Introduction

Currently, there are many systemic barriers that discourage relations between Easton residents and the Lafayette community. Our main goal is to create a bridge between these two entities that establishes a broader sense of community encompassing students, faculty, staff, and Easton residents all of whom are disconnected despite living in such proximity on College Hill. To ensure that this project moves forward in a just and resilient manner, we are engaged with campus leaders and developed the groundwork for future groups to continue this project with direct community outreach. We hope that this proposal establishes a framework for a bridge design, but more importantly, establishes the vitality of considering all sociotechnical (interconnections between people and technology) systems in problem-solving (Lucena et al, 2010). The problem we hope to address with this proposal is the lack of connection and relationships between the Lafayette and Easton communities. This section will focus on analyzing the social aspects that should be considered to ensure that community is central to the design and considerations of this project proposal. In order to do this in a thoughtful and just way, we first gathered general information about the historic issues that often arise between college institutions and the cities in which they reside, otherwise known as town-gown relationships (Chenoweth). We then use this information to develop our research and understanding of the relationship between Lafayette and Easton. After discussing the historic trends of town-gown relationships that are directly tied to this Lafayette focused project, we will discuss the social impacts of the current connection between Lafayette and Easton that lacks accessibility, safety, and community engagement. Finally, we will address the previous proposals that attempted to address the poor connection and highlight the main takeaways from stakeholders that have helped us develop a more socially considerate and community-oriented design.

Figure 5: Williams Visual Arts Center

Lafayette College is built on a steep hill overlooking downtown Easton. For most of its lifespan, the school has existed entirely on this hill, maintaining its position overlooking the town. This changed in 2001, with the opening of the Williams Visual Arts Building, nestled at the bottom of the hill spanning over the Bushkill. This would mark the College’s first major foray into expansion down the hill and in the direction of Downtown Easton. As a prestigious, well-funded, and highly regarded liberal institution, Lafayette College is in a privileged position allowing it to overlook issues of elitism. The school’s continued expansion towards Cattell Street in the past few years with the McCartney Street housing project (see Figure 5) has been characterized by developing first and asking questions later, much to the chagrin of College Hill residents (Gaffney, 2017).

Figure 6: McCartney Street Dorms (Lafayette College, n.d.)

Elitism

Elitism has many connotations but in nearly all cases represents the reinforcement of oppression due to an imbalance of power. Institutions like Lafayette College tend to assume an authoritative status that may silence other ways of thinking by trying to enforce ideas of educated or well-established individuals like professors and administrators. In the Journal of Higher Education, the author Harold J. Harris notes this tendency when identifying that it is less productive to enforce the hierarchy of knowledge by forcing ideas and concepts on others from a place of power or expertise. It is far more productive to explain why an idea has come to fruition and its contextual importance (Harris, 1966, p. 457). Top-down relationships, like those traditionally found within a campus community, prevent the free flow of ideas between those that are in an authoritative position like faculty, administrators, and students. A focus on understanding the elitist tendency in college institutions and creating a more holistic approach to education and development is essential to productive solution seeking.

