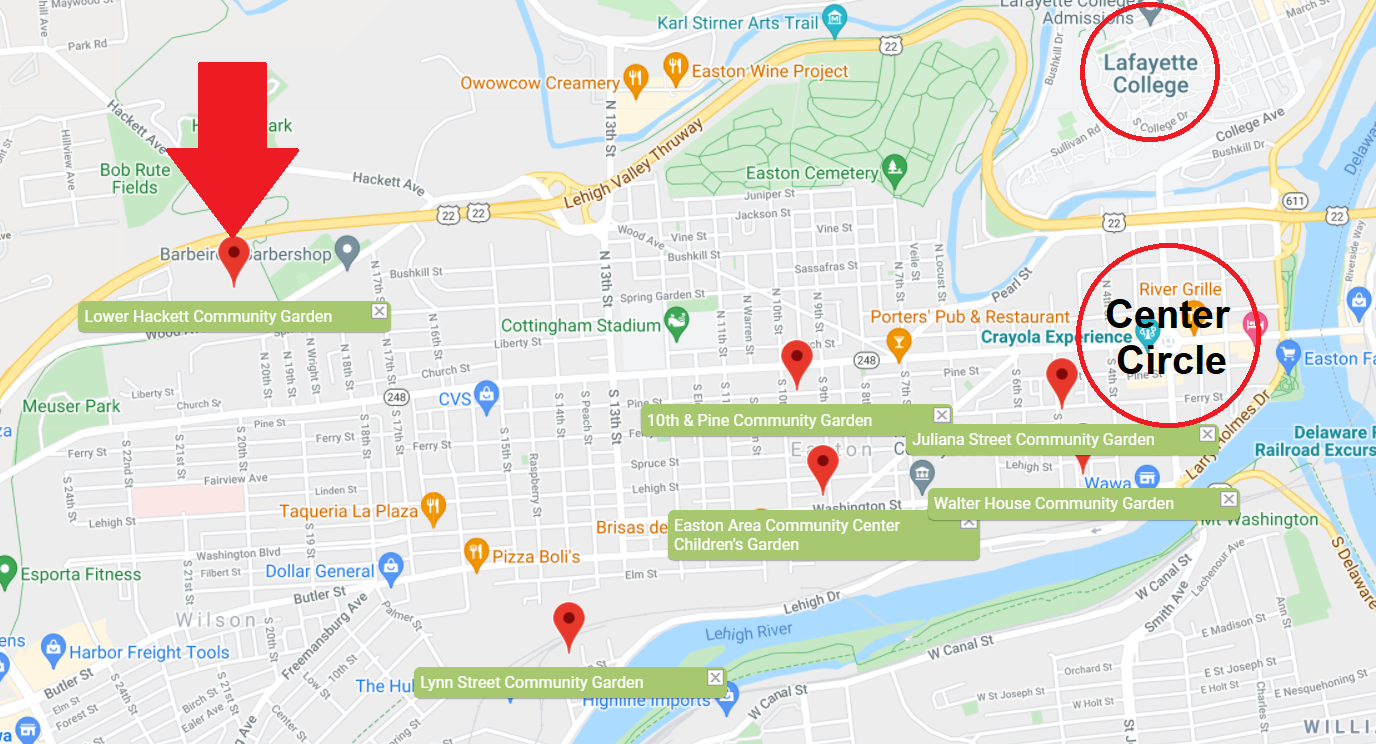

Fig 2. Map of Easton Community Gardens

Figure shows the location of the six community gardens throughout Easton. Lower Hackett Farm is indicated by the red arrow, on the western side of Easton. Lafayette College and Center Circle are also circled in red for context. Map Source: West Ward Community Initiative.

Figure 2 is a map that highlights the location of Hackett Farm within the greater Easton Area, highlighting other reference points (in red) such as Lafayette College, Easton Center Circle, and the other community gardens. It is important to understand how the location of the farm, being both within the West Ward and it being on the edge of Easton, affects the accessibility of the space in order to fully understand the socio-technical system we’re designing for. We must understand how its role as the hub farm shapes our socio-technical understanding of the Easton landscape in order to optimize the farm for it to have the greatest benefit to the community.

The overall goal of these community gardens and small urban farms is to “[provide] people with fresh fruits and vegetables”, “[give] residents the opportunity to maintain their own plots of green space”, and “[to foster] a community of individuals interested in sustainability and making Easton a greater city” (West Ward Community Initiative). Lower Hackett Farm is operated on land owned by the City of Easton but is managed by the Greater Easton Development Partnership (GEDP), which adopted all of Easton’s community gardens in 2018. The Greater Easton Development Project is a volunteer-driven, non-profit entity focused on Easton’s economic well-being, historical integrity, pragmatic development, vibrant culture, and urban hospitality. They developed Easton Garden Works as a branch of the GEDP that would manage and oversee all of the community gardens in Easton. Easton Garden Works uses these gardens to allow its residents to volunteer outside and enjoy communal green space.