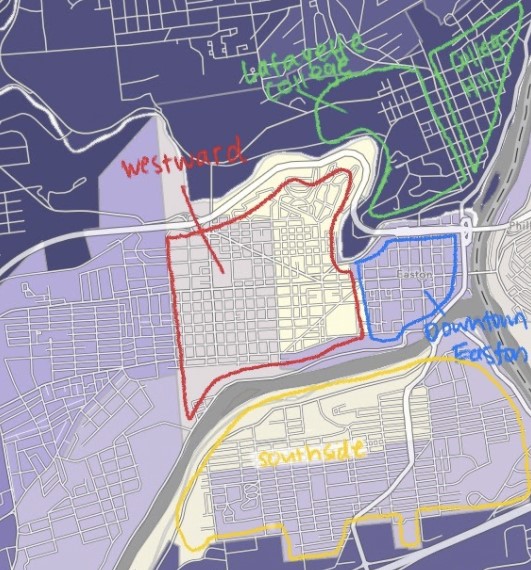

Elitism is not only found within a college institution, but perhaps more pronounced, between a college and the community in which it resides. This relationship is known as the town-gown relationship. Lafayette, both metaphorically and literally, positions itself above the Easton community, inhibiting an equitable flow of ideas, resources, and agency. This is especially true for members of the West Ward and Southside neighborhoods of Downtown Easton who face many injustices. These injustices stem from a long history of discrimination embedded in U.S. laws and regulations. This trend is known as systemic racism (Dove, n.d.). One of the most prominent forms of systemic racism that has continued to influence present day discrimination is known as redlining. Richard Rostein, the author of The Color of Law, examines redlining and its impact on the ways policy interacts with society. Rostein notes that “the Federal Housing Administration, which was established in 1934, furthered the segregation efforts by refusing to insure mortgages in and near African-American neighborhoods — a policy known as ‘redlining’” (Gross, 2017).

Redlining, or real estate redlining, was a method of ranking the loan worthiness of neighborhoods through color coded maps. Unsurprisingly, most of the red or unworthy/high risk neighborhoods were largely populated by black and other marginalized individuals (Jackson, 2021). White, upper-class individuals were of course bright green suggesting worthy of investment (Jackson, 2021). This method of segregation has continued to influence the geography and social impacts of neighborhoods today. Many of the same neighborhoods that were deemed red in the 1930s are today the ones who face countless environmental and social injustices including food deserts, concrete islands, placement of locally undesirable land uses (LULUs), lack of access to green space, less walkable and bikeable infrastructure, and lack of access to other basic resources. These trends are very prevalent in the city of Easton and can be witnessed by the stark differences in socioeconomic status (SES) of Lafayette College and College Hill versus the Downtown Easton, Westward, and Southside areas.

Figure 7 below identifies the clear geographical divide between communities that can be attributed to systemic racisms such as redlining. This image was taken from the ArcGIS database and shows the socioeconomic status (NSES Index) by Census Tract from 2011-2015 of the general Easton area (Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015, n.d.). SES is a useful tool in understanding the economic and social status of various areas as it considers “variables of educational attainment, income, housing, and employment variables or a composite of these variables” (David Wheeler et al., 2017). In Figure 7 below, areas that are colored in darker purple signify a higher SES status. The lighter purple and white areas mark a lower SES status.

Figure 7: Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015

More specifically, the Lafayette College area and the College Hill area have median household income and percent of households with income below the Federal Poverty Line of $78,018.0 and 5.9% respectively (Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015, n.d.). The West Ward area has a median household income and percent of households with income below the Federal Poverty Line of $25,645.0 and 37.5% respectively (Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015, n.d.). The Southside area has a median household income and percent of households with income below the Federal Poverty Line of $30,896.0 and 23.3% respectively (Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015, n.d.). Finally, the Downtown Easton area has a median household income and percent of households with income below the Federal Poverty Line of $21,845.0 and 32.9% respectively (Socioeconomic Status (NSES Index) by Census Tract, 2011-2015, n.d.). The above statistics highlight the disparities in economic well-being among members of the Easton community and how Lafayette College takes an elite position overlooking lower SES areas of Easton. In addition to the systematically oppressed neighborhoods of West Ward and Southside Easton, residents of Downtown Easton and College Hill have expressed concerns about Lafayette’s continued expansion into the surrounding areas (Gaffney, 2017). In any attempt to better connect the Lafayette community with the Easton community and improve town-gown relationships, one must first understand the political, social, and economic divides that prevent an equitable flow of resources, ideas, and impacts which can be witnessed at a simple level by Figure 7 and its associated statistics.

After gathering information and a preliminary understanding of these historic issues, solution seeking can be sought out by directly engaging with the communities to identify their needs and wants. The information gathered through this hands-on approach directly influenced the design considerations of the project. The subsequent sections outline the social, political, economic, and technical aspects of the problem we are trying to address through this project and offer some proposed solutions and considerations. While we were able to make a great deal of progress on this project in a short time, it is important to note that this proposal requires much more detailed research and community outreach going forward. Our team was careful to take the time to understand the many contexts of the issue first and to talk to faculty members that are well aware of the issues and some potential solutions to be considered. With that said, the following section goes into detail about how the lack of safe and accessible physical connections between Lafayette and Easton are directly related to the social disconnect between the two communities.

Physical Boundaries

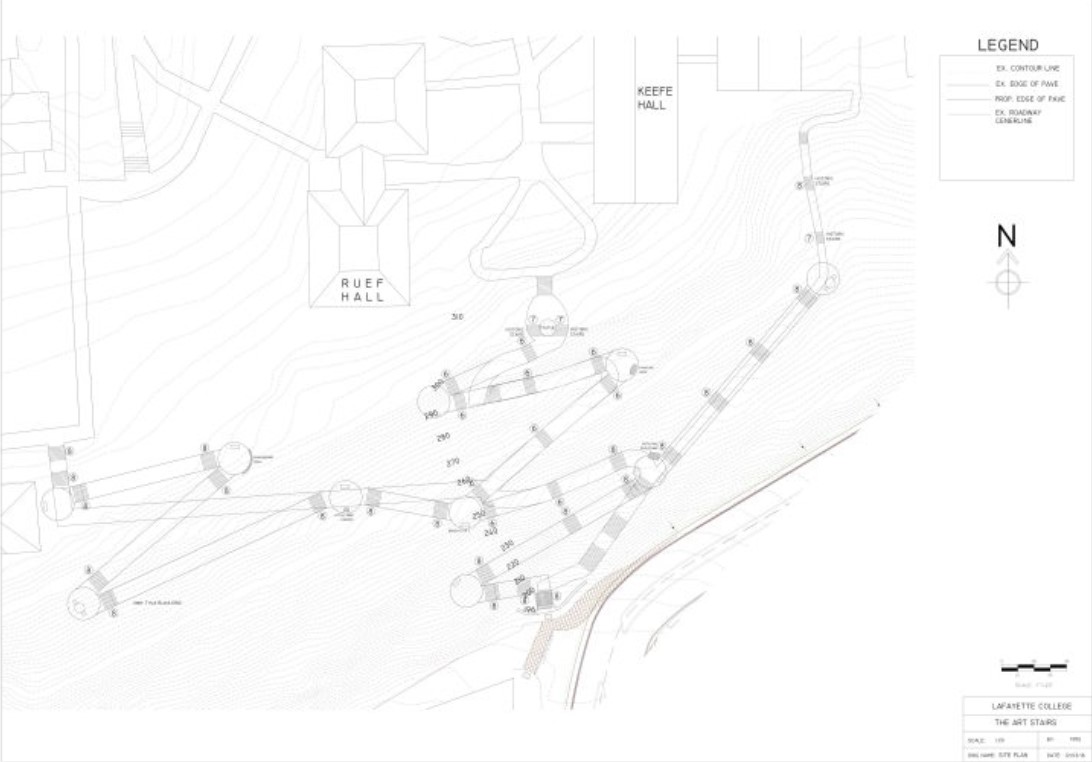

Getting down the hill from Lafayette’s campus to downtown Easton has always been difficult, with limited options available to pedestrians (Kelly, 2018). On the simplest level, it is tiresome to trek from the bottom of the hill to the top. This problem plagues both college students and college hill residents who wish to make their way downtown to enjoy the burgeoning restaurant scene and engage with the growing local economy. College Hill is a challenge on its own, but navigation issues are exacerbated by the extremely old and unkempt staircase cascading down the hill from between the Ruef and Keefe dormitories (as seen in Figure 8) as well as the dangerous trek that is College Ave.

Figure 8: Ruef and Keefe dormitories, as well as the old stairs leading down the hill

Figure 9: College Ave and McCartney Street Intersection. Note the sharp turn and lack of crosswalks.

Figure 10: Steep, unkempt stairs from College Hill to arts campus

Drivers are routinely speeding down the hill, and the tight curve from Cattell Street to College Ave gives drivers little to no time to react should a pedestrian cross the road from McCartney Street. Note in Figure 9 the lack of any crosswalk from the right side of College Ave to McCartney Street, as well as the sharp curve from Cattell Street into College Ave. Additionally, there is limited signage warning drivers of pedestrians or encouraging them to slow down. There are no speed bumps, speed cameras, or other forms of barriers to slow down cars, and the road is extremely wide, which has the tendency to cause drivers to drive above the posted speed limit (Speck, 2018). The school has done some work to make this road a bit more walkable, but there is still much to be done.