After acquiring the fairly developed plot from the since-dissolved West Ward Neighborhood Partnership, the GEDP were limited in the changes they could make. In an effort to both maintain community-supported aspects and quickly expand and develop the community garden initiative, the Lower Hackett project proceeded with the intention of immediate returns on production rather than planned longevity. Irrigation planning, plot sizing and positioning, supporting infrastructure installment, and mapping of the space were unable to be developed as might have been desired with a new, ‘blank slate’ piece of land. Even with the lack of upfront planning, the farm has been effective in its goal of getting a foothold in the community. Hackett has been a productive farm and community space for two years, but there are still numerous ways in which the farm can grow and be improved to greatly benefit the Easton community.

Miranda Wilcha, the Community Garden and Compost Coordinator for the GEDP and sole full-time employee of the community gardens, was our primary contact informing our knowledge of the farm and its services and voiced some of her primary concerns. Some of these concerns included the efficiency and longevity of the space given its size, labor force, and how a general lack of cohesion and planning in the space is stunting its potential growth and production. Due to a reliance on volunteer labor, Ms. Wilcha is often overwhelmed with the wide variety of tasks and responsibilities that operating a farm requires. As a solution, Ms. Wilcha and our group believe that the space needs a significant overhaul with a thoughtful layout to its infrastructure and daily operations to reduce the amount of time spent on any specific task or responsibility. We all agreed that the appropriate first step would be to generate a to-scale model of the space to analyze how the space currently fits together and use it as a canvas to propose an alternative model. We went to Hackett Farm with a measuring wheel and took note of the general dimensions of the main sections of the farm and converted these dimensions into the AutoCAD drawing seen below.

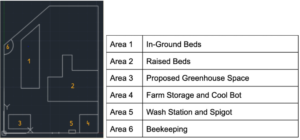

Fig 3. AutoCAD model of current farm layout

Figure shows the current layout of Lower Hackett Farm, with the adjoining table detailing the use for various sections of the farm.

Proposed Projects

Through our discussions with Ms. Wilcha, our group is targeting four main projects in our effort to overhaul and revitalize the space. Our report will provide a framework for how each of the projects should proceed with supporting socio-technical research. The first point that Ms. Wilcha emphasized is the need to design an in-depth map plotting the various additions and modifications. Much of her funding comes from the City of Easton, and the more detail provided supporting the need and usefulness of any modifications increases not only the probability of receiving funding but the speed at which the project may get approved. We must make the case to Dave Hopkins, the City’s Director of Public Works, that this project is worth funding and will be beneficial to the community. These plans could also be provided in grant proposals, one of the main ways the GEDP currently receives funding. Constructing a concise and in-depth plan is necessary for Ms. Wilcha to have a conceptual view of the whole farm and a definite proposed idea of what the space will look like for the future. She said that this will be the most important aspect of our project because this is what will have the greatest material effect on the progression of the farm. The remaining four projects are what will be within the plan. They are as follows:

- Redesign the vegetable wash station. When dealing with food, cleanliness and sanitation are of the utmost importance. There is currently a wash station that has done Ms. Wilcha well, but with the recent installation of a walk-in cooler on the premises which expands the kinds of crops which can be grown, there is a desire for a wash station to accommodate those new crops. This expansion would necessitate a high-pressure system as the primary washing source, and a soaking system for rinsing off various greens. This project was spearheaded by Konstantinos Voiklis.

- Expand and rearrange bed space within the farm to optimize the efficiency and the crop yield of the farm. As of now, many of the raised beds are relics from before Ms. Wilcha was involved with the farm, and their footprint occupies an unusual amount of space. Here, we will design a more optimal orientation with two main considerations. First, Ms. Wilcha would like a driveway running the length of the farm, from the door to the back fence wall. As of now, several beds are in the way. Second, Ms. Wilcha wants to expand the number of raised beds to accommodate additional community members. Optimizing their spacing and positioning for ease of maneuverability within the space will be primarily how that’s decided. This project was spearheaded by Steven Stillianos.

- Improve and add to the irrigation system. There is currently one spigot, and everything is watered by hand. We are proposing to add another spigot so that members of the community can use water for the community gardens without interfering with any of the attachments that others may be using. Also, this will make it easier to run drip tape to inground beds, saving lots of time wasted watering by hand and going to fill up the watering can every time that it runs out of water. This project was spearheaded by Casey McCollum.

- Write-up of a final plan proposal. The final part of this project includes creating one final plan that is drawn to scale to maximize the usage of space and to make the farm operate more efficiently. These plans will also be drawn to scale to ensure that the dimensions of the different appliances and workspaces are accurate, which not only helps with this project but can be referenced for future projects to properly plan out spatially where new features may go. This plan will also make it easier to visualize the changes we are proposing (since we have made a scale model of the current layout of the farm) and make the proposal make more sense by presenting multiple changes at the same time, which makes it more cohesive. This project was spearheaded by Casey McCollum.

As engineers, when designing and implementing any project, a variety of factors and contexts have to be considered if the project is to have an efficient and effective implementation and a long and sustainable lifespan. In this project, the considered contexts can be broken up into three main groups: socio-political, technical, and economic. Because the socio-political contexts exist outside of the specific projects, it will get its own section addressing the farm at large. The technical and economic contexts will be within the specific project section, as each project has different constraints and requires a unique approach.

Click here to go to our socio-political context page.