These physical barriers create social barriers in their wake. The arts campus has been cut off from the main campus, and feels “…notably empty,” according to students (Kelly, 2018). Students have difficulty getting to the arts campus, especially on snowy or rainy days. There are times where the stairs and sidewalks are not navigable, and the shuttle service is delayed as well, sometimes deep into the afternoon which unfairly prevents arts classes from meeting (Kelly, 2018). The stairs are of course only one part of the problem, with College Ave being incredibly dangerous to cross. One student, Noah Decker ‘19, was struck by a car in the area while crossing the street, fortunately he was not injured in the incident but there is a history of danger for pedestrians in the area (Kelly, 18).

We are not the first group to attempt to solve this issue of disconnection from the top of the hill to the bottom. There have been numerous projects in the past that have had limited success: A previous engineering studies proposal to revitalize the stairs through art (Gibbons et al, 2016), the infamous civil engineering glass elevator proposal (Figure 12), and the school’s work to help create safer walkways for pedestrians at the bottom of the hill (Sigafoos, 2021). Of these projects only the minor improvements to the walkways have been seen through. All of these designs were well intentioned but have ultimately failed in one way or another.

Each of these projects provides us with important context on how to approach our design and proposal. The arts stairs, while not coming to fruition, showed us the importance of incorporating art into public spaces, and helped us home in our research a bit more. We were able to look at other successes and see how art spaces can help to create public life in a place currently devoid of it (Grodach, 2009). Incorporating art into the design and into the accouterments of the bridge will be a fantastic way to involve both members of the Easton community and the Lafayette arts community. It is important to note that the final design must go beyond just introducing art to the area haphazardly, but with purpose and intent in order to truly create an improved public space (Grodach, 2009). Purposeful art is something that Professor Gil of Lafayette’s art department also emphasized to us in our meeting. He suggested that the bridge should not only include displays for student or locally created art, but also be as creative and interesting in its design as possible. The improvements to the sidewalks and pedestrian crossings in the area are a good start and help to align the arts campus with the main campus aesthetically. They certainly improve the walkability of the area, but they do not address the concerns of getting down the hill. They do provide us with a helpful aesthetic profile for what our solution could look like, however.

.

Figure 11: CAD Drawing of Arts Stairs Proposal (Gibbons et al, 2016)

Each of these projects provides us with important context on how to approach our design and proposal. The arts stairs, while not coming to fruition, showed us the importance of incorporating art into public spaces, and helped us hone in our research a bit more. We were able to look at other successes and see how art spaces can help to create public life in a place currently devoid of it (Grodach, 2009). Incorporating art into the design and into the accouterments of the bridge will be a fantastic way to involve both members of the Easton community and the Lafayetter arts community. It is important to note that the final design must go beyond just introducing art to the area haphazardly, but with purpose and intent in order to truly create an improved public space (Grodach, 2009). Purposeful art is something that Professor Gil of Lafayette’s art department also emphasized to us in our meeting. He suggested that the bridge should not only include displays for student or locally created art, but also be as creative and interesting in its design as possible. The improvements to the sidewalks and pedestrian crossings in the area are a good start, and help to align the arts campus with the main campus aesthetically. They certainly improve the walkability of the area, but they do not address the concerns of getting down the hill. They do provide us with a helpful aesthetic profile for what our solution could look like, however.

Community Perception

To avoid reinforcing college elitism, our team has carefully considered community perception in each aspect of the design. To do this, we have met with members of the college community to discuss how our project design can influence a more equitable and meaningful connection between the Lafayette and Easton communities. From our meetings with faculty members, we gained insight pertaining to the social context from Professor Wilford-Hunt and Professor Gil. Their feedback and the feedback from other community members in response to Lafayette expansion efforts will be elaborated on in the following paragraphs.

Figure 12: Proposed site of ‘Skyway’ Project (Tatu, 2018)

Discussions with Professor Wilford-Hunt provided insight about the plans and financial savings Lafayette has made for the area related to our project proposal. We discussed the 170-foot-tall glass elevator, more commonly known as the “Skyway,” that would carry up to 25 passengers from the intersection of Bushkill Drive and College Avenue (Tatu, 2018). All stakeholders, including the college and the Easton residents concluded that such a grand structure would be inappropriate in the context of its natural surroundings. Although it may be a very effective solution to getting people up and down College Hill, a giant elevator is merely a technical solution that does not take into consideration the needs of the community, the college, or the aesthetics of the area. According to Professor Wilford-Hunt, the elevator was designed entirely by an unnamed general contractor that was proposed to Lafayette College. This project, although technically sound, was designed without the input or consideration of any of the people involved in the community that would be directly impacted by its implementation. The college immediately turned down the proposal, showing that there is more to creating infrastructure than just building. This is an important lesson for us in our process. We must come up with a proposal that fits appropriately in the area as well as one that properly engages with the relevant communities who will be affected by it.

From Professor Nestor Gil, a sculpture professor at Lafayette, we learned that the Arts Campus is underdeveloped and underserved. Professor Gil pointed out that, “students arriv[e] late because of the shuttle […]. I have the experience of students not feeling as comfortable being in these buildings late at night as they would in buildings on the main campus because there aren’t as many full-time personnel on site” (Kelly, 2018). There is a distinct lack of personnel on site in this area, something that most students at Lafayette might not be familiar with due to this physical disconnection between campuses. As of 2018, Joe Swartcz was the lone custodian to take care of the buildings down the hill (Kelly, 2018). Whether it be during the day or late at night after a showing in the theater in Buck Hall, he was the only one to clean up after the place and keep things in order, which he described as taxing (Kelly, 2018).

The faculty experienced some similar issues. Technical Director Alex Owens routinely worked 60–80-hour weeks during the school year (Kelly, 2018). Owens had a wide range of responsibilities and spoke at length about how additional staff would greatly help to reduce his workload and grant him an improved work-life balance, as well as more time to spend with students rather than dealing with administrative tasks. The physical disconnection of the arts campus allows these issues to remain relatively unseen by the rest of the Lafayette community. Improving transportation and creating easier avenues to access these areas are key to helping the arts campus thrive at Lafayette. By bridging the gap between these campuses, we can better call attention to the needs of the arts campus and hopefully to the downtown community as a whole. By better integrating Lafayette with Easton, we will be able to strengthen the bond between the two communities and improve the quality of life for members of each community.

According to the English professor Suzanne Westfall, improved transportation options also require an attitude change. Professor Westfall notes that students at Lafayette, “…drive to the gym and drive to pick up their mail” (Kelly, 2018). Improving walkability and reducing the need for car traffic in the area can have a great positive impact on the area. Fewer cars will lead to a lower potential for injury and will make the area quieter and more inviting to pedestrian traffic. Increasing walkability has been found to help small businesses and communities by allowing for increased pedestrian traffic. Pedestrians are much more likely to stop into local businesses and engage with the community compared to those moving in cars, who tend to drive to one destination and then leave, rather than meander (Speck, 2018). When designing our bridge proposal, walkability was one of the key factors in our design. Building the bridge is all well and good but making sure that it is easy to use and functional for those who will be most closely affected by it is much more nuanced. Easton, and the greater Lehigh Valley area have experienced a tremendous economic revitalization over the last decade (Bresswein, 2019). Leaning into this growth and revitalization of what was once considered a dying rustbelt region is key to making this bridge something desirable for the community at large. Advertising and incentivizing use of the bridge when it first opens could be a way to bring a great deal of attention to it. This could be done in a variety of ways, from emails to art shows, and a whole host of other ways to positively engage with the affected communities.

Conclusion

As we discuss further in the conclusion of this report, we have primarily gathered feedback from the Lafayette community, however, as this project continues it is vital that the community is considered and effectively communicated with. To effectively communicate, project groups must listen to local community members (including those from the Southside and West Ward communities) feedback on the general framework of the project and use this feedback to adjust the design in an open-minded way. Surveys with open-ended questions can help to allow open communication between Lafayette project members and the Easton community.

More often than not, a college community and the surrounding urban community tend to work separately both in pursuit of their own wellbeing without considering the larger system they are a part of (Chenoweth, 2017). There is much evidence to suggest that improving town-gown relationships will be beneficial to both entities. Improving this relationship starts with recognizing the many ways these communities are interdependent. Some basic successes that could be found by working in unison and forming a stronger relationship include maximized capital and financial resources, attracting and retaining world-class talent, driving economic development, and elevating the level of both learning and life (Chenoweth, 2017